Fitness

Roopa Pai – “Yoga looks at holistic well-being, not just fitness”

In The Yoga Sutras for Children, you confess that until recently you “had no idea that yoga was far, far more than postures and pranayama”. Why do you think people believe yoga is restricted to asana practice and breathing techniques? Does this have to do with how yoga is marketed today?

A lot of urban Indians are doing yoga because it is really popular abroad. They are now rediscovering it through the West though it has been in our own backyard all along. If you go to any regular yoga class in India, you’ll see that teachers focus mostly on asanas and pranayama. They even have competitions to see who can put themselves in the most difficult postures. The best ones get picked out, and this becomes material for WhatsApp forwards.

If you look at yoga reels on Instagram, most of them are by white people who seem to reduce yoga to a physical practice that is all about keeping your body fit. They present yoga as one of various things that you could do like running or going to the gym. There’s more to yoga. It looks at holistic well-being, not just fitness. It helps you navigate your inner universe. The main goal is to be calm, to maintain equanimity because there will be ups and downs.

I have signed up for some yoga classes on and off over the years but I got into serious and regular practice only during the COVID-19 pandemic when I needed something to learn to focus and I joined an online yoga class. I have been consistent for four years now. Having an amazing teacher does make a difference, and I must thank mine – Mala Bhat – for that. With her guidance, I have learnt to appreciate how vast, wonderful and beneficial yoga is. Asana practice is meant to help your body become limber so that you can sit longer in meditation.

How did Maharishi Patanjali and the Yoga Sutras come into your life?

During the pandemic, I was also learning Sanskrit online through a course taught by Anuradha Choudry who is based at the Indian Institute of Technology in Kharagpur. I felt this great desire to study the language because I wrote two of my earlier books – The Gita for Children and The Vedas and Upanishads for Children – without any knowledge of Sanskrit. I wrote them based entirely on commentaries by Indian and Western practitioners and scholars.

Since I was also a yoga practitioner, my Sanskrit teacher recommended listening to a lecture on the Yoga Sutras by Vinayachandra Banavathy. He spoke in a straightforward manner, and made the Yoga Sutras feel approachable. There was a deep level of resonance because it was all about calming one’s mind and sharpening one’s ability to achieve anything by being grounded in that calmness. I thought it would be great to introduce this text to young readers.

I was stunned by how succinct and direct the sutras are. Maharishi Patanjali has laid them out very logically like a science textbook. Like any good teacher, he is able to anticipate the questions that a student would have. What is yoga? Why should you do it? What will happen if you don’t it? He addresses everything. He tells you that freedom is guaranteed but you cannot take shortcuts; you won’t get results if you don’t do things as they are meant to be done. Many of us give up and make excuses to not be regular. I felt like he was talking to me. Eventually, it was comforting to know that hard work was all that was expected of me.

Edwin Bryant’s book The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali (2018) was useful to me because he has read all the commentaries on the Yoga Sutras and also given his own take on them. I learnt about this book from Swami Sarvapriyananda’s discourse on the Yoga Sutras. He is the head of the Vedanta Society of New York. I find him lucid, knowledgeable and so humorous!

What gave you the confidence that the sutras would speak to young readers?

I find that younger people feel deeply about everything, whether it is happening in India or Palestine or anywhere else. They feel everybody’s pain intensely but are unable to contribute in any meaningful way to reduce it, so they get frazzled. It is hard for me to watch this, to witness their loss of hope. I thought that learning to manage their emotions would help them see things more clearly, and the clarity would help them contribute positively.

One of your chapters in The Yoga Sutras for Children is titled “You Are Not the Storm; You Are Its Calm Centre”. How have your readers responded to this idea?

They feel empowered when they learn that all their thoughts can be classified into five thought-buckets — pramana (thoughts based on what you have experienced personally, deduced, or been told by someone you trust completely), viparyaya (thoughts based on information gathered from unreliable sources, gossip or rumours), vikalpa (thoughts about the future that have no basis in reality but exist only in your mind), smrityayah (thoughts about events and people in your past); nidra (absence of thought during restful dreamless sleep). The Yoga Sutras talk about how to still the churning of the mind. This is achieved through mindfulness, by stepping back and watching your thoughts with dispassion.

Children are thrilled to know that there is a way to reduce their anxiety, to become happy. There are four simple things that they can do to stay calm – maitri (cultivating friendships with cheerful, positive people), karuna (being compassionate towards those who are sad, confused or bitter), mudita (rejoicing in other people’s joys), upeksha (not taking other people’s words and actions personally, especially when they are mean and hurtful to you). These four things become muscle memory if you practise them diligently and regularly. Your mind does not get clouded by emotion. You are able to practise detachment, which is very different from indifference. Detachment helps you a lot with rational decision-making.

The book is conversational, has references to popular culture, and conveys a lot of complex philosophical ideas. What helped you find the right voice and vocabulary?

Being a writer of children’s books helped. Having worked on The Gita for Children and The Vedas and Upanishads for Children, I felt confident about using a voice that didn’t sound authoritarian and prescriptive. My tone was like this: “Look what I found! This is so exciting.” I wanted to speak to them like a friendly adult. I didn’t want to pretend to be a young person myself. It was important for me to respect their intelligence; not be juvenile.

