Sports

How Bill Walton became a voice for those who stutter

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAs a child, Maya Chupkov had what she describes as a “really debilitating stutter”. In kindergarten, she struggled to speak at all and was teased for it relentlessly.

“I tried so hard to hide it, and it took a lot of energy out of me,” she told the BBC this week from her home in San Francisco.

To cope, she turned to sports like basketball and volleyball.

“Sports was just my happy place, where I could just be on the court, excel and have fun with my friends without needing to talk,” said the now 31-year-old.

Growing up, one of her idols was Bill Walton – a college basketball superstar and National Basketball Association (NBA) hall of famer who later built a successful career as a sports broadcaster, despite having a stutter for all of his life.

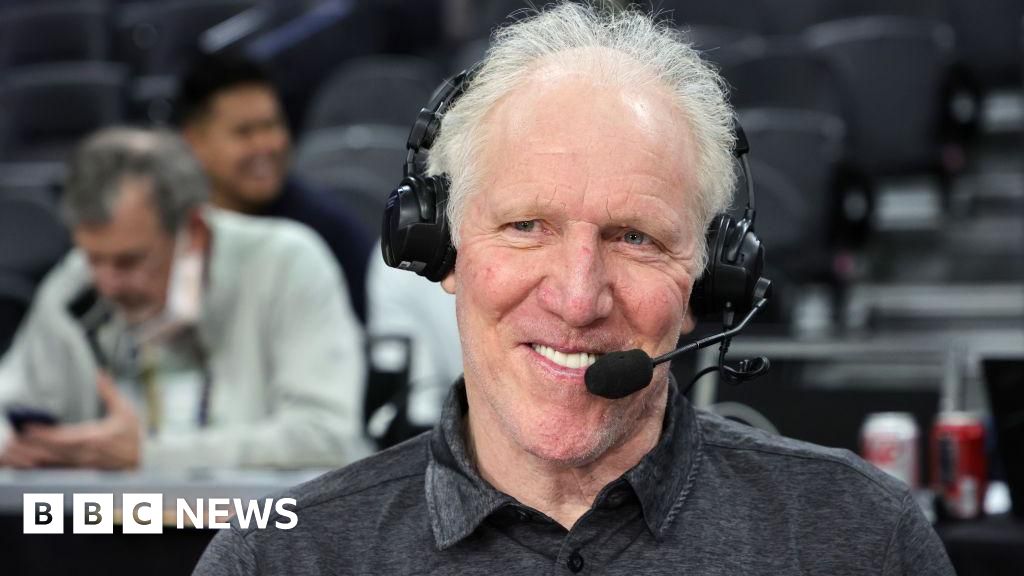

Walton died on Monday at the age of 71 after a long struggle with cancer.

Some fans, including Ms Chupkov, are now paying tribute to him for his years of advocacy for others with speech impairments.

“The fact that he was so successful with a stutter just always kept me going,” said Ms Chupkov, who hosts the podcast Proud Stutter.

Walton is perhaps best-known for his legendary college basketball career.

In his three years of playing for the University of California, Los Angeles, he led the Bruins to two championship wins and an unmatched 86-4 win record.

In the state of Oregon, he is celebrated as being instrumental in securing the Portland Trailblazers’ first – and only – NBA championship in 1977.

But for many people with stutters, Walton was a role model who spoke openly about navigating his own speech impediment as he built his Emmy Award-winning broadcast career, marked by his colourful commentary and charisma.

“People like Bill Walton are so important, because he’s like: ‘Look, I stutter sometimes, and here I am an announcer on NBC,’” Jane Fraser, president of the US-based Stuttering Foundation, told the BBC.

Maya Chupkov

Maya ChupkovStuttering – or stammering – is a type of speech disorder where the flow of spoken words is disrupted by repetitions, prolonged sounds or silent pauses.

It is estimated that more than 80 million people – or about 1% of the world’s population – stutter, according to the Stuttering Foundation.

Of them, three million are American, including President Joe Biden, who has spoken about the challenges he faced with a stutter stemming from childhood.

“I used to find it hard talking on the telephone, or stand up in front of people and talk,” Mr Biden said earlier this year as he gave advice to a nine-year-old boy who also stutters.

Scientists don’t yet know what causes stuttering, but research suggests it could be tied to the region of the brain responsible for planning and executing speech.

There is also no known cure for stuttering. Instead, treatment focuses on speech therapy and finding strategies that can help a person cope and live with it.

Throughout his public life, Walton was candid about how he navigated his stutter.

In an interview in the 1990s with the Stuttering Foundation – where he served as an ambassador – he recalled basketball being a sanctuary.

The sport also offered him a method to manage his stutter, he said, as he applied techniques he used when playing basketball to working on his speech – like focusing on the basics.

When a chronic foot injury brought an end to his professional playing career at age 36, Walton pivoted to broadcasting.

It was not an easy transition, he told the foundation, because it brought up old insecurities about his stutter.

Ms Fraser, president of the Stuttering Foundation, said that Walton was one of the most engaged celebrity ambassadors her organisation has ever had.

“If someone contacted us and said they would like to reach out to Bill (for advice), we knew that he would always answer,” she said.

His advocacy has inspired other professional basketball players, like former NBA player Michael Kidd-Gilchrist, to be forthright about their own speech impediments.

“It was great for me to witness him,” he said, calling Walton a “pillar” for both basketball players and people with stutters.

After playing in the NBA for eight years, Mr Kidd-Gilchrist started a charity focused on getting speech therapy covered through health insurance to help American low-income families afford the often expensive therapy.

He said that, while basketball provided him with a community growing up, it also brought a new set of challenges once his professional career took off. Suddenly there was pressure to give media interviews.

“It took its toll on me mentally at a young age,” the 30-year-old said.

He said his foundation serves as an outlet to both be open about these struggles and to challenge stigma around stuttering.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesMany misconceptions exist about people who stutter, he said.

These include the false assumption that people who stutter are not smart, or that it is a sign of nervousness or stress.

But in reality, “it’s not a bad thing”, he said, “and I think Bill Walton is a testament to embracing stuttering”.

Another misconception is that stuttering can always be “overcome”, said Ana De Jesus, a 24-year-old college basketball player for California State University in Northridge.

She said while she faces that expectation, “the path that I am on is more of acceptance”.

It was that message Walton tried to impart through his advocacy.

“I used to be really embarrassed about stuttering,” he once said.

“But now I realise that it’s something that is part of me, something that I have to deal with and work on everyday.”

With his many accolades, Ms Fraser said Walton “built a long tradition of helping others” that will reverberate for future generations.

“I think that’s his immortality,” she said.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/112124-nordstrom-makeup-deals-social-a0f2aee5c0a545408c24f2a45955690c.jpg)