World

Inside TSMC’s struggle to build a chip factory in the U.S. suburbs

Bruce thought he’d landed his dream job. The young American engineer had been eager for a stable, high-paying job in the semiconductor industry. Then, in late 2020, he received a LinkedIn message from a recruiter for Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company. Bruce read up on TSMC — the leading global manufacturer of advanced chips — and got excited. The job sounded like he’d be “pushing the boundaries of human technology,” he recalled to Rest of World.

TSMC was undergoing a transformation at just about the same time Bruce heard from the recruiter. The coronavirus pandemic was exposing deep faults in supply chains, and a global chip shortage had slowed production of cars, smartphones, and refrigerators around the world. Meanwhile, American policymakers were rallying around what would eventually become the CHIPS and Science Act, a sweeping piece of legislation designed to boost semiconductor manufacturing in the U.S. TSMC, which makes most of its chips in Taiwan, was under pressure to expand its global manufacturing capacities.

Bruce would be working as a semiconductor engineer. The recruiter explained that he would first spend more than a year in Taiwan learning the ins and outs of the complex chipmaking process. Then, he’d return to Arizona. There, in a cactus-dotted suburb of Phoenix, TSMC was building a sprawling new factory to make the kind of chips that power iPhones and U.S. fighter jets. He’d be helping bring America’s newest chip factory online. Bruce was in.

But over the next two years, Bruce came to realize that the reality of working at TSMC wasn’t exactly what he had envisioned. While working on nanometer-level processes to make state-of-the-art chips, he struggled with language barriers, long hours, and a strict hierarchy. Bruce soon began second-guessing what he had signed up for. The plant, which was originally set to begin operating in 2024, fell woefully behind schedule; production at the facility is now set to start in 2025. Bruce, who said he signed a confidentiality agreement with TSMC, requested anonymity for this story.

He wasn’t the only one disappointed with TSMC’s progress in Arizona — other U.S. workers who spoke to Rest of World echoed Bruce’s concerns. In the past two years, the company has relocated hundreds of Taiwanese workers and their families to Arizona. Instead of a gleaming new facility, these workers found an active construction site, and a company struggling to bridge Taiwanese and American professional and cultural norms.

Over the past four months, Rest of World spoke with more than 20 current and former TSMC employees — from the U.S. and Taiwan — at the Arizona plant. All of them requested anonymity because they were not authorized to speak to the media or because they feared retaliation from the company. In February, Rest of World traveled to Phoenix to visit the growing TSMC complex and spend time with the nascent community of transplanted Taiwanese engineers.

The American engineers complained of rigid, counterproductive hierarchies at the company; Taiwanese TSMC veterans described their American counterparts as lacking the kind of dedication and obedience they believe to be the foundation of their company’s world-leading success.

Some 2,200 employees now work at TSMC’s Arizona plant, with about half of them deployed from Taiwan. While tension at the plant simmers, TSMC has been ramping up its investments, recently securing billions of dollars in grants and loans from the U.S. government. Whether or not the plant succeeds in making cutting-edge chips with the same speed, efficiency, and profitability as facilities in Asia remains to be seen, with many skeptical about a U.S. workforce under TSMC’s army-like command system. “[The company] tried to make Arizona Taiwanese,” G. Dan Hutcheson, a semiconductor industry analyst at the research firm TechInsights, told Rest of World. “And it’s just not going to work.”

TSMC did not respond to a detailed list of questions from Rest of World.

