World

‘When I was cycling, the world was big again’: What it takes to replace a flight with a long-distance bike ride

Matilda Welin

Matilda WelinLooking for alternatives to flying, Matilda Welin decided to embark on a long-distance cycle from London to Sweden. Here’s what she learned.

Before the advent of fossil fuel-powered transport, travellers crawled across the surface of the planet slowly. The world, back then, was bigger; getting anywhere at all was an adventure in itself. Today, the world is small. I can live my life in London, UK, and still attend family events in Sweden, where I’m from, several times a year. I can have my cake and eat it.

That is, if it weren’t for one thing: the climate. The emissions released by aeroplanes mean flying in them is among the most carbon-intensive things most people are likely to ever do. Trying to avoid these emissions, I have experimented with ferry and train travel between the UK and Sweden for over a decade. But plane is almost always the cheapest option. So what about cycling?

Cycling is one of the greenest and cheapest ways to travel short distances. Longer distance cycle touring, meanwhile, remains a popular holiday option, even gaining new levels of fame as so-called dotwatching enables onlookers to follow “bikepacking” races from their own sofas. But most would consider it impractical to travel the kind of distances covered by planes.

To test out whether it really could be a long-distance travel option for me, in June 2024 I cycled 1,500km (930 miles) from London to Sweden over the course of 17 days.

My bike trip started on the sofa. Normally when I go back home to Sweden, I simply check in at the airport and sit back on board the plane as the pilot whizzes me above forests, towns and mountain ranges. This time, I’d cross every junction, bridge and hillock by myself.

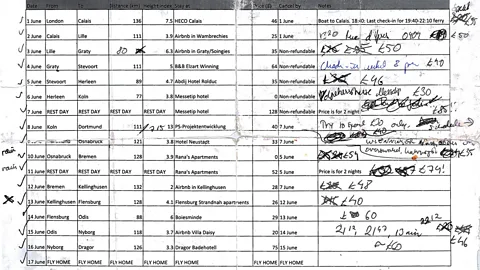

While there are excellent trail networks for those who want well-planned itineraries ready-made, I enjoyed making my own. Night after night, as my partner slept, I poured over outdoor planning apps, cycle apps, Facebook discussion groups and Google Street View. Which sights and cities did I want to see? Which were the safest roads, and – key for a larger person like me – the ones with the least hills? I booked lodgings some 100km (62 miles) apart along the way, cancellable in case of changing plans, and scheduled in two rest-and-catchup days.

Next: the gear. I already owned a bike, obtained through the UK government’s cost-reducing bike-to-work scheme, and £20 ($26) cycle-friendly, padded Lycra shorts, which I paired with the same sports bra and top I’d wear to the gym.

In small panniers I bought on sale for around £50 ($65), I placed my rain jacket, my rain trousers (doubling as rest-day wear), an extra top to sleep in, a fleece jumper and a pair of gloves.

Then came toiletries, a first-aid kit, bike repair tools and my credit card, phone and passport. Once my partner had added a small pink heart as a good-luck token, my budget luggage was complete.

As my departure date drew closer, I did lots of Pilates to pre-empt shoulder and arm fatigue, and I also went on a three-day test ride. The last thing on the to-do list was the scariest: I needed to learn how to fix a flat tyre. Daunted by complicated mechanics, I normally hand my bike in for the simplest of fixes, something that both loses me money and makes me feel like a cliché of an untechnical woman. Now, I spent £85 ($110) on a three-hour bike maintenance course at the London Bike Kitchen. It was expensive, but worth it: afterwards, I changed two punctured inner tubes on my bike all by myself. I was ready to set off.

Matilda Welin

Matilda WelinOn departure day, my alarm went off at 06:00.

“I don’t want to go,” I said to my partner from under the duvet. “Maybe we could just stage pictures of me with German and Dutch backgrounds? No-one needs to know!”

The early morning streets were quiet. I cycled along one of my usual routes downtown, but this time it was different: I wasn’t just riding to see a friend, to a dinner or to a work event – I was riding to Sweden.

Soon I passed our closest train station, and then a museum I had visited and a venue where I’d taken a course. There was the pub I had been to a few times with friends, and the park we went to once for my birthday. The last outpost of the city I knew was a friend’s house far out in the eastern outskirts of London. As the familiar, white building passed on my right-hand side, I looked at the road climbing up a hill ahead. From now on, I was covering new ground.

Over the next 16 days, my life settled into a pleasant rhythm. I cycled across seven countries, passing the English Channel, rivers and straits by boat and train. I acquired unusual tan lines where my bike gloves covered my hands and spent a whole week trying (and failing) to out-cycle rain clouds chasing me across northern Germany. I stayed in cheap hotels, in a Dutch castle, and in people’s homes.

In southern Belgium, I rented a room from local man Pasquale, who lived with his dog, cat and chickens. As I walked around Pasquale’s garden, the two of us used a translation app to cobble French, Dutch, Swedish and English into a functioning conversation. In southern Denmark, an elderly woman rented out rooms in her dreamy country house. As I awoke to pouring rain, she invited me to stay for a few extra hours and made me a jam sandwich which I ate sitting under a woollen blanket, an open window letting in the sound and smell of water on greenery.

