Entertainment

China censored hip hop, but now it’s back – without the drugs and the sex

The announcement from censors came at the peak of that frenzy. A silence descended, and for months no rappers appeared on the dozens of variety shows and singing competitions on Chinese television.

But by the end of that year, everything was back in full swing. What had looked like the end for Chinese hip hop was just the beginning.

“Hip hop was too popular,” says Nathanel Amar, a researcher of Chinese pop culture at the French Centre for Research on Contemporary China. “They couldn’t censor the whole genre.”

Chinese rapper Feezy on ‘woke’ hip hop and his new album The Weatherman

Chinese rapper Feezy on ‘woke’ hip hop and his new album The Weatherman

Since then, hip hop’s explosive growth in China has only continued. It has done so by carving out a space for itself while staying clear of the government’s red lines, balancing genuine creative expression with something palatable in a country with powerful censors.

The effort has succeeded: today, musicians say they are looking forward to an arriving golden age.

Although Chinese rap has been operating underground for decades in cities like Beijing, it is the Sichuan region that has come to dominate. The dialect lends itself to rap because it is softer than Mandarin Chinese and there are a lot more rhymes, says 25-year-old rapper Kidway, from a town just outside Chengdu.

Part of the city’s hip-hop lore centres around a collective called Chengdu Rap House or CDC, founded by a rapper called Boss X.

“When I came to mainland China, they showed me more love in like three or four months than I ever received in Hong Kong,” says Haysen Cheng, a 24-year-old rapper who moved to the city from Hong Kong in 2021.

The price of going mainstream means the underground scene has evaporated. Chengdu was once known for its underground rap battles. Those no longer happen, as freestyling usually involves a lot of swear words and other content the authorities deem unacceptable.

Then came the 2018 meeting where censors reminded television channels of who could not appear on their programmes, namely anyone who represented hip hop. PG One was finding that any attempts to release new music were quickly squelched by platforms.

But by late summer 2018, fans were excited to hear that they could expect a second season of The Rap of China. Regulators had given the go-ahead for hip hop to continue its growth in China, but artists had to obey the government censors. Hip hop had to stay away from mentions of drugs and sex. Otherwise, though, it could proceed.

“It was a success for the Chinese regulators,” Amar says. “They really succeeded in co-opting the hip-hop artists.”

The red lines have pushed artists to be more creative. But developing a genuine Chinese brand of rap remains a work in progress. Hip hop got its start in the New York boroughs of Brooklyn and the Bronx, where US rappers made music from their tough circumstances. In China, the challenge is about finding what fits its context.

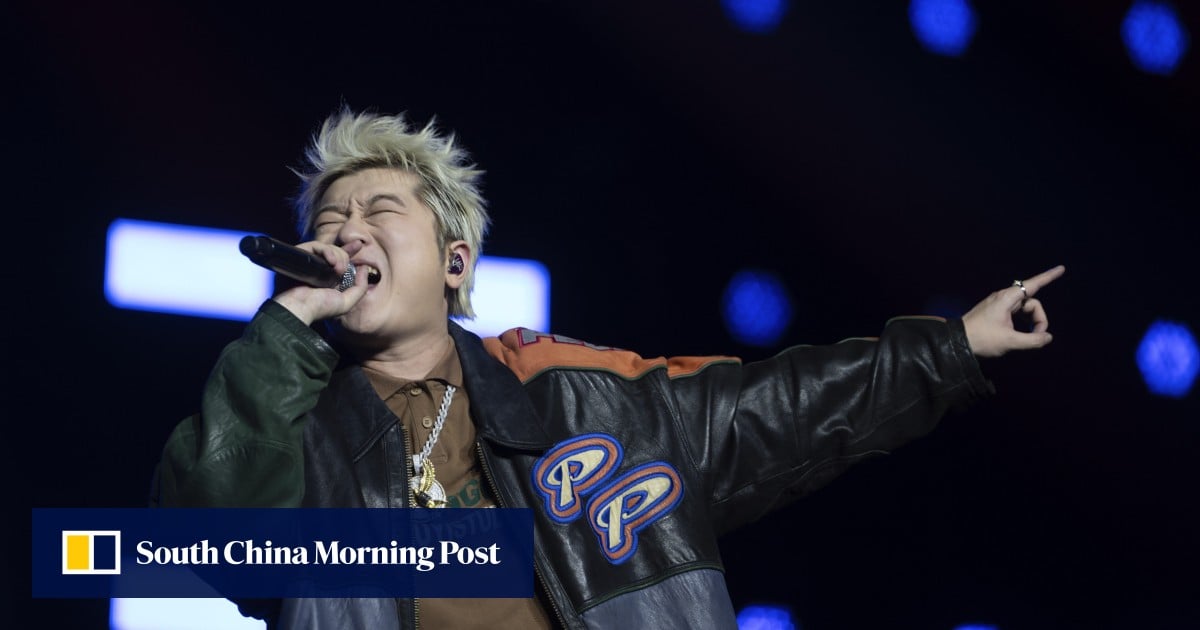

Wang Yitai, who was a member of Chengdu’s rap collective CDC, is now one of the most popular rappers in China. His style has infused mainstream pop sounds.

“We’re all trying hard to create songs that not only sound good, but also topics that fit for China,” Wang says. “I think hip hop’s spirit will always be about original creation and will always be about your own story.”