Jobs

Few Jobs. Poor Labour Productivity. And No Quick Fixes – Forbes India

There has been a pick-up in employment as manufacturing PMI improved in the past four to five months, particularly compared to the second half of 2023.

Image: Pradeep Gaur/Mint via Getty Images

Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman is likely to ring in the various positives which the economy has seen during the Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP) regime—at the upcoming Budget next week. It will include the sharp over-8 percent spike in GDP growth for FY24, year-on-year capex growth, a boost to digital payments and record foreign exchange reserves.

The call now will be for ‘Viksit Bharat’ or Developed India by 2047. For that to take shape, India needs to not just create more jobs, but also ensure that those with a practical set of skills get suitable employment. The need to boost employment, labour participation and skilling was an electoral challenge—and a sensitive matter—for the ruling government, which has been unsuccessful in creating more jobs and improving productivity of labour.

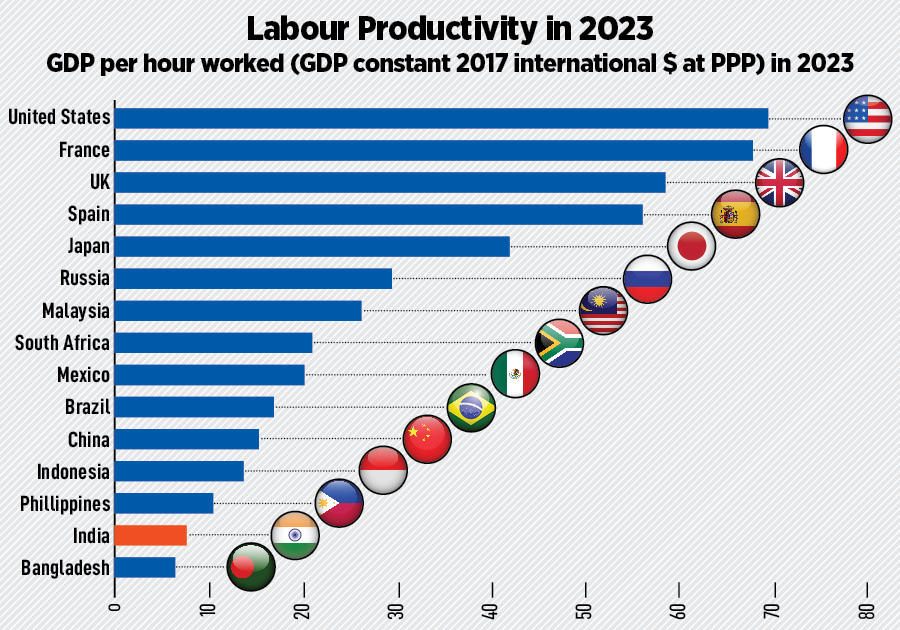

India is at a disappointing second lowest among 15 global economies in 2023, based on GDP per hour worked.

Sitharaman has been in discussions with industry lobby groups over the scope and opportunities for generative AI (artificial intelligence) in the job market. “The job requirements that are expected of new recruits are also changing. So, the people with old skillsets are now expected to have additional newer skillsets for entering into a certain area which till now did not exist,” Sitharaman had said in February, after she presented the Interim Budget for FY25.

But one should hope that India does not fall into the trap of creating pockets of skill and education through institutions such as IITs and IIMs in previous decades, and yet not being able to address near-term concerns of boosting jobs in manufacturing. “If we look at manufacturing, despite all the plans like Make in India and the China+1 strategy that are being talked about, the output growth in manufacturing is slow, relative to other sectors such as construction and infrastructure,” says Shreya Sodhani, regional economist at Barclays.

Abheek Barua, chief economist at HDFC Bank, says India has structural problems to deal with. “We are not looking at the average labour productivity for the economy but getting carried away by pockets of skill and getting industries to respond to the availability of skill as we saw in the information technology sector. We need to focus on traditionally labour-intensive sectors,” he tells Forbes India.

The problems in the labour market remains an issue, where we need a unified and accepted labour code to be adopted nationwide.

