World

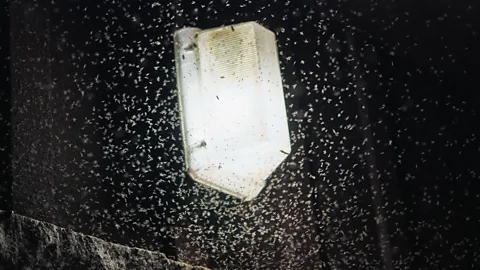

‘A warmer, sicker world’: Mosquitoes carrying deadly diseases are on an unstoppable march across the US

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWest Nile virus, Eastern equine encephalitis (EEE), malaria and dengue are gaining new ground in the US. The mosquitoes that carry these diseases are thriving in a warming world.

Since the turn of the century, New York City has experienced 490 cases of West Nile viral fever according to the city’s health department, a disease spread by infected mosquitoes. One of the most high-profile recent cases was Anthony Fauci, chief medical advisor to the US president from 2021-22.

Why is there no vaccine for West Nile virus?

The sporadic nature of West Nile outbreaks has been one of the major challenges to designing trials of candidate vaccines, says Carolyn Gould, a medical officer with CDC’s Division of Vector-Borne Diseases.

But the need for a vaccine is urgent, says Paul Tambyah, president of the International Society for Infectious Diseases, who has said its absence so far is down to “a lack of imagination”.

According to infectious disease experts, unusual patterns with mosquito-borne pathogens are becoming the norm. Earlier in September 2024, a man in New Hampshire was reported by his family to have been hospitalised with not one but three mosquito-borne illnesses at the same time: West Nile fever, EEE and St Louis encephalitis.

“What we’re seeing more and more is people infected with multiple mosquito-borne diseases at the same time,” says Chloé Lahondère, a biologist who studies blood-sucking insects at Virginia Tech.

Within the US, and around the globe, mosquito-borne diseases are popping up in increasingly atypical places. “Last year, we had locally acquired cases of malaria in the US for the first time in 20 years,” says Desiree LaBeaud, a professor of paediatrics and infectious disease at Stanford University.

The climate connection

Much of this is related to shifting climate patterns, which are allowing various mosquito populations that carry these viruses, such as various sub-species of the Aedes genus of mosquitoes and the species Culex coronator, to spread into new areas. As temperatures rise, mosquitoes can invade and thrive in habitats which once represented hostile environments. Since it was first detected in Louisiana in 2004, C. coronator has spread to almost of the south-eastern states, bringing diseases such as West Nile and St Louis encephalitis, while other mosquito species are finding that they can comfortably survive even further north.

“People have been surprised by Aedes-borne diseases like dengue popping up in California,” says Sadie Ryan, a professor in medical geography at the University of Florida. “But once they examined all the mosquito surveillance data, they were finding these species in traps even quite [far] north in the state, which hadn’t been seen before. They’re not very well established there yet, but it’s a warning.”

With even mountainous regions becoming warmer and more mosquito-friendly, diseases like malaria and dengue are even beginning to reach some of the most remote places on the planet. For example, while malaria is endemic to Nepal, the disease incidence is increasing in the hills and mountains of the country, locations previously considered malaria-free. “Malaria is very much thought of as a lowland disease,” says Paul Tambyah, president of the International Society for Infectious Diseases. “But now the definition of lowland is creeping upwards as the temperatures get warmer, so mosquitoes are able to survive at altitudes.”

This is predicted to have drastic consequences for public health. Mosquito-borne diseases already afflict around 700 million people every year, resulting in one million deaths. Over the next century, climate projections suggest that around one billion people, mainly in Europe and subtropical regions, will be infected by a mosquito-borne virus for the first time, while disease transmission within parts of Asia and sub-Saharan Africa is expected to transition from being seasonal to year-round.

Some researchers have described this as a steady move to “a warmer, sicker world”. But to understand why this is happening, we need to understand a little more about the biology of mosquitoes and their life cycles.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesUnlike humans and other mammals, mosquitoes are cold-blooded creatures and so are incapable of self-regulating their body temperature. This means that every aspect of a mosquito’s short life, from its bite rate to how quickly it matures and ages, is dependent on the temperature of its environment.

