Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news on fascinating discoveries, scientific advancements and more.

CNN

—

For nearly two centuries, scientists have tried to solve an enduring mystery about a giant millipede-like animal named Arthropleura that used its many legs to roam Earth more than 300 million years ago.

Now, two well-preserved fossils of the creature unearthed in France have finally revealed what Arthropleura’s head looked like, providing insights into how the giant arthropod lived.

Today, arthropods are a group that includes insects, crustaceans, arachnids such as spiders, and their relatives — and the extinct Arthropleura remains the largest known arthropod ever to live on the planet.

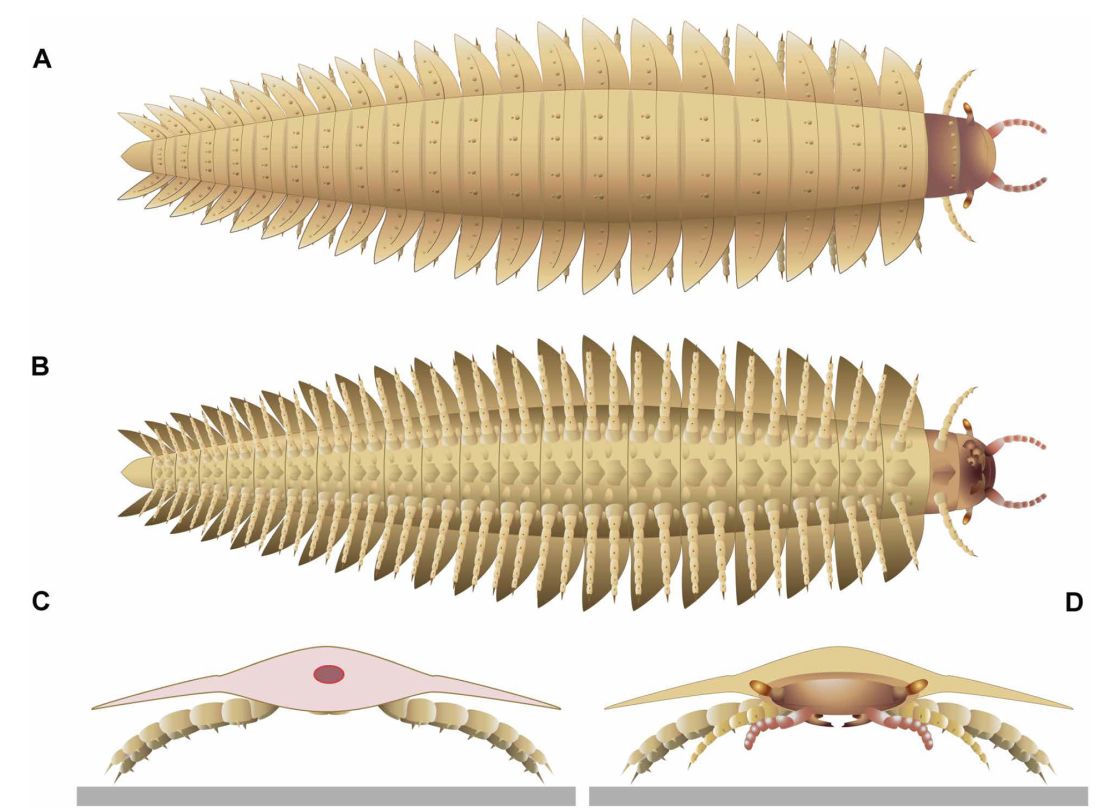

Scientists in Great Britain first found fossils of Arthropleura in 1854, with some adult specimens reaching 8.5 feet (2.6 meters) long. But none of the fossils included a head, which would help researchers determine key details about the creature, such as whether it was a predator similar to centipedes or an animal that merely fed off decaying organic material like millipedes.

