Gambling

‘It’s a pure form of gambling’: memecoins boom after Trump election

It is a parable for the attention economy. A celebrity created entirely by social media, “hawk tuah girl” Haliey Welch, helps launch a crypto asset that stokes a viral frenzy and then flames out.

The Hawk memecoin was worth $490m (£385m) hours after it launched on 4 December but now has a market capitalisation – the value of all Hawk coins in circulation – of $17m.

Welch, a Tennessee native who sprang to fame with her response to a risque interview question earlier this year, was immediately accused of ripping off her social media followers. The crypto commentator Stephen Findeisen, who goes by the moniker Coffeezilla, described the launch as a “rug pull” – the term for when developers hype a crypto scheme for short-term gain and then shut down the project.

Hawk is still trading, however, and Welch has said her team “hasn’t sold one token”. Welch’s representatives have been contacted for comment.

The furore has taken place amid a boom in memecoins, which were valued at about $20bn in their entirety at the beginning of the year but are now worth $118bn, according to CoinMarketCap, which monitors crypto prices. And they are flooding the market place in their thousands. At one point in November, the memecoin platform pump.fun launched 69,000 tokens in a day, according to data from the crypto analysis firm Dune.

Experts say memecoins, the latest darling in a crypto field whose true economic worth is endlessly queried, have no fundamental value.

“It’s just a phrase attached to a digital coin. There is no value whatsoever,” says Carol Alexander, a professor of finance at the University of Sussex.

Memecoins riff on two prominent features of the digital economy: memes and cryptocurrencies. The former is an online image or video clip that is endlessly tweaked and recycled on social media to capture the zeitgeist (think Moo Deng the hippo or, more timelessly, distracted boyfriend). A cryptocurrency is a digital asset built on top of a blockchain, a decentralised ledger that tracks the ownership of a cryptocurrency or other digital asset.

Sam Baker, a UK-based memecoin trader, says a lot of the coins’ launches are based on internet trends “you have never even heard of” and rely heavily on influencers to push them on a range of channels from Discord to X and Telegram.

He acknowledges there is “no intrinsic value” in memecoins and there is no “rhyme or reason” to which ones will succeed. Recent launches include coins based on the new Squid Game series on Netflix and on the fall of Bashar al-Assad’s regime in Syria.

“It is a pure form of gambling,” says Baker. “It is like buying a lottery ticket. But some of them are going to rise by 10,000% or 20,000%.”

Memecoins, says Baker, are a merger of two digital economy cornerstones that span different eras of the online boom.

“It’s monetising people’s attention from social media,” he says. “It’s a crossover from web 2.0, which is social media, to web 3.0, which is decentralised finance and crypto. Although they are bonkers, memecoins represent the modern monetisation of the attention economy.”

There is also a link with meme stocks, or shares in publicly listed companies that posted huge gains after being hyped on social media and bought by amateur investors. The classic example is GameStop, a struggling video games retailer that surged in value after a Reddit community piled into the stock.

after newsletter promotion

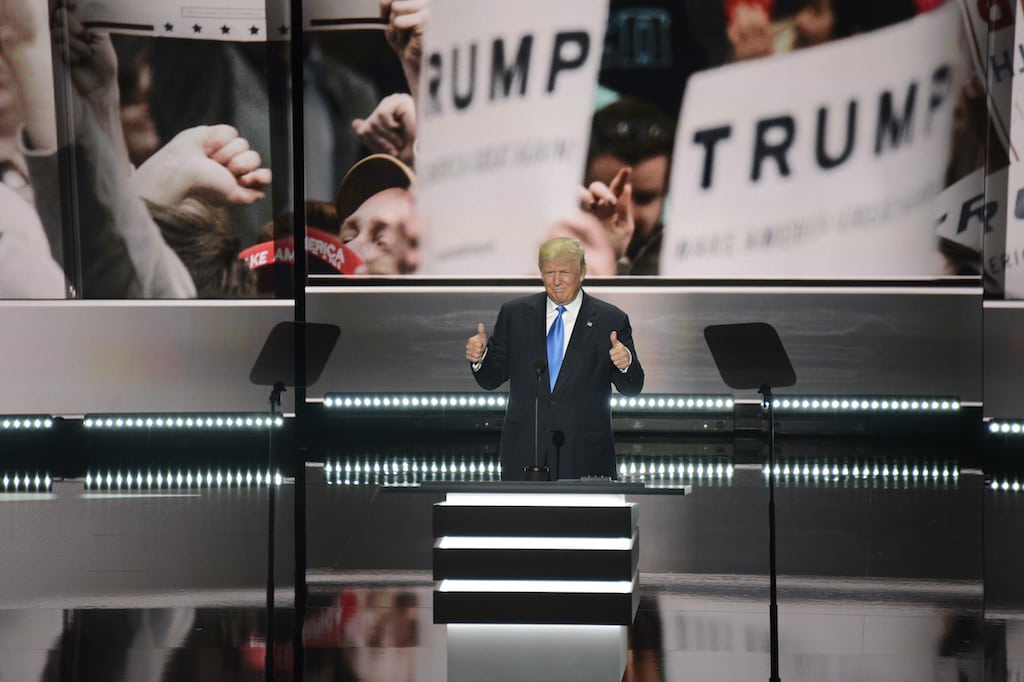

The renewed popularity of memecoins can be traced to Donald Trump’s victory in the US presidential election, with the market doubling in value since his win. Trump is strongly associated with crypto, having pledged during his campaign to end the “persecution” of the industry. Bitcoin, the most valuable digital asset, has been the big beneficiary, with its value crossing $100,0000 for the first time a month after Trump’s win.

Cryptocurrencies appeal to influential figures on America’s political right such as Peter Thiel, the Silicon Valley billionaire, because they eschew the establishment by flying under the radar of regulators and having no underpinning from a central bank. Memecoins are also cheap for retail investors, with many of the tokens costing a fraction of a cent.

Creating them is relatively simple, according to Alexander: just mint, say, $4,000 worth of tokens on a blockchain (Solana is especially popular with memecoin creators) and advertise them across social media, with the hope of selling them at a profit. Once bought, they can also be traded on exchanges.

One of Trump’s key backers, Elon Musk, is a longtime supporter of the first ever memecoin, Dogecoin, based on a meme featuring a shiba inu dog. Launched as a parody of the crypto market, Dogecoin is now worth a more serious $60bn even if its direct use in transactions is limited to a few businesses such as Tesla, where Musk is chief executive.

Merav Ozair, the founder of the Emerging Technologies Mastery consultancy, says Trump’s victory has sparked a new wave of hype around crypto-related assets.

“The new administration promised it would be very pro the crypto space. The new hype is because of the election,” she says.

But, she adds, the basics around memecoins have not changed. “It’s just going to a casino and seeing which number is going to win.”