Fashion

BOOM: Judge Blocks $8.5B Fashion House Merger

Welcome to BIG, a newsletter on the politics of monopoly power. If you’d like to sign up to receive issues over email, you can do so here.

“Antitrust has come into fashion.” So wrote Judge Jennifer Rochon in handing down a temporary injunction blocking the $8.5 billion merger between fashion houses Capri and Tapestry, a deal that would put “affordable luxury” brands Coach, Kate Spade, and Stuart Weitzman, Michael Kors, Jimmy Choo, and Versace all under one roof and dramatically consolidate the industry.

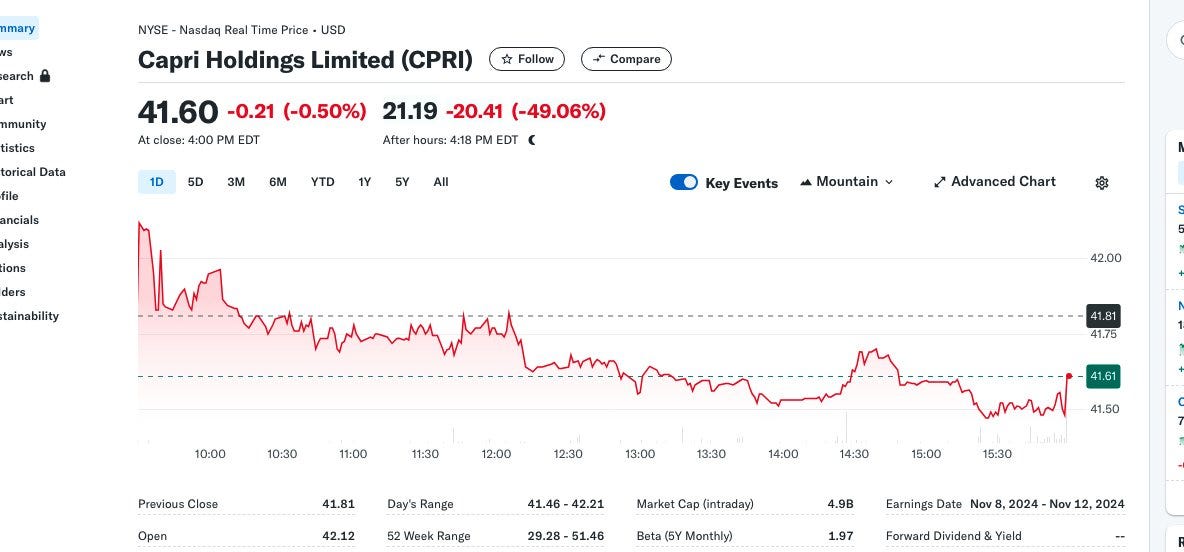

This deal was big on Wall Street, with merger investor specialists imagining that the Federal Trade Commission’s case was a disaster. “It’s not even throwing wet spaghetti at a wall to see what sticks. It’s not even wet,” said speculator Paul Cerro. “They’re just throwing dry spaghetti at a wall and hoping it’s going to stick.” Basically, finance bros bought into the narrative that the courts will punish Lina Khan for being aggressive. But in reality, the FTC is just enforcing the law on the books, and winning.

Oops.

This case does have some legal implications. This is the first case I’ve seen where the judge acknowledges and accepts the 2023 Merger Guidelines put out by the agencies, on two fronts. Judge Rochon found the new concentration thresholds made sense. She also bought into the new approach of seeing a loss of head-to-head competition as a condition for finding a merger unlawful. The judge also built on precedent from Google, IQVIA, Illumina and Microsoft-Activision to move merger law more towards seeing market realities instead of theoretical modeling. Case law, in other words, is becoming more Lina Khan-ified.

As I read the decision, it seemed that Rochon’s thought process was as follows. She looked at the documents and testimony from the executives in which they talked internally about how they were key competitors and if they merged they could raise prices, to the tune of hundreds of millions of dollars in extra costs per year for consumers. One slide presented to the board of Tapestry on the acquisition, for instance, said, “Coach has been priced an average $147 above [Michael Kors] for the last 2 years; suggesting room to increase MK AUR.”

