The space race between the United States and the former Soviet Union was in full acceleration mode during late 1950, cascading into the1960s. That two-country contest put extra oomph into NASA‘s resolve to fulfill President John Kennedy’s man-on-the-moon proclamation.

Relations between the United States and the Soviet Union were unmistakably edgy, a superpower rivalry fueled by differences in political ideology and economic pursuits, with both nations striving to influence the world by showcasing their technological and military prowess.

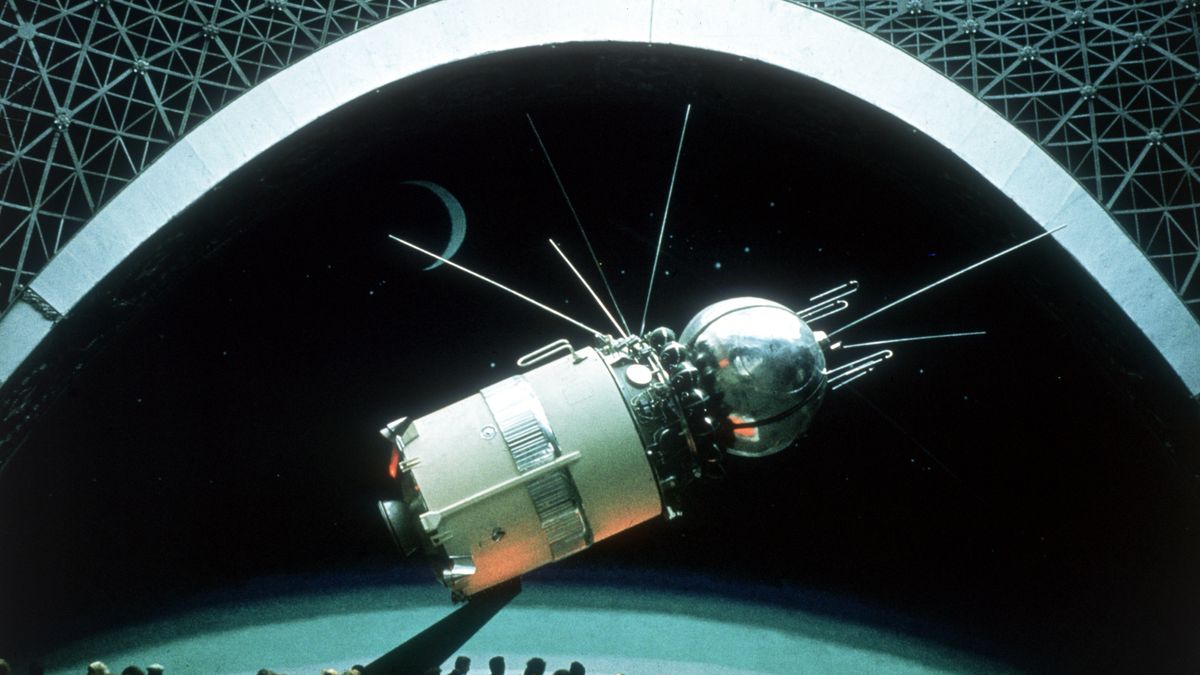

The Soviet Union was intent to crash a craft into the moon – and at the same time gain a political punch by delivering metallic pennants with the U.S.S.R.’s coat of arms onto the lunar surface. On September 13, 1959 the Soviet Union achieved that goal with Luna 2.

Techniques and technologies

To gain insight on how the Soviet Union built moon-bound gear, the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) carried out a covert spy job on a Soviet exhibit in 1959.

A CIA action team dismantled a “Lunik 2” exhibit to document what techniques and technologies were used by the Soviet Union.

Years later, that secretive act was detailed by the CIA and ballyhooed as a stealthy spy operation that was done unbeknownst to the Soviet Union.

The unusual overnight caper by the CIA involved Soviet upper stage space hardware that was being toted around as part of an exhibition to promote Soviet industrial and economic achievements.

