Fashion

Faith in fashion: Formerly homeless student finds footing as first-gen graduate – El Camino College The Union

Her sister Nadia Mendoza tried to fling herself out of the passenger door as the gray Nissan sedan hurtled down the 605 Freeway at 110 mph. Nadia thrashed as her family members tried to stop her from grabbing the door handle.

The four other passengers in the car — their mother Maria Mendoza, Ashley Mendoza, her other sister Iris Mendoza and Nadia’s son Anthony — struggled to restrain Nadia. She was stronger than all of them.

Nadia let out a blood-curdling growl. Her face, covered in tears, snot and sweat, contorted in a fit of rage, her eyes crazed and scared at the same time.

“She was speaking different languages,” Ashley said. “She was stronger than my dad and my brother put together.”

They were on their way to an exorcism, in hopes that Nadia would be freed from the demons that the whole family believed had been possessing her for four months.

Ashley was 12. She didn’t know it then, but this episode was part of a series of events that would lead her to a career in fashion years later. She’d win multiple awards at El Camino College. And she would become the first in her family to graduate from college despite eight months of living out of her car, homeless.

***

Ashley, 32, was born in San Bernardino County, the youngest of nine children. She was born 15 years after her parents, Jose and Maria Mendoza, crossed the border in 1977 with five children in tow.

Upon arriving in San Bernardino, Jose made a living selling leather bags and shoes and women’s clothing, some of which he sewed himself.

It didn’t take long for Jose and Maria, both 28 at the time, to find a house. Business was good enough to sustain the family. Jose hired his brother and other relatives to work for him at his home-based sewing business.

Four more children later, Jose gradually lost the business. His relatives owed him money that he told the children years later he was never repaid. The family lost the house and had to stay with Jose’s brother in San Bernardino.

One day, when Ashley was 3, her mother dressed her up in her Sunday best. Her parents told her and her siblings that the three of them — father, mother and Ashley — were going to the store.

They never came back. They went to the airport and back to Mexico, leaving eight of Ashley’s siblings with her uncle in San Bernardino.

A year later, while Ashley was still in Mexico with her parents, their uncle and his wife told four of her other siblings, ages 5 to 16, that they were going on a field trip. They were also being hauled back to Mexico, while the eldest four remained in San Bernardino.

“They put us all in a plane. We didn’t know what was going on. We flew alone, not knowing what to do,” Wendy Sufle, one of Ashley’s sisters who was 9 at the time, said.

The Mendozas – Jose and Maria with their five youngest children – returned to California that same year and reunited with the four eldest siblings in San Bernardino. They eventually rented a two-bedroom house in Compton where the 11 of them lived under one roof.

***

Ashley had her first beer when she was 5. She was thirsty and it was the only thing in the fridge. She thought it was refreshing, like soda. She thought drinking beer was normal, like drinking juice.

Her father was never the same when he came back from Mexico. He turned to drinking. It started with one or two bottles of beer for a nightcap until it got worse.

“There were points where they would call us from the bar and be like, ‘Come pick up your dad. He’s lying outside on the pavement. He’s too drunk. He can’t go home. Can you pick him up?’” Wendy said.

Her mother and older sisters would go look for her father at 3 a.m. to bring him home.

“He didn’t realize that it was hurting us, watching him,” Wendy said.

He was never violent with their mother or any of the children but his drinking problem got to the point that he would buy beer instead of groceries.

“I remember being drunk a lot of the times and crying in the corner and feeling like no one loved me,” Ashley said.

Ashley struggled with mental health issues as an adult. She worked at the L.A. County Library in Compton but had to leave her job because of depression and anxiety.

“I couldn’t even sit at my desk without crying. A lot of the times I had to get up, go to the bathroom and cry,” she said.

***

There was blood everywhere.

It was 4 a.m. and the police had come again. Broken fragments of plates and glasses were strewn all over the floor. Ashley’s brother and his girlfriend had been fighting the whole night, and at one point it looked like they were about to kill each other, Ashley said. The neighbors called the police on them. Again.

Ashley was 9. She was in third grade and she was held back that year.

“Every morning we’d get waken up by cops at like 4 or 5 in the morning, and we couldn’t leave the house until they left,” Ashley said.

The police would leave around 7 or 8 a.m.

“I didn’t want to go to school late, so I would just stay home,” she said.

***

The demons would come at midnight.

“That was the time that she would get possessed, at night,” Wendy said.

Ashley said the first time it happened she saw her sister Nadia on the floor, shaking like she was having a seizure.

“It’s a crazy story. I feel like most people wouldn’t believe,” Ashley said. “It was almost like the movie, ‘The Exorcist.’”