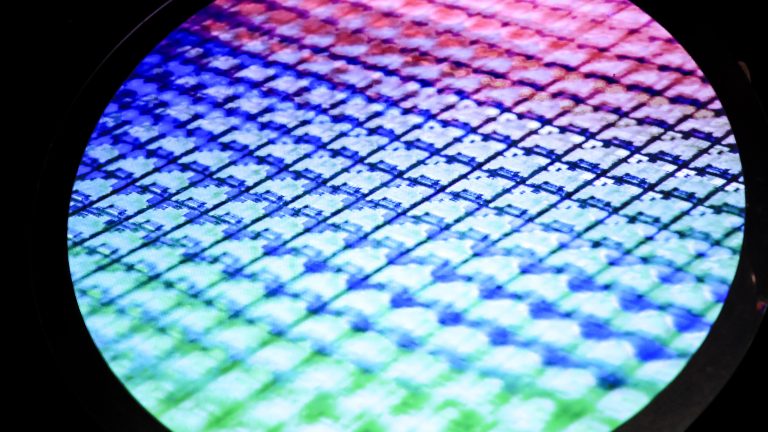

TSMC’s facilities are located on the outskirts of northern Phoenix, surrounded by miles of desert hills and wide roads. A glass-walled office building sits next to a massive parking lot, with a fountain in the shape of a round silicon wafer just in front of the facility gates.

Next to the office building are the incomplete manufacturing facilities. Originally slated to open in 2024, the facilities resemble giant stadiums. Once complete, the entire complex will cover 1,100 acres, or the equivalent of 625 football fields.

At lunch hour on a Monday in February, Taiwanese and American engineers walked in and out of the office building with badges, hard hats, and see-through backpacks — which make it easier and faster for workers to pass through security checks.

TSMC got its start thousands of miles away from Arizona’s arid desert — on the northern coast of Taiwan. Morris Chang, a U.S.-educated chip engineer who spent 25 years at Texas Instruments, founded the company in 1987. He did so at the invitation of the Taiwanese government, which was eager to boost the island’s economy at the time.

Adriana Zehbrauskas/The New York Times/Redux

In the 1980s, companies like Intel and Texas Instruments designed and made their own chips. TSMC set out to do something different. Chang’s company would focus solely on contract manufacturing: Customers would send designs, and engineers in the company’s fabrication plants (also called “fabs”) worked to perfect production methods, minimize the number of defective chips, and reduce costs.

The model proved a success. “All of a sudden it’s really efficient,” Hutcheson, of TechInsights, told Rest of World. “You can learn to become a plumber. But at the end of the day, it’s more efficient for you to focus on what you make money doing and then pay someone else to come do [the plumbing].”

Maps: Cengiz Yar/Joanne Lee/Rest of World, Satellite image: 2024 Maxar Technologies/Getty Images

Meanwhile, chip manufacturing collapsed in the U.S. and Europe, and migrated to East Asia, drawn by government incentives. Hutcheson said the high costs of building new facilities prevented new companies from joining the competition and eventually solidified TSMC’s dominance.

TSMC has since grown into a $660 billion giant that has allowed “fabless” chip designers such as Nvidia and Apple to flourish. The company is now able to cram more computing power into less space than almost any other chip manufacturer. Samsung and Intel are still trailing behind the Taiwanese company.

TSMC is also considered Taiwan’s most important company, with Taiwanese people dubbing it a “divine mountain that guards the nation.” The world’s dependence on TSMC, locals reason, could even incentivize the West to defend Taiwan from a potential invasion from China. The loss of Taiwan and with it TSMC — the thinking goes — would result in a global tech meltdown.