Unrestricted access

Per a posting on the CIA’s “electronic reading room” site:

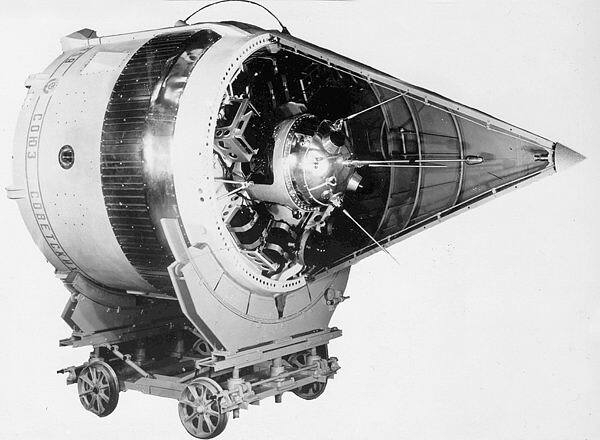

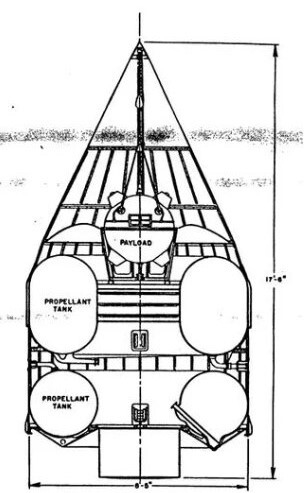

“A team of CIA officers gained unrestricted access to the display for 24 hours, which turned out not to be a replica but a fully-operational system comparable to the Lunik 2.”

The team disassembled the vehicle, the posting adds, “photographed all the parts without removing it from its crate before putting everything back in its place, gaining invaluable intelligence on its design and capabilities.”

Concludes the posting: “And the Soviets were none the wiser. Sound like something from a movie script? It really happened.”

Sanitized version

“The Kidnapping of the Lunik” was documented in a “sanitized” CIA historical review that was declassified and publicly posted in 1995. It was written by the CIA’s Sydney W. “Wes” Finer and published in the agency’s winter of 1967 edition of “Studies in Intelligence.”

It was eagle-eyed space historian Dwayne Day that first published a story in the mid-1990s on the CIA’s mission impossible-like tale in Quest, the informative History of Spaceflight Quarterly.

“I was the one who found the declassified document at the National Archives. It was in paper form. [The] document didn’t end up online until a decade or more later,” Day told Space.com. “Note that ‘Lunik’ is not a Russian word. This was an American slang term for Russian lunar missions, not what the Russians called them.”

Factory markings

More recently, in June 2020, John Greenewald, founder of the Black Vault, an archive of over two million pages obtained from the government by the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), published the document in a non-sanitized form that notes, as a subhead: “Getting factory markings from inside a Soviet upper-stage space vehicle.”

Those markings were later analyzed and detailed in a “Markings Center Brief” that revealed the probable identification of the producer of the Lunik stage and the fact that it was the fifth one made. Also fleshed out was identification of three electrical producers who supplied components, even the system for numbering parts, conceivably used for other Soviet space hardware.

Humpty Dumpty

The CIA Lunik skullduggery was not devoid of circumstances of comedic value.

Like Humpty Dumpty, trying to put things back together, then close up the crate was one of several high-jinx, high-stakes, but comical outcomes.

“The first job, re-securing the orb in its basket, proved to be the most ticklish and time consuming part of the whole night’s work,” notes the document. Indeed, the way the nose and engine compartments were designed prevented visual guidance to easily reassemble the space hardware.

“We spent almost an hour on this, one man in the cramped nose section trying to get the orb into precisely the right position and one in the engine compartment trying to engage the threads on the end of a rod he couldn’t see,” the document points out. “After a number of futile attempts and many anxious moments, the connection was finally made, and we all sighed with relief.”

As for the mission accomplished, kidnapping the Lunik was an “example of fine cooperation on a job between covert operators and essentially overt collectors,” the FOIA-obtained document states.

For more on this inside job, read the CIA’s historical review here.