World

Unequal exchange of labour in the world economy – Nature Communications

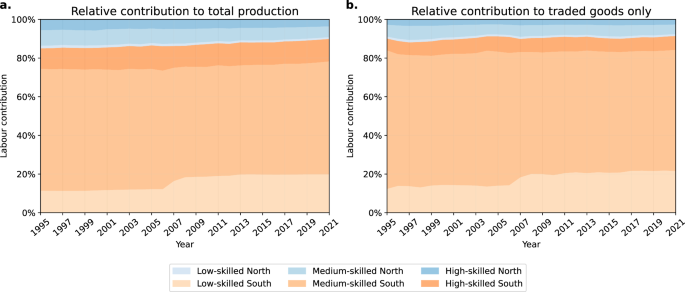

Contributions to global production

We find that, in 2021, the final year of data, 9.6 trillion hours of labour went into producing for the global economy. Of that, 90% was contributed by the global South (Fig. 1). The South contributed the majority of labour across all skill levels: 76% of all high-skilled labour, 91% of medium-skilled labour and 96% of low-skilled labour. In the same year, 2.1 trillion hours of labour went into the production of internationally traded goods (our use of ‘traded goods’ in this paper refers to both goods and services). The relative North–South contribution to the production of traded goods is similar to that of total production, with the South contributing 91% of all labour (73% of all high-skilled labour, 93% of medium-skilled labour, and 96% of low-skilled labour). Note the latter figures are underestimates, given that most global South countries are aggregated into regions in EXIOBASE (see Supplementary Table 1) and trade within these regions is not represented.

Blue indicates labour rendered by workers in the global North, while orange indicates labour rendered by workers in the global South. Skill levels are shaded from lighter (low-skilled) to darker (high-skilled). Panel a shows contributions to total production of all goods and services. Panel b shows contributions to production of traded goods and services only.

The South’s contribution to total global production has increased steadily over the period since 1995, across all skill categories. The largest increase has occurred in the high-skill category, with the South’s contribution to high-skill production increasing from 66% of the world’s total in 1995 (1.9x more than the North) to 76% in 2021 (3.2x more than the North). In fact, the South now contributes more high-skilled labour to the world economy (1124 billion hours in 2021) than all the high-, medium- and low-skilled labour contributions of the global North combined (971 billion hours in 2021). The South also contributes the overwhelming majority of labour across all aggregated sector groupings we derived from EXIOBASE, including agriculture (99%), mining (99%), manufacturing (93%), services (80%) and ‘other’ (89%). See Methods for sector aggregations.

Despite contributing 90–91% of the total labour that goes into global production and the production of traded goods in 2021, including the majority of high-skilled labour, the global South received less than half (44%) of global income, and Southern workers received only 21% of global income in that year. In other words, while global production is overwhelmingly performed in the global South, the yields are disproportionately captured in the global North, indicating a disproportionate command of the global product.

Table 1 shows that the total number of employed workers and total number of hours worked has increased in both the North and the South from 1995 to 2021, with the increase substantially larger in the global South. The final rows illustrate several interesting points. First, we see that workers in the global South consistently render more labour per worker than in the North, by large margins. In the final year of data, Southern workers worked on average 466 h more than their Northern counterparts (26% more). Second, we see that in the North, labour time per worker has decreased by 7% over the period, while in the South it has increased by 1%. To the extent that increased labour time has contributed to global economic growth over the past 25 years, this burden has been shouldered overwhelmingly by people in the global South.

Unequal exchange of labour

Our analysis confirms a substantial and persistent pattern of unequal exchange between the global North and South. In 2021, the global North imported 906 billion hours of embodied labour from the South while exporting only 80 billion hours in return (a ratio of 11:1). On average across the period, the North imported 15x more labour from the South than it exported in return. In other words, the North net-appropriates large quantities of labour from the South. This net appropriation occurs across all skill categories, including high-skilled labour. On average the North imports 4x more high-skilled labour from the South than it exports, together with 17x more medium-skilled labour and 29x more low-skilled labour. Figure 2 shows labour exports and imports by the global South across the period 1995–2021.

The unequal exchange of labour described above is not explained by sectoral differences. We found that the global North net-imports large quantities of labour from the South in all skill levels across all five sectors. On average, the North imported 120x more agricultural labour than it exported, 110x more mining labour, 11x more manufacturing labour, and 6x more service labour. In other words, it is not the case that the North net-imports labour in primary production from the South while net-exporting a smaller quantity of labour in secondary and tertiary production. On the contrary, the global North relies on a net appropriation of labour from the South across all sectors, including manufacturing and services. There is no sector in which the North net-exports labour to the South. This is demonstrated in Supplementary Fig. 1.

