Tech

AI gives Hong Kong boy grieving for late brother chance to reconnect

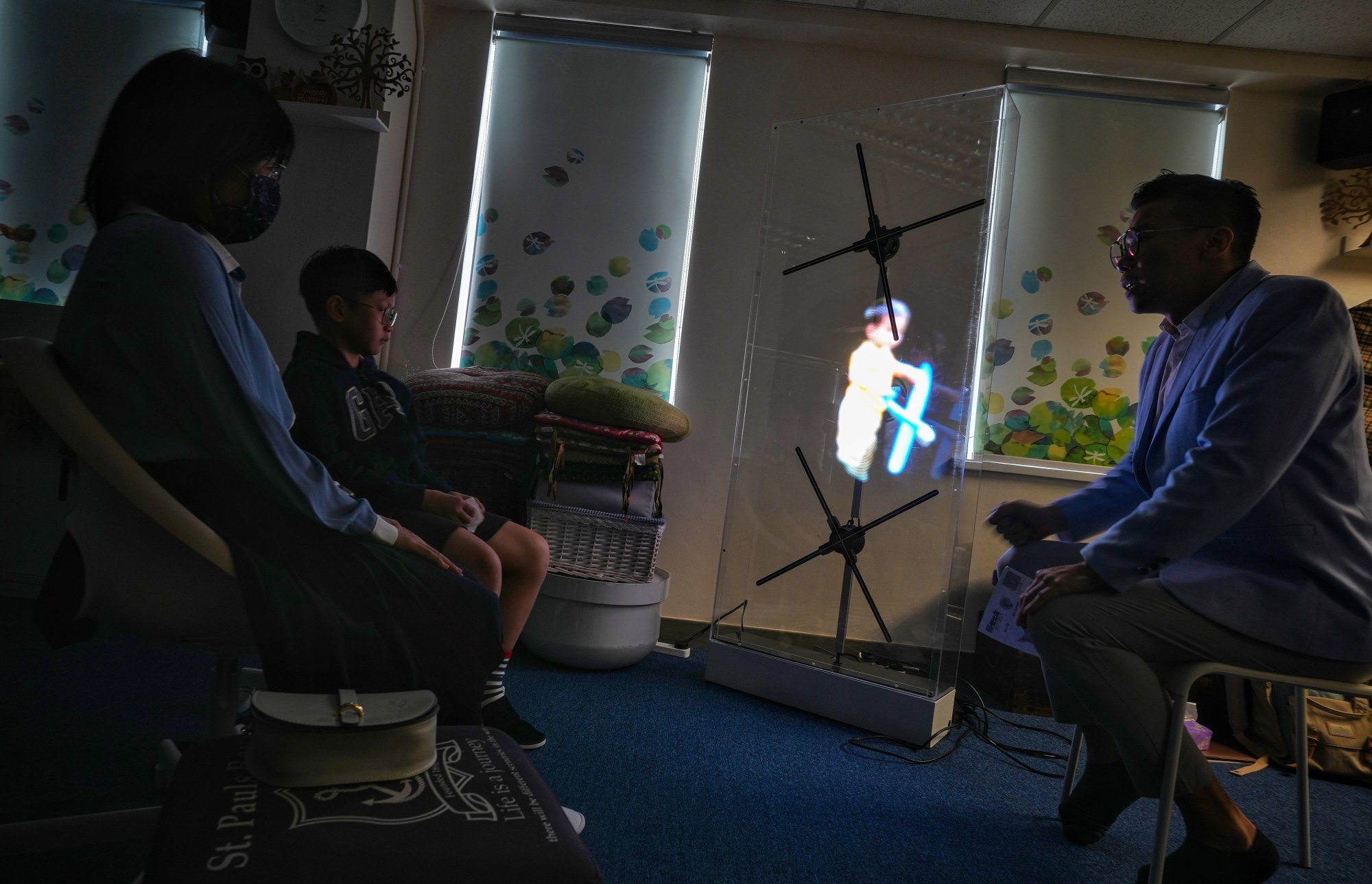

Morris, whose parents enrolled him in grief management at a hospital, was one of the beneficiaries of the Dreams*2Gather programme run by the non-profit Love Our Kids Foundation, which helps young patients fulfil wishes that could be hindered by their physical or mental conditions.

With the help of volunteers, multiple start-ups and technology firms contribute their expertise to create AI versions of deceased loved ones, with family members of the beneficiaries also able to take part in the process.

His mother said the recreation was a chance to bring out the love Morris felt for his late brother.

“I was actually touched when Morris cried [upon seeing the recreation],” she said. “I didn’t know that after such a long time, his affection was still there.”

The 41-year-old former piano teacher added that she chose to have Yat-lai portrayed as a toddler learning how to walk, as that would have been the next stage in life had he survived.

The mother of three lost Yat-lai to the autoimmune disease that was only diagnosed after months of fruitless medical tests and persistent pneumonia during the pandemic.

He died, aged just seven months, just as he was about to receive treatment in February 2020.

Because of social-distancing rules imposed over the pandemic, the mother and father were the only two people allowed to visit Yat-lai in his hospital ward.

They had decided against telling the rest of the family he was living his last moments to spare them the sight of how ill he was.

But that decision has become a lingering regret for the family, especially for Morris.

Besides their work creating the portrayal of Yat-lai, the volunteers reconstructed the image and voice of a deceased mother using artificial intelligence. Her adult and teenage daughters were able to see and hear their mother’s voice responding to a letter they had written, with the script penned by volunteers.

The mother praised her young daughters for persevering in life and for their emotional support for the rest of the family after her death.

Professor Lee Tan, an associate dean of education at the Chinese University of Hong Kong’s engineering faculty, reconstructed the woman’s voice.

Entrepreneur Tom Tong Kwun-wah created her facial expressions and Lawrence Cheung Cheong-ming, the head of customer and product support for the virtual reality division at HTC, constructed the virtual reality living room where she was placed.

Tong said it was a challenge to produce accurate mouth movements to match Cantonese pronunciations, as most software was designed to fit English speakers.

Lee had to work with less than a minute of recorded broken phrases to produce a fluent one-minute speech, but he said the technical challenges were irrelevant in the face of the emotions involved.

“Let’s say if we have improved the recording by tenfold in engineering terms, would that mean the family would find it better?” Lee said. “We cannot equate technological proficiency with the family’s feelings.”

The professor said his team’s product could capture the mother’s accent and voice but it could do better in mimicking her cadence.

Lee, whose start-up Vocofy AI has developed a text-to-voice model that preserves the original voices of people who have lost the ability to speak, said his team would usually turn down private requests to recreate voices of dead people because of ethical concerns.

But he took up the family’s project as he was touched by the daughters’ story and knew that they had consented to a limited reproduction of their mother’s voice.

“I am relieved. This is a motivation for me to continue my work,” Lee said. “Technical competency isn’t the key matter to me, but rather that the technology is used well.”