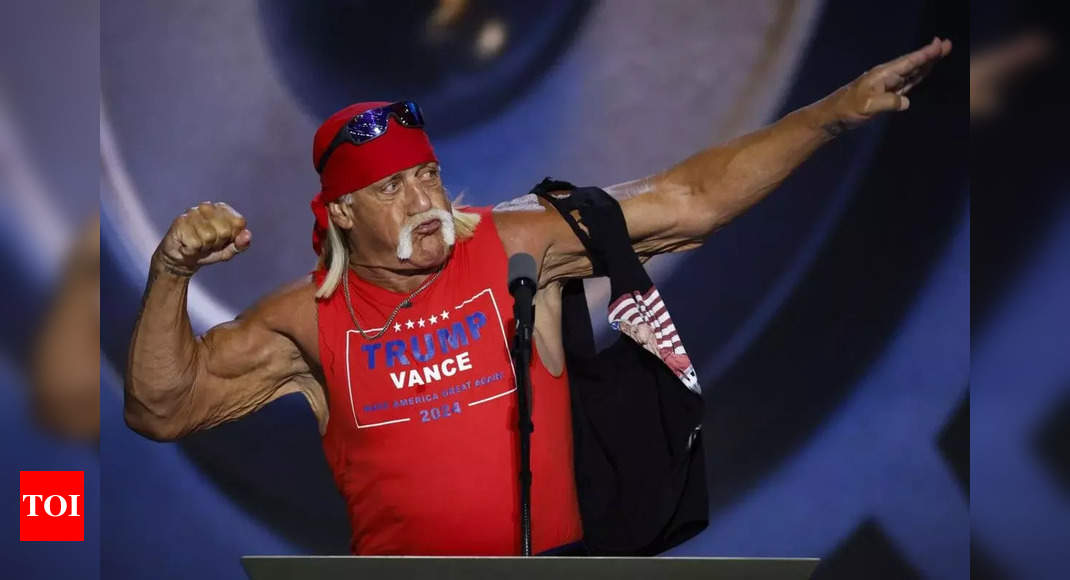

Jonathan Ernst/Reuters/Redux

TSMC insiders told Rest of World the key to the company’s success is an intense, military-style work environment. Engineers work 12-hour days, and sometimes weekends too. Taiwanese commentators joke that the company runs on engineers with “slave mentalities” who “sell their livers” — local slang that underscores the intensity of the work.

Up until the pandemic, it made sense for TSMC to concentrate its operations in Taiwan, where it enjoyed unwavering government support, low operating costs, and access to the island’s top talents. Outside a small plant in Washington and two plants in mainland China that made chips with older technologies, the company had little interest in international expansion.

“The world has changed.”

That changed in the late 2010s, as governments came to realize the geopolitical importance of the semiconductor industry and launched a race to attract chip manufacturing giants. Around 2019, the Trump administration started courting TSMC to build a larger and more advanced plant in the U.S. The pandemic further underscored supply-chain weak points. “The world has changed,” Sujai Shivakumar, director of the Renewing American Innovation Project at the think tank Center for Strategic and International Studies, told Rest of World. Depending on chips from a faraway country on China’s doorstep suddenly felt precarious. “What was purely — from an economics point of view — an efficient solution is no longer an efficient solution because of the geopolitics,” Shivakumar said.

In May 2020, then U.S. Under-Secretary of State Keith Krach announced that TSMC had agreed to open a $12 billion facility in Arizona. The site would create thousands of jobs, spur cutting-edge research, and attract more companies on the semiconductor supply chain to move to the U.S. Chips coming out of the plant were expected to power smartphones, 5G base stations, and advanced F-35 fighter jets. “This means that chips critical to our lives and national security will once again be made in America,” Krach said.

TSMC’s investment, Krach later told U.S. media, inspired policymakers to extend incentives to the entire chip industry. In the summer of 2022, the Biden administration passed the CHIPS Act, which designated $53 billion to developing the domestic semiconductor industry. Later that year, TSMC said it would build a second fab at the same site in Phoenix, increasing its total investment to $40 billion.

Brendan Smialowski/AFP/Getty Images

Despite the commitment from both TSMC and Washington, issues related to exporting a Taiwanese-style work culture to the U.S. swirled from the outset. Morris Chang, who retired in 2018 but remains the public face of the company and the godfather of Taiwan’s semiconductor industry, cast doubts on the Phoenix initiative.

When Nancy Pelosi visited Taiwan in 2022, Chang lectured the House speaker on the challenges the U.S. would face in mastering the microscopic precision required in chip production. Chang has since also warned against the lack of manufacturing talent in the U.S., and how hard it would be for Taiwanese managers to supervise Americans. Speaking to the Vying for Talent podcast in April 2022, Chang concluded that the U.S.’ attempt to onshore semiconductor manufacturing would be “a very expensive exercise in futility.”

In 2021, as construction kicked off in Arizona, TSMC flew Bruce and about 600 American new hires to the southern Taiwanese coastal city of Tainan. There, they’d spend more than a year training at Fab 18, TSMC’s most advanced mass production plant.

