Infra

Protecting Critical Infrastructure with Reusable Respirators Caches

To help protect U.S. critical infrastructure workers from future pandemics and other biological threats, the next presidential administration should use the federal government’s grantmaking power to ensure ample supplies of high-quality respiratory personal protective equipment (PPE). The administration can take five concrete actions:

- The Office of Pandemic Preparedness and Response Policy (OPPR) can coordinate requirements for federal agencies and recipients of federal emergency/disaster preparedness funding to maintain access to at least one reusable respirator per critical employee.

- The Department of Labor’s Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) can initiate an occupational safety rule on reusable respirator resilience caches.

- The Department of Health and Human Services’ Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response (ASPR) can require PPE manufacturers receiving federal funding to demonstrate their robustness to extreme pandemics.

- ASPR’s Strategic National Stockpile can start stockpiling reusable respirators.

- The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) can leverage its public outreach experience to increase “peacetime” adoption of reusable respirators.

These actions would complete the Biden Administration’s existing portfolio of efforts to reduce the likelihood of dangerous PPE shortages in the future, reaffirming executive commitment to protecting vulnerable workers, building a resilient national supply chain, and encouraging innovation.

Challenge and Opportunity

The next pandemic could strike at any time, and our PPE supply chain is not ready. Experts predict that the chance of a severe natural epidemic could perhaps triple in the next few decades, and advances in synthetic biology are increasing the risk of deliberate biological threats. As the world witnessed in 2020, disposable PPE can quickly become scarce in a crisis. Inadequate stockpiles left millions of workers with insufficient access to respiratory protection and often higher death rates than the general public—especially the critical infrastructure workers who operate the supply chains for our food, healthcare, public safety, and other essential goods and services. In future pandemics, which could have a 4% to 11%+ chance of occurring in the next 20 years based on historical extrapolations, PPE shortages could cause unnecessary infections, deaths, and burnout among critical infrastructure workers.

