World

How Thomas Merton both loved and kept his distance from the world | Aeon Essays

In 2014, feeling prematurely jaded at just 29, I planned a two-week ‘digital fast’, hoping to cure my weariness and professional despair. I’d worked as a freelance writer for startups, think tanks and business schools, producing mindless content in the name of ‘thought leadership’ and I’d grown embarrassed to contribute to a world in which ‘creative’ had become a noun, ‘journal’ a ponderous verb, and where Arianna Huffington’s recent book Thrive was taken for gospel. Still, it paid, and the perk was that I could work from anywhere, like one of those ‘digital nomads’ I had read about in the media, with their self-improvement manuals and minimalist aesthetic.

My own escape was fairly mild: I borrowed a friend’s studio flat in Hong Kong, where I’d finished my last underwhelming freelance job, and used it as a resting place. An urbanite’s monastic cell at 200 square feet, the unit was a short walk from the Hong Kong Central Library, where I went daily, with my notebook and thermos of Nescafé. I was desperate to reform myself. I had always wanted to write, but wasn’t exactly sure why, and recently my notebooks had begun filling with characters and literary images instead of ideas for articles. It seemed important to understand the nature of this impulse: was it passion or ambition? I had read the philosopher Byung-Chul Han’s The Burnout Society (2010), and accepted that I was a hopeless ‘achievement-subject’ like the rest of my peers, chasing money and grants and degrees. For purity’s sake, I’d need to retreat, to ‘unplug’ and ‘go off the grid’, to pursue what Han and others have called the vita contemplativa.

Hong Kong; March, 2011. Photo by Stefan Lins/Flickr

But how? The need to unplug had already been coopted by an unrelenting corporate wellness industry, with its call to ‘redefine success’ and create a life of ‘wellbeing, wisdom and wonder’, to quote from the movement’s prophet-in-chief, the aforementioned Huffington. Then I spotted a creased and faded paperback copy of The Asian Journal of Thomas Merton (1968) on the shelf of a used bookstore along Hennessy Road. I hesitated, then bought the book.

Merton had been important to me in my teenage years, ever since a priest had recommended him as the apotheosis of poetic sensibility: a Catholic monk and social critic, he’d used his imagination well by drawing himself closer to God. Though I wasn’t sure about God, I loved Merton’s sensibility, his warmth, his raw theology. But I worried that he wouldn’t hold up to the scrutiny of adult malaise, that his spiritual writing might betray a fatal innocence. I had recently braved a tragic reunion with Aldous Huxley, who’d failed the test – his journey proving how easily the path of Western mystic leads to the castle of psychedelics or a bungalow in the Hollywood Hills. Merton was the more serious pilgrim. He corresponded with Thich Nhat Hanh and D T Suzuki on the principles, methods and challenges of Buddhist meditation at a time when Huxley and others were more interested in LSD. Merton studied Islamic scholarship. He read Sufi poetry with a seriousness that set him apart from the Western beatnik. He’d joined a Trappist monastery in rural Kentucky, where he lived for 27 years in admirable solitude. Still, I knew executives who quoted Merton in PowerPoints on inspiration and leadership, and I feared his Journal might fall into the Westerner-travels-to-Asia-to-find-himself genre, which was overrepresented in the bookshops of Hong Kong. In the end, curiosity won out, and I spent several days immersed in Merton’s journey of 1968.

In one sense, his Journal offers a portrait of postcolonial Asia at the height of the global counterculture and antiwar movements. It begins in October, with Father Merton thousands of feet in the air, on a Pan American flight from San Francisco to Honolulu, with continuing service to Bangkok, where his grand tour would begin. After Bangkok, he would visit Calcutta, New Delhi, Dharamsala, Madras, Colombo and Singapore, where he’d meet with fellow devotees of the contemplative life, including a 33-year-old Dalai Lama. Then he’d return to Bangkok for a conference, where he’d give a talk called ‘Marxism and Monastic Perspectives’. The Vietnam War was raging, with 500,000 US troops stationed throughout the country, and the hippy movement was drifting east in search of bearded gurus.