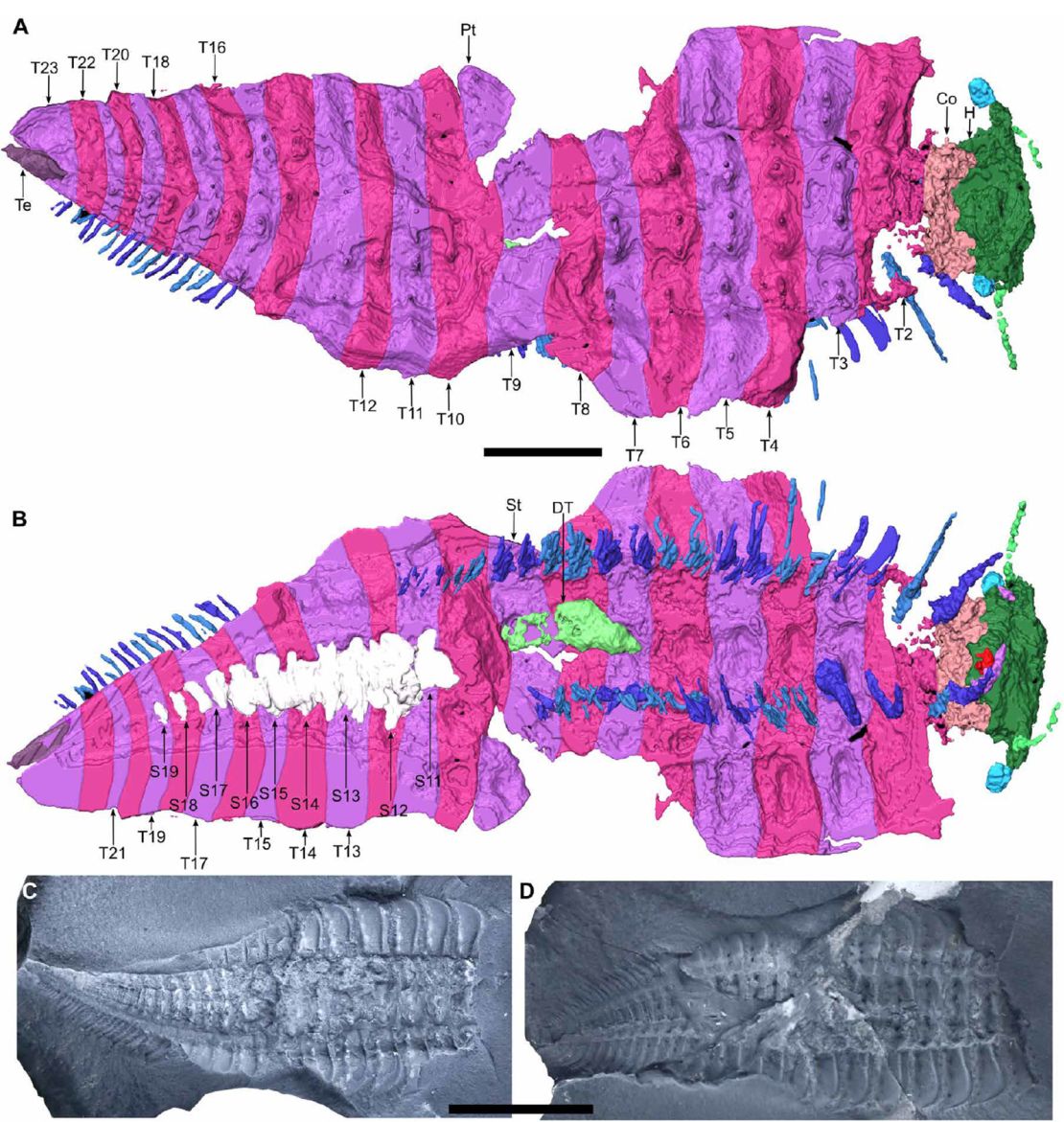

In a quest to find the first complete head, researchers conducted an analysis of Arthropleura fossils belonging to two juvenile individuals uncovered in the 1970s in France. The findings were published October 9 in the journal Science Advances.

The odd tale of Arthropleura gained a new twist when the study team scanned the fossils, which are still trapped in stone.

The head of each animal showcases characteristics belonging to both millipedes and centipedes, which suggests that the two types of arthropods are more closely related than previously believed, according to the study authors.

“By combining the best available data from hundreds of genes from living species in this study, alongside the physical characteristics that allow us to place fossils like Arthropleura on evolutionary trees, we’ve managed to square this circle. Millipedes and centipedes are actually each other’s closest relative,” said study coauthor and paleontologist Dr. Greg Edgecombe, an expert in ancient invertebrates at London’s Natural History Museum, in a statement.

From the fossils and treadlike tracks Arthropleura left behind, scientists determined that the massive creature lived between 290 million and 346 million years ago in what’s now North America and Europe — and it was just one of many giants roaming the planet.

An abundance of atmospheric oxygen caused creatures such as scorpions and now-extinct dragonfly-like insects called griffinflies to reach enormous sizes that dwarf their modern counterparts, the study authors said. But Arthropleura still stood out, reaching about the same length as modern alligators, lead study author Mickaël Lhéritier said.

