World

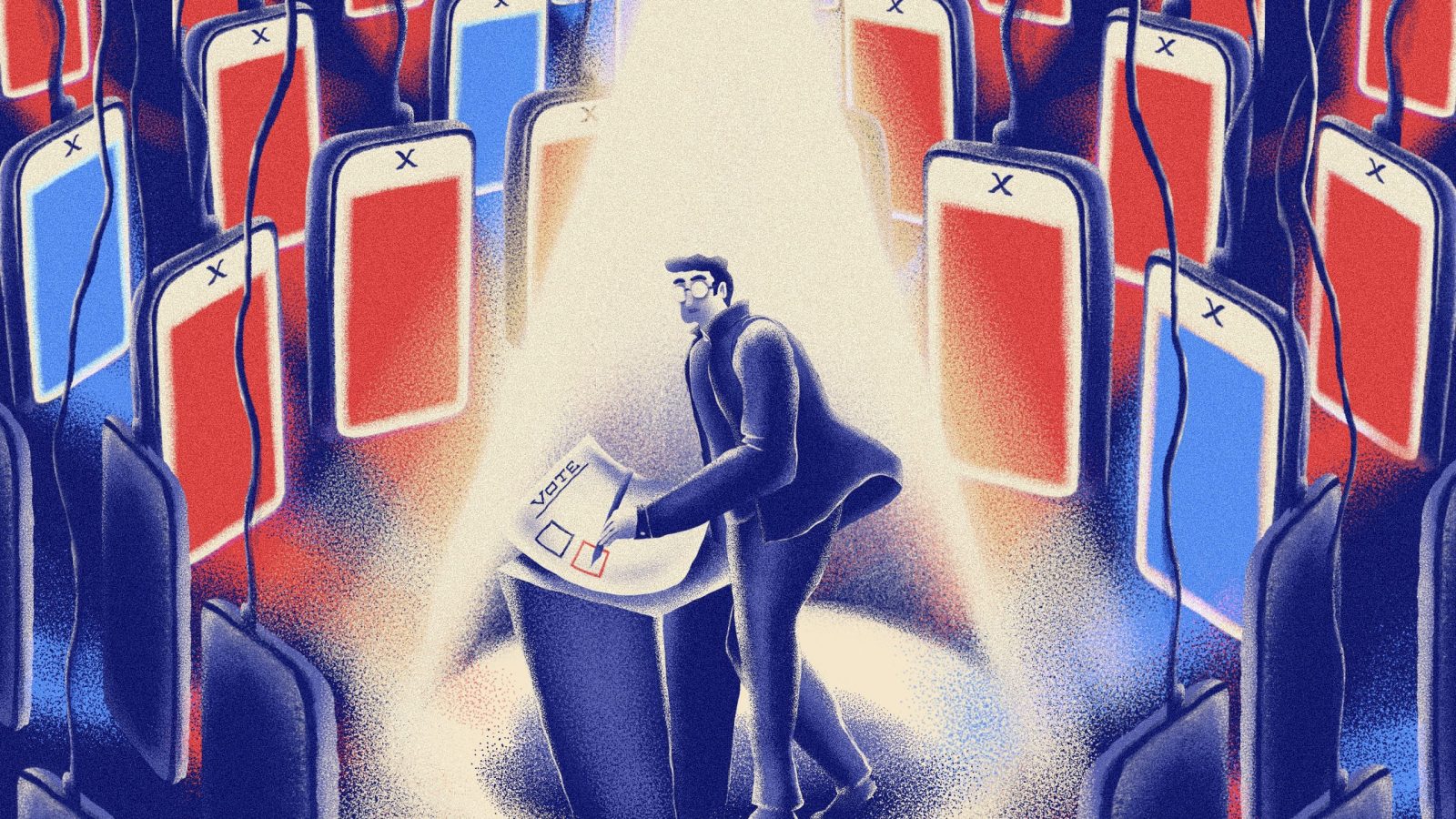

Elon Musk said he’d eliminate bots from X. Instead, election influence campaigns are running wild

As Rwanda prepared for its national election on July 15, something strange was happening on X. Hundreds of accounts appeared to be operating in unison, posting identical or oddly similar messages in support of incumbent president Paul Kagame. A team of researchers at Clemson University started tracking the seemingly automated network and discovered more than 460 accounts involved, sharing what appeared to be AI-generated messages.

“The campaign, which exhibits several markers of coordinated inauthentic behavior, seems to be trying to affect discourse about the performance of the Kagame regime,” the researchers wrote in a paper tracing the network.

It was the kind of revelation that would normally send moderators scrambling, particularly in the weeks before a national election. But when the group reported their findings to X, nothing happened. Flagged accounts remained up, and the network continued to post.

“There’s just no effort to take down any of this.”

It was a stunning result, given the sensitivity of the country’s election and how easy it would have been to stop the network in its tracks. “It’s obvious,” researcher Morgan Wack, who led the Clemson project, told Rest of World. “If you’re paying attention at all, it’s very clear you could take down several of these accounts. There’s just no effort to take down any of this.”