He’s a thorn in the robes of the Trappists for his waywardness, his tendency to break with orthodoxy

Yet the Journal is also a vivid account of spiritual longing and restlessness, just the thing for a disillusioned achievement-monger unconvinced by the bromides of corporate mindfulness. (Twitter’s co-founder Jack Dorsey, for example, once returned from a silent retreat in Myanmar, leading his employees to believe such meditative practices were an ideal self-optimisation tool.) Merton’s goal, by contrast, was to ‘drink from ancient sources of monastic vision’ to deepen his own spiritual commitments. He wasn’t there to recharge; he was there to achieve enlightenment and offer himself as an agent of peace. At the same time, he’s trying to write – the journal is strewn with lecture notes, poems and scraps of essays – and there’s a fascinating tension in his dual role as writer and monk, his enduring need to orchestrate his enlightenment and describe it, too. It’s part of what makes him fun to read: even as he’s cultivating a more serene consciousness in Thailand or India, he’s anxious about his future at the Abbey of Gethsemani, where he’d lived since 1941.

Merton had reason to be anxious. Over two and a half decades at Gethsemani, he wrote and published a bestselling autobiography, The Seven Storey Mountain (1948), as well as a handful of other popular books. By 1968, however, his reputation was attracting visitors, and his solitude was under threat. That winter, after the Beatles flew to India to meditate at Maharishi’s ashram, Life magazine called 1968 ‘the year of the guru’. Merton doesn’t want to be a guru, not necessarily. He considers seeking a new home in Alaska or California, where he might find renewed peace. But he also likes the attention, and we know from other journals that he’s struggled of late to honour his vows. In 1966, he fell in love with a young Kentucky nurse (an episode Merton scholars have pruriently debated: was the relationship platonic or not?) Ever since, he’s been a thorn in the robes of the Trappist authorities for his waywardness, his tendency to break with orthodoxy. Is he planning to leave the Trappists for the Buddhists? That seems possible. In Tokyo, he drinks a glass of whisky at the airport bar and broods on troubles large and small. He’s anxious about the Vietnam War, the student protests, Herbert Marcuse, the sad cultural hegemony of a superficial America, and the fact that Nixon is poised to win the upcoming election. Also, he’s been charged for overweight baggage, having bought too many books in San Francisco before the journey.

Prose-wise, the Journal is a slow burn, and I worried that Merton – famous, authoritative – would offer only the platitudes and tourist clichés of a ‘thought leader’. ‘The Pacific is very blue,’ he writes in the first entry, possibly one of the most boring sentences ever recorded. Fortunately, it gets better. Further down the page, he offers delicate portraits of his seatmates and the airline staff; the delay on the tarmac in San Francisco is ‘the slow ballet of big tailfins in the sun’, and at the ‘ecstatic’ moment of take-off, there’s ‘the dewy wing’ covered with ‘rivers of cold sweat running backward’. His plane tilts thrillingly over the Golden Gate Bridge and the gleaming coast. ‘May I not come back without having settled the great affair,’ he writes to himself in that first entry. ‘And found also the great compassion …’ Suspense is part of the Journal’s appeal. Will he settle the great affair? Will he find the great compassion?

I confess I was sceptical. ‘Compassion’ is just another handsome word, after all, like ‘mindfulness’. But Merton imbues the term with a reverence I found difficult to ignore. He calls it mahakaruna, invoking the Buddhist ideal of selflessness, where the barrier between ourselves and others is porous and malleable. My version of this was literary: I read novels and memoirs to experience that porousness. As a writer, though, I wondered: was there a necessary relationship between writing and compassion?

