Travel

Could the airship be the answer to sustainable air travel – or is it all a load of hot air?

HAV

HAVAmid talk of sustainable aviation fuel and electric flights, there’s another form of air travel currently being mooted as a green alternative to flying: the airship.

Technically, the airship is all a load of hot air: a typically cigar-shaped, self-propelled aircraft made of a vast balloon filled with nearly weightless lifting gases, featuring an attached car or gondola for carrying passengers, crew and cargo. If it conjures up a black-and-white image of the past, you’re right – airships were popular at the beginning of the 20th Century before the rise of aviation as we know it. And now, they’re making a comeback.

Modern technological advances, paired with a need to develop the aviation industry as it struggles slowly towards net zero, have led aeronautical engineers to re-examine the airship. New materials – including new forms of ultralight nylon – developed since its heyday have made a new type of aircraft possible. Replacing flammable hydrogen with helium has allowed for safer development and aims to avoid a repeat of the Hindenburg disaster, the luxury German airship that exploded live on film in 1937. The new advances and stronger aviation standards mean that really the only thing these new airships have in common with the Hindenburg is their shape and the fact that they’re using a gas lighter than air.

Though an airship, which typically flies at around 100-130km/h, won’t ever reach the speeds of a jet plane, they are being talked about as forms of slow travel like cruise ships and night trains, where the experience makes up for the speed. Airships fly at a lower altitude than a plane, with unpressurised cabins where you can open and look out of the window, making it more comfortable for passengers. The large balloon also takes far less energy to power – and potentially could operate with electric engines powering liftoff and steering, making them a zero-carbon emitting form of air transport.

“It’s good that we are testing different ideas and innovations, as exploring various solutions is key to improving aviation and making it more sustainable in the future,” said leading aviation expert Thomas Thessen, adjunct professor at the University of Aalborg and chief analyst at Scandinavian Airlines. “The biggest advantage I can see is that they can stay in the air for a long time, and their ability to fly vertically up.”

HAV

HAVAirships do not require a runway to take off, meaning they can take off and land anywhere that has a flat space large enough for them, which could be somewhere as simple as a field, providing there is something to tether it to. This also means that they can help rescue people people in the event of natural disasters, where internet and telephony may be knocked out.

Thoughtful Travel

Want to travel better? Thoughtful Travel is a series on the ways people behave while away, from ethics to etiquette and more.

The world’s largest aircraft, the LTA Pathfinder 1, is currently being tested in Silicon Valley, California. The 124.5m by 20m new age zeppelin is equivalent in size to four Goodyear blimps and longer than three Boeing 737s. LTA – which stands for “Lighter Than Air” – is one of a handful of airship manufacturers around the world currently poised to enter the aviation market. Founded by Sergey Brin, former president of Alphabet, Google’s parent company, the company believes that next-generation airships can reduce the carbon footprint of aviation by using the helium inside the balloon to do the lifting, rather than a carbon-emitting jet engine, and using far smaller engines for thrust. Applications for their airship include more efficient cargo transport from point to point (rather than port to port); and humanitarian aid, where the airship can support relief efforts by delivering supplies even if runways, roads and ports are damaged.

They are not alone: French company Flying Whales is also currently developing airships for cargo use, aiming to reduce the environmental impact of cargo transport; while British firm Hybrid Air Vehicles (HAV) are focused on how a hybrid airship – using electric engines as well as helium – can unlock a zero-emission form of air travel.

While sustainable aviation has a long way to go to be a mass travel solution, it all adds up to a mini revolution in the skies. Along with sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) and electric planes, the new generation of airships are offering an alternative to our carbon intensive status quo of flying.

HAV

HAV“We say that the Airlander connects the unconnected,” said Hannah Cunningham, head of marketing at HAV. The Airlander 10 is their first production aircraft, a helium-filled, curvaceously shaped vehicle that wouldn’t look out of place in a comic book. It has some distinct use cases: one of them is connecting remote islands where it isn’t economical to build airports.

