World

World’s largest iceberg may be trapped in ocean vortex for years

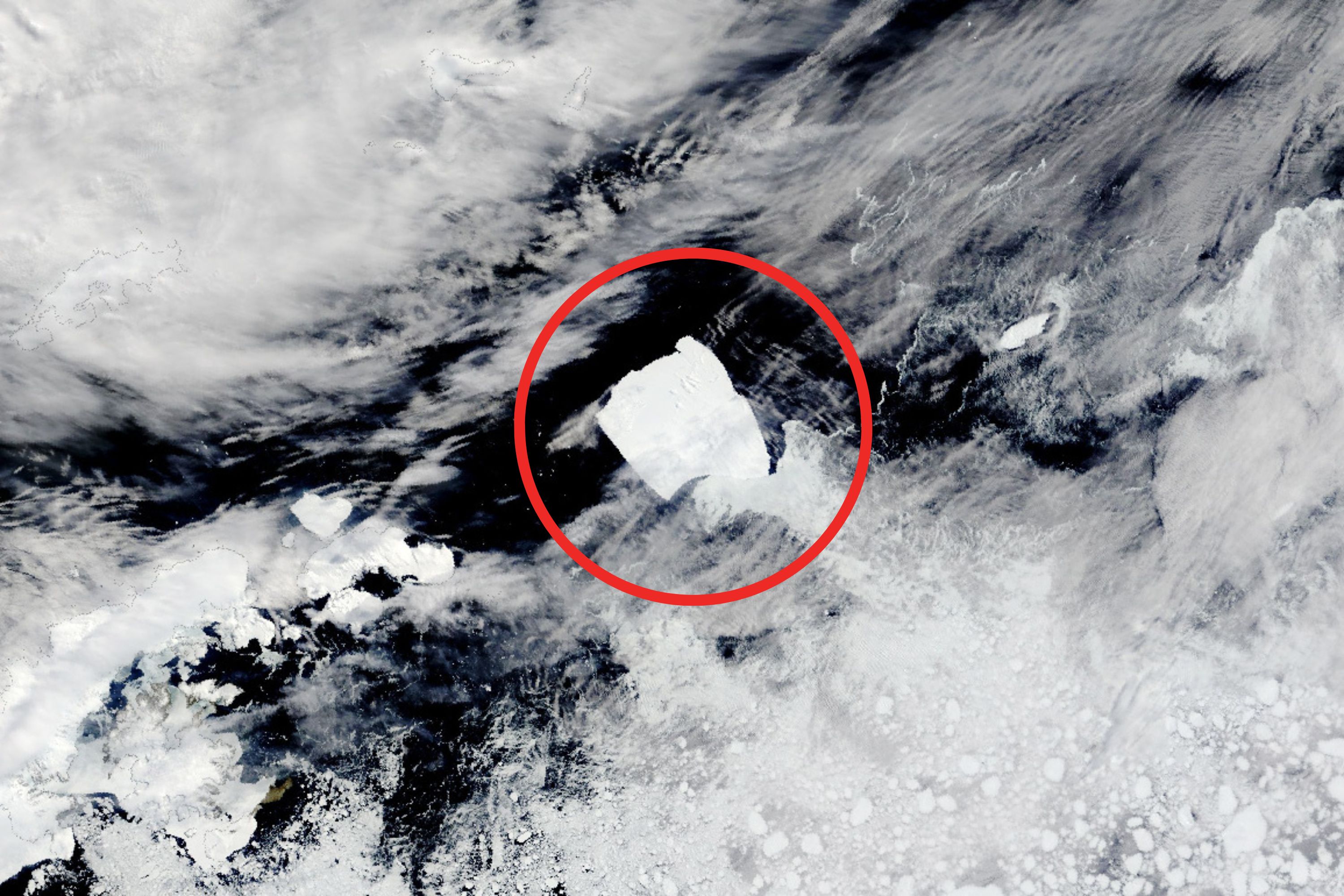

The biggest iceberg in the world has become trapped, traveling in a gigantic circle, and may be stuck there for years.

The iceberg, named A23a, is about 1,640 square miles in area, slightly larger than the state of Rhode Island and five times the size of New York City.

A23a calved off from Antarctica’s Filchner–Ronne Ice Shelf in 1986 but became stuck in the Weddell Sea for decades after grounding against the sea floor, only floating away from the frozen continent in 2020.

Now, instead of making its way into the warmer waters of the South Atlantic via the Antarctic Circumpolar Current, the iceberg has become trapped in a rotating current known as a Taylor Column. The iceberg is now located just north of the uninhabited South Orkney Islands, spinning anticlockwise by roughly 15 degrees a day.

Therefore, instead of slowly melting as expected, the demise of this gargantuan iceberg will be delayed until it leaves this Taylor Column—which, according to scientists, could be years from now.

NASA Earth Observatory images by Wanmei Liang, using MODIS data from NASA EOSDIS LANCE and GIBS/Worldview and data from the Antarctic Iceberg Tracking Database.

“A23a is the iceberg that just refuses to die,” Mark Brandon, a polar expert and professor at the Open University, told BBC News.

A Taylor column occurs when a fluid, such as ocean water, flows over a submerged object in a rotating system, like the Earth. In this case, the vortex is caused by a bump on the ocean floor called the Pirie Bank.

An obstacle like this can cause a current to split into two flows, generating a spinning vortex between the two above the obstacle. The iceberg has become trapped within this vortex, continuously circling.

“The ocean is full of surprises, and this dynamical feature is one of the cutest you’ll ever see,” Mike Meredith, a professor at the British Antarctic Survey, told the BBC.

“Taylor Columns can also form in the air; you see them in the movement of clouds above mountains. They can be just a few centimeters across in an experimental laboratory tank or absolutely enormous as in this case where the column has a giant iceberg slap-bang in the middle of it.”

NASA Earth Observatory images by Wanmei Liang, using MODIS data from NASA EOSDIS LANCE and GIBS/Worldview and data from the Antarctic Iceberg Tracking Database.

For now, A23a escapes the inevitable fate of icebergs that float away from Antarctica: melting.

Antarctica hit its lowest level of winter sea ice ever last year, with nearly 700,000 square miles less than the average.

“It was completely off the rails,” Ted Scambos, a senior researcher with the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences, said in a statement at the time.

Antarctica is losing ice at an accelerating pace, with the rate of sea ice loss increasing by a factor of 6 in the 30 years before 2020.

According to a study published in the journal Nature in 2018, Antarctica lost approximately 3 trillion metric tons of ice from 1992 to 2017. The rate of loss increased from about 76 billion metric tons per year before 2012 to 219 billion metric tons per year in recent years.

The melting of Antarctic ice contributes significantly to global sea level rise, with current estimates suggesting that Antarctic ice loss alone is responsible for about 0.4 millimeters of global sea level rise per year. If the West Antarctic Ice Sheet were to collapse completely, it could result in several meters of sea level rise, profoundly affecting coastal communities worldwide.

Sea levels rose by between 4 and 6 inches in the 1900s, and the rate of sea level rise is speeding up as we progress through the 21st century. A 2021 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Report forecast that we could see between 11 and 21 inches of sea level rise by 2100, but this increase could reach up to 6 feet under the worst-case scenario.

Do you have a tip on a science story that Newsweek should be covering? Do you have a question about Antarctica? Let us know via science@newsweek.com.