World

100 years ago: Negro Leagues hold their first World Series

It lasted nearly three weeks. It was played in four cities. It was a best-of-nine series that went … 10 games.

Everything about the first Negro Leagues World Series — played 100 years ago — was ambitious, much like the leagues themselves.

The showdown between the Kansas City Monarchs of the Negro National League and the Darby, Pa.-based Hilldale Club (informally known as the Darby Daisies) of the Eastern Colored League featured five future Hall of Fame players and marked a major milestone in the evolution of the Negro Leagues and their place in baseball society.

“It’s a milestone that most baseball fans, I’m going to venture to guess, know very little, if anything, about,” says Negro Leagues Baseball Museum (NLBM) president Bob Kendrick. “That speaks to the value of a Negro Leagues Baseball Museum, because it’s important that we bring this to the forefront and understand the significance.”

At the privately funded NLBM, in the historic 18th & Vine jazz district of Kansas City, visitors this year have been treated to a special exhibit honoring the history of the Monarchs, on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of them winning the first of what was then known as the “Colored World Series.”

Even in Kansas City, many sports fans intimately familiar with the World Series titles for the Royals in 1985 and 2015 and the six total titles won by the Chiefs in the 1966 and 1969 seasons in the AFL and in the 1969, 2019, 2022 and 2023 seasons in the NFL might not realize the city’s first major sports championship occurred in the inaugural Negro Leagues World Series.

“It’s still the greatest professional sports franchise the city of Kansas City has ever seen,” Kendrick said of the Monarchs. “So, what a tremendous opportunity for us to highlight the occasion of that first World Series and honor the Monarchs and raise civic pride for those who call Kansas City home.”

But you don’t have to be a Kansas Citian to appreciate what Negro Leagues executives embarked upon way back in 1924.

Similar to the World Series held each fall between the American League and National League pennant winners, the battle for supremacy in the Negro Leagues World Series could only begin after some off-the-field squabbles were resolved.

The AL and NL had battled bitterly over players and business in the two seasons after the AL was formed in January 1901, but a 1902 Winter Meetings peace accord, in which both leagues agreed to honor each other’s contracts, allowed for the first “World Series,” as we now know it, in 1903. The inaugural event was a best-of-nine between the AL champion Boston Americans and NL champion Pittsburgh Pirates, in which Boston prevailed.

The initial Negro Leagues had hard fights of their own. The Negro National League was organized in 1920 by Chicago American Giants owner and manager Rube Foster, with eight teams competing among themselves to decide a champion. In 1923, Hilldale Club owner Ed Bolden, who had a reputation for signing players from other teams (including Foster’s), formed the Eastern Colored League.

Disputes between the two leagues prevented a Negro Leagues World Series from being held in 1923.

“Bolden and Foster didn’t necessarily care for one another,” Kendrick says with a laugh. “It was a bit of a strained relationship. Bolden felt Foster had misled him into thinking a team he had ownership of would be part of a Negro National League and, for whatever reason, Foster did not honor it. Also, from what I understand, he found a loophole and did not return Ed Bolden’s money.”

But at the conclusion of the 1924 season, Foster, Bolden and Monarchs owner J.W. Wilkinson settled their differences and determined sites and how to share the gate receipts for what would be the first Negro Leagues World Series.

Unlike the traditional World Series, which was (and of course still is) held exclusively at the home sites of the AL and NL champions, the plan for the Negro Leagues World Series was to not only visit the ballparks of the participants (Philadelphia’s National League Park and Kansas City’s Muehlebach Field) but to also visit two other venues (Baltimore’s Maryland Baseball Park, which was home of the Baltimore Black Sox, and Chicago’s Schorling Park, home of Foster’s American Giants).

“Part of that was getting access to stadiums and part of it was rewarding cities that had successful attendance through the year,” Kendrick explains. “It speaks to Rube Foster’s inventiveness. I’m not sure that was the best way to go for generating attendance, but it speaks to how forward-thinking Foster was.”

