World

Earthquake Kids grateful their Little League World Series run 30 years ago provided hope

Twelve-year-old Spencer Gordon was having a sleepover with his best friend, Jared, in his Northridge home on Jan. 17, 1994, when he was woken up by what he could only describe as an unrelenting boom.

“Deafening,” Gordon recalls now, 30 years later. “You couldn’t hear your own scream.”

Gordon saw Jared being flung across his bedroom as it shook, ricocheting off the walls. He tried to run away, but couldn’t find his footing as the seismic force kept knocking him down. His mirror and dresser both fell in front of his door, leaving him and Jared trapped until his dad broke the door down with his shoulder, reached over the dresser, and grabbed the kids with one arm and pulled them out as they rode out the rest of the 6.7 earthquake huddled together in the hallway.

The floor was littered with broken glass. Everything that was in the kitchen cabinets — dishes, glasses, pots and pans — fell out and became a two-foot high pile of debris. The water and power were out for six days. The swimming pool was half empty.

“Everything that could’ve fallen, fell and broke,” Gordon, now 42, recalls. “It was just absolutely terrifying.”

Gordon and his Northridge City Little League teammates now remember that summer as the time their world was turned upside down until their magical run to Williamsport, Pa., provided profound and cathartic joy.

Interstate 10 split and collapsed over La Cienega Boulevard following the Northridge earthquake on Jan. 17, 1994.

(Eric Draper / Associated Press)

Nathaniel Dunlap felt the earthquake in Riverside, where he was staying for a travel baseball tournament, strongly enough to wake up him and his mother. Attempts to reach his father and grandmother, who had both stayed behind in Northridge, failed. It wasn’t until they turned on the TV in their hotel room and learned the earthquake was centered in his hometown.

To make matters worse, Dunlap and his mom had no way of getting back home. Several overpasses on the 5, 10, 118 and 210 freeways had collapsed, and the ones that still stood were gridlocked in both directions with people either evacuating or trying to get home.

When they were finally able to make the 85-mile drive back to Northridge the next day, Dunlap recalled it was like “driving into a war zone.”

“Our house was still standing, but everything in it was just trashed,” he said.

The Dunlaps — 5-foot-11 Nathaniel, his parents, grandmother, and the family dog spent the next three weeks sleeping in a three-person tent in their backyard, unsure of the extent of the structural damage to the house.

