Jobs

I Had the Most-Hated Job in America. I Was Devastatingly Good at It.

Sign up for The Slatest to get the most insightful analysis, criticism, and advice out there, delivered to your inbox daily.

In my life, I’ve personally witnessed three elite salespeople at work. The first was in the Johnson County, Iowa, jail, where I spent July 4 and 5 some years ago for reasons I’d rather not go into here. It was so overcrowded that we had to sleep head to foot on foam pads, and on the second day, as the discharge process dragged into the afternoon and hangovers set in, the inmates became restive. Among us was a nondescript heavyset guy who started to hold forth: Y’all want to know how to disable a burglar alarm with aluminum foil? Want to know how to cook meth without using fertilizer? Did you know there’s a way to open the door of a squad car from the inside? Soon, almost the entire jail had gathered around him like kindergartners at story time, listening raptly as he dispensed criminal wisdom. Possibly he was making it all up as he went; a guy lying on the floor next to me with his forearm over his eyes would periodically mutter that’s not true, uh-huh, that’s a great way to burn down your house, that kind of thing. But if anything, that only increased my admiration—this guy had installed himself as top dog just by bullshitting.

I know a good salesman when I see one. I was, briefly, the No. 1 telemarketer in the United States. I can’t prove it; this was around 20 years ago, and I haven’t kept any of my framed “top seller” certificates or the daily sales sheets showing me already hitting 350 percent of my weekly quota by Tuesday afternoon. But the company I worked for had one of the biggest telemarketing divisions in the world, and during my hot streak there were several weeks in which I was the top salesperson in the entire company. Believe me or not, but who’d lie about being good at telemarketing? It’s like falsely claiming to have gonorrhea.