Merton’s own writing is suffused with the sorrow of his personal dilemma: his ambivalence over whether to escape the world or engage with it; the tension between his longing for community and also solitude. He reads Siddhartha, Rumi’s poems, and geopolitical bulletins – the questions that deserve the most attention. Competing with that sorrow is his clear aptitude for delight: his way of thinking prayerfully and bemusedly at the same time. When a soldier heading for Vietnam laughs at a joke in the Reader’s Digest, Merton notes the dissonance between his childish humour and the solemn fate that awaits him, and thinks: ‘God protect him.’ In Bangkok, he chats with a bhikku, or monk, on the Thai Buddhist concept of sila (‘control of outgoing exuberance’) which Merton links to the Javanese concept of rasa, and hopes to cultivate in himself. But the world is always beckoning. In Calcutta, he writes to Lawrence Ferlinghetti, then to the Queen of Bhutan. He reads the papers – every section, even the horoscopes. Octavio Paz resigns as ambassador to India. In Greece, Jackie Kennedy marries Aristotle Onassis. Tito threatens a third world war if Russia invades Yugoslavia. And, of course, he himself is news. Life magazine takes his photo ‘worshiping’ under a banyan tree in Narendrapur, which he finds awkward, all too aware of what the monks back home at Gethsemani will think. At a conference, he’s approached by two hippies wearing miniskirts and a swami who ‘gives an irresistible impression of Groucho Marx’. The absurdity of modern life is granted surprising pathos. ‘Stocks are up in … Hong Kong,’ he writes, ‘and the astronauts have colds.’

The gauzier parts of Merton are simply too easy to fold into the corporate wellness industry or pop gurudom

This raw warmth and playfulness will endear Merton to some readers more than The Seven Storey Mountain, an autobiography whose style is hamstrung by Merton’s need to justify his submission to Catholic order. Not that there’s nothing of note in his discovery of literature at Cambridge and Columbia (including his time on staff at Jester, Columbia’s student humour magazine) or his fondness for his English professor Mark Van Doren. But all his favourite writers and teachers, it turns out, are simply part of the Lord’s choreography. ‘I think my love for William Blake had something in it of God’s grace,’ he writes. Something in it? The link sounds forced. Mountain reads like the memoir of a senator with a checkered past: cheesy, vague, propagandistic.

In the crucial scene, he’s reading the letters of Gerard Manley Hopkins when he drops the book, walks nine blocks to the corner of Broadway and 121st, and announces that he’d like to accept God. Who did he pass along the way? What kind of sounds did he hear? We don’t know. So confident is the author in the drama of his conversion that the prose falls depressingly flat. (‘What scales of dark night,’ he writes, ‘were peeling off my intellect!’) A more sceptical contemporary reader longs for the frostier prose of Evelyn Waugh or the acid wit of Walker Percy’s satire Lost in the Cosmos. The gauzier parts of Merton are simply too easy to fold into the corporate wellness industry or pop gurudom, even Christian apologetics.

My experience of the Asian Journal could not have been more different. There’s genuine drama in Merton’s fascination with Buddhism and in his reading of Karl Marx at the height of the Cold War. And Merton the writer – that shadow self who’d followed him into the cloister – was in evidence on every page, describing the world without needing to offer an ecumenical frame, sneaking jokes and poems and songs and doodles past the censor. I was glad to see how well preserved his imagination was, how attuned his ear for irony, how sharp his literary eye. He observes the rosy light, the kites and the domes of New Delhi with an artist’s sense of gratitude. In Calcutta, he watches a young girl sprinting after his taxi fall behind ‘as if she were sinking in water’. He likes the temples and ashrams, but he likes the sound of a goatherd’s flute on the road to Dharamsala more, and he’s struck by the marigolds growing in tins cans along the path that leads to the Namgyal Monastery. He meets a 10-year-old boy, whom he notices ‘rolling down his sleeves to be more ceremonious’ and notes, in the more sardonic mode of Percy or Waugh, the comically martial exhortations of India’s Christian pamphleteers (‘God has declared state of emergency. BE HOLY NOW!’). It’s the kind of humour that loves life. When he’s offered a print of a mandala as a tool for meditation, he decides the method is not for him: ‘On close inspection I find it to be full of copulation.’ From his hotel in New Delhi, he can see the Chinese embassy. ‘What do they know in there? What do they do? … Is one of them secretly writing a poem?’

