Tech

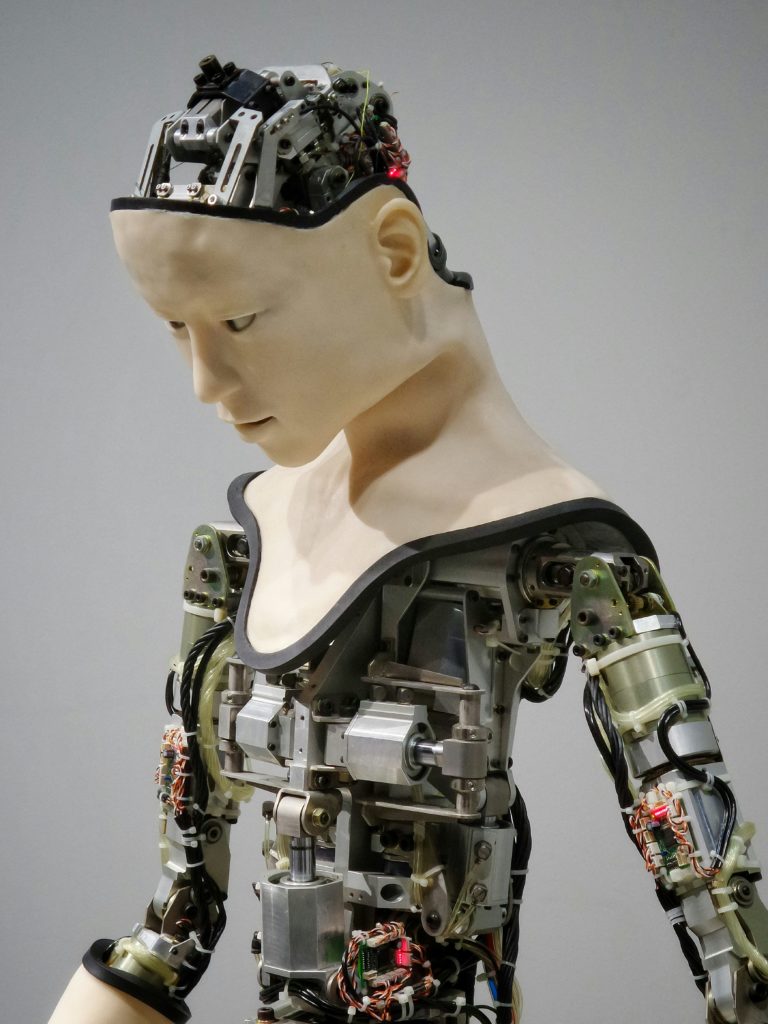

Humanizing Chatbots Is Hard To Resist — But Why?

Written by Madeline G. Reinecke (@mgreinecke)

You might recall a story from a few years ago, concerning former Google software engineer Blake Lemoine. Part of Lemoine’s job was to chat with LaMDA, a large language model (LLM) in development at the time, to detect discriminatory speech. But the more Lemoine chatted with LaMDA, the more he became convinced: The model had become sentient and was being deprived of its rights as a Google employee.

Though Google swiftly denied Lemoine’s claims, I’ve since wondered whether this anthropomorphic phenomenon — seeing a “mind in the machine” — might be a common occurrence in LLM users. In fact, in this post, I’ll argue that it’s bound to be common, and perhaps even irresistible, due to basic facts about human psychology.

Emerging work suggests that a non-trivial number of people do attribute humanlike characteristics to LLM-based chatbots. This is to say they “anthropomorphize” them. In one study, 67% of participants attributed some degree of phenomenal consciousness to ChatGPT: saying, basically, there is “something it is like” to be ChatGPT. In a separate survey, researchers showed participants actual ChatGPT transcripts, explaining that they were generated by an LLM. Actually seeing the natural language “skills” of ChatGPT further increased participants’ tendency to anthropomorphize the model. These effects were especially pronounced for frequent LLM users.

Why does anthropomorphism of these technologies come so easily? Is it irresistible, as I’ve suggested, given features of human psychology?

In a preprint with Fransisca Ting, Julian Savulescu, and Ilina Singh, we consider some of the human cognitive mechanisms that may underpin LLM-oriented anthropomorphism.