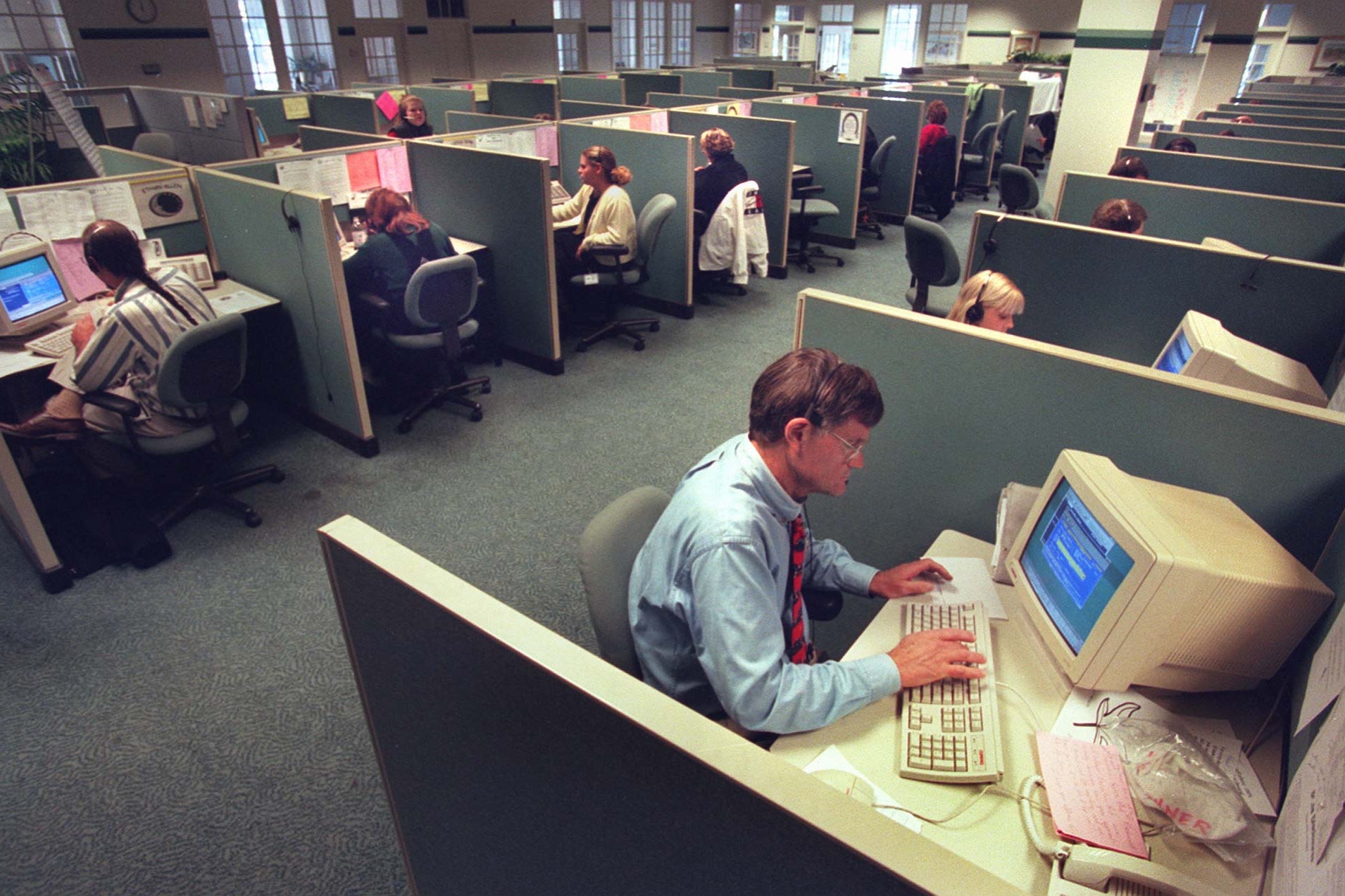

What’s strange is how completely I’d forgotten about this period in my life in the decades since, as one “forgets”—maybe represses is the more accurate word—certain embarrassing exes or haircuts. But it all came back to me recently, when I watched the HBO docuseries Telemarketers. If you’ve ever worked in telemarketing, you’ll immediately recognize the setting: the low-ceilinged, fluorescent-lit office building at the edge of town, the empty liquor bottles piled up in the men’s room, a time capsule of a world that came and went nearly unnoticed. You may even recognize yourself in the grainy VHS footage: an alternative but otherwise identical self, hunched over in an upholstered cubicle, rattling off canned rebuttals to some baffled retiree as you mime the jack-off motion for the amusement of the temporarily bankrupt drug dealer in the next cubicle. It was the Y2K-adjacent midpoint between the door-to-door salesmen of the boomer era and the present-day dystopia of A.I.–enhanced robocalling—the last few years before American credulity (and disposable income) was decisively strip-mined by post–9/11 disillusionment, the emergence of the internet, an economy that seemed to lurch from crisis to crisis, and, well, petty cheats like me, the bedrock of this nation.

I became a telemarketer only because I’d bombed out of every other job in Iowa City, from making the federal minimum wage at a video arcade in Iowa’s largest shopping mall (fired for abusing the “free game” key) to working the graveyard shift at a 24-hour adult video store (fired for being “too horny”). There was unlimited demand for telemarketers in those days; this was in the early aughts, at the tail end of the long-distance wars, when more than 25 million people a year were switching phone companies in pursuit of lower rates on long-distance calls, a sentence that might as well be written in ancient Sumerian to anyone under 30. You didn’t really even have to apply back then. You just put your name in and they told you what day you were starting.