“You don’t need masses of infrastructure like an airport or train line with an aircraft like this – all you need is a flat surface for landing,” she said. “It opens up lots of opportunities to connect places that aren’t currently connected, for example communities in places like the Highlands and Islands in Scotland.”

Airlander 10 will have four kerosene engines, but due to the helium-filled hull, it emits 90% less CO2 than a typical aircraft. (By 2030, HAV intends to have a hydrogen fuel cell-powered electric engine and offer flights with zero emissions.) It travels at a top speed of 130 km/h and can operate as a mass passenger transport vehicle for up to 90 people.

It’s nowhere near as fast as a plane – a typical commercial passenger jet flies at 770-930km/h – but it’s not trying to replace them either. The great benefit is how it can connect places where infrastructure is too costly or passenger numbers are too few, said Cunningham.

Plans are moving forward at pace: last year, HAV signed an agreement with Spanish airline Air Nostrum to double their reservation of Airlander aircraft to 20 for passenger use from 2028, with the idea of using them to connect Spanish islands with the mainland. With a site in place to build hybrid aircraft and certification underway with the Civil Aviation Authority, they could be certified as safe to fly and going into production in four years’ time.

HAV

HAVFor Thessen, the idea that airships could fill the skies like planes is not a realistic one.

“The main thing about aviation is speed,” he said. “When you compare aviation with airships, airships travel closer to the speed of a car. In my view, airships cannot replace aircraft but might have a niche role to play, like cruise ships, on slower journeys.”

He can however see a role for it for anyone who is excited by slow travel.

“If you can put your head out of the window and get a view as you travel slowly over the landscape, I could see it having a small role as a special experience.”

In Germany, you can already try these kinds of special experiences. For around €500 for a 45-minute flight, Zeppelin offers classic Goodyear blimp airship flights over a number of cities in the Bodensee area of southern Germany, much in the mould of hot air balloon experiences.

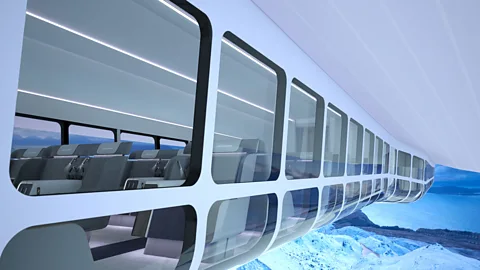

Ocean Sky Cruises are taking things one step further. The pioneering ultra-luxury airship-airline is offering once-in-a-lifetime experiences on a trip from Svalbard to the North Pole, making the most of the fact that an airship can land on ice and does not need an airstrip or an airport. The journey is expected to take two days and will be conducted at the height of luxury in an airship gondola decked out with panoramic windows, fine dining areas and opulent cabins containing eco-luxury beds that take in the views of the icebergs as you go.

Ocean Sky Cruises

Ocean Sky CruisesCabins for the extraordinary experience are selling at around US$200,000 – and they are selling so well that the only seats left are on a waiting list basis, despite the fact that there are no current departure dates and the aircraft for the voyage (expected to be the Airlander 10) has not been certified to fly, let alone purchased. Future plans include a route following the Tropic of Capricorn from Namibia’s Skeleton Coast to Victoria Falls on the Zambia-Zimbabwe border, flying low and slow over extraordinary landscapes and wildlife, and stopping in locations hard to reach by plane. Theoretically, it sounds incredible; practically speaking, there is a long way to go.

The airship sector is still in its very early stages, and much could blow it off course. Will airships go the way of flying taxis and run out of money before they can get off the ground? It’s certainly possible. But Brin’s LTA at least seems to have the capital to make their cargo and humanitarian aid plans a reality; and with buy-in from airlines and other investors, HAV is moving ahead with plans to have its hybrid aircraft in the air in the next decade, with potential to connect remote communities currently under-served by airlines.

For those of us who love to travel, green innovations in the sector are certainly a good thing, however niche. As Cunningham says, “If we want to keep exploring the world the way we do now, we don’t want to be destroying it as we do.”