Upon arriving at the facility, Bruce handed in his smartphone and passed through metal detectors. He was in awe of the semiconductor production line: Overhead rails carried wafers from one station to another while workers in white protective suits kept the machinery running. “It really just felt like I was touring some kind of living thing that was greater than humans; that was bigger than us,” Bruce recalled.

But the challenges were immediately apparent, too. At Fab 18, nearly all communication took place in Taiwanese and Mandarin Chinese, the two most widely spoken languages in Taiwan. The Americans found it difficult to understand meetings, production guidelines, and chatter among local engineers. In theory, every American was supposed to have a Taiwanese buddy — a future Arizona worker who would help them navigate the workplace. But the Americans said their buddies were often too busy to help with translations, or else not familiar enough with the technical processes because they were freshly transferred from other production lines.

Many trainees, including Bruce, relied on Google Translate to get through the day, with mixed results. Technical terms and images were hard to decipher. One American engineer said that because staff were not allowed to upload work materials to Google, he tried to translate documents by copying Chinese text into a handwriting recognition program. It didn’t work very well.

One former American TSMC engineer who trained in Taiwan said his manager instructed him to follow along with daily handover meetings, which were conducted in Mandarin, just by looking at the associated PowerPoint presentations. “I was mind-blown at his expectations,” he told Rest of World. “I love challenges and pushing myself, but this was lunatic-level leadership.”

Chris Stowers/Panos Pictures/Redux

TSMC’s work culture is notoriously rigorous, even by Taiwanese standards. Former executives have hailed the Confucian culture, which promotes diligence and respect for authority, as well as Taiwan’s strict work ethic as key to the company’s success. Chang, speaking last year about Taiwan’s competitiveness compared to the U.S., said that “if [a machine] breaks down at one in the morning, in the U.S. it will be fixed in the next morning. But in Taiwan, it will be fixed at 2 a.m.” And, he added, the wife of a Taiwanese engineer would “go back to sleep without saying another word.”

During their visit, the Americans got a taste of the company’s intense work culture. To avoid intellectual property leaks, staff were banned from using personal devices inside the factory. Instead, they were given company phones, dubbed “T phones,” that couldn’t be connected to most messaging apps or social media. In one department, managers sometimes applied what they called “stress tests” by announcing assignments due the same day or week, to make sure the Americans were able to meet tight deadlines and sacrifice personal time like Taiwanese workers, two engineers told Rest of World. Managers shamed American workers in front of their peers, sometimes by suggesting they quit engineering, one employee said.

TSMC made attempts to bridge some of the cultural differences. After the American trainees asked to contact families and to listen to music at work, TSMC loosened the firewall on T phones to allow all staff access to Instagram, YouTube, and Spotify. Some Taiwanese workers attended a class on U.S. culture, where they learned that Americans responded better to encouragement rather than criticism, according to an engineer who attended the session.

Lam Yik Fei/Bloomberg/Redux

But both American and Taiwanese engineers said that the training for new hires was largely insufficient. Managers excluded Americans from higher-level meetings conducted in Mandarin, according to one ex-TSMC engineer. Some of the Americans said that they rarely had a chance to handle problems themselves, and were mostly tasked with observing. “It’s like math in school,” Bruce said. “You can watch your teacher do 500 practice problems on the chalkboard, but if you don’t do some problems on your own, you are going to fail the test.”

As training went on, tensions mounted. U.S. engineers told Rest of World that some Taiwanese male engineers had calendars with bikini models on their desks and occasionally shared sexual memes in group chats. A female American colleague, according to an American trainee who witnessed the conversation, asked a Taiwanese engineer to remove his computer wallpaper depicting a bikini model. One former American engineer said some local co-workers referred to him as a “white breeding pig,” implying he was only in Taiwan to sleep with local women. At a meeting, a manager said Americans were less desirable than Taiwanese and Indian workers, according to people who saw leaked notes, which circulated among trainees.