Everyone said that telemarketing was the worst job in town, and for once, everyone was right. Your very first day, you understood that this was the culmination of a long series of bad decisions, the consequences of which you thought you’d escaped—but no, you realized as you walked past the cars in the parking lot with trash bags duct-taped over shattered windows and avoided eye contact with the loiterers in the break room who checked the change slot after you bought a drink from the Coke machine—you’d only put them off until right now. After a short training period that seemed designed mostly to weed out the people who weren’t capable of sitting in a chair for four hours at a time (about half the applicants), we spent some time listening in on the calls of top sellers. I expected them to be devilishly persuasive, modern-day snake charmers, but there didn’t seem to be much to it. They’d tell people they could save them money on their phone bills. If the prospect said they weren’t interested, the seller would either keep talking as if they hadn’t heard or, if a hang-up seemed imminent, recite a “resistance buster” like “I am going to send YOU a check!” The abruptness of this non sequitur, half-shouted over the tail end of the conversation, almost always derailed the lead’s attempts at disengagement, and few people could resist asking, “For how much?”

What do you think? my manager asked after I’d had a few days of listening in on these calls. Could I do it? My entire life savings at the time amounted to a stocking cap about half full of change. I had no choice but to find out.

In the early 2000s, most people were vaguely embarrassed to work in sales—I was—because it evinced need. This was a time when material abundance was such a given that Americans treated it as an entitlement; the gravest insult you could’ve lobbed at someone then was “sellout,” i.e., someone so tactless that they actively pursued success. It was a far cry from today, when we’ve all been stripped of even the pretense of being above the hard sell. In that context, it was only logical that the innate neediness of a sales pitch would be regarded as shameful, almost excremental. Salespeople were by definition losers—if they weren’t, they wouldn’t be asking you for money.

Demand is more like blood, and it has to be mercilessly extracted, drop by drop, by an army of sweaty little goblins who don’t eat unless they hit their quotas.

This was a very novel attitude. Go back a century, when the margins were fat and the marks were plentiful, and sales was a respectable, even aspirational profession, the salesman as romantic and as quintessentially American as the cowboy. If the cowboy limned the frontiers of America, the salesman pacified its inhabitants by converting them into consumers, just as the salesman’s predecessors had converted them into Christians. The first proto-salesmen in America were the roving evangelical preachers, circuit riders who were paid a salary by the church, had monthly sermon quotas, and tracked how many souls they converted. (One definition of evangelize is “to talk about how good you think something is”—to sell, basically.) For pocket money, many of these preachers sold Bibles and books like the Farmer’s Almanac, and in doing so blazed a trail for the secular salesmen who followed, literally, in their footsteps, traveling the same routes, bearing novelty goods like sewing machines, clocks, smut books, and tin scissors.

Many salesmen turned out to be outright cheats, peddling fake spices or canned hams made of wood shavings. Others were a little craftier. According to Birth of a Salesman: The Transformation of Selling in America, by Harvard Business School scholar Walter A. Friedman, a clock salesman, confronted with settlers who swore they had no need for a timepiece, would cunningly ask them to hold a clock for him while he traveled the rest of his route, knowing that when he returned, they’d be unable to live without it. Firms working the lightning-rod grift sent effete dandies to sell farmers on lightning rods for their house, barn, even their outhouse and doghouse, with no money required upfront, but when it was time to collect payment, the salesman was replaced by two or three hulking roughnecks. Book salesmen who met resistance when they returned to settle the bill on preorders were instructed to set up shop at the dining room table and fill out paperwork until money was produced. To keep out “Yankee peddlers,” more than a few municipalities passed laws requiring that out-of-town salesmen buy an expensive license.

But in a very real sense, salesmen built the American economy and, by extension, America itself. In his book, Friedman notes that in the mid-19th century, more than half the U.S. population lived on a farm. Consumer markets were nonexistent. Salesmen went out and made them from scratch, a sale at a time, and not simply by bringing quality goods to eager buyers; they took them by their lapels and didn’t let go until they signed on the dotted line. Fortune magazine observed, in the mid-20th century, “Mass production would be a shadow of what it is today if it had waited for the consumer to make up his mind.” But because of what scholars call “supply-side bias,” we regard 19th-century tycoons like Rockefeller, Carnegie, and Vanderbilt as Übermensch, while erasing the accomplishments of the legions of lowly salesmen. Why? Economists, generally insulated from the dirty realities of turning a buck by tenure and/or wealth, think of demand as a vast natural force to be harnessed, like wind or oil—a conception that fits hand in glove with the equally simplistic “great man” theory, which posits that some people (men) are just born great. Sounds nice, but things look a little less elegant to the salesmen in the trenches. They know: Demand is more like blood, and it has to be mercilessly extracted, drop by drop, by an army of sweaty little goblins who don’t eat unless they hit their quotas. Suddenly, the economy looks more like an infinite series of tiny frauds than a harmonious ecosystem. And if the Greatest Economy in the World is little more than a shill mill, the implications for the Greatest Country in the World are dismaying, to say the least.

