Fashion

Apodaca: Incident at Fashion Island raises specter of gun violence — again

It was another breezy, beautiful summer day at Fashion Island in Newport Beach. I strolled at a leisurely pace, enjoying the sunshine and the chance to feel normal again after a recent surgery.

My first stop was Whole Foods, where I used the Amazon return kiosk and purchased flowers and a card for a friend. I decided to see if there was a long line at the electric vehicle charging station.

There was, so I bought a cold drink and continued strolling while I checked out storefronts. When I finished my drink, I got in my car, intent on giving the charging station another try. But as I drove around to the charging area, I noticed something amiss.

A few cars were bolting from the parking lot, and some pedestrians were running. Two women waved their arms at me, and I rolled down my window. One of them blurted out words I’m not likely to forget.

“There’s a shooter. Don’t stop.”

Her kids were still inside the mall, she said, and she was trying to reach them on her cellphone. But in that frantic moment she still took a beat in order to warn a stranger— an act of kindness I’m also not likely to forget.

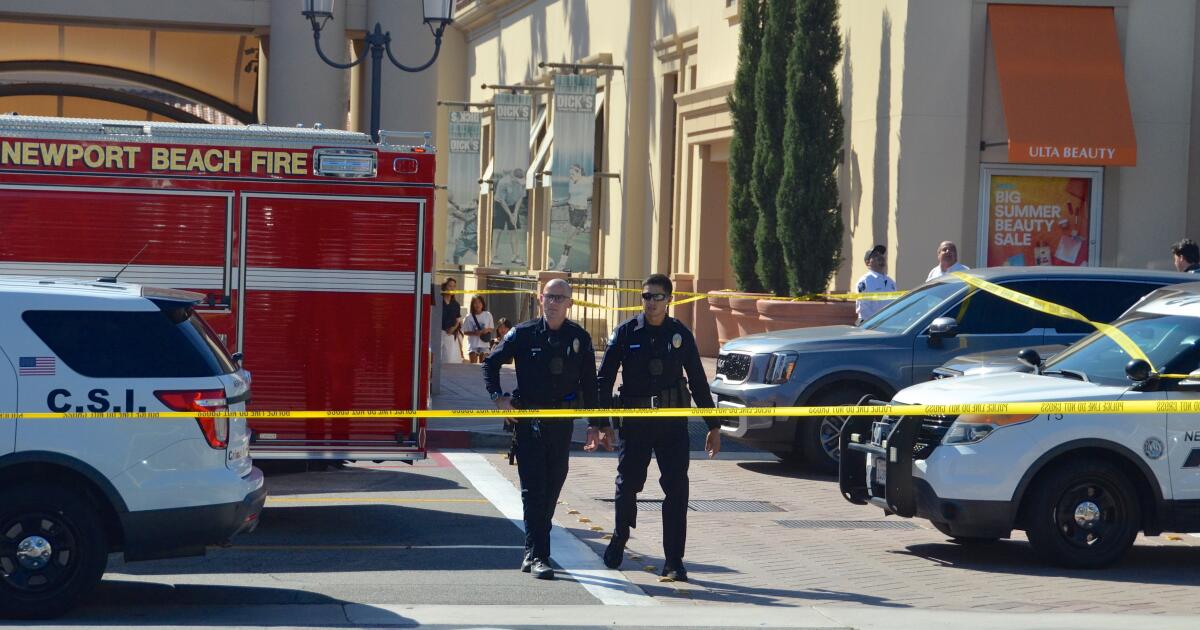

By now the tragic incident has been well-reported. Two men had attempted to rob a tourist couple from New Zealand near the Barnes & Noble bookstore. Shots were fired, but no one was struck. However, the woman died after being dragged and run over by a car driven by a third accomplice.

The three suspects were eventually taken into custody after law enforcement pursued them to Los Angeles County.

In the days since, I’ve had time to ponder these events. I had gone to the mall seeking normalcy. But the uncomfortable truth is that what occurred while I was there was normal. It has, for quite some time now, been commonplace for otherwise tranquil days to be interrupted by the threat of gun violence.

People fleeing in terror. Children in danger. Random, unnecessary killing. Sirens. Helicopters circling overhead. A high-speed car chase. Rumors and unfounded assumptions. Politicians hurtling accusations.

All of it — even the incongruous image of shoppers taking shelter next to yoga pants and protein smoothies — has become utterly, depressingly ordinary.

This is the world we have created, and the world we now live in — where schoolchildren routinely practice active shooter drills, where parents feel a gnawing dread whenever their kids are out of sight, and where lazy days at the mall can turn deadly in an instant.

It hasn’t escaped notice that the Fashion Island incident, as bad as it was, could have been so much worse. The shots that were fired missed. But far too often they have not.

According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, more than half of all Americans have experienced some exposure to firearm violence. In that light, it seems perfectly logical that nearly three-fourths of adults report feeling stressed about the possibility of a mass shooting, and one-third say that their fear of gun violence leads them to avoid certain places and events.

Sadly, though, when it comes to crimes involving firearms, we continue to argue and draw snap conclusions about what the “real” problem is. After the Fashion Island incident, some local elected officials were oh-so quick to point fingers at what they characterize as “soft on crime” policies coming from Sacramento and Los Angeles. On social media sites, postings ranged from the sorrowful to a near-hysterical rush to view the event as a sign that the dangers of the wider world are encroaching on what was once a peaceful suburban oasis.

The reality, however, is maddeningly complex and inadequately understood, and the data we do have can be difficult to analyze. Americans routinely identify crime as one of their top concerns, yet many are likely reacting on an emotional level while the information available is incomplete and often confusing.

We know, for instance, that the violent crime rate in California rose 3% last year compared with 2022, but the number of homicides declined significantly; the reasons why are still being studied.

We also know that the large majority of homicides are not committed by random strangers, but by someone the victim knows — a friend, acquaintance or family member. How do we better address this type of violence? What’s more, most gun deaths are suicides, which points us to a whole other set of questions and concerns.

A recent development could help provide a clearer picture. U.S. Surgeon General Dr. Vivek Murthy last month issued a landmark advisory declaring firearm violence to be a public health crisis.

This decision could have far-reaching effects because it frees the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to study gun violence and approach it as a treatable public health issue. This is the kind of common-sense measure we need.

I, too, felt a rush of anxiety when I heard the words: “There’s a shooter. Don’t stop.”

Fear is a powerful thing. It motivates us to run and hide when bullets fly. But it can also lead to misjudgments and missteps. At the very least, our response to violent crime should be based on accurate information, which is always the first step toward rational decision-making.