For example, humans often “see” agency where there isn’t any. In a famous psychology study now taught as a classic, researchers Heider and Simmel presented participants with a short stop-motion video of shapes moving about a screen. The participants were then tasked to “write down what they saw happen in the picture.” Of all of the participants tested, only one described the scene in purely geometric terms. Everyone else “anthropomorphized” the shapes — describing them as fighting, chasing, wanting to escape, and so on.

If you haven’t seen the video before, do give it a look. It’s hard not to see the shapes as little agents, pursuing various ends.

This tendency may be a feature — rather than a bug — of human psychology. One theory suggests that in the ancestral environment of our species, it was adaptive to over-detect agency. Basically, If you’re on an African savanna and hear an ambiguous rustle in the grass behind you, better to assume it might be a predator than a gust of wind (lest you end up as prey). Put another way: a false positive causes a mild annoyance; a false negative causes a threat to survival.

We further argue that LLMs’ command of natural language serves as a psychological signal of agency. Even little babies see communication as a sign of agency. In studies looking at how preverbal infants interpret different kinds of agentive signals, being able to communicate often outperforms other metrics, like, being physically similar to typical agents.

Why might that be so? One idea is that communication only makes sense when there are agents involved. Language is what allows us to “share knowledge, thoughts, and feelings with one another.” This link between communicative ability and agency — embedded in human cognition over millions of years — may be hard to override.

LLM-oriented anthropomorphism raises a range of ethical concerns (see Chapter 10 of Gabriel et al., 2024). In our paper, the chief worry we raise surrounds hallucination. Nowadays, one of the most common use cases for LLM-based products is information-finding. But what if the information reported by LLMs is inaccurate? We are far more likely to trust an anthropomorphic AI over a non-anthropomorphic one, which complicates users’ ability to parse truth from falsity when interacting with models.

Though Internet users, more generally, should try to find the right balance between trust and skepticism in evaluating online content, the risk of internalizing misinformation is magnified in a world with anthropomorphic AI.

So, what should we do? My own take is that AI developers have a key responsibility here. Their design choices — like whether an LLM uses first-personal pronouns or not — determine how much users will anthropomorphize a given system. OpenAI, for example, presents a disclaimer at the bottom of the screen when using their products. But is stating that “ChatGPT can make mistakes” sufficient warning for users? Is it enough to protect them from the pitfalls of LLM-oriented anthropomorphism?

At the end of our paper, we gesture at one possible intervention which AI developers might use, inspired by existing techniques to combat misinformation. But even this may fail to override the deep tendencies of the human mind, like the ones described in this post. A priority for future research should be to see whether good technology design can help us resist the irresistible.

Acknowledgments. Thank you to Brian Earp for editorial feedback on an earlier version of this post.

References

Barrett, J. L. (2000). Exploring the natural foundations of religion. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 4(1), 29-34.

Beier, J. S., & Carey, S. (2014). Contingency is not enough: Social context guides third-party attributions of intentional agency. Developmental Psychology, 50(3), 889.

Cohn, M., Pushkarna, M., Olanubi, G. O., Moran, J. M., Padgett, D., Mengesha, Z., & Heldreth, C. (2024). Believing Anthropomorphism: Examining the Role of Anthropomorphic Cues on Trust in Large Language Models. In Extended Abstracts of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems.

Colombatto, C., & Fleming, S. M. (2024). Folk psychological attributions of consciousness to large language models. Neuroscience of Consciousness, 2024(1).

Fedorenko, E., Piantadosi, S. T., & Gibson, E. A. (2024). Language is primarily a tool for communication rather than thought. Nature, 630(8017), 575-586.

Freeman, J. (2024). Provide or Punish? Students’ Views on Generative AI in Higher Education. Higher Education Policy Institute.

Gabriel, I., Manzini, A., Keeling, G., Hendricks, L. A., Rieser, V., Iqbal, H., … & Manyika, J. (2024, preprint). The ethics of advanced AI assistants. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.16244.

Heider, F., & Simmel, M. (1944). An experimental study of apparent behavior. The American Journal of Psychology, 57(2), 243-259.

Jacobs, O., Pazhoohi, F., & Kingstone, A. (2023, preprint). Brief exposure increases mind perception to ChatGPT and is moderated by the individual propensity to anthropomorphize.

Reinecke, M.G., Ting, F., Savulescu, J., & Singh, I. (2024, preprint). The double-edged sword of anthropomorphism in LLMs.

Wertheimer, T. (2022). Blake Lemoine: Google fires engineer who said AI tech has feelings. BBC News.