World

In Wildness Is the Preservation of the World

Loyal readers of this magazine know that we are preoccupied with matters of climate change, and that we worry about the future of our home planet. I appreciate (I really do) Elon Musk’s notion that humans, as a species, ought to pursue an extraplanetary solution to our environmental crisis, but I believe in exploration for exploration’s sake, not as a pathway to a time share on Mars.

So we at The Atlantic are focused intensely on, among other things, the relationship between humans and the natural world they currently inhabit. We have a long history of interest here. The great conservationist John Muir more or less invented the national-parks system in The Atlantic. John Burroughs defended Charles Darwin in our pages. Rachel Carson wrote her earliest essays, about the sea, for us. And, of course, The Atlantic published much of Thoreau’s finest and most enduring writing.

In our lead essay this month, our senior editor Vann R. Newkirk II argues that America owes a debt to other nations for its role in accelerating climate change, and that paying this debt may be the best way for the world to save itself. “For at least the immediate future, wealthy Americans will be protected from the worst of the climate crisis,” he writes. “This comfort is seductive, but ultimately illusory.”

Climate change is one reason I asked our staff writer George Packer, the author of the National Book Award–winning The Unwinding, to identify a place that could somehow stand in for America’s fundamental quandaries, hypocrisies, and powers of self-correction and improvement. Against his better judgment (he doesn’t like the heat very much), Packer found himself returning again and again to Phoenix, where, he became convinced, the future is being determined—not merely our political future, but our relationship with the natural world, on which our survival depends. Packer’s cover story possesses the grand sweep, capacious reporting, and powerful insight our readers expect from him.

Although he appreciates Phoenix and understands it in a complicated and not-unhopeful way, I think Packer would have preferred the assignment we handed our science writer Ross Andersen, who visited Greenland to investigate the technological means through which it may be possible to save otherwise-doomed glaciers. His article, “The Glacier Rescue Project,” is fascinating, and especially important in a moment when too many people believe that catastrophic sea-level rise is inevitable.

The Atlantic has large ambitions and a peripatetic staff, so when we heard that Australia’s koalas were suffering from both climate change and chlamydia, we quickly dispatched Katherine J. Wu, a staff writer (and a microbiologist), to Adelaide and beyond to bring back a report. I believe this marks the first time that marsupial chlamydia has been covered in The Atlantic. Wu’s story is a revelation, illustrating the difficulty that even wealthy nations have in protecting their most prized species during a period of climate instability.

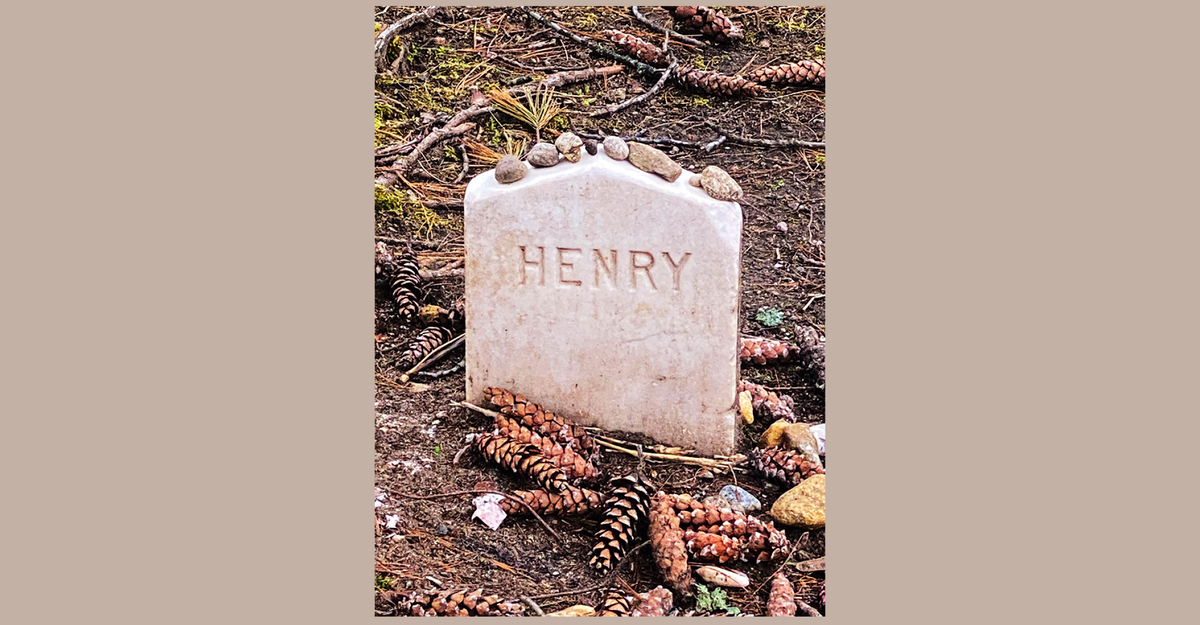

Me, I went to Walden Pond. I visit occasionally, walking the path that starts behind Ralph Waldo Emerson’s house and ends up near the pond’s big parking lot and little beach. Thoreau would be surprised by Walden Pond today: more visitors, much more noise. The noise could get worse soon. A proposed plan to radically expand a nearby airport for private jets has conservationists and preservationists worried that an appreciation of the sanctity and history of Concord is not unanimously shared. One doesn’t have to live like Thoreau to understand that wealth comes in many forms—in the wildness of the world, for instance—and that returning the planet to some sort of equilibrium is a universal interest.

This editor’s note appears in the July/August 2024 print edition with the headline “In Wildness Is the Preservation of the World.” When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.