Time and again, Merton returns to the question of just how contemplative a contemplative life should be. He’s impressed by the Dalai Lama’s youthful energy and compassion, but concerned he might be too removed from modern life and global events; he gives the lamas copies of Time and Life magazines to ‘catch up’. But he also knows that an active life is useless without the resources that contemplation offers, including self-understanding, integrity and the capacity to love. In Singapore, that most ‘worldly’ of cities, he has the kind of exchange you’d expect, chatting about Marx and the Zhuangzi with a local college professor: but having grown up as an expat in that thoroughly corporate city-state, I had to laugh at how easily impressed he was by its cleanliness, diversity and charm.

Merton’s interest in Marx ran deep, and here one sees the theme of his Bangkok lecture start to click into gear. Both communists and monastics seek to avoid alienation, he thinks, which is obviously a Marxist idea but also one that St Paul addressed at the dawn of the Christian Church. For Merton, a monk is someone who says that ‘the claims of the world are fraudulent’ and who demonstrates the necessary transformation of consciousness through meditative practices. Both he and the Dalai Lama wish they had more time to meditate, to live a fully monastic life – to avoid, as Merton caustically puts it, the ‘blue-haired ladies in pants’ and the ‘rich people who have nothing better to do’. He posits a ‘dialectic’ between ‘world refusal’ and ‘world acceptance’, drawing inspiration from the Madhyamika school within Mahayana Buddhism.

As I sat in my own private pool of light on the top floor of that library in Hong Kong, I could feel this pesky dialectic buzzing within myself, and was grateful to see it put into words. As I understood it, the goal of this school, sometimes called the ‘Middle Way’, was to ‘deconceptualise’ the mind and dissolve all ‘notions’. I was fine with this. I didn’t like my notions that much anyway. If I had to choose a path for myself, it might as well be the Middle Way, which ‘does not deny the real’ only ‘doctrines about the real’. I accepted this, too, as a statement about the writing life. Focus on the real, not the doctrines about the real, I thought. I wouldn’t put it this way now, but the notion hasn’t completely dissolved.

He feels uncomfortable in his monastic habit while riding on trains; he’d rather wear a turtleneck and corduroy pants, like the poet he was

I think what I was looking for in Merton’s Asian Journal was permission to withdraw into the monastery of literature. It was certainly more feasible than joining the Trappists or Jesuits, though of course there are other strategies. As an expat, I could appreciate a figure like T S Eliot, who had actually studied Buddhist texts at Harvard before he morphed into an Anglo-Catholic royalist, annulling his low status as a native son of Missouri. For Thomas Mann, the answer was a Swiss sanitorium, and then the Pacific Palisades. For D H Lawrence, Oaxaca and Taos. I’d heard that Rainer Maria Rilke, as a young man, had tried to become Russian, even going so far as to wear a peasant’s blouse and muddle his German, which is goofy and hilarious, though not unrelatable. Katherine Mansfield ran away from Wellington high society at 19 and went around conducting doomed affairs. Jack Kerouac had sex and booze and the mythopoetic confidence of a true amphetamine junky. Unfairly, I thought of Merton’s dramatic conversion as a strategy along this same continuum: he needed divine sanction for his autobiographical urge: his love for sitting in quiet rooms. I understood the appeal, of course. As Franz Kafka put it, a writer needs more solitude than the world can give – ‘even night is not night enough.’

But wasn’t it selfish to sit in a quiet room, given the state of the world? Wasn’t that ‘quietism’, and wasn’t quietism a heresy? Merton didn’t think so, and he doesn’t exactly ignore the events of 1968 – in fact, he’s thinking about them constantly. His trip to Calcutta coincides with a riot led by Maoist students, who burn an effigy of the US Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara to express support for the North Vietnamese. In Madras, he reflects on the crime of imperial war, including the East India Company’s war against the Moguls; and he has a long discussion with a fellow spiritual leader about the difference between aesthetic and religious experience.