Wack’s experience is part of a larger shift in moderation on X, which has opened the door to influence operations around the world. In the two years since Elon Musk took ownership of the company, its trust and safety team has been decimated — and the result has been a steady drip of networks like the one uncovered in Rwanda. Simply finding the networks is harder than ever, as researchers must do without API access and face growing legal risks after their work is published.

As X has pulled back from fighting influence operations, the stakes for democracies have only grown. Eighty-two countries will see elections at some point in 2024, including giants like India, South Africa, and Mexico, as well as smaller nations like Rwanda and Sri Lanka that are easily overlooked by moderators. X doesn’t wield influence in all of those countries, but in places where it does, the platform’s indifference to moderation has left democracy alarmingly vulnerable.

Organizations that monitor for influence operations globally have already cataloged several other ongoing campaigns, mostly focused on regions where X remains influential. In only the past six months, the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab) has registered influence campaigns aimed at discrediting Georgian protestors and spreading confusion around the death of an Egyptian economist — both powered by inauthentic X accounts. Chinese-language spambots have continued to flood sensitive search terms on X, effectively suppressing and harassing dissident Chinese groups on the platform.

For Wack, the biggest concern is how many other campaigns are going undiscovered. With so many elections happening around the world, countries with less global attention or less well-known languages are likely to fall through the cracks.

“If you’re doing this in Tagalog in the Philippines, I’m never going to see it,” he said. “There’s not the attention that would give researchers the opportunity to even come across it.”

No social media platform is completely immune to influence campaigns, but researchers say the uptick on X is noticeably higher. According to DFRLab’s managing director, Andy Carvin, much of the change can be traced to specific decisions the platform made under Musk’s leadership, particularly laying off 80% of the platform’s trust and safety team. “If you look at X circa 2024 and compare it to where it was during the U.S. election in 2020, the trust and safety team that was once there is gone,” Carvin told Rest of World.

Another change was the rebuilding of X’s verification system, initially intended to highlight verified, notable accounts with a “blue check” badge. Musk revamped the system, making the badges available to anyone paying a subscription fee — claiming that the need to pay a fee served as verification that the user was a human, not a bot. Instead, the easy availability of the badge has made a verified status on the platform far more accessible to coordinated campaigns.

“It is shocking how easy it has been to find accounts that appear to be bots spreading division around the U.K. vote.”

The result has been a flood of new campaigns targeting elections. Starting in May, researchers at the human rights group Global Witness monitored election hashtags leading up to the U.K. election on July 4. More than 610,000 of the posts were from a network of “bot-like accounts” that promoted conspiracy theories, xenophobia, and other divisive topics.

Like the Clemson researchers, Global Witness informed X of their findings, but received only an automated reply. The accounts remain live on the platform, where they have shifted to spreading misinformation about the U.S. election or anti-migrant protests in Ireland.

“It is shocking how easy it has been to find accounts that appear to be bots spreading division around the U.K. vote, and then to watch them jump straight into political discussions in the U.S.,” Ellen Judson, the group’s senior investigator of digital threats, told Rest of World.

When Musk first moved to acquire X, he emphasized the dire effects of bot accounts, and pledged to remove them as one of his first acts as owner. He appeared to be following through on that promise in April when he announced a “system purge of bots & trolls.” (Later that day, the platform’s official safety account described the purge as “a significant, proactive initiative to eliminate accounts that violate our Rules against platform manipulation and spam.”) But the fruits of those efforts have been slow to ripen, and both spam and sock-puppet accounts remain common on the platform.

When researchers have succeeded in removing bot networks, it has largely been the result of legal force. In July, the U.S. Department of Justice took action against 968 X accounts alleged to be part of a Russian disinformation campaign. The platform voluntarily suspended the accounts, but only after a court-ordered search and more than a month of filings and procedure.

Renee DiResta, former research manager at the Stanford Internet Observatory, told Rest of World many of the informal mechanisms for taking down influence campaigns are now closed off.

“There have always been efforts to interfere in the politics of their geopolitical rivals.”

“In prior times, Twitter’s integrity teams would engage with people outside of the company, and there would be more proactive ways of doing investigations and responding,” DiResta said. “I don’t think the platform has very much interest in engaging in that way now.”

Researchers are also facing growing impediments to finding influence operations in the first place. The easiest way to access X posts at scale is through the platform’s API, making it vital for researchers and academics. But while API access was once available for free to academics and research groups, it’s now metered according to access tiers that can cost as much as $42,000 a month.

Under Musk, the company has also sued research groups for reporting on activity that reflects poorly on the platform, launching civil cases against the Center for Countering Digital Hate and Media Matters. The former case has been dismissed, but the latter is scheduled for trial in April 2025. The lawsuits have had a chilling effect on the community at large, making many groups reluctant to conduct research on the platform.

But while there’s less interest in tracking down the operations, there’s no indication that the operations themselves have slowed down — a fact with chilling implications for the remaining elections of 2024. Dozens of elections will stir up dozens of different national feuds, and wherever platforms fail to police inauthentic activity, influence operations will take advantage.

“There have always been efforts to interfere in the politics of their geopolitical rivals,” DiResta said. “We saw this in every prior media ecosystem going back centuries. It’s done on social media now because people are on social media. So of course they’re going to continue to do it. And why wouldn’t they? There’s no downside.”

.jpg)