The Puget Sound region did not escape the CrowdStrike-caused computer outage earlier this month. The consequences for area companies, hospitals and governments were severe. Two of the top five Big Tech outfits — Microsoft and Amazon — were among the victims.

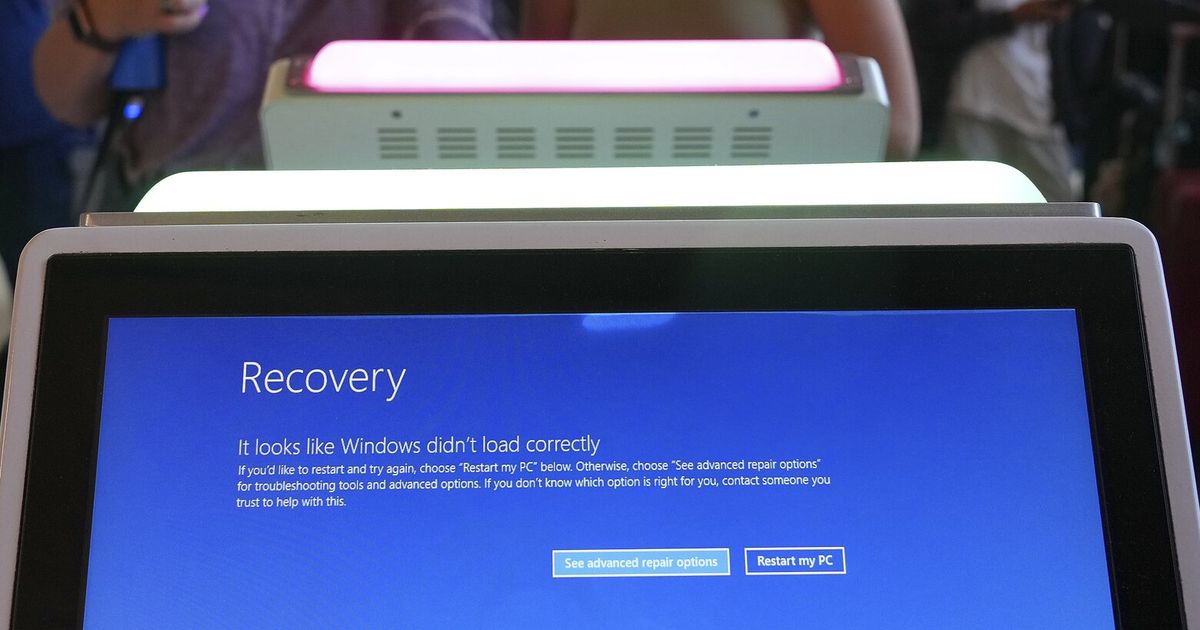

What The Wall Street Journal called, “the software patch that shook the world,” hit Windows-based computers across the planet.

It took less than 80 minutes for a fluky software update to transmit itself into Windows-based computers before CrowdStrike, a cybersecurity firm headquartered in Austin, Texas, shut it down. This was one of the largest information technology failures in history.

Microsoft estimated it affected 8.5 million devices.

Soon after the event, Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella posted on the social media platform X: “CrowdStrike released an update that began impacting IT systems globally. We are aware of the issue and are working closely with CrowdStrike and across the industry to provide customers technical guidance and support to safely bring their systems online.”

Among the consequences: Laptops at offices and homes were useless, and 911 call centers in many places were disturbed, while tens of thousands of flights were canceled; restaurants, hospitals and media companies were rattled; and employee emails at Amazon were inoperable.

Seattle-Tacoma International Airport was largely unharmed.

In some cases, CrowdStrike and Microsoft worked with companies, governments and organizations to restore service quickly. Yet in other situations, it might take months for the infected systems to be restored to their normal functions.

Delta Air Lines still hasn’t fully restored its system as I write. The U.S. Transportation Department has opened an investigation into Delta’s handling of the situation and treatment of passengers.

In addition to the disarray from the CrowdStrike issue, a different quandary affected Microsoft’s Azure cloud computing system the day before — this caused trouble for some U.S. airlines along with users of Microsoft 365 and Xbox.

Apple and Linux systems were untouched, as were servers and PCs that weren’t on the internet or turned on.

In the Puget Sound region, as my colleagues Paige Cornwell and Alex Halverson reported, the effect of such a seemingly minor update “speaks to the interconnectivity of everything,” according to Marshall Lux, a cybersecurity expert and visiting fellow at Georgetown University’s McDonough School of Business.

“In a cyber world,” he said, “the smallest thing can have huge ramifications, it can become a company’s biggest risk.”

Unlike some localities, Seattle’s 911 system was untouched by the outage.

The software CrowdStrike was attempting to update is called Falcon Sensor. If this sounds akin to a Marvel Comics character, nobody is laughing — not at CrowdStrike, Microsoft, Amazon or myriad institutions that depend on the company’s cybersecurity around the world.

“This is a very, very uncomfortable illustration of the fragility of the world’s core internet infrastructure,” Ciaran Martin, the former chief executive of Britain’s National Cyber Security Center and a professor at the Blavatnik School of Government at Oxford University, told The New York Times.

An outage such as the one caused by CrowdStrike is not a breach. A data security breach is an incident that causes unauthorized access to computer data, networks, devices or applications. One example is the ransomware attack that kept the Seattle Public Library offline for weeks.

Another is the computer virus Stuxnet that was allegedly used by the United States and Israel against Iran’s nuclear program, causing substantial damage.

Paradoxically, CrowdStrike, founded in 2011 by George Kurtz, Dmitri Aperovitch and Gregg Marston, focuses on providing online security. In 2014, the company was instrumental in uncovering Chinese industrial espionage against the United States. It also uncovered Russia’s Berserk Bear, a cyber espionage group with ties to Moscow’s Federal Security Service.

Among Berserk Bear’s activities in the