They wanted to call the paramedics but her mother said it wasn’t a seizure. They rushed Nadia to every Catholic church they could find. Ashley said no church wanted to help them.

“They just said, ‘Oh, that’s just like the ancient times. That doesn’t happen anymore,’” she said.

They decided to help her at home. Nadia would be herself during the day but would change dramatically at night.

“We would sleep in the daytime and at night we would stay up. Everyone would be watching,” Ashley said.

They would gather the children in one of the rooms with the door that had a good lock. They would keep watch the whole night. Nadia would be convulsing on the floor and speaking in tongues, foam coming out of her mouth. She was stronger than all of them.

“They couldn’t hold her down,” Ashley said.

***

Nadia used to “cleanse her with an egg.” She was 11. Nadia would hold up an egg all over Ashley’s body and break the egg into a glass. They would check the colors of the egg. Black meant bad energy.

The family believes Nadia was possessed because she practiced witchcraft and black magic. She used a Ouija board. The sisters believe their mother had a “gift” which was passed down from generations to Nadia.

“So there are people who were taught and people who are born naturally with it. And (Nadia) was born – and we were also born with it,” Wendy said.

They said people in the U.S. don’t believe in this but it’s “a normal, popular thing in Mexico.”

When Catholic churches didn’t help them, they went to a Jehovah’s Witness parish. While there, a woman overheard Maria explaining the situation to the church leaders. The woman, who didn’t want the church leaders to know she had visions, set her mother aside and told her she saw one. In the vision she saw the names of the streets, the time, place and event where God told her He would meet the Mendoza family and take all the demons from Nadia.

They went to an event of the Las Buenas Nuevas church at an open field at Excelsior High School in Norwalk. Nadia resisted all the way there and tried to throw herself out of the car.

When they got there, the pastor asked the crowd to raise their hand if they wanted to be prayed over.

“My sister at the time, she was like herself in that instant and she raised her hand and said, ‘Me, help me!’” Ashley said.

It was short-lived.

“That’s when she didn’t look like herself again. They ordered people to take her into a tent,” Ashley said.

The pastor and other church leaders prayed for her sister for four hours starting at 8 p.m. By midnight, Nadia was herself again. The episodes stopped.

“So after all that happened, the whole house was changed, like overnight, because of God,” Ashley said.

Her father stopped drinking.

“When my sister’s demons were gone, he never touched alcohol again. He stopped cold turkey,” Ashley said.

***

Ashley hated school. She didn’t see education as important. All she wanted was to finish high school and help her father support the family. She had Ds and Fs at Dominguez High School.

“Living in Compton, it’s more like a ghetto area, so it’s like, we get paid less attention,” she said.

Her brother was in a gang and she thought that life was cool.

But her sister Dinora took her to a church event in downtown L.A. right after she graduated from high school in 2014.

“That’s when I had prayed and I asked God, ‘What should I do?’ Because I graduated and I was lost,” she said.

She was torn between fashion and culinary, or whether to pursue a college degree at all.

“I didn’t know which direction to take. And so that’s when…I said that in my mind, ” Ashley said.

Everyone had been prayed for by the pastor except her. She was the last one.

When the pastor came, she told Ashley, “God said fashion. He’s gonna use you in fashion.”

Ashley was surprised because the pastor was a stranger and no one heard what she prayed for. At the same time, she wasn’t surprised because of all the things they went through with her sister and their spirituality.

That’s when she went into fashion with everything she had. She enrolled at El Camino College.

***

The Korean-made Sunstar sewing machine at the Mendoza family’s garage in Compton is 23 years old. Jose bought it brand new in 2001 for $300 at the Bega & Son Sewing Machine Center in downtown L.A.

The 75-year-old Jose always had a passion for sewing. He had 15 brothers and sisters. He never went to school and he learned how to help with the family’s finances at 5 years old in Mexico. He worked at a shoemaker’s store where he swept the floor. The shoemaker eventually let him help make the shoes.

In time, he learned how to sew clothes and dresses to match the shoes. When he started dating his wife Maria, he made her dresses and matching shoes. He did the same for his children.

“He never left us without clothes and shoes,” Wendy said. “I remember asking him, ‘How did you meet my mother?’ And he said, ‘Well, I was the one who would go to their house and do their shoes as well as their clothes.’”

When they moved to the U.S., they couldn’t find pants that would fit the 4-foot, 4-inch Maria. Everything was too long. He repaired all her pants to make them fit.

Ashley loved hearing this story as a child. She didn’t know that she could make her own clothes. When she realized she could, she started cutting up her clothes.