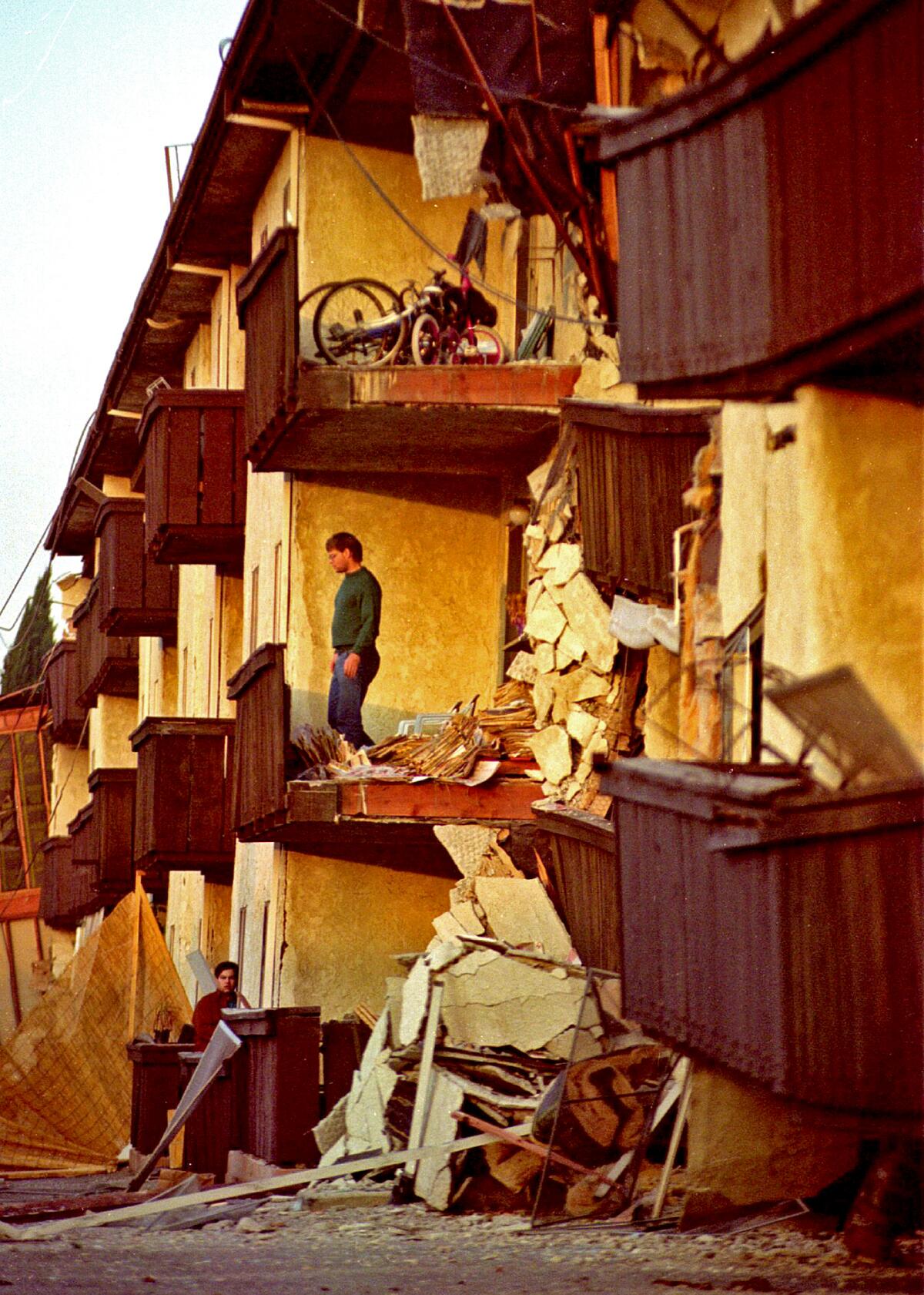

A man stares out to the street from his wall-less home at the devastated Northridge Meadows apartments.

(Los Angeles Times)

“We lived just down the street from Winnetka Park, and if you drove by there in the weeks after the earthquake, it was like tent city,” Dunlap said. “So many people were displaced, either from their homes not being safe or because a lot of the apartments in the area had collapsed or were completely unstable.”

David Teraoka was also without water or power in the aftermath of the earthquake. His family would boil pool water to heat up quick meals such as instant ramen noodles since everything in their refrigerator had spoiled. But most of all, Teraoka remembers there was really nothing for kids to do during that time.

“Anything that was entertainment related was closed,” he said. “The malls, the movie theaters … I remember the feeling was just in awe of seeing some of these buildings down and things closed. [Life] was definitely not normal for a really long time.”

That sense of normalcy didn’t start to return for Teraoka until about a month later, when he was finally able to get back to baseball practice.

“It was just so refreshing … being able to go to the baseball field with your buddies … it was like a good kind of escape,” he said. “I could definitely say it was therapeutic.”

A boy runs by vehicles crushed by an apartment building that collapsed during the Northridge earthquake.

(Roland Otero / Los Angeles Times)

Coach Larry Baca saw his players’ demeanor change once they were back on the field.

“All the time I spent on the baseball field was just fun,” Gordon said. “My teammates were great, hilarious. We were all pranksters and jokesters. … We were all for each other, too.”

“It was great,” Baca said. “They were so happy because there was a sense of calm when they came over to the baseball field. They know their ceiling’s not going to drop [on top of them.]”

Baca also knew how talented they were. He knew that once the All-Star season came around that summer, Northridge City Little League was going to make some noise.

They had a lineup that featured power from batters one through nine, including an especially powerful cleanup hitter in Gordon, two dominant aces on the mound Dunlap and Justin Gentile — and, in Gentile’s case, a leadoff hitter who could also hit for power in games when he wasn’t pitching — a defensive mastermind at catcher in Jonathan Higashi, a silky smooth shortstop in Matt Fisher and a young first baseman by the name of Matt Cassel, who would later go on to have a 14-year career as an NFL quarterback. They also had depth, as Teraoka’s bat provided a spark off the bench.

The only real difference that separated the 1994 team from the 1993 team was that now, as 11-and-12-year olds, they had the opportunity to reach the pinnacle of youth sports: the Little League World Series in Williamsport, Penn.

Some of the kids who had been around for a few years knew this, and they made it a goal from the first All-Star practice when the team gather in the dugout and every player signed a plywood board that read, “NORTHRIDGE IS GOING ALL THE WAY.”