Who’s to say? I’m sure one of my betters could produce a little chart proving that the economy is definitely, objectively NOT bullshit, but get a job in sales and you’ll learn the truth by the end of your first week: People don’t buy out of need or desire; they buy because they’ve been sold.

The problem was, I was terrible at selling, at least in the beginning. To be fair, we didn’t have it easy. The telemarketers in Telemarketers were calling for donations to police charities, often (falsely) claiming they were collecting for officers wounded in the line of duty. The burned-out salesmen in the 1969 documentary Salesman, by the Maysles brothers and Charlotte Zwerin, were selling Bibles to people whose names they got from the local parishes, introducing themselves at the door by saying, “I’m here from the church.” If you can’t close those, just hang it up and get a nine-to-five square job. In contrast, I was selling subpar phone service to people who usually had better service already, and who were livid from the moment they realized why I was calling. The majority of the leads hung up in the first three seconds; others stayed on the phone only long enough to detail the sexual acts they’d performed on my mother the previous night. Once, early in my telemarketing days, I called a guy in Colorado who silently listened to my pitch, then asked if I was working out of the Greeley call center. Yes, I lied. “When you get off work tonight,” he said, “I’ll be waiting in the parking lot with a shotgun.”

I couldn’t understand it. I had an airtight pitch and I’d memorized all the rebuttals. But no one was buying. Finally, the manager had me sit in on the calls of one of the call center’s top performers, a soft-spoken divorcée who sat at her corner cubicle and seemed to close sales nonstop, all shift. This was the second elite salesperson I’ve witnessed.

As I remember it, our daily quota was around 3.5 sales in a four-hour shift. The auto-dialer could easily connect you to 100 potential buyers an hour, inclusive of hang-ups and no-answers, meaning you only had to hit a success rate of less than 1 percent. Sounds easy, but most people didn’t come close. Management would let you sit on the phones almost indefinitely without hitting your quotas, but few people could endure this. It was too demoralizing, being a rejection sponge, and, as with waiting tables, the base pay if you made no sales was unlivable. The only way to make real money was to sell, often and consistently. On the quota sheets they gave us, there was a gradated table of commissions; when you hit your weekly quota, you earned a modest bonus, and each sale was worth an additional sum. These sums increased gradually, then exponentially; the first sale after your quota was worth something like $1.10, the 10th was worth $8.50, the 30th was worth $90, and so on.

To reach the higher tiers—a rare feat—you had to get hot and stay hot, every day of the week. For an accomplished salesperson, it was fairly common to have a good day—close five or six or even a dozen sales—but the next day, you’d almost always be back to average or worse. The divorcée, though, was one of the few who could consistently pile up sales so that by Thursday she was making $60, $70, $100 a sale. She was a matronly woman with a kid at home whom we regarded as stuck-up and aloof, though in retrospect this was only because she showed zero interest in smoking ditch weed in the parking lot with us before the shift, or slugging cognac on breaks—she had the temerity to treat her job like a job instead of a temporary diversion before school or jail or some final capitulation that’d land you back in your childhood bedroom. She came in, took her seat, oversize travel mug from home in hand, and sold.