The time-series results demonstrate that the global South’s position deteriorated during 1995-2005, with the South–North exchange ratio increasing from 17:1 in 1995–97 to 21:1 in 2003–2005. During this period, which was characterised by draconian structural adjustment policies applied during the 80s and 90s, Southern economies were compelled to increase their exports of embodied labour by 24% simply in order to maintain the same quantity of imports from the North. The South’s position improved over the following decade (2005–2015), as the most aggressive adjustment policies were loosened and as the commodity boom took off, with the exchange ratio dropping to 10:1. This improvement was driven predominantly by an improvement in the position of China. However, improvements have ceased since 2015, and some regression has occurred.

Figures 3 and 4 show the total quantity of labour net-appropriated by the North over the period, by skill level and sector, respectively. The North net-appropriates labour across all skill levels and all sectors. It is worth noting that appropriation in the secondary and tertiary sectors (manufacturing and services) is now greater than in the primary sectors (agriculture and mining), and indeed this has been the case for most of the period covered.

Skill levels are shaded from lighter (low-skilled) to darker (high-skilled). These figures correspond to the net of imports and exports represented in Fig. 2.

The total net appropriation increased from 1995 to a peak in 2005 before declining during the decade 2005–2015. We find that the decline during 2005–2015 corresponds with an improvement in Southern wages against Northern wages. However, this improvement ceased in 2015 and wage ratios have stabilised (see section titled “Wage trends” below). The appropriation has increased in the years since, driven by an increase in the volume of trade. In 2021 the total quantity of net appropriation reached 826 billion hours. These figures are substantially larger than previous studies have found (see Supplementary Discussion 3 for details)25. Net flows from China to the North account for roughly one-sixth of total net South–North flows. It is worth noting here that the net South–North flow of embodied labour is not ‘paid for’ by an opposite net flow of embodied land, energy or materials (on the contrary, large net South–North flows occur across all input categories).

We find that this pattern of net appropriation plays a major role in the North’s consumption (Fig. 5). In any given year, the North consumes roughly twice as much labour as it renders, thanks to appropriation through unequal exchange. In 2021, net-appropriated labour comprised 46% of the North’s total consumption of labour. Figure 5 also shows that the economies of the global North have become increasingly reliant on low-skilled labour, the vast majority of which is net-appropriated from the global South (71% in 2021).

The dark grey bars represent labour net-appropriated from the global South (corresponding to the figures represented in Fig. 3). The light grey bars represent labour consumed in the North from all other sources: from the domestic workforce, from North-North trade, and from equal exchange with the South. Panel a shows Northern consumption of high-skilled labour. Panel b shows Northern consumption of medium-skilled labour. Panel c shows Northern consumption of low-skilled labour. Panel d shows Northern consumption of all labour (the sum of a–c).

While the majority of the North’s net appropriation of Southern labour is comprised of medium-skilled labour, the net appropriation of high-skilled labour nonetheless constitutes a significant feature of Northern economies. We find that global North economies net-appropriate more high-skilled labour from the global South (52 billion hours in 2021) than they obtain and consume through North–North trade (31 billion hours in 2021).

The wage value of appropriation through unequal exchange

As previous studies have pointed out15,21, because wages and prices are an artefact of bargaining power in the world economy (plus the level of commodification, the extent of monopoly concentration, etc.) as well as dynamics of supply and demand, it is not possible to assign a “true” monetary value to labour. The most we can do is to represent labour in terms of the prevailing wages experienced by different agents in the existing capitalist world economy, purely as a point of reference. Previous studies of unequal exchange, including by Samir Amin9, argue that the net appropriation of hidden labour from the global South should be represented in terms of the prevailing Northern wages; in other words, from the perspective of Northern workers and producers21. This is the approach we take here.

First, we established the scale of net-appropriated labour time within each skill level for each year. We then multiplied the net-appropriated labour time by the wages that Northern workers receive for the labour of the same skill level, rendered in the production of traded goods (ignoring goods produced for final domestic consumption). Labour is therefore compared like-for-like: for example, the appropriated quantity of low-skill labour is valued at the Northern wage for low-skill work, the appropriated quantity of high-skill labour is valued at the Northern wage for high-skill work, etc. In this way, we calculated the wage value of appropriated labour in a manner that answers longstanding questions about the degree to which this is affected by the skill level composition of exchange.