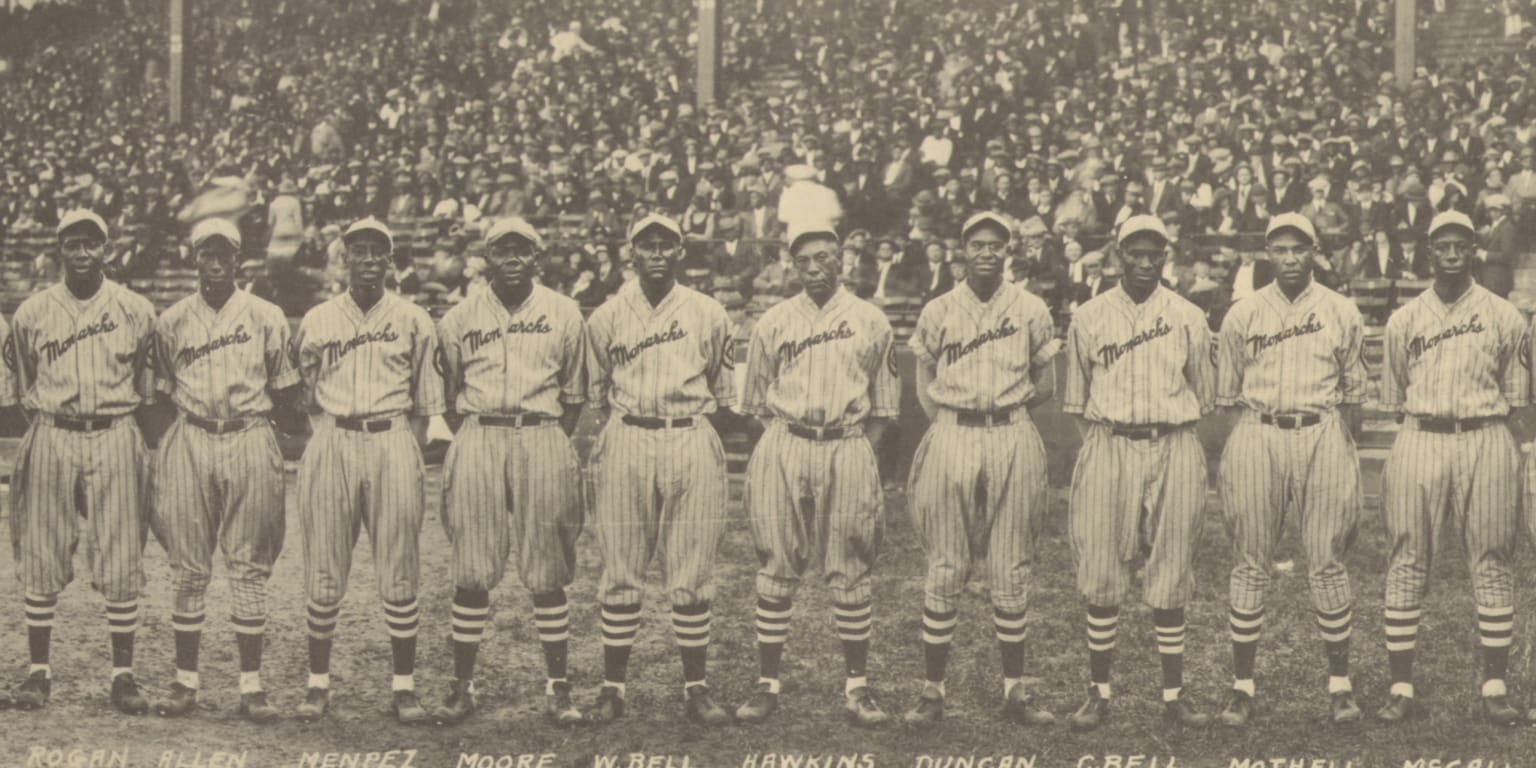

The Monarchs’ greatest strengths were their booming bats and their signature star — Wilber “Bullet Joe” Rogan, a pitcher/outfielder who was the league’s best all-round player.

“He is one of the most popular players in the game,” wrote the Call, Kansas City’s Black newspaper, “with a pleasing personality.”