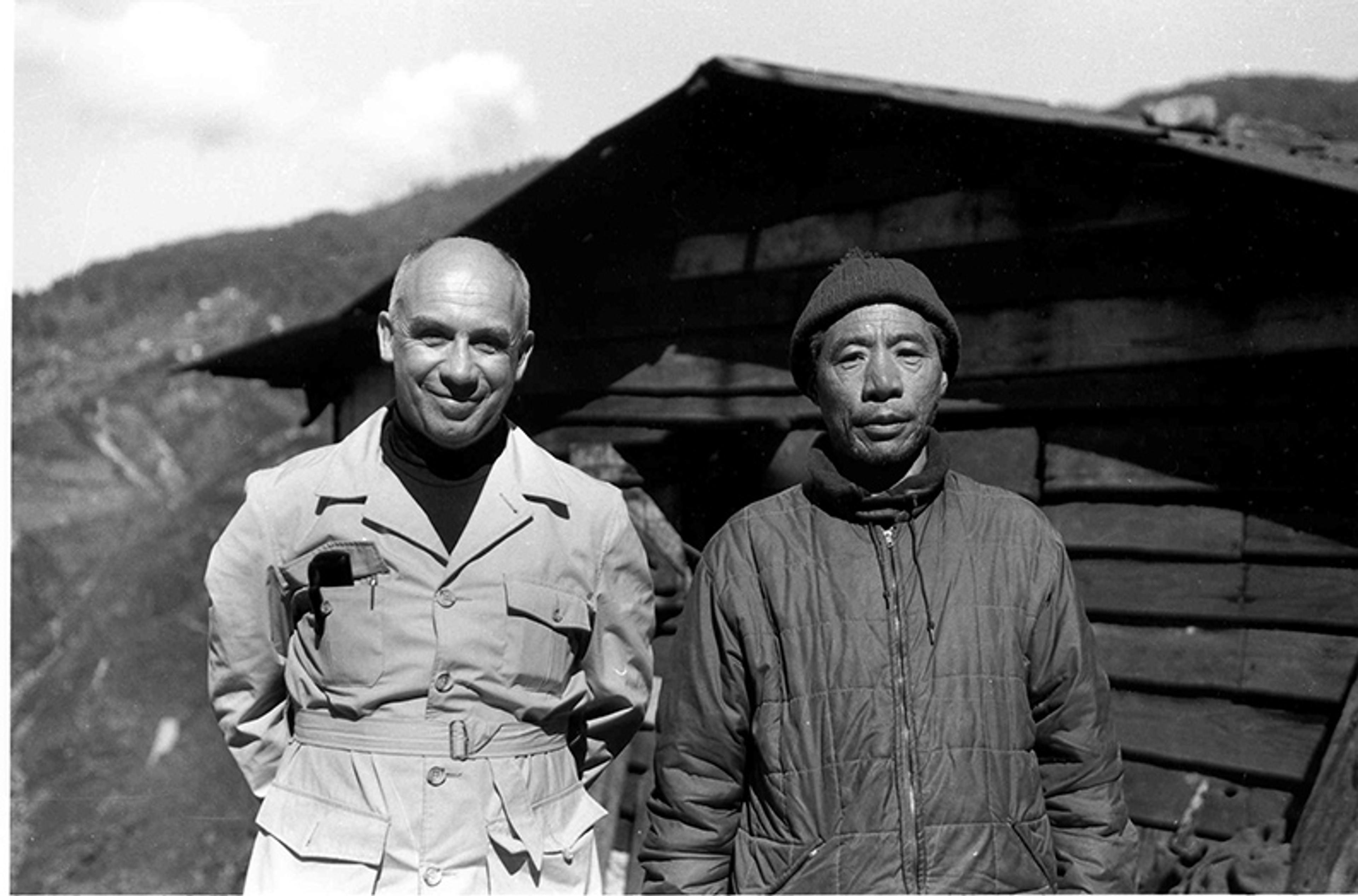

Thomas Merton and Chatral Rinpoche. Used with permission of the Merton Legacy Trust and the Thomas Merton Center at Bellarmine University

Still, enlightenment is on his mind. When he meets the Tibetan Buddhist Dzogchen master Chatral Rinpoche, they agree to achieve Buddhahood together, as a kind of pact (‘in our next life, perhaps even in this life’). Privately, he’s less sure and, later on, he chides himself: ‘Too much movement. Too much “looking for” something: an answer, a vision.’ He feels uncomfortable wearing his monastic habit while riding on trains; he’d rather wear a turtleneck and corduroy pants, like the poet he was. He thinks about California again, with its redwoods and its ocean, but he dreams about Alaska. Should he settle there? Is the dream a sign? Can he find a deeper solitude? What if he left Gethsemani, with its social obligations, and spent more time perfecting his own spiritual long division? What if he simply disappeared?