Blue collared jobs: Low Demand

The government may want the private sector to do the heavy lifting in creating more jobs in coming years. But when the pandemic receded, hiring of blue-collar jobs rose, particularly in the contact services which had broadly shut down during the pandemic. “A one-time boost and the rapid recovery likely pushed firms to go on a hiring spree in these sectors, leading to some slowdown following that. Sectors like construction are seeing low demand for blue-collared jobs in specific locations where the opportunities exist. This could be because of lower migration tendency in workers following the Covid-19 experience,” says Sodhani.

She assesses the output growth in manufacturing remains “low”—relative to other sectors such as construction and infrastructure—and this is despite plans like ‘Make in India’ and the China+1 strategy being drawn out. “With private investment yet to broad-base, private sector jobs in manufacturing were expected to be sluggish,” she says.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi on July 14 in Mumbai inaugurated Rs29,000 crore-worth of infrastructure projects, which he promised will help “someone get a job”. But government capex growth has not necessarily resulted in more jobs. “Construction has become equipment-intensive. The labour intensity of infrastructure has fallen quite a bit,” Barua says.

The Reserve Bank of India’s (RBI) KLEMS (capital, labour, energy, material and services) database—a systematic measure of factor productivity in India—shows that the growth rate of labour quality (measured by education attainment, earnings, etc) for the total economy has stagnated during the Modi rule at 0.3 percent (provisional) for FY24, compared to the same 0.3 percent in FY14, based on RBI’s July 2024 data.

There has been a pick-up in employment as manufacturing PMI improved in the past four to five months, particularly compared to the second half of 2023. Sodhani believes a pick-up in manufacturing through private investment, schemes like the Production-Linked Incentive (PLI) scheme, should definitely help jobs to pick up in the sector too, but a significant jump suddenly into next year will probably need more.

“One thing that could possibly help boost change, especially for private sector jobs, could be the implementation of the new labour laws that could potentially make it easier for private players to increase hiring more easily,” she says.

The fact is that barring the mobile phone scheme, the PLI schemes have not really worked. It means that the government has to do a rethink on existing schemes, and introduce new ones in the Budget. Whether PLIs should be sector-agnostic or if there’s a need for a bigger boost to exports (to generate jobs) are questions that need quick answers.

“The autos’ PLI is too focussed on EVs (electric vehicles), it can be made broader,” says HDFC Bank’s Barua. “We need an industrial policy which is guiding resources towards employment-intensive sectors,” he adds.

Also read: Joblessness and rising food prices: Real challenges for BJP and its allies

Now betting on GenAI

Besides a thrust to PLIs, the focus will be to create jobs from generative AI. “From the supply perspective, there should be no shortage of jobs in the AI space. From the demand side, the government will probably need to provide an environment for AI-related startups to mushroom as they will likely be private startups that will help generative AI make a base in India,” says Sodhani of Barclays.

“The ballooning number of global capability centers (GCCs) in India already shows how the simple back-office outsourcing has progressed up the value chain to research development and the next step from here would be generative AI,” she tells Forbes India.

Wadhwani AI, a non-profit institute which develops AI solutions for underserved communities in developing countries, has recently launched three new AI co-pilots to enhance the employability of youth and young adults across India. Genie.AI provides over 1,000 hours of skilling and entrepreneurship content, backed by a network of experts and mentors.

Barua says while the government’s focus on GenAI is the pivot which the IT sector needs to take, India is still not in the race to create GenAI jobs. “We could be a middle-tier supplier to AI. It may still not be the solution for job creation,” he says.

The lack of jobs raises the question of the efficacy of skill and vocational training in India. Often skills and training do not align with the demands of the industry, creating a skill mismatch and structural unemployment issues. “Internships and apprenticeship should be made mandatory along with private sector participation. These will help skilling, but also employability as per demand,” Sodhani says.

So, what is Sitharaman likely to announce in the Budget? A reference to GenAI is likely and so will the focus on jobs in manufacturing through PLI schemes, existing or new. There will be plans and intentions, but those may not get reflected in the budgetary numbers.