Presented with these documents, Judge Rochon saw the obvious. “The evidence reflects,” she wrote, “that Tapestry perceived the acquisition of Michael Kors to be an opportunity to decrease Michael Kors’s discounting and increase Michael Kors’s prices.” Executives testified they would never do what they said they would do in private, but the judge wasn’t persuaded. “The Court does not credit these self-interested statements,” she wrote.

In sum, compelling and significant ordinary-course evidence indicates that Defendants are particularly close competitors. Despite the efforts of Tapestry and Capri witnesses to “minimize the significance of the evidence of head-to-head competition between” them, “the documents tell the story.”

After establishing what would likely happen, Rochon worked backwards to the economic models presented in the case that could add theoretical weight. Most of the decision goes into long and detailed analysis of the different technocratic models of the economic experts.

The government expert, Loren K. Smith, did a market share analysis, a pricing analysis, and defined the market in different ways to show that, though there are many different handbag producers, the “affordable luxury’“ market is distinct. He found the merger would lead to market shares of between 59% and 83% of the market, which is far higher than the threshold of 30% traditionally considered in merger cases based on relevant Supreme Court precedent.

The expert for the merging parties, Fiona Scott Morton, is a Yale professor and former Obama antitrust enforcer, and she argued against Smith at every point. She was not persuasive, at all, largely because her analysis contradicted what those executives said. Morton even tried to say, bizarrely, that these companies would still compete even if they were all part of the same conglomerate, instead of cooperating to raise prices. That’s a weird statement, to assert a corporation wouldn’t profit maximize.

The judge repeatedly cast doubt on Morton’s analysis, citing Morton’s own earlier academic work and calling her arguments “inconsistent.” When Rochon asked her how claim that the brands would still compete even if they all were owned by the same company, she responded by saying “it’s hard to explain from the outside.” Judges tend to throw shade in footnotes. Rochon was polite, but that’s what she did.

Morton matters beyond this case. She runs a progressive antitrust center at Yale called the Thurman Arnold Project, and is trying, absurdly, to take a big public position in the Google remedy discussion as a tough enforcement-minded person. Despite her American citizenship, she was nearly hired in the European Union as the chief economist for the Directorate-General for Competition, their main antitrust agency. Morton’s career is a good illustration of why antitrust has been a disaster for so long, and why much of business and antitrust in academia is not credible. Her position as a paid expert witness to foster consolidation is one thing, her willingness to engage in deceptive arguments for money while posing as an disinterested progressive academic is disgraceful and corrupt.

The big picture here is pretty simple. As antitrust enforcers bring more cases, judges are actually grappling with the realities of commerce and the law. For years, we’ve been told that the judiciary would *never* accept more assertive antitrust. But it turns out, some judges do, and some judges don’t, and now there’s a bunch of useful case law they can cite. More of them, including Rochon, do not buy the premise that one should never interfere with the magic market. Instead, they are applying precedent, and accepting the merger guidelines anchored in it.

In other words, no one in the courts is punishing Lina Khan for bringing cases. And that’s why Wall Street is extremely angry.

On another level, is this merger case in fashion that important? CNBC did a segment mocking the very notion, calling the case a waste of taxpayer money. But it is an $8.5 billion deal, and would injure a lot of consumers, and some workers. Before the Biden administration, blocking a multi-billion dollar deal in court would be a legacy-defining case for an FTC Chair or Antitrust Division chief. Under FTC Chair Lina Khan and Antitrust Division chief Jonathan Kanter, it’s just, well, Thursday.

Thanks for reading. Send me tips on weird monopolies, stories I’ve missed, or comments by clicking on the title of this newsletter. And if you liked this issue of BIG, you can sign up here for more issues of BIG, a newsletter on how to restore fair commerce, innovation and democracy. If you really liked it, read my book, Goliath: The 100-Year War Between Monopoly Power and Democracy.

cheers,

Matt Stoller