The problem is, he has postcards to send – to the poet Czeslaw Milosz; to his brothers and sisters back in Kentucky. He’s filled with love, but he’s not sure how to exercise or ration that love. In the mountains above Darjeeling, he reflects on a passage by Edward Conze, a scholar of Marx and Buddhism. ‘True love requires contact with the truth,’ Conze writes, ‘and the truth must be found in solitude.’ Riding the Kandy Express through Ceylon, he’s moved by the sight of boys and girls washing their clothes and balancing like gymnasts on the train tracks – a tourist cliché, he knows, but also an indisputable vision of joy. For weeks, he’s been reflecting on what Buddhists call avidya, the ignorance that comes from placing the ego at the centre of life. To overcome this ignorance is to perceive existence as ‘gift and grace’, but he knows from years of monastic strife that this requires discipline. Merton wonders if he’s detached enough from the world. Or is he too detached? If only he could find the perfect setting for his solitude. If only he could learn how to escape the world and heal it, too. Maybe then he would finally achieve ‘the great compassion’.

It’s a problem Merton never solved, because he died a few weeks later in a freak electrical accident. After Ceylon, he had returned to Bangkok for a conference, where he delivered his final public address, ‘Marxism and Monastic Perspectives’, to a group of Catholic monks at a Red Cross facility. He’d returned to his cottage for a shower and some downtime, and while barefoot on the terrazzo floor – this is what the authorities guess – he reached for a large standing fan and was shocked with 220 volts. His body was found an hour later by two monks who shared his cabin. The fan, still running, lay across his chest, a puddle of blood by his ear. His colleagues delivered a blessing before he was taken to the US Air Force Base, from where he was flown home in the company of American soldiers killed in Vietnam.

Catholics, including the Jesuit priest who first suggested Merton to me, tend to read his Asian Journal as the record of a monk who achieved interfaith enlightenment before he died. And it’s true that while in Ceylon he had a profound experience at Gal Vihara, the so-called ‘rock temple’, where four giant sculptures of Buddha were carved into a single rock, back in the 12th century:

I am able to approach the Buddhas barefoot and undisturbed, my feet in wet grass, wet sand. Then the silence of the extraordinary faces. The great smiles. Huge and yet subtle. Filled with every possibility, questioning nothing, knowing everything, rejecting nothing, the peace not of emotional resignation but of Madhyamika, of sunyata, that has seen through every question without trying to discredit anyone or anything – without refutation – without establishing some other argument. For the doctrinaire, the mind that needs well-established positions, such peace, such silence, can be frightening. I was knocked over with a rush of relief and thankfulness at the obvious clarity of the figures, the clarity and fluidity of shape and line, the design of the monumental bodies composed into the rock shape and landscape, figure, rock and tree … Looking at these figures I was suddenly, almost forcibly, jerked clean out of the habitual, half-tied vision of things, and inner clearness, clarity, as if exploding from the rocks themselves, became evident and obvious.

A moving scene, especially given how close he was to the end of life. But it’s not the part I returned to most while hunched within my cubicle in the Hong Kong Central Library. Instead, I found myself pausing over a passage I’d overlooked at first. The ‘contemplative life’, he writes:

should create a new experience of time, not as stopgap, stillness, but as ‘temps vierge’ … a space which can enjoy its own potentialities and hopes, and its own presence to itself. One’s own time. But not dominated by one’s own ego and its demands. Hence open to others – compassionate time, rooted in the sense of common illusion and in criticism of it.