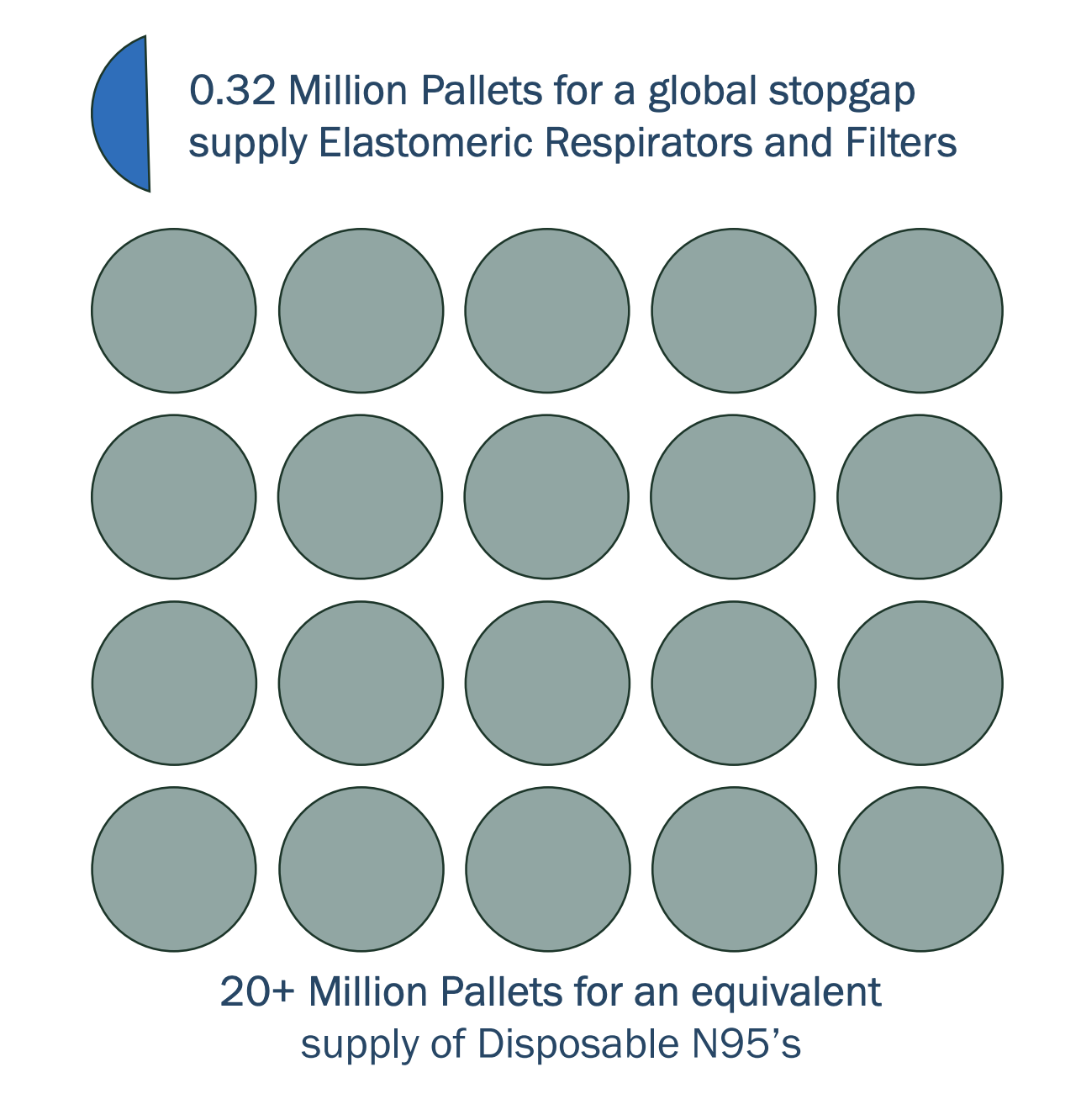

Figure 1. Notional figure from Blueprint Biosecurity’s Next-Gen PPE Blueprint demonstrating the need for stockpiling PPE in advance of future pandemics.

Recognizing the vulnerability of our PPE supply chain to future pandemics, Section 3.3 of the National Biodefense Strategy and Implementation Plan directs the federal government to:

Establish resilient and scalable supply and manufacturing capabilities for PPE in the United States that can: (a) enable a containment response for; and (b) meet U.S. peak projected demand for healthcare and other essential critical infrastructure workers during a nationally or internationally significant biological incident.

At a high level, securing the supply of PPE during crises is already understood as a national priority. However, despite the federal government’s past efforts to invest in domestic PPE manufacturing, production capacity will still take time to ramp up in future scenarios. Our current stockpiles aren’t large enough to bridge that gap. Some illustrative math: there are approximately 50 million essential workers in the United States, but as of 2022 our Strategic National Stockpile only had about 540 million disposable N95 respirators. This is barely enough to last 10 days, assuming each worker only uses one per day. (One per day is even a stretch: extended use and reuse of disposable N95s often leads to air leakage around wearers’ faces.) State- and local-level stockpiles may help, but many states have already started jettisoning their PPE stocks as purchases from 2020 expire and the prudence of paying for storage becomes less visible. PPE shortages may happen again.

Fortunately, there is existing technology that can reduce the likelihood of shortages while also protecting workers better and reducing costs: reusable respirators, like elastomeric half-mask respirators (EHMRs).

A single EHMR typically costs between $20 and $40. While the up-front cost of an EHMR is higher than the ~$1 cost of a disposable N95, a single EHMR can reliably last a worker for thousands of shifts over the entirety of a pandemic. Compared to disposable N95s, EHMRs are also better at protecting workers from infection, and workers prefer them to disposable N95s in risky environments. EHMR facepieces often have a 10-year shelf life, and filter cartridges typically have the same five-year shelf life of a typical disposable N95. A supply of EHMRs also takes up an estimated 1.5% of the warehouse space of the equivalent supply of disposable N95s.

Figure 2. The relative size of equivalent PPE stockpiles. Source: Blueprint Biosecurity’s Next-Gen PPE Blueprint.

Some previous drawbacks of EHMRs were their lack of filtration for exhaled air and the unclear efficacy of disinfecting them between uses. Both of those problems are on their way to being solved. The newest generation of EHMRs on the market (products like the Dentec Comfort-Air Nx and the ElastoMaskPro) provide filtration on both inhalation and exhalation, and initial results from ongoing studies presented by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) have demonstrated that they can be safely disinfected. (Product links are for illustrative purposes, not endorsement.)

Establishing stable demand for the newest generation of EHMRs could drive additional innovation in product design or material use. This innovation could further reduce worker infection rates by eliminating the need for respirator fit testing, improving comfort and communication, and enabling self-disinfection. It could also increase the number of critical infrastructure workers coverable with a fixed stockpile budget by increasing shelf lives and reducing cost per unit. Making reusable respirators more protective, ergonomic, and storable would improve the number of lives they are able to save in future pandemics while lowering costs. For further information on EHMRs, the National Academies has published studies that explore the benefits of reusable respirators.