When I shadowed her, I found to my surprise that she was reciting almost word for word the same pitch as everyone else, the same stale rebuttals, but getting much different results. Her warm voice and metronomic cadence had an almost narcotic effect on the leads. Even some of the cranks who snapped at her when they picked up—I don’t want any goddamn phone service, I told the last guy to put me on the no-call list, would meekly backtrack after listening to 20 or 30 seconds of her pitch: I’m sorry, I had a long day at work, what’s this about saving me money? Even I started feeling inclined toward her after a couple of hours. (“Hey, I don’t know if you have plans after work, but I know a place with 10-cent beers between 10 and 11 …”)

Eventually, it clicked, and I learned one of the bedrock principles of salesmanship: Whether you’re peddling long distance over the phone, Bibles door to door, or your own political candidacy on live national TV, it doesn’t matter what you’re selling—it matters how you make people feel. If you make them feel good, they’ll say yes. If you don’t, you could be selling a pill that reverses male-pattern baldness and makes you lose weight without exercise, and they’ll still turn you down flat.

John Ewing/Portland Press Herald via Getty Images

What this entailed for me was basically an attitude adjustment. No one is happy being a telemarketer, no matter how much you’re making, but bad energy will drive away even the easiest money, not only in an Instagram-mysticism law-of-attraction sense, but in the literal sense that Shelly in Wichita is not going to buy what you’re selling, no matter how good the deal is, if she can clearly hear in your voice how much you hate your job and, by extension, her. Grasping this was simple enough, but what was difficult was understanding just how much I had to adjust my sales persona, a realization that really sank in only after a few days of contrasting my halting monotone with the divorcée’s sparkly confidence.

Once I found my sweet spot, though, I started racking up sales. (To this day I can’t talk on the phone without lapsing into my “telemarketer voice,” which sounds like Phil Hartman on ecstasy.) I wasn’t a coaxer, a hand-holder, a persuader; I hit people with my spiel, and if they hesitated or said no, I hung up on them midsentence. On to the next one. Unlike many of my less successful colleagues, I quickly learned to take yes for an answer; though we were legally required to read a long list of mandatory disclosures to all our sales, I noticed that this often broke the spell and gave people an opening to back out or “wait and ask the wife about it.” As soon as I heard a yes, I said, “Great choice!” and transferred them to confirmation. My manager occasionally came by and reminded me that it was technically illegal to skip my disclosures, but he made commission off my commission, and his tone made it clear that I could do as I pleased as long as I kept putting up numbers. Which I did, to an almost ludicrous degree. I hit every kicker, every bonus. I won scented candles, gift cards, and countertop appliances in daily sales contests. I earned the executive parking space in the very front of the lot, even though I took the bus to work. I was pretty pleased with myself. Making $800 in 15 to 20 hours a week when your monthly rent is $300 and beers are a dollar is real wealth.

But it didn’t last.

There’s a scene in Episode 2 of Telemarketers that features a company’s top closer as he works, and we hear him muttering the most evil shit imaginable after being hung up on by old ladies named Joyce and Ethel: I hope your house catches on fire. I hope your neighborhood gets shot up, you stinking bitch. The scene is shot as a horror movie, with a sinister score, but I have to admit I laughed when I saw it. I understood.

Once I started sitting by my fellow top sellers, I noticed that they seemed to enjoy ripping people off. Lying was de rigueur, of course, and rates and plans were fabricated on the spot to close a sale—that’s not what I’m talking about. Instead, leads who begged to be put on the no-call list got vindictively scheduled for Saturday morning callbacks. When a sobbing woman said she couldn’t talk now, her husband was dying, my colleague snapped, Then why’d you answer the phone, Linda? It seemed personal for them.