“My mom would always get mad at me because she’d be like, ‘I just bought you that shirt.’ And I’m like, ‘Yeah, but I want to make it different.’”

Her siblings wanted to throw the sewing machine out to make room in the garage but Ashley put her foot down and said no. She still uses it for her projects.

It belongs to her now.

***

Ashley could feel someone’s eyes on her. She opened her eyes and saw a man leaning over, taking a peek inside the car, staring at her.

She woke up in a cold sweat.

It’s a recurring nightmare. She has not recovered since it happened.

She moved out of the Compton house because she said she was in constant fights with her siblings.

She and her boyfriend Antonio Guzman lived in her red Prius with untinted windows and broken A/C in February 2020.

Ashley had become a statistic.

In a 2021 campus climate survey, 8% of El Camino students said they did not know where they were going to spend the night at least once during the past year.

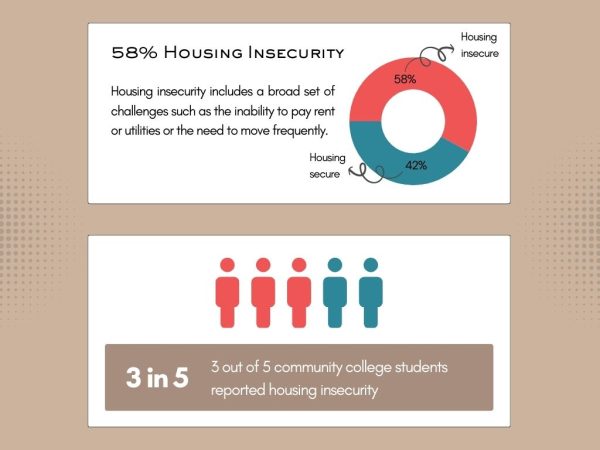

A 2023 basic needs survey at 88 California community colleges said 58% of the over 66,000 student respondents experienced housing insecurity in the previous 12 months.

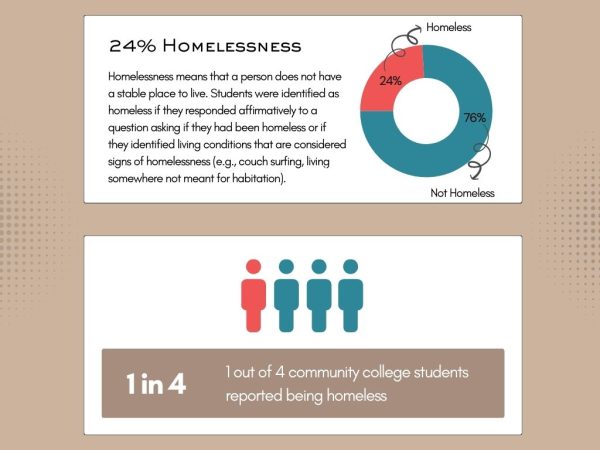

The survey from the California Community College Office also said 24% of students experienced homelessness in the previous 12 months.

One in four community college students reported being homeless.

Ashley was one of them.

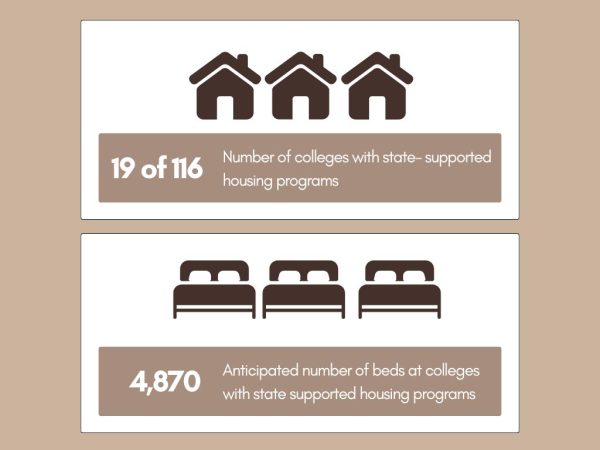

Sharonda Barksdale, student success coordinator of the Basic Needs Center at El Camino, said L.A. County has different programs that address homelessness depending on the student’s age. Students 22 years old and below are considered “youth” and are referred to a youth program or agency in the area.

Ashley was 27, not married and belonged to the “single adult” category when she was homeless.

“If they are single adults — I try and be very honest, open and honest — there are not a lot of options,” Barksdale said. “Even referring them to our lead agency in the area, the resources are going to be very limited, and you know, very close to nothing,” she said.

Guzman, 22, is an El Camino political science graduate who was finishing his degree at UCLA.