The next administration, led by the new OPPR can require critical infrastructure operators that receive federal emergency/disaster preparedness funding to maintain resilience caches of at least one reusable respirator per critical infrastructure worker in their workplaces—enough to protect those workers during future pandemics.

These resilience caches would have two key benefits:

- Because many U.S. critical infrastructure operators, from healthcare to electricity providers, receive federal emergency preparedness funds, these requirements would bolster our nation’s mission-critical functions against pandemics or other inhalation hazards like wildfire smoke. At the same time, the requirements would be tied to a source of funding that could be used to meet them.

- By creating large, sustainable private-sector demand for domestic respirators, these requirements would help substantially grow the domestic industrial base for PPE manufacturing, without relying on future warm-basing payments like those that Congress recently rescinded.

By taking action, the next administration has an opportunity to reduce the future burden on taxpayers and the federal government, help keep workers safe, and increase the robustness of domestic critical infrastructure.

Plan of Action

Recommendation 1. Require federal agencies and recipients of federal emergency/disaster preparedness funding to maintain access to at least one reusable respirator per critical employee.

OPPR can coordinate a process to define the minimum target product profile of reusable respirators that employers must procure. To incentivize continual respirator innovation, OPPR’s process can regularly raise the minimum performance standards of PPE in these resilience caches. These standards could be published alongside regular PPE demand forecasts. As products expire every 5 or 10 years, employers would be required to procure the new, higher standard.

OPPR can also convene representatives from each agency that administers emergency/disaster preparedness funding programs to critical infrastructure sectors and can align those agencies on language for:

- Requiring funding recipients to maintain access to resilience caches of enough PPE.

- Explicitly including “maintaining access to PPE resilience caches” as an acceptable and encouraged use of funding.

The Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) within the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) can update its definition of essential workers and set guidelines for which employees would need a reusable respirator.

FEMA’s Office of National Continuity Programs can recommend reusable respirator stocks for critical staff at federal departments and agencies, and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) can also set a requirement for healthcare facilities as a condition of participation for receiving Medicare reimbursement.

Recommendation 2. Initiate an occupational safety rule on reusable respirator resilience caches.

To cover any critical infrastructure workplaces that are not affected by the requirements in Recommendation 1, OSHA can also require employers to maintain these resilience caches. This provision could be incorporated into a broader rule on pandemic preparedness, as a former OSHA director has suggested.

OSHA should also develop preemptive guidance on the scenarios in which it would likely relax its other rules. In normal times, employers are usually required to implement a full, costly Respiratory Protection Program (RPP) whenever they hand an employee an EHMR. An RPP typically includes complex, time-consuming steps like medical evaluations that may impede PPE access in crises. OSHA already has experience relaxing RPP rules in pandemics, and preemptive guidance on when those rules might be relaxed in the future would help employers better understand possible regulations around using their resilience caches.

Recommendation 3. Require PPE manufacturers receiving federal funding to demonstrate their robustness to extreme pandemics.

The DHS pandemic response plan notes that workplace absenteeism rates during extreme pandemics are projected to be to 40%.

U.S. PPE manufacturers supported by federal industrial base expansion programs, such as the investments managed by ASPR, should be required to demonstrate that they can remain operational in extreme conditions in order to continue receiving funding.

To demonstrate their pandemic preparedness, these manufacturers should have:

- An on-site stockpile of enough reusable respirators for the maximum number of workers they might hire during a manufacturing surge.

- A comprehensive pandemic response plan that addresses workplace transmission protection.

- Regular exercises and independent evaluations of their pandemic response plans.

Recommendation 4. Start stockpiling reusable respirators in the Strategic National Stockpile.

Inside ASPR, the Strategic National Stockpile should ensure that the majority of its new PPE purchases are for reusable respirators, not disposable N95s. The stockpile can also encourage further innovation by making advance market commitments for next-generation reusable respirators.

Recommendation 5. Leverage FEMA’s public outreach experience to increase “peacetime” adoption of reusable respirators.

To complement work on growing reusable respirator stockpiles and hardening manufacturing, FEMA can also help familiarize the workforce with these products in advance of a crisis. FEMA can use Ready.gov to encourage the general public to adopt reusable respirators in household emergency preparedness kits. It can also develop partnerships with professional groups like the American Industrial Hygiene Association (AIHA) or the Association for Health Care Resource & Materials Management (AHRMM) to introduce workers to reusable respirators and instruct them in their use cases during both business as usual and crises.