Matilda Welin

Matilda WelinEvery morning, I stopped for breakfast at small cafes along the route, and every evening, I hand washed my one set of cycling clothes in the sink. Most of my lodgings cost £20-40 ($26-$52), and I had planned for a daily maximum of £50 ($66) on top of that for food and necessities. But when most of your day is taken up by cycling, you don’t have much time to spend money. Frequently, I went under budget.

Not everything was easy, of course. I was intimidated, harassed by motorbikes and, twice, treated to the cycling-in-traffic hallmark of being shouted at by lads in passing cars. The best defence to any of this, I found, is to know the local bike laws, both so you can stand up to unfair aggression and to be able to join traffic without obstructing it.

On the second to last day of the ride, I suddenly got increasingly fatigued – a lack of glucose known in cycling circles as bonking (no sniggering in the back!). When I finally arrived in the next town and sat down to eat, I texted my partner to tell him what had happened. “You could just stay where you are overnight,” he suggested. But in the end, I kept going.

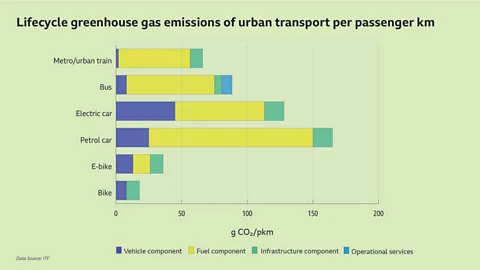

Safely home again, I tried to calculate my emissions. It is a tricky estimate to make. Should I include the life cycle analysis of the building of my bike, the roads I travelled on, the hotels I slept in and the food I ate to propel myself forward? I asked several experts, but none could give me a simple answer.

“There is quite a lot of data out there that looks at life cycle emissions of different types of urban transport modes,” says Dana Yanocha, senior research manager at the Institute for Transport and Development Policy (ITDP) in the US. Shorter journeys of 20km (12 miles) or less within a city by bike, bus, taxi, car or motorbike can be compared at a passenger kilometre level, she explains. But the measurements aren’t necessarily expandable to my 17-day ride.

BBC/ITF

BBC/ITFBut not all environmental benefits are measurable in emission units. “The bigger picture takeaway [with a long-distance ride] would be getting the conversation in people’s minds,” Yanocha says. “You would automatically think ‘oh, I’m just going to fly’, [but] actually you could do this on a bike.”

Cycling helps us appreciate nature, says Brandi Horton, vice president of communication at the US non-profit Rails to Trails Conservancy. “When you’re zooming around in your car or you’re on the train or you’re on a plane, you are not going slow enough to notice what lives [around] you. When you’re off the highway… you suddenly see something entirely different.”

Long-distance cyclists, Horton says, can also help raise the demand for cycle trails that locals can use, too. “We cannot meet our [pollution] target if we don’t get people out of their cars more often. And the only way we’re getting people out of their cars more often is to create the infrastructure that makes it safe and convenient for them to do that.”

Carbon Count

The emissions from travel it took to report this story were 0kg CO2, as Matilda undertook her bike trip in a personal capacity. See the story for more on the potential emissions from her trip. The digital emissions from this story are an estimated 1.2g to 3.6g CO2 per page view. Find out more about how we calculated this figure here.

During my trip, one thing affected my view of long-distance transport more than anything else. As I pedalled, I felt I was I experiencing the true distance of the journey I take so casually and so often with a plane. The world around me changed slowly.

English became French, and French became Dutch. Dutch was replaced by German, Danish and Swedish. During the first days of my ride, old people outside cafes stopped to stare at me in awe. But as I rolled into northern German town Bremen in the pouring rain, I was no longer special: here everyone cycled, in ponchos or full-body waterproof gear.

The big town squares of northern France and southern Belgium gave way to well-planned German cities and Danish towns. The landscape changed from canal-streaked flat Atlantic plains to the mountainous Bergisches Land, then Danish forests. Never before had I internalised what a massive amount of energy my two-and-a-half-hour plane journey really needed.

Matilda Welin

Matilda WelinSooner than I wanted, I arrived in the southern Swedish town of Trelleborg, just south of Malmö. Did my ride benefit the planet and save me money? In hard terms, neither. I did save on a plane journey, but once I had met up with my mum for a few hours, I had to fly myself and my bicycle straight back to London to get back to the office. So in the end I used an aeroplane anyway and didn’t really have time to hang out with my family at all. My total spend while on the road was around £1,400 ($1,830) – much more than a plane ticket at around £100 ($130) or a train one at £350 ($460) or so.

On the other hand, this price also included an unforgettable journey. And replacing train journeys with cycling ones certainly doesn’t have to mean picking a trip as long as this one. Next time, I may take a few days to cycle from London to Burnley, or from Stockholm to my dad’s house a few dozen miles north of town. I know now it is possible, as long as you prepare yourself well.

My trip also changed my view of how the transport we use shrinks the world. As Horton told me, when you cycle or walk, you experience the world around you “at human speed”. When I was cycling, the world was big again.