They bought a tent to cover the car after they caught a man peering over them as they slept while parked on a street in Lawndale.

Ashley said they were hungry all the time because they had no money for food. She delivered food for DoorDash.

“We had to choose between eating or having money for gas so we could keep doing DoorDash,” she said.

She parked in the McDonald’s parking lot in Lawndale to use the free WiFi for assignments. Her laptop, which she borrowed from the Schauerman Library, kept getting disconnected from WiFi every 30 minutes, sometimes during exams. The WiFi hotspot that she also borrowed from the library broke down completely.

They parked in public parks to sleep at night but the police who patrolled the area told them they couldn’t sleep in the car.

“Sometimes the cop would be like, ‘If we come around here and you’re sleeping in your car, we’re going to arrest you guys.’”

So they drove to different locations throughout the night, from Gardena to Torrance to Lawndale.

They signed up for a Planet Fitness membership in Torrance to shower before heading to class and work. They went to public restrooms when they didn’t have money for the monthly gym fee.

Some restrooms had locks. She would ask cashiers for the code and said she would order after using the restroom. When she was done, she ran as fast as she could while the cashier wasn’t looking.

The most difficult was when she had her periods or when she had an upset stomach.

“That would be the worst, because it’s like, I don’t have time to run to the bathroom. And, you know, sometimes it would…just come out, like, on our sheet, so I got to throw it away,” she said.

Ashley felt that was the last straw. She told her mother about her situation. Her mother didn’t know she was living in her car – she thought all along that her daughter was staying with a friend. Her mother asked her to move back home.

***

The air was thick with anticipation. The two-hour-long fashion show on June 3 had wrapped up. The audience at the packed Haag Recital Hall had been treated to an evening of style, showcasing the talents of the El Camino Fashion Department students. There was an evening gown that glowed, an entire collection made of denim and reimagined business suits.

The judges had made their decision.

“And the best collection, for ‘Medieval Summer,’ Ashley Mendoza!”

The 5-foot, 4-inch tall designer in a strapless, tight-fitting long black dress sashayed the length of the stage to claim her plaque to thunderous applause. Her long black hair was gathered in a bun on top of her head, wavy tendrils framing both sides of her fully made-up face. Her long eyelashes fluttered as she held back tears.

Ashley at 31 was a picture of sophistication as she thanked her family and her four models in a short speech. The win meant more to her than the audience realized. It was a coronation to 10 years of hard work. That’s how long it took her to finish her fashion design and merchandising degree at El Camino College, part of which was spent being homeless for eight months.

It took her 10 years because of financial and mental health struggles.

She almost didn’t make it to this fashion show because she didn’t have the funds for the materials. She only finished one design the week before the show. She told Guzman she was no longer doing it.

Guzman also had limited funds. His car payment was coming up.

“I was like, I could pay my car payment, or I could give her the little bit that I had to be able to help her,” Guzman said. “I ended up losing my car, it got repoed, but I was able to help her with the fashion show.”

Guzman also helped her with the idea for “Medieval Summer.” The collection was inspired by medieval armor. She said her life “felt like going to war every day trying to survive all the adversities” thrown her way. She used leather, metal chains and a mesh chainmail fabric.

Ashley was grateful for her victories. Earlier that month, she learned she got accepted to the internship she applied for. She interned at Forever 21 as a designer assistant in the summer.

Before the internship was over, she got a call from Torrid, a women’s clothing chain that specializes in plus-size cocktail dresses, jeans, lingerie and footwear.

An El Camino graduate on the Torrid advisory board sent an email to fashion professor Vera Ashley saying she wanted to promote new students and if the professor knew any that would fit the position.

“So I remembered Ashley…how well she did, and it sounded like what she was describing to me. It sounds like the same duties as [Ashley] just finished. So I said, ‘Yeah,’ immediately,” Vera Ashley said.

Ashley started working at Torrid as an assistant technical designer in October.

***

“Ashley’s moving us out of the hood!”

Angel Sufle, Ashley’s 16-year-old nephew, said as he watched his aunt being photographed for Warrior Life in the Mendoza family garage on Oct. 12.

It’s an inside joke, Ashley said. “We live in the ghetto. This city is probably like, one of the most…dangerous, full of gang-related things and all that.”

Though she sometimes lacks belief in herself, she knows her family has faith in her talents. She is still living with her parents, ever since her mother asked her to move back in. But she said the hope is to make it out of Compton.

“They always say, like, ‘Oh, she’s, the one that’s gonna make it out first. she’s gonna take us out of here.’ And…they say, I’m their hope, of giving them a better life,” Ashley said.