How much a 10-year-old gets from it will be different from what an 18-year-old might, and that’s alright. I think that The Yoga Sutras for Children is best suited for family reading. When parents ask their children to read the book, and don’t read it themselves, the full potential of the book remains unexplored. When the whole family reads it, they have a common vocabulary and a shared ethical code. Children too feel empowered to keep an eye on adults instead of just the other way round. Everyone in the family can help each other.

Speaking of the voice and vocabulary, I did not want to be irreverent. All these Indic texts have great philosophical depth. They teach us that we are responsible for our own destiny. This thought is terrifying in a sense but it is also quite liberating. You don’t have to believe in an external God judging you. You can look within and have faith in your own higher self.

I have come across urban Indians who feel embarrassed about their interest in these texts because they fear being labelled “bhakt” or “sanghi” if they express this interest openly. Have you encountered this phenomenon? What are your thoughts on this?

Yes, I know what you are talking about and I think that all these labels – “bhakt”, “sanghi”, “libtard” are really stupid. They diminish the person, and trivialize the experience of self-enquiry. Science, philosophy and religion find different ways to approach the same questions. We are an argumentative lot, and the room for doubt is embedded in our oldest texts. Let us celebrate this freedom to stay with an idea, explore it deeply, and question it.

When India put forth a resolution to observe the International Day of Yoga on June 21, it was passed unanimously at the United Nations. What makes this ancient system of knowledge and practice resonate deeply with people in countries across the world?

I think that yoga must be practised not because it’s Indian but because it’s sensible. It is a humanist, universal philosophy aimed at the calming of the mind and attainment of our full potential as human beings. It is not about winning brownie points with God or finding a place in heaven. If you look at the yamas or the list of don’ts, they are a wise set of guidelines — ahimsa (not committing violence in thought, word and deed), satya (not lying but speaking the truth gently), asteya (not stealing people’s things, dignity or their peace), brahmacharya (not frittering away your energy but channelling it into constructive, meaningful work), and aparigraha (not being greedy to have what other have). We also have pointers for what to do in the niyamas — shaucha (keeping body and mind clean); santosha (learning to be grateful and content), tapah (staying committed to your path); svadhyaya (setting aside time for yourself) and Ishvara pranidhana (having faith and praying).

You note that the secret of lasting happiness “isn’t cooler friends or more money or unlimited free pizzas or getting the top rank in an exam or India winning the Cricket World Cup”. What have you learnt about happiness from the Yoga Sutras?

I have learnt that happiness comes and goes. Chasing happiness, or even success, is pointless. What’s worth chasing is fearlessness. If you can act without fear, you can be calm.

Speaking of calmness, what was it like to be in Bhutan to talk about your books? After participating in the Drukyul’s Literature and Arts Festival, did you travel a bit?

I went to Bhutan with zero expectations, and I encountered pleasant surprises at every corner. It was the calmest literary festival that I have ever been to. The organizers were coordinating a lot of things but they never seemed hassled, so I guess they were either very meticulous with planning and delegation of responsibility or they just knew how to keep a cool head. The quality of discussions, and the question-answer sessions were meaningful. Nobody was yelling or even talking loudly. There was this all-pervading sense of serenity. The greenery, cleanliness, and lack of pollution played an important role in how I felt there. My husband and I travelled to Punakha and Paro after the festival. We went to the Tiger’s Nest. It was so peaceful, so beautiful! I did not hear whistles of pressure cookers and the grating sounds of mixer-grinders all the time. Coming from India, one notices all this.

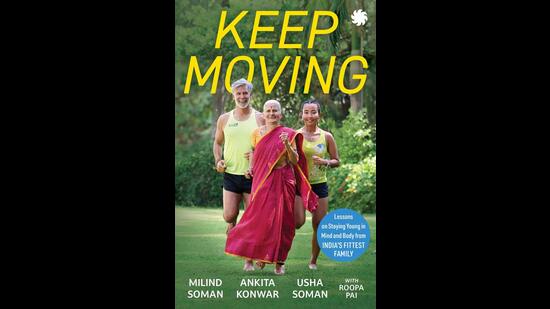

How was it working with Milind Soman, Ankita Konwar and Usha Soman on your latest book Keep Moving: Lessons on Staying Young in Mind and Body from India’s Fittest Family? You have worked with Milind before on his memoir Made in India. How different was it this time since two more members of the family were involved?

It was fun working with them. Milind has got a lot of clarity. He is very comfortable in his skin. With him, there is no celebrity nautanki. I like that. His mother, Usha, is one of the most sorted people I’ve met. His wife, Ankita, could have easily fallen in his shadow but she is very much her own person. That was beautiful to watch. I interviewed each one of them separately, first in Mumbai and then in Goa where I was invited on a lovely staycation with them. I found the family vibe quite non-judgemental and respectful on the whole. They give each other the space to be who they are, and they extended that grace to me as well.

Chintan Girish Modi is a freelance writer, journalist and book reviewer.