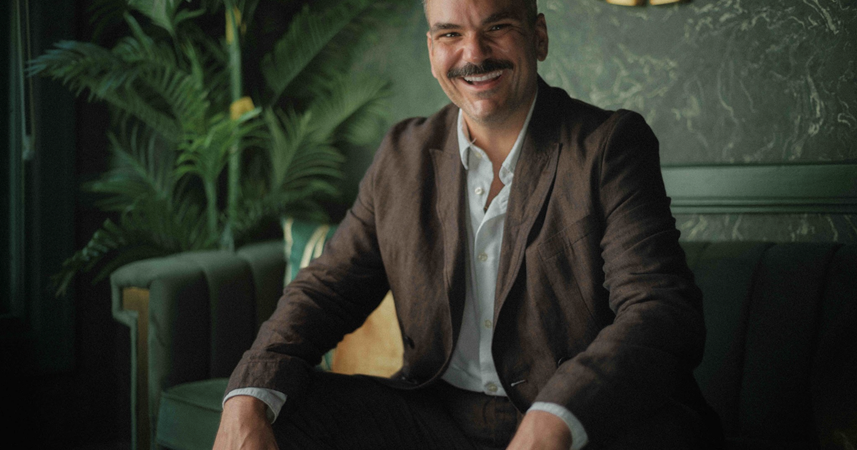

When comedian Ian Karmel headlines at Comedy on State this week, his hourlong set will include jokes about the indignities of getting older and trying to stay healthy.

The 39-year-old comedian and former head writer for “The Late, Late Show With James Corden” never told those kinds of jokes before. Karmel always assumed that getting old wouldn’t be an option for him.

For most of his life, Karmel had a weight issue, at one point hitting 420 pounds. He also developed a hard-partying habit in college that provided good material for his stand-up act, but made him assume that he’d never make it to 50.

“Not to be morbid, but when you weigh 420 pounds, you don’t really think about the future,” he said. “Because it’s scary to think about the future. So all of a sudden, I found myself facing down 40 and thinking a lot about aging.”

Having dropped 180 pounds during COVID, Karmel has chronicled his adventures with food and drink in his new memoir, “T-Shirt Swim Club.” Coming out on June 11, the book mixes funny and true stories by Karmel with commentary by his sister, behavioral psychologist Dr. Alisa Karmel.

In a Zoom interview from the streets of New York City, Karmel talked about the book, coming back to stand up comedy after eight years in James Corden’s writers’ room, and why he’s grateful and surprised to be getting old.

Ian Karmel wrote his memoir “T-Shirt Swim Club” with his younger sister, clinical psychologist Alisa Karmel.

What’s it like to be back touring regularly after eight years?

It’s been such a trip because so many things have changed for me. The biggest change for me was that I lost 180 pounds between the eras when I was going out headlining. That was the biggest adjustment, trying to figure out who I was onstage.

I had my comedic persona pretty much locked in since I was four years old. I had to figure out why I’m funny again and what the audience will think the second I walk out on stage. Which is why I grew the mustache.

So in comedy, a mustache equals 180 pounds? That’s the exchange rate?

There are very few rules in stand up comedy, but that’s one of them. It’s like a third eyebrow now.

What did you learn from writing for “The Late, Late Show” that you took with you when you returned full-time to stand-up comedy?

Just how to write jokes. You’d have to crank out 100 jokes a day, just for the monologue alone. So I learned to be really disciplined about writing.

And then for the last three years of the show, I was kind of like our Andy Richter. I was his sidekick. It was like stand-up comedy methadone, where it wasn’t the pure stuff I was used to, but it was enough to remind me about timing and all these other things.

What are you talking about on stage these days?

It’s a lot of jokes about getting older. Finding out that you’re old kind of hits all at once. I have this joke I do at the top which is 100% true. I heard a Vampire Weekend song in a commercial for blood pressure medication. I used to do drugs to that Vampire Weekend song, and now I’m on that medication.

It was like, ‘Oh, this is the moment. This is the sign.’ It’s about aging — what’s fun about it, what’s startling about it, and how to cope with it.

Based on the last 40 years, you sound grateful and surprised to be here and facing these things.

Incredibly grateful and surprised. And also jokes about how we treat fat people, which is where the book came from. I had this crazy experience where I went up on stage, and I was trying to tell jokes about being fat. And I’ve put on a little bit of weight since then — this was at my lowest. A woman came up to me after the show and said, “Hey, I don’t think you should talk about that stuff anymore.”

I think she thought I was making fun of fat people, when I was just trying to talk about my own experience. This was the previous 35 years of my life. It’s coded into my bones and my brains and my soul.

That had been a part of your own self-image, both internally as well as externally.

Exactly. I mean the reason you become funny in the first place is out of a sense of vulnerability, and you want to head people off at the pass, because they’re going to make fun of you. Let me make the jump first, because at least then I’m in on it and have some sense of agency.

To me, that was a very jarring but helpful experience. I was a little annoyed at the woman at first, but I’ve been grateful every day.

Who did you write the book for? Did you have your younger self in mind?

My younger self, but I also wrote it for the kid who is 14 or 15 years old right now who’s fat and struggling with how to deal with it and feeling like nobody really understands what he or she is going through. I tried to get as specific as I could in the book because I think that’s how you relate to people.

When you’re fat, we hear so many platitudes. We hear them from the people who love us the most. And it’s wonderful but it doesn’t mean anything. Because when somebody says, “Oh, you’re beautiful, don’t worry about it,” you’re like, “Oh, thank you, but that doesn’t match up with any of the experiences I’ve had in the world for my entire life.” It’s nice but it’s not helpful. So I wanted to write honestly and candidly, but in a funny way.

How did it work to write the book with your sister?

I write about all these things in 13 essays, that kind of function as sort of a memoir. And then my little sister writes an addendum to every single chapter. She is a Doctor of Clinical Psychology and she comes in with, “This is what was going on with him while this was happening. This is what’s going on with fat kids in general.”

She does a very good job of making these heavy concepts a little more digestible and accessible. It would have been a joy to write this book alone, and I think it would have been helpful to people. But the fact that she’s a part of this book is going to make it really special and something that can reach out to people and help them.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24435784/tokyostrava.jpg)