Different mosquitoes have different temperature preferences. Aedes triseriatus for example, is perfectly happy in temperatures as low as 22C (72F), making it particularly hardy for a mosquito, and enabling it to live in regions ranging from Florida to southern Canada. Aedes aegypti, on the other hand, does best in temperatures of around 29C (84F). As temperatures in Europe and the US have risen, the mosquito’s range and transmission ability has expanded.

Ryan and colleagues have found that warmer temperatures have led to extended mosquito breeding periods, and a corresponding increase in disease outbreaks transmitted by the insects.

“If temperature rises and stays within the range the mosquitoes can tolerate, it can allow some species to develop faster, expand their range and lead to larger mosquito populations which can then have an impact on public health,” says Lahondère.

But while most research has focused on the impact of climate change on Aedes aegypti, it is another Aedes species, Aedes albopictus, which has perhaps been the main beneficiary so far from our warming world. These mosquitoes thrive at around 26C (79F), so milder winters and warmer periods during the early spring and autumn across North America and Europe are creating conditions far more to its liking for much of the year. This has enabled it to establish a vast range across Europe and in 36 states across the US.

Beyond warming

Because Aedes albopictus does well in relatively mild conditions, just as we do, the mosquito can easily move from place to place via human transport, which researchers have found to have facilitated its spread through Europe. “Because it has a slightly cooler climate tolerance than Aedes aegypti, it can tolerate winters and has established itself throughout the eastern seaboard of the United States,” says Erin Mordecai, an infectious disease ecologist at Stanford University. “It’s become a major invasive threat because it can transmit dengue, chikungunya, Zika and other viruses.”

“Dengue outbreaks in the US are a concern given the reports of local transmission recently and the potential for this disease to cause large epidemics, as it has done in Latin America for the past couple of years,” says Mallory Harris, an infectious disease researcher at the University of Maryland. “Vaccines against dengue are just starting to be rolled out, but there have been some issues. For example, Sanofi has stopped producing its dengue vaccine [for children] because of low demand. So we’re not very well prepared right now to respond to a large dengue outbreak in the US.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesEnvironmental pollution is also encouraging the spread of mosquitoes. Researchers have shown that certain mosquito species, dubbed “container breeders” such as Aedes aegypti and the malaria mosquito Anopheles stephensi, enjoy breeding in the ample plastic waste discarded by humans, especially if it contains some stagnant water from rainfall.

“An Aedes mosquito can lay 200 eggs in a coke bottle cap,” says Ryan. “That’s why you should worry about little bits of trash with a bit of water building up in them.”

But it’s not only empty plastic caps and bottles which attract mosquitoes. Lahondère says that they can find a home in pretty any man-made container from old tires to plant-pot saucers, with habitats ranging from people’s backyards to landfills. “The key thing is that water needs to be stagnant for a while for the mosquitoes to develop,” she says.

Intriguingly, Lahondère has found that Aedes albopictus and Aedes aegypti have learnt to feed on various ornamental plants and wildflowers in back gardens as a way of adapting and flourishing within urban habitats. “The fact that they’re attracted to plants that they didn’t evolve with in their native range is interesting because it demonstrates their opportunistic feeding behaviour,” she says. “By providing these sugar sources in our backyards, we’re contributing in some ways to their wellbeing.”

But before you throw out your potted plants and dig up your backyard, mosquito researchers feel that ultimately the onus is on politicians to do more to address climate change, and public health organisations to invest in vaccines and novel forms of mosquito control.

With scientists exploring strategies ranging from killing mosquitoes with toxic sugar baits or sterilising them through genetic engineering, there are various options for reducing the burden on human populations.

“All these ideas have various effects and impacts on mosquito populations and need to be species-specific, but they provide hope for the future,” says Lahondère. “But most likely not an entirely mosquito-free future though.“