It didn’t take me long to understand why. We had quotas to meet, and not meeting them could have severe consequences. (As in Glengarry Glen Ross, “first prize is a Cadillac … third prize is you’re fired.”) We badly needed a steady drip of yeses from these people. But the best salesman who ever lived couldn’t close more than 5 to 10 percent of cold calls, which means that the vast majority of everyone you speak to is going to be a no. Eventually, as you’re hung up on, insulted, rejected by hundreds of leads a day, you realize that, miraculously, you have found the architects of your misery: Here, right here—these are the people responsible! The people you’re trying to rip off are simultaneously ripping you off. They are both exploited and exploiters, saviors and enemies. You depend on them, and dependence can only breed contempt.

Fairness, conscience, empathy, and honesty were luxuries that, like caviar or health insurance, were for other people.

So when we promised a lady that we were going to send her a check to “offset” her $75 switching fee (the check was for $1.99), or we told some guy that his master file showed he was already paying 40 cents a minute with the competition (we had no way to know what anyone was paying), and the third-party compliance or a manager cut in on the line and said, Hey, you can’t say that, that’s not legal, we dismissed them as soft, out of touch. Fairness, conscience, empathy, and honesty were luxuries that, like caviar or health insurance, were for other people—we had to work for a living. We were victims. Therefore, we had license to take whatever measures were necessary. Once this worldview sets in, it’s very difficult to break out of, not least because it often feels so perfectly just.

But that’s just the moral alibi. Even worse is the “sales mindset.” Seeing the world through the lens of selling and dealmaking can feel freeing, even empowering, but all you’ve done is condemn yourself to a life of never-ending nickel-and-diming. The better you are at selling, the more debased your life becomes, as everything is reduced to a transaction, a leveraging of the smallest edge: Oh, you didn’t come? I’ll get you next time, twice. You know I’m good for it. “Doris, what if I throw in a $50 calling card?” mutates into “I’ll be charming at your office Christmas party if you do the dishes this month,” aimed at a befuddled partner who may or may not have yet realized that what they thought was a partnership is in fact closer to a mutual exploitation.

How tiresome, how demeaning to all parties involved—yourself most of all—to admit the logic of petty hucksterism into your actual life. But to leave money or advantage on the table is anathema, because you’re a hustler—not in the popular usage of being a tireless worker, but in the sense of always looking to hustle a mark, and the thing is, everyone is a mark. Five more minutes and then it’s bath time, you tell your 5-year-old nephew—and he goes for it without even negotiating! Cute kid, but weak, clearly not a winner. This mindset will get you far in life, but it comes at a cost.

The ultimate insight of the salesman is not that Everything Is Selling, although that can be true, to the degree that you embrace it. The actual jewel of wisdom that every salesman forges out of their agonies and humiliations, if they stay with it long enough, is that Everything Is Luck. Every hotshot hits stretches when you simply can’t close anyone. You thought that your success was a product of your gifts, but the success itself was a gift, a gift of randomness, of luck—and luck always turns. Starting one day, everyone hangs up, everyone says no. Why are you talking like that? a woman in Alabama says about your stupid sales voice, and just like that, your confidence is gone, without which you are utterly lost. Suddenly you understand that you are powerless, that you have less agency than an ant on the sidewalk, that you are no different from the losers you disdain, the two-sales-a-week scrubs exiled to the back-office cubicles, the ones who simply “don’t want it enough.”

What makes it even worse is that the guy across from you, the mumbling clown who until now couldn’t close a door, is all of a sudden closing everything, his name now at the top of the dry-erase board, the boss setting iced sodas on his desk unsolicited, patting him on the back—even as you, the former No. 1 telemarketer in America, who just had the executive parking space for, what, three weeks straight, suddenly has to stay late on Thursday night because you haven’t hit your weekly quota, a measly number that you used to crush by midday Monday. As you settle in for an after-hours shift among the new hires and loafers and no-hopers, many of whom are visibly satisfied to see you brought down to their level—and who can blame them?—you have to trust that the wheel will turn, even as you feel in your bones that it won’t, that you are cursed, that you are being punished for all those old ladies you ripped off, the 8 a.m. callbacks you scheduled.