I-Hwa Cheng/Bloomberg/Getty Images

“They really are trying to push this narrative that Americans are slower because of lower technical ability, but I really don’t believe that’s the truth,” an American engineer who recently left TSMC told Rest of World. “The Taiwanese create this false sense of urgency with every single task, and they really push ‘you need to finish everything immediately.’ But it’s just not realistic for people that want to have some normal work-life balance.”

Several former American employees said they were not against working longer hours, but only if the tasks were meaningful. “I’d ask my manager ‘What’s your top priority,’ he’d always say ‘Everything is a priority,’” said another ex-TSMC engineer. “So, so, so, many times I would work overtime getting stuff done only to find out it wasn’t needed.”

Training in Taiwan, which typically lasted one to two years, wasn’t all miserable, the Americans said. On the weekends, the trainees traveled across the island, marveling at the country’s highly efficient public transport network. Bruce spent his weekends hiking and frequenting nightclubs. He chatted with the families that run night-market food stalls, and entertained strangers who requested selfies with foreigners.

Still, at least dozens of trainees quit before the end of training, according to the American employees. TSMC announced a recurring retention bonus in 2022. The remaining American workers began speculating that the company only hired them to secure CHIPS Act funding, Bruce said. But he stayed on: He wanted to see TSMC come to life in Arizona.

In late 2022, the employees began migrating from humid southern Taiwan to the desert of northern Phoenix. The group included the Americans, as well as hundreds of Taiwanese employees who would help install tools, manage suppliers, and prepare the Arizona plant for mass production.

For the Taiwanese, many of whom planned for extended stays in Phoenix, that meant relocating entire families — toddlers and dogs included — to a foreign country. Many regarded it as a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to explore the world, practice English, and send their children to American schools. Younger families planned pregnancies so they could give birth to American citizens. “If we are going to have children, of course we will have them here,” a Taiwanese engineer told Rest of World. “As an American citizen, they will have more options than others.”

To cover the high living costs, TSMC provided the Taiwanese workers with stipend for cars and housing. Some families moved into apartment complexes reserved for employees, dubbed “TSMC villages.” Local schools introduced Mandarin visual aids in classrooms for Taiwanese pupils. A Chinese Baptist church in Phoenix organized English-language classes, taught by earlier generations of Taiwanese immigrants, to help the newcomers settle in.

Many experienced a culture shock. The bustling cities of Taiwan are densely packed and offer extensive public transport, ubiquitous street food, and 24-hour convenience stores every few blocks. In northern Phoenix, everyday life is impossible without a car, and East Asian faces are scarce. “Everything is so big in America,” said one engineer, recalling his first impression. He recounted his wife summarizing her impression of the U.S.: “Great mountains, great rivers, and great boredom.”

The Taiwanese engineers brought with them the intense TSMC work culture. Having spent years under the company’s grueling management, they were used to long days, out-of-hours calls, and harsh treatment from their managers. In Taiwan, the pay and prestige were worth it, they told Rest of World — despite the challenges, many felt proud working for the island’s most prominent firm. It was the best job they could hope for.

But the American workers didn’t have the same sense of loyalty. In the U.S., engineers had a plethora of job options that provided competitive pay and abundant personal time. The Taiwanese workers described their Phoenix colleagues as arrogant, carefree, and more willing to challenge orders. “It’s hard to get them to do things,” a Taiwanese engineer in Phoenix told Rest of World.

Bruce said that working conditions didn’t improve for the Americans once they relocated to Arizona. The American workers did not get more say in how the company was run, and they found the obsequiousness of their Taiwanese colleagues irritating. TSMC workers were asked to draw up reports and keep other documents in a PowerPoint format so that they could regularly make presentations to upper management. The Taiwanese employees were used to it, while the Americans became impatient with typing up weekly work reports. The Americans also resented that Taiwanese colleagues stayed late at the office for no good reason. “That pisses me off,” Bruce said. “They were just doing it for show.”