“We were definitely confident,” Dunlap said. “We knew we had something really special.”

And so, the legend of the Earthquake Kids was off and running.

After a dominant 20-0 run through the district, section and regional tournaments to make it to Williamsport, the championship goal was closer than ever.

Northridge drew Brooklyn Central, Minn., in the first pool-play game of the Little League World Series. Dunlap was on the mound, and he still remembers how amped up he was, how much energy he had. His fastball was up to 74 mph (equivalent to a 97 mph fastball in the MLB), but he didn’t have nearly as much command. He gave up four runs on six hits and while the offense mustered two runs of their own, their win streak came to an end when Gordon struck out to end the game. For the first time that summer, Northridge lost.

Gordon was crushed. He felt the weight of that moment collapse on him, and he tearfully blamed himself for the loss to his parents after the game.

“I just didn’t produce,” Gordon said. “I had a chance to be a hero, and I failed. I just felt like a complete failure.”

The loss moved Northridge into the losers’ bracket of the tournament, but they were still very much alive. Baca took a moment to pull Gordon aside and remind him of that.

“Shake it off. We’ll get back there. Nothing to it,” Baca told Gordon.

Baca, nicknamed “Smooth” by the players, had a reputation for sticking with his players through every high and low. He wasn’t quick to sub kids out, wasn’t overly analytical about matchups. He rode with his best nine.

“I treated them like a ballplayer, not a little kid,” Baca said. “… I was a combat soldier. I was a sergeant. And so, I dealt with guys the same way, I treated them with respect.”

That mentality paid off when Gordon, who was one for nine through the first three games of the series, smashed a three-run home run in the first inning of the U.S. Championship game to jump to an early 3-0 lead over Springfield, Va.

“I knew if I just stayed within the moment, I could make something happen,” he said. “I believed in myself, stayed focused and I was able to shake it off. … Baseball is a hard game, it’s a game of failure … it will always keep you humble, and you just have to learn from those moments.”

Those three runs were the only offense of the game. Dunlap was pitching again for Northridge, and he had a different motivation for this game.

The day before the U.S. championship, Baca was by the pay phones in the barracks — where the players and coaches were staying — when he overheard Springfield’s coach, George Lare, who they had already beaten once, speaking with his mother on the phone.

“We play [Northridge] again tomorrow,” Baca heard Lare say. “They have a guy that throws fastballs, but we can hit those.”

When Baca relayed the conversation he heard to Dunlap, it fired him up.

Dunlap’s velocity was down compared to his first start, but he was hitting his spots a lot better as he pitched a no-hitter into the sixth and final inning.

“Every inning was just so smooth,” Dunlap recalled. “It was great.”

Springfield ended Dunlap’s no-hit bid in the sixth on a liner into the outfield. The next batter hit a grounder that took a tough hop and barely missed Matt Fisher’s glove. All of a sudden, the tying run was at the plate with one out.

Dunlap struck out the next batter, and then Ethan Lare — the son of George Lare, the coach who Baca overheard on the phone — came up to bat.

Baca heard George yell to his son, “Watch the curve!”

Baca signaled for Dunlap to throw his fastball. Strike one.

George yelled again for the next pitch, “Watch the curve!”

Baca signaled for another fastball. Strike two.

“Watch the curve!” George shouted for the third time.

Dunlap threw another fastball. Strike three. Northridge City Little League was U.S. champions.

The team took its victory lap, running around the field holding the American flag as the crowd of 20,000 people that packed Howard J. Lamade Stadium chanted “USA! USA! USA!”

“It was otherworldly,” said David Teraoka. “I felt like a rock star, man.”

Northridge advanced to the World Series championship against Maracaibo, Venezuela, where its magical run came to an end with a 4-3 loss and it was time to go back home. The players knew they were known as the Earthquake Kids and their games were being covered by the media and their highlights were on SportsCenter, but as their season progressed, they spent more time isolated in the barracks and didn’t fully grasp their impact back home in Los Angeles.

At least, until their plane landed.