Our results show that in 2021 the wage value of labour net-appropriated from the South was worth €16.9 trillion, in constant 2005 EUR (Fig. 6). In other words, if Northern workers were to perform the net-appropriated quantity of labour domestically, it would cost €16.9 trillion in terms of wages (see Supplementary Discussion 1 for further interpretation). The time series shows that the wage value of the appropriation has more than doubled since 1995. Large increases occurred during the late 1990s, continuing an upward trajectory that began during the period of neoliberal structural adjustment in the 1980s (see evidence presented in previous work15). The appropriation plateaued from the early 2000s to 2015, and since then, has increased further. Over the period 1995–2021, the total wage value of net-appropriated labour sums to €310 trillion.

For robustness, we also calculated the wage value of net-appropriated labour using Northern wages for each skill level in the relevant sector (in other words, we valued the net-appropriated quantity of high-skill labour in the services sector at the Northern wage for high-skill work in the services sector, etc.). The results are only marginally lower, €14.2 trillion in 2021. The weakness of this approach is that it takes for granted large wage inequalities between sectors within the global North, even when correcting for skill, which are due in large part to extremely low wages in agriculture (as low as 2-3 euros per hour; see Supplementary Fig. 2). However, it is nonetheless useful to demonstrate that the large scale of the wage-value of net-appropriated labour cannot be explained by sectoral differences.

Wage trends

We find that the North–South wage gap is large and has been increasing over time for all skill level categories (Fig. 7). Here again, we assess labour involved in the production of traded goods only. Southern wages are 87–95% less than Northern wages at the same skill level, i.e. for equal work as defined by the ILO. Southern wages are 87% less for high-skill labour, 93% less for medium-skill labour, and 95% less for low-skill labour. The disparity is so extreme that high-skill labour in the global South receives 68% less than low-skill labour in the global North. Stated otherwise, for every hour of work at a given skill level, Northern workers are able to consume 8–19x more of the global product than Southern workers (8x more for high-skill labour, 14x more for medium-skill labour, and 19x more for low-skill labour).

Southern wage gains have not matched Northern wage gains in absolute terms. The average Southern wage has increased from €0.46 to €1.62 per hour (an increase of €1.16), while the average Northern wage has increased from €12.60 to €24.95 per hour (an increase of €12.35). Northern wages have increased 11x more than Southern wages. There is no “catch-up” occurring; on the contrary, it is a pattern of dramatic divergence.

These results indicate that workers in the global South, who receive an average €1.62 per hour, perform the vast majority (90%) of the labour that produces for the global economy, the vast majority (91%) of the labour that produces traded goods, and nearly half (46%) of the labour that supports growth and consumption in the global North (net of trade). The global economy is overwhelmingly characterised by a regime of cheap labour.

These wage gaps are not explained by sectoral differences. Our results show large and growing North–South wage gaps for all skill levels across all of the sectors we analysed. In agriculture, Southern wages are 85–91% lower than Northern wages for any given skill level. In mining, Southern wages are 93–98% lower. In manufacturing, 89–94% lower. In services, 83–90% lower (see Supplementary Fig. 2 for full results).

Despite growing wage gaps, there has been some reduction in the relative inequality between North and South. As of 2021, the average Southern wage was 94% lower than the average Northern wage, a small improvement from 96% in 1995 (Fig. 8). Improvements in the South’s position occurred during the period from 2005 to 2015. Improvements have since ceased and, to some extent, declined.

Labour’s share of GDP

We find that, globally, labour received, on average, 51.6% of world GDP during the 5-year period 2017–2021. In other words, only half of all value produced in the world economy (that is represented in prices and included in GDP accounts) is captured by workers in the form of wages. As Fig. 9 shows, this represents a decline from the late 1990s (1995–1999), when labour’s share of GDP averaged 54.7%. This suggests that labour’s position vis-à-vis capital has deteriorated over the period anlaysed.

Southern workers’ share of Southern GDP is notably lower than the global average, at an average of 47.5% during the 2017–2021 period, while Northern workers’ share of Northern GDP is higher, at an average of 54.7% during the same period. This indicates that the Southern working classes are weaker vis-à-vis national capital than the Northern working classes. In both cases, labour’s position has deteriorated since the late 1990s: by 1.3 percentage points in the South and 1.6 percentage points in the North.