Five former employees from the U.S. told Rest of World that TSMC engineers sometimes falsified or cherry-picked data for customers and managers. Sometimes, the engineers said, staff would manipulate data from testing tools or wafers to please managers who had seemingly impossible expectations. Other times, one engineer said, “because the workers were spread so thin, anything they could do to get work off their plate they would do.” Four American employees described TSMC culture as “save face”: Workers would strive to make a team, a department, or the company look good at the expense of efficiency and employee wellbeing.

In mid-2023, TSMC announced delays in the construction of its first facility in Arizona, dubbed Fab 21 — production at the facility would start in 2025 instead of 2024 as planned. TSMC blamed a shortage of skilled workers. Construction unions, however, complained of safety hazards and questioned if TSMC was using this as an excuse to bring in cheap labor from Taiwan.

Engineers who were supposed to run production lines were reassigned to work remotely for Fab 18 back in Tainan, and asked to join late-night meetings. Some Americans and Taiwanese engineers were reassigned to help speed up the building of the facility, and asked to oversee construction workers. Clad in their clean-room suits and hard hats, engineers would sometimes collect trash at the unfinished sites. One ex-employee recalled colleagues collecting bottles of urine left by construction crews.

Just like in Taiwan, language barriers contributed to tension in Phoenix. Bruce said his department manager, who had come from Taiwan, spoke poor English. So instead of communicating with Bruce directly, he’d channel feedback or instructions through a Taiwanese colleague. One U.S. engineer said managers trusted Taiwanese workers with important tasks, starving the Americans of hands-on experience. One ex-employee later joked that the biggest skill he learned at TSMC was making PowerPoint slides.

Disgruntled Americans flocked to post complaints to workplace review website Glassdoor, reporting long hours, high stress, unrealistic deadlines, and “Asian culture.” TSMC currently has a rating of 3.2 out of 5 stars on the site. American chipmakers Intel and Texas Instruments, by comparison, have a 4.1 rating. The poor Glassdoor rating made it more difficult for TSMC to hire experienced American workers, a former TSMC manager told Rest of World. Another former employee said he convinced six engineer friends to turn down offers from TSMC.

“TSMC was the worst possible place to work on Earth.”

The company made further attempts to adapt to American work culture. In early 2023, TSMC held weekly English-language and cultural classes for Taiwanese managers. A former TSMC staffer who worked on the education program said managers were instructed not to yell at employees in public, or threaten to fire them without consulting human resources. “They would say, ‘Okay, okay, I get it. I’m not going to do that,’” the employee recalled to Rest of World. “But I think in the heat of the moment, they forgot, and they did do it.”

Taiwanese managers were reminded not to ask employees why they were taking sick leave, or ask female job applicants about their plans to have children — an illegal yet common question in Taiwan. An ex-TSMC engineer said the company once sent an email reminding staff that the commonly used Mandarin term “nei ge” — which means “that” — could sound like the N-word.

In December 2023, following months of negotiations, TSMC made a deal with Arizona construction labor unions, agreeing to develop a workforce training program, maintain transparency on site safety, and focus on hiring locally.

Meanwhile, some American engineers started seeking out opportunities at companies with less strenuous expectations and better career prospects. Workers started joking that joining TSMC was a stepping stone to Intel, which was also expanding in Arizona at the time. An engineer, who has worked at both Intel and TSMC, said Taiwanese colleagues had also asked him about vacancies at Intel, where they expected a better work-and-life balance.

Several American former employees said they felt relief after quitting. In group chats, engineers celebrated the departure of their friends. “TSMC was the worst possible place to work on Earth,” one American ex-TSMC engineer told Rest of World. Another, who recently left the company, described TSMC as having “a purely authoritarian work structure.”

Bruce resigned in 2023. He is still friends with his Taiwanese former colleagues, and kept his TSMC badge, water bottle, and TSMC T-shirt as mementos. He said he felt triumphant walking out. The American workers had voiced their concerns in meetings with management, but he didn’t see changes happening. “All of us gave them every chance to listen, but they never did,” he told Rest of World.