‘Compassionate time’ – I liked that phrase. It reminded me of the poet Osip Mandelstam’s manifesto, which I’d read in college as part of a course in modern Russian poetry. Love … your own existence more than yourself, I’d copied into my journal, thinking what a useful motto for an artist prone to self-disgust. Had Merton ever read that line? It seemed to express the basic move of the kind of writer I wanted to be, and I sensed that Merton was after something similar in his Trappist way. For Merton, the goal of monastic life was not to embrace solitude for its own sake. Monks were aloof, but they weren’t antisocial. The point was to learn to live by love – to translate, in Augustinian terms, cupiditas into caritas, or self-centred love into other-centred love. The rimpoches in the Himalayas were saying much the same thing. Solitude was a means through which one sought the great compassion.

The journey was inward, as Merton knew, despite his evident wanderlust

This idea became foundational to my writing life that month, and it changed the way I thought about my weathered spiral notebook, which I now viewed, in a nod to Merton’s spirit, as my ‘journal’. This journal would not be a bleak Calvinist ledger of moral accounting, as it once was for Benjamin Franklin, or a productivity tool, as it now was for ‘work smarter’ guys like Tim Ferriss and Cal Newport, or a means of indulging the saccharine tenets of popular cognitive therapies. No, my journal would be the portal through which I accessed ‘compassionate time’. I didn’t need a monastery. All I needed were notebooks and a relatively quiet place – night enough, I said to myself.

For the rest of that month, though I kept up with pro-democracy protests and the drift of global politics, I perched at a desk in the Hong Kong Central Library – my Walden Pond, my desert ranch, my abbey of Gethsemani – and wrote the kind of sentences that no respectable thought leader would ever care to purchase. I didn’t need to become a ‘global nomad’ or a ‘creative’. What I needed was a secret realm and a vast tract of compassionate time. A wild Daoist garden on my otherwise Confucian estate. The journey was inward, as Merton knew, despite his evident wanderlust, and it didn’t matter whether you were dressed in robes or corduroys. What mattered was that you sustained your imagination through a lifetime with a monk’s joyous discipline – an impossible task, and a worthy one.

For Montaigne, the writer moves away from the crowd to ‘repossess’ himself. But part of me always hoped to be possessed by something not myself: a voice, a mood, a character, a sentence, a line, a beautiful image, something transcendental that would wrench me from the daily buzz that Martin Heidegger calls ‘the forgetting of Being’. To love one’s own existence means to embrace the fact that one is merely a conduit of energies, a node in the great bureaucracy of universal consciousness, a brief and very lucky guest. As Hermann Hesse – whom Merton read – writes in his novel Demian (1919): ‘[E]very man is more than just himself; he also represents the unique, the very special and always significant and remarkable point at which the world’s phenomena intersect, only once in this way and never again.’ If I could learn to perceive the world closely and magnanimously, to preserve my imagination through the storms and droughts of daily life, I’d have my own vision to offer, my own testimony. To put this in less exalted terms, I had learned, at the age of 29, what a writer’s journal was actually for.

Until this reencounter with Merton, I thought I would need to conduct my own fraught writerly pilgrimage, as Gideon Lewis-Kraus does in his memoir A Sense of Direction (2012), or as Geoff Dyer does in his book on D H Lawrence, Out of Sheer Rage (2014). Instead, I sat in the library and wrote down what I felt and saw: the curtain of rain that shuddered across the faded cement of Victoria Park; the teenage couple kissing in the glass elevator as it dropped from mezzanine to ground floor; the woman directly in front of me, playing Candy Crush on her phone. My contemporaries, I thought to myself, including the wet trees and the rain, which was now pirouetting over a distant highway overpass.

By the end of his life, Merton believed in the interdependence of all things. A Buddhist cliché, but I finally understood where he was coming from. The compassion I felt was mine but also not mine, is all I can say. At the end of the month, I flew to Chicago, choosing to embrace my fate as a struggling fiction writer and teacher. I bid Merton adieu; I would live my life in corduroys. But at least I had learned what writing was: it was disciplined compassion. On the plane, I watched the slow ballet of tailfins, and the dewy wing, and I felt enormous affection for my seatmates, even the noisy one. I wrote in my journal for hours. I napped. When I woke up, we were still over water, 200 miles south of Alaska. He’s right. The Pacific is very blue.