Celebrated Boulder adventurer Cory Richards was standing on top of the world in 2016. And his world was bottoming out.

In the climbing community, Richards says, summiting Mount Everest is really not all that cool. Climbing it without oxygen? That’s a different thing. “That kind of levels it up,” he said.

Of the nearly 6,700 who have successfully scaled Everest, only 221 have done it without carrying supplemental oxygen. Another 178 have died trying.

Boulder adventurer Cory Richards is author of the new book “The Color of Everything,” which describes his climbing accomplishments and mental-health struggles. Aug. 18, 2024.

This was something Richards had dreamed of doing since he was 14. Now, 20 years later, he was doing it.

Four hours into his final ascent, his partner turned around. Richards carried on.

“I ended up sitting on the summit of Mount Everest by myself alone after climbing through the night with no safety net,” he said.

In that moment, he felt what he calls not “the deep inner peace that comes with accomplishing something in the hardest way possible.” It was realizing that “you still can’t get away from yourself.”

At this moment of Herculean accomplishment, Richards said, “I felt literally nothing. And that was the wake-up call to my mental health.”

A week later, Richards was feted on “CBS This Morning.”

“And six months after that, I was in rehab.”

This is not the story that everyone tells.

Cory Richards’ self-portrait after summiting Pakistan’s Gasherbrum II later became the cover of a National Graphic anniversary edition.

A mental-health diagnosis at age 1

Cory Richards was born in Salt Lake City in 1981 to parents who introduced him and his older brother to skiing and climbing. But behind the facade of an idyllic and privileged childhood was a relentless message that something in Cory was broken.

“My mom first took me to see a psychologist when I was 1,” said Richards. “So that tells you how deep the story of mental health runs in my life.”

As a baby, Richards was fussy and temperamental. “I don’t know what’s wrong,” his mother told the doctor. “He just seems sad.”

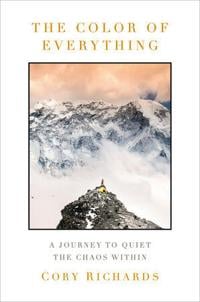

The cover of Cory Richards’ “The Color of Everything.”

Richards says his childhood was “challenging, to say the least.” He recalls normal stuff like bicycles and ice-cream trucks and swimming pools alongside toxic and sometimes violent family relationships. At age 12, he was diagnosed with depression. At 14 – the same year he dreamed of scaling Mount Everest – he was diagnosed as bipolar. He was in and out of psychiatric hospitals and 12-step programs throughout his teens.

It was the climbing community that pulled him out of it – at least for a time. At 19, on spring break from college in Montana, Richards summited 20,320-foot Mount Denali in Alaska. That was the start of a dizzying series of climbs that eventually landed him a job as a photojournalist for National Geographic (and made him a social media star on Snapchat).

Richards took his place in the record books in 2011 when he summited Pakistan’s Gasherbrum II, becoming the first American to successfully summit an 8,000-meter (26,247-foot) peak in wintertime. Only to be hit by a massive wall of snow and ice. “It sounded like thunder and a freight train and wind all at once,” said Richards, who only made it three steps before being swept up in the avalanche. In the cacophony, his mind heard his father screaming to him, “Swim like hell!” from half a world away.

Richards was being buried alive.

Once the avalanche overtook Richards and his two partners, “there was no more fear,” he said. Instead, the words of Boulder singer Gregory Alan Isakov filled his ears: “The past, she is haunted. The future, she is laced.” Richards had thoughts of unpaid parking tickets. A bowl of Cheerios. And the simple but undeniable understanding: “You’re dying.”

Only, he didn’t. When the storm of snow and ice stopped, he said, “my face was on the surface.”

Soon that face was on TV screens and magazines all over the world. His ice-bearded self-portrait ran on the cover of National Geographic’s 125th anniversary edition. He produced a documentary called “COLD” that chronicled the adventure.

But the tallest, hardest climb that Richards will ever make – toward some semblance of mental health – had not yet even made it to base camp.

Fast forward to 2021. By now, Richards had climbed Everest twice “and all this other (bleep) along the way,” he said. “Now I was going back to this same mountain to try to do something new and bigger and harder and more dangerous.”

His friends had this wild idea of trying to climb a new route on the highest mountain in the world. His pal Keith Ladzinski put together a team to make it all into a documentary. Much time, training and investment led up to a life-changing moment at the base camp, when Richards’ nose started bleeding. His sinuses clogged. He began crying and screaming uncontrollably. In that moment, he said, “my heart is beating and I am too alive. Too keenly aware of everything.”

He was having, as he describes it, “a full-on bipolar mixed episode.” That’s where a person experiences depression and mania at the same time. “Your brain speeds up to the point where you feel so confident and creative that you could (bleeping) conquer the world,” he said. “And at the same time, you are so depressed that you want to (bleeping) die. And both of those things are existing in your brain at one time.”

When Richards realized this was an actual neurodivergent moment, he surrendered. “There is nothing I can do anymore,” he said. “There’s nothing I can have. The beauty I surround myself with, the fame I’m in proximity to – none of that (bleeping) matters.

“I realized I was trying to dump water into a broken vessel, and it just keeps (bleeping) pouring out.”

At that moment, Richards realized, “I have to quit climbing.” And he did, right on the spot.

But that proactive act of self-care left dozens of friends feeling betrayed. Richards understood why. “Keith had put hundreds of hours – and hundreds of thousands of dollars” – into the project, he said. Another member of the documentary team wrote Richards’ parents, calling the entire episode “a vast, calculated manipulation.”

“I lost pretty much every friend on that expedition,” he said. All but one – Ladzinski, the one who lost all the money on the film that never happened.