Three years after construction began, the first planned Phoenix plant is still incomplete. During an earnings call in April, TSMC chief executive C.C. Wei said the facility had entered “engineering wafer production,” meaning it’s making prototype wafers to prepare for commercial operation next year. In January, TSMC announced further delays at its second facility, too. Originally set to begin operations in 2026, it won’t open until 2027 or 2028.

Chang-Tai Hsieh, an economics professor at the University of Chicago, told Rest of World that TSMC had found the U.S. a challenging environment to operate in because of the complicated regulatory process, strong construction unions, and a workforce less used to the long hours that are commonplace at TSMC in Taiwan. “TSMC’s profits from their U.S. fabs will be lower, unless their clients are willing to pay more to source from the U.S. fabs,” Hsieh said. “The only thing they need Phoenix for is to make sure that the U.S. government doesn’t turn against them.” In 2023, TSMC made more than 65% of its revenue from customers in the U.S. In the April earnings call, chief executive Wei said customers needed to share the high costs of producing outside Taiwan.

“The only thing they need Phoenix for is to make sure that the U.S. government doesn’t turn against them.”

That same month, following years of negotiations, the U.S. government announced plans to award TSMC $6.6 billion in grants and about $5 billion in loans, with TSMC agreeing to construct a third factory on its Phoenix site that will start operating by the end of the decade. (Meanwhile, Intel was awarded $8.5 billion in grants in March, and Samsung was provided $6.4 billion in direct funding in April.)

Despite the flood of investments, the U.S. has a long way to go before chip self-reliance, experts told Rest of World. TSMC Arizona’s first two facilities are expected to make 600,000 wafers a year — a fraction of the company’s current annual capacity of 16 million wafers. Many of the chips made in the U.S. still need to be shipped back to Asia for assembly, testing, and packaging. Chip packaging company Amkor, which has most of its factories in Asia, will build a plant in Arizona to package Apple chips made at TSMC.

The U.S. needs to offer timely, consistent support to companies like TSMC in order to create the kind of chip ecosystem that took Taiwan three decades to build, according to Jason Hsu, a former legislator in Taiwan and now a research fellow at Harvard Kennedy School with a focus on semiconductors and geopolitics. It would be easier to leave the job to its Asian allies. “You don’t need to raise a cow to have the milk,” Hsu said. “You just have to make sure that the milk can be delivered to your doorstep.”

On February 24, 2024, TSMC inaugurated its newest factory, located in Kumamoto, Japan, where construction had begun about a year later than in Arizona.

At the ribbon-cutting ceremony, guests were served Taiwan’s signature pineapple cakes and greeted by the beloved bear mascot Kumamon. Thanks to strong government support, local partnerships, and a low-cost labor force that worked 24/7, the factory had been completed at dazzling speed.

“We committed to getting it ready in two years because that’s what TSMC asked us,” Kumamoto Governor Ikuo Kabashima told Bloomberg. Chang hailed the factory as the start of “a renaissance of semiconductor manufacturing” in Japan.

Although the factory in Japan will make less-advanced chips than the American one, the news out of Kumamoto prompted feelings of envy in Phoenix. There, engineers felt that they were falling even further behind.

The same weekend as the opening of the Japanese plant, Taiwanese engineers discussed the struggle of working with Americans at a gathering in Phoenix. “The Japan factory opened first. I’m very frustrated,” a Taiwanese engineer said.

Sitting in a room together, the engineers admitted that although they had made some progress in acclimating to life in the U.S., TSMC had yet to find a balance between the two work cultures. Some Taiwanese workers complained that management was being too accommodating in giving Americans less work, paying them high salaries, and letting them get off work early.

Another engineer said the company babied Americans. “If local hires are not ready, this is our opportunity to apply for a green card,” he joked.

Another engineer said he sometimes shared the Americans’ frustration with the hierarchy, discipline, and long hours. But these things, he believed, had enabled TSMC to surpass its competitors to become the chip leader.

“Everything comes from working hard. Without this culture, TSMC cannot be number one in the world,” he said with passion. “I want to support TSMC to be great. It’s my religion.”