The Monarchs had another future Hall of Famer in Cuban-born right-hander José Méndez, who served as player/manager.

Hilldale countered with a premier pitching staff that featured spitball connoisseur Phil Cockrell, Nip Winters, Red Ryan, Rube Currie and Script Lee. With that pitching and three future Hall of Famers on the roster in shortstop Biz Mackey, third baseman Judy Johnson and catcher Louis Santop, Hilldale was considered the favorite in the Black press.

But in Game 1, on Oct. 3 in Philly, the Monarchs took advantage of Cockrell’s three throwing errors and a terrific start from Rogan to win, 6-2.

Hilldale got revenge in Game 2, with Winters holding the Monarchs to four singles in an 11-0 shutout.

The series shifted to Baltimore, where, in Game 3, the two teams were tied, 6-6, after 13 innings. Darkness set in, and the game had to be called a draw.

Game 4, the following day, saw the Monarchs jump out to a 3-0 lead, but Currie came on in relief and stopped Kansas City in its tracks, allowing the Hilldale offense to tie the tilt and then win it with a run in the bottom of the ninth.

Those four games were played in four days. But four full days passed prior to the resumption of the series in Kansas City on Oct. 11. In the time between, the Kansas City Times, a white newspaper, did its part to spread the gospel of the burgeoning Black leagues.

“Let there be no dubious attitudes concerning the brand of baseball to be exhibited,” the paper wrote in the leadup to Game 5. “All the elements of big-league baseball will be present.”

Johnson’s three-run, inside-the-park homer in the ninth inning of Game 5 was the difference-maker in Hilldale’s 5-2 win, giving the Daisies a commanding 3-1-1 edge in the series.

But the Monarchs came roaring back. They grabbed one-run victories in Games 6 and 7, the latter of which lasted 12 innings. Then, after a three-day lull and a shift to Chicago, they earned another one-run win in Game 8, 3-2, by rallying for three runs in the ninth. Mackey, Johnson and Santop all made misplays that inning, and Frank Duncan’s single scored the tying and winning runs in a legendary game.

Hilldale avoided elimination with a 5-3 victory in Game 9. And that set up a decisive Game 10 in Chicago on Oct. 20, 17 days after the series had begun.

The 37-year-old Méndez, known as “El Diamonte Negro” or “The Black Diamond,” tapped himself as the starter for the Monarchs, even though he had arm surgery earlier in the year and a rested Rogan was at the ready. That bold decision paid off, as Méndez held Hilldale to three singles and one walk in a complete-game shutout, and the Monarchs scored five times in the eighth to win, 5-0.

“Sportswriters speak of Cy Young, Chief Bender, Mordecai Brown and others who had many ballgames behind them as super-athletes,” the Call wrote. “If they were super, what of José Méndez, who gets off an operating table to pitch a [three]-hit shutout on a cold day? And his years on this earth and on the ball diamonds exceeds theirs.”

Though this iteration of the Negro World Series would be held the next three years (Hilldale earned its revenge over the Monarchs in 1925, before the American Giants beat the Bacharach Giants in both 1926 and 1927), it was not the financial success the owners envisioned. It was not until 1942 that the Negro World Series returned, pitting the winners of the second Negro National League and the Negro American League against each other. That version of the Series lasted through 1948, at which point the quality of play in the Negro Leagues had begun to erode, post-integration in MLB.

The recent incorporation of the available Negro Leagues stats into the official MLB statistical record does not include statistics from the Negro Leagues World Series or other postseason play to be used alongside AL/NL postseason records.

Kendrick, a member of the Negro Leagues Statistical Review Committee, hopes that will change eventually.

“I don’t see any reason why not,” he says. “[Box scores from] those games are probably easier to track down than many of these games historians were successful in tracking down. There was a great deal more attention paid to postseason games. I think there would be an ample opportunity to have those stats included.”

For now, the 100th anniversary of the Monarchs’ triumph is good occasion to reflect on an event that attracted interest among baseball fans of all colors, further legitimizing the Negro Leagues at a vital stage in their development.