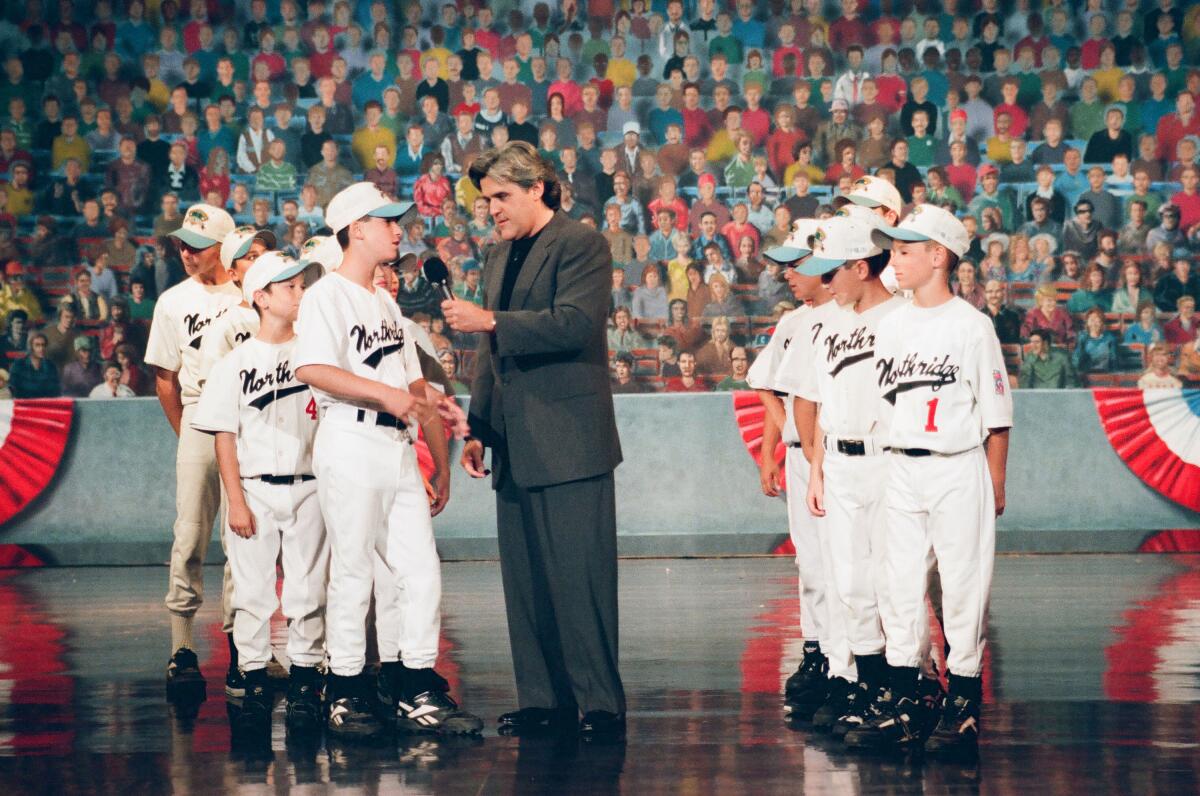

Talk show host Jay Leno interviews the Northridge Little League players on Sept. 5, 1994.

(NBC Universal via Getty Images)

A mob of people — family members, friends and reporters — awaited them at the gate as they arrived at Los Angeles International Airport. Some of them carried signs and almost all of them were cheering and screaming. Once the players made it past the gate, limousines were waiting to pick them up, each overflowing with pizza boxes. They weren’t just the Northridge All-Stars anymore — they were the Earthquake Kids — and they weren’t going home. They were going to K-Earth 101. They were going to Disneyland. They were being introduced at Dodger Stadium. They were meeting Bill Clinton and Ronald Reagan, and then-LA mayor Richard Riordan. They were on Jay Leno. They had cameos in the 1995 film “Three Wishes” starring Patrick Swayze.

They were invited to the Rose Parade. They had a parade thrown in their honor in Northridge, where they were escorted down Devonshire Street and Reseda Boulevard in convertible Corvettes.

“I just think how fortunate we were to have been able to experience that,” said Jonathan Higashi. “And the success that we all had, and all the aftermath of all these things that many people don’t get an opportunity to do. We got to do that.”

Thirty years have passed since their 15 minutes of fame, but the memories from 1994 — both the good and bad — are forever stitched into the fabric of Northridge. Some people lost their homes, others lost their lives or loved ones. A generation of Angelenos is forever scarred by that year. But, however briefly, a group of 11-and-12-year-olds gave their community something to cheer on, something to take pride in and, most of all, hope.

“To be able to have something … innocent to latch onto,” Teraoka said. “For me and my parents, it was a big distraction from the damage to our house and to the community. As an adult, that’s what I look back on. … As a kid, it was just really fun being in that moment.”