You can take the subtle humiliations of being moved to the desk stacked with training materials, of using a headset with bare metal earcups because you forgot cash for foamies and the boss no longer tosses you a pair from the stash he keeps in his drawer. (Those foamies are for closers.) You can put up with the abuse and hang-ups and death threats from the customers who seem to have sensed your weakness before they even picked up, and the long weeks making no more than the subminimum base wage. But the worst part is not knowing how long your cold streak will go on, if it will last days or weeks or months—or, as in my case, forever.

Before my luck could turn back, the company’s ran out. One day, more or less out of nowhere, it declared bankruptcy. The call center stayed open, but every call was to a pay phone, a dentist’s office, a tollbooth on the New Jersey Turnpike, instead of living, breathing, hot-blooded marks. The company was recycling the dregs, buying tranches of the cheapest trash leads on the market because it couldn’t afford the good ones. It soon decided to clean up the telemarketing division now that it didn’t matter anymore. I was one of the first to go, technically for not making my required disclosures—about cancellation fees, international rates, all that fine print nobody ever bothered to recite—on a sale. This was true, as far as grounds for termination go, though I had never made any required disclosures on any of the hundreds of my previous sales.

We’re all trapped in the back-office cubicle pod, our desperation rebranded as hustle.

It didn’t matter; I’d saved up a lot of money, thousands in sales bonuses I hadn’t yet touched. I frankly felt relief as security escorted me out after my firing. As a guiding life principle, ressentiment is thin gruel, and after almost a year on the phones, I was happy to be leaving behind a world of ethical squalor, the never-ending petty wheedling hustle. I’ll never live like that again, I thought. How naive I was.

In ways large and small, we live in a world shaped by telemarketing. When’s the last time you answered a call from an unknown number? How many tweets do you encounter without bots in the replies? Have you seen how many spam emails your parents receive? I chuckle to think how mad people used to get when we called during dinner—when do you have privacy now? Even your sleep app is hawking your data to companies trying to sell you melatonin gummies. Are these intrusions any less intrusive because they’re silent?

Worse yet, decades of wage stagnation and the emergence of the gig economy have generalized the anxiety and pressure that used to be the exclusive domain of sales sweatshops; now we’re all pitching all the time, unironically using phrases like “building my personal brand,” indefatigably selling versions of ourselves via social media posts that fool no one, soliciting eyeballs, donations, subscriptions, views and clicks, for our Twitch streams, OnlyFans, Substacks, stand-up shows, GoFundMes, podcasts, NFTs, sending emails to our agent like, “Another piece in Slate, hmm, wonder if there’s a book in this one?” Manufactured precarity and the Hobbesian competition of all against all, combined with the public insistence on moral rectitude, have us all scrambling for grievances so we can justify doing what we must—even presidents and billionaires insist they are victims now. We’re all trapped in the back-office cubicle pod, our desperation rebranded as hustle, bitter entrepreneurs of abjection competing for the same dwindling pool of broke rubes.

Which brings me to the third elite salesperson. At the coffee shop I frequent, there are a number of panhandlers who come in regularly to beg for money. Most of them ask for change or a dollar in a desultory tone, open palm out, and get little or nothing. But one man comes in, walks up to a table, falls to his knees, interlaces his hands as if in prayer, and begs, at the top of his lungs, Please please please, money, please I need a dollar! This display of raw emotion is jarring even to jaded New Yorkers; he once did it to a European tourist next to me who scrambled to her feet, stammering, Oh God, what, what did I do, what do you want?, near tears. He only begged louder, scooting after her on his knees.

Without fail, wallets are produced, cash is handed over. Anything to make it stop. Once he gathers $15 or $20, he dusts off his pants and walks out, smirking faintly, to his waiting girlfriend. The baristas and the other regulars dread his appearances, but I recognize him as the exemplar he is: The spirit of our era resides in this man.

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/shawmedia/NHFPZUE7OAAAFD7NBI4RWUDRZU.jpg)