Brandy Schultz, left, with husband Wesley Schultz, lead singer of The Lumineers, and friend Cory Richards, author of the new book “The Color of Everything.” Aug. 18, 2024.

Went to a garden party

On Aug. 18, an eclectic gamut of about 100 local musicians, artists, politicians, do-gooders and even a handful of journalists were invited to the Cheesman Park home of Wesley and Brandy Schultz. He’s the co-founder of the Grammy-nominated band The Lumineers; she’s the co-founder of Sound Future, a nonprofit that takes revenue from designated sporting and concert events and uses it for community-based nature restoration programs.

They gathered for an old-fashioned, high-fashion backyard garden party to launch the publication of Richards’ intimate memoir, “The Color of Everything: A Journey to Quiet the Chaos Within.” The Felice Brothers’ “Valley of Abandoned Songs” plays on the speakers while, on the kitchen counter between three potluck salads is a weathered 1940 hardback copy of John F. Baddeley’s travel adventure, “The Rugged Flanks of Caucasus.”

Wesley called the congress a variation on the “house-show mentality,” where bands invite friends over to play songs in someone’s living room. Schultz not only opened the door to his home, he cooked the pork shoulder and marinated the chicken shawarma because, he said, “I have always felt the human touch is important to everything.”

All in support of his friend – Brandy rather calls Richards his twin. “I’m just telling you objectively,” Schultz said, “this book is incredible.”

Brandy Schultz calls friend Cory Richards, left, and husband Wesley Schultz, lead singer of The Lumineers, “the twins.” Aug. 18, 2024.

All the adventure stories are there, but the point of the book is to encourage an open conversation about mental health, which is a subject Schultz can relate to. His dad was a psychologist who died in 2007, so he never got to see his son’s band become an international sensation. He never met his two grandchildren. He never saw this house with its designer pool and backyard grass as green as 1956.

“My dad was a tough dude,” Schultz said. “He’d be the guy in town you’d send him over to fight the dude from the other town.”

But then a funny thing happened on the way to the brawl, Schultz said: “My dad turned his life into a listener.”

Brandy and Wesley Schultz invited friends to gather in their backyard for a garden party and book launch for friend Cory Richards’ new book “The Color of Everything.” Aug. 18, 2024.

Like many, Schultz once attached a stigma to those seeking mental health services. “But my dad taught me what I would call emotional literacy,” he said. “Now I’m in a band where we all see a band therapist together when we can’t talk to each other on our own terms. It’s like having a referee. It’s useful. And I feel like Cory is doing something like that with this book. I think it shines a light on something that needs to be dried out in the sun.”

Richards spent much of the evening expounding on the book’s major themes of gendering, trauma and brokenness. That word, broken, shows up 42 times in it. The irony? “There is no broken,” he says emphatically. “Nothing was ever broken to begin with.”

Richards has come to understand that being labeled “broken” as a boy fostered in him what he calls “a value deficit.”

“My reaction to learning early on, specifically in rehab, when I’m 14 years old, that something is fundamentally wrong with me – was to buy into that accomplishment,” he said. “If something’s messed up with me and I’m fundamentally flawed from my core, then I am going to do everything in my power to prove my value. And look: It created beautiful things. And it also became deeply maladaptive and ultimately, yes, broke me.”

Richards’ greatest wish now for families who encounter neurodivergence in themselves or in their children, “is that we break the story of broken.

“Nothing’s wrong. Really,” he said. “There are complications and, yes, it’s complex. The brain is marvelous and malleable. It is at once durable and delicate and a universe unto itself. And sometimes it short-circuits. But nothing’s ‘wrong.’ As soon as we start telling the story that something is (bleeping) wrong, that’s the story that we inherit. And it’s hard to leave.”

The Lumineers are known for songs such as “Ho Hey,” “Flowers in Your Hair” and “Sleep on the Floor.

Richards understands the irony that the biochemistry that fuels his madness is the same biochemistry that has made all his brazen outdoor accomplishments possible. Life at -35 degrees will do a number on anyone’s head. “I also don’t wonder anymore about the irony of trying to stay sane to do insane things to escape insanity. The only places I feel normal are where nothing is normal at all.”

Now at 45, he’s redirecting all that courage and bravado and testosterone toward a new kind of Everest: Finding his purpose. That starts with forgiving himself. For all the people he hurt along the way. For all of it.

“I have this number tattooed on my hand,” he said. It’s a 10 to the 80th power. That’s a 10 with 80 zeros behind it.

“In the universe, there are 10 to the 80th atoms,” he said. “That means the probability that you exist as you is 1 in 10 to the 2,000,685th thousandth. It is a mathematical (bleeping) phenomenon that you are you. Think about it: One thing goes wrong throughout history. One. One ancestor since evolution – that’s 13.8 billion years – one thing happens in that time, and you are not here. Think about that for a second. That’s your (bleeping) purpose. To wake up and breathe and celebrate that experience every (bleeping) day of your life.

“It is outrageous that I have a body at all that gets to be bipolar. Are you (bleeping) kidding me? I won the lottery. That’s my purpose, just to breathe and love and be loved. That’s it.”

Brandy Schultz, CEO of Sound Future, welcoming visitors to her backyard on Aug. 18, 2024.

Brandy and Wesley Schultz, left,invited friends to gather in their backyard for a garden party and book launch for friend Cory Richards’ new book “The Color of Everything.” Aug. 18, 2024.

Wesley Schultz is originally from New Jersey and tried to make it as a musician in New York City. But in 2009 he left the city for Denver, where he and the band rose to fame and where he still calls home.