Conclusion

Given the high and growing risk of another pandemic, ensuring that we have an ample supply of highly protective respiratory PPE should be a national priority. With new reusable respirators hitting the market, the momentum around pandemic preparedness after the COVID-19 pandemic, and a clear opportunity to reaffirm prior commitments, the time is ripe for the next administration to make sure our workers are safe the next time a pandemic strikes.

This action-ready policy memo is part of Day One 2025 — our effort to bring forward bold policy ideas, grounded in science and evidence, that can tackle the country’s biggest challenges and bring us closer to the prosperous, equitable and safe future that we all hope for whoever takes office in 2025 and beyond.

Are critical infrastructure workers interested in using reusable respirators?

read more

Will these requirements increase costs for employers?

Not in the long run. As a single employee infection can cost $340 per day, it is more cost-effective for most employers to spend around $3 per critical employee per year for reusable respirators. For hospitals in states like California or New York, which mandate one- to three-month PPE stockpiles, switching those stockpiles to reusable respirators would likely be cost-saving, as demonstrated by past case studies. Most of these hospitals are still meeting those requirements with disposable N95s largely because of slow product choice re-evaluation cycles.

Managing these resilience caches would also pose a minimal burden on employers. Most EHMRs can be comfortably stored in most indoor workplaces, taking up around the volume of a large coffee mug for each employee. Small workplaces with fewer than 50 employees could likely fit their entire resilience cache in a cardboard box in a back closet, and large workplaces will likely already have systems for managing emergency products that expire, like AEDs, first-aid kits, and fire extinguishers. As with other consumables like printer ink cartridges, PPE manufacturers can send reminders to employers when the products they purchased are about to expire.

To put this into perspective, fire alarm units should generally be replaced every 10 years for $20 to $30 each, and typically require new batteries once or twice per year. We readily accept the burden and minor cost of fire alarm maintenance, even though all U.S. fire deaths in the last 10 years only accumulate to 3% of COVID-19’s U.S. death toll.

read more

What about workers who can’t wear EHMRs?

While EHMRs fit most workers, there may be some workers who aren’t able to wear them due to religious norms or assistive devices.

Those workers can instead wear another type of reusable respirator, powered air-purifying respirators (PAPRs). While PAPRs are even more effective at keeping workers safe than EHMRs, they cost significantly more and can be very loud. Employers and government stockpiles can include a small amount of PAPRs for those workers who can’t wear EHMRs, and can encourage eventual cost reductions and user-experience improvements with advance market commitments and incremental increases in procurement standards.

read more

Aren’t physical stockpiles inefficient?

Yes, but they reduce the risk of any lags in PPE access. Every day that workers are exposed to pathogens without adequate PPE, their likelihood of infection goes up. Any unnecessary exposures speed the spread of the pandemic. Also, PPE manufacturing ramp-up could be slowed by employee absences due to infection or caring for infected loved ones.

To accommodate some employers’ reluctance to build physical stockpiles, the administration can enable employers to satisfy the resilience cache requirement in multiple ways, such as:

- On-site resilience caches in their workplaces

- Agreements with distributors to manage resilience cache inventory as a rotating supply bubble

- Agreements with third-party resilience cache managers

- Purchase options with manufacturers that have demonstrated enough capacity to rapidly manufacture resilience cache inventory at the start of a pandemic

Purchase options would function like a “virtual” resilience cache: they would incentivize manufacturers to build extra warm-base surge capacity and test their ability to rapidly ramp up manufacturing pace. However, it would increase the risk that workers will be exposed to infectious disease hazards before their PPE arrives. (Especially in the case of a severe pandemic, where logistics systems could get disrupted.)

read more

Would these resilience caches be usable for any other hazards besides pandemics?

Yes. Employers could use respirators from their resilience cache to protect workers from localized incidents like seasonal flu outbreaks, wildfires, or smog days, and put them back into storage when they’re no longer needed.

read more

Could this be expanded to other pandemic hardening activities, beyond PPE?

Yes. Federal emergency/disaster preparedness funding could be tied to other requirements, like:

- Installing the capacity to turn up workplace air ventilation or filtration significantly

- Maintaining and regularly exercising pandemic response protocols

- Investing in passive transmission suppression technology (e.g., germicidal ultraviolet light)

read more

How might these requirements affect post-emergency PPE spending?

The next time there’s a pandemic, having these requirements in place could help ensure that any post-emergency funding (e.g., Hazard Mitigation Assistance Program grants) will be spent on innovative PPE that aligns with the federal government’s broader PPE supply chain strategies.

If the Strategic National Stockpile receives additional post-emergency funding from Congress, it could also align its purchases with the target product profiles that critical infrastructure operators are already procuring to.

read more

)