Lhéritier is pursuing his doctorate in ancient myriapods, an arthropod group that includes millipedes and centipedes, at France’s Claude Bernard University Lyon 1 to understand how arthropods adapted to live on land millions of years ago.

Once the animals died and became buried in layers of sediment over time, some of them became entombed in a mineral known as siderite, which solidified and formed a nodule around the remains. Becoming encased in stone helped preserve even the most delicate aspects of the fossilized creatures.

Such nodules were first spotted at a coal mine in Montceau-les-Mines, France, in the 1970s and then were transferred to French museum collections.

“Traditionally, we’d split open the nodules and take casts of the specimens,” Edgecombe said. “These days, we can investigate them with scans. We used a combination of microCT (micro-computed tomography) and synchrotron imagery to examine the Arthropleura inside, revealing the fine details of its anatomy.”

The 3D scans revealed two nearly complete specimens of Arthropleura that lived 300 million years ago. Both fossilized animals still had most of their legs, and one of them had a complete head, including antennae, eyes, mandibles and its feeding apparatus — the first Arthropleura head ever documented, Lhéritier said.

The team was surprised to uncover that Arthrorpleura had body characteristics seen in modern millipedes, such as two pairs of legs per body segments, as well as the head characteristics of early centipedes, such as the positioning of its mandibles and shape of its feeding apparatus. The creature also had stalked eyes, like crustaceans, Lhéritier said.

In addition to helping researchers better understand what Arthropleura looked like, the discovery also draws a closer evolutionary connection between modern millipedes and centipedes.

Previously, scientists thought the two arthropods had a more distant relationship, but in recent years, genetic studies have shown that millipedes and centipedes were more closely related.

“This new scenario was (criticized) on the fact that there was no ‘fossil’ or anatomical argument to defend this grouping, but our new findings on Arthropleura that combine features of both groups tend to confirm this new scenario,” Lhéritier wrote in an email.

Researchers believe the two Arthropleura fossils belonged to juveniles because they reach just 0.9 inch (25 millimeters) and 1.5 inches (40 millimeters) long.

Studies of Arthropleura specimens have shown that the animals vary in the amount of body segments they have, similar to most millipedes that add body segments until they reach a fixed maximum. But centipedes have all their body segments already in place at birth, according to the study authors.

This finding suggests that Arthropleura attained peak segmentation as an adult, rather than at birth. But the researchers are curious to determine whether they found true juvenile specimens, or a previously unknown smaller species, as well as the growth rate over time for such an animal.

“Tracks found elsewhere in Montceau-les-Mines suggest that these Arthropleura were probably around 40 centimeters (1.3 feet) at their longest,” Edgecombe said. “While there’s nothing to say that they couldn’t be bigger, we don’t currently have any evidence of this.”

What Arthropleura ate and other mysteries

Now that researchers have uncovered a complete Arthropleura head, they hope the discovery can help them solve other riddles about the giant animal, including what it ate and how it breathed. But other fossils that preserve additional aspects of the arthropod’s body, including the head of an adult, will need to be found.

“While definite gut contents are yet to be found, other details of these fossils contribute to the debate over Arthropleura’s diet,” Edgecombe said. “They don’t have any venom fangs or legs (specialized) for catching prey, suggesting it probably wasn’t a predator. As its legs are better suited for slow movement, they were probably more like the detritus-eating millipedes alive today.”

Lhéritier, who is studying another group of ancient myriapods that may have been amphibious, said he is curious about Arthropleura’s stalked eyes.

“Today, stalked eyes are a typical feature of aquatic arthropods like crabs or shrimps,” he said. “Could it mean that Arthropleura could have been amphibious? To answer this, we need to find the respiratory system of Arthropleura. Finding these organs can help us (understand) the link of Arthropleura with water. Gills like crustaceans would mean an aquatic/amphibious lifestyle while tracheae (like insects or other myriapods) or lungs (like spiders) would mean a terrestrial lifestyle.”

But unraveling what Arthropleura’s head looks like solves a key mystery, said James C. Lamsdell, associate professor of geology at West Virginia University in a related article that appeared in Science Advances. Lamsdell was not involved in the new study.

“(These) remarkable findings, based on two almost complete juvenile individuals, present a new view of this enigmatic arthropod,” Lamsdell wrote.

“(T)he most exciting discovery comes from the specimens’ heads that bear a mosaic of millipede and centipede characteristics. … As the mystery of the affinities of the largest known arthropod is laid to rest, the work of reconstructing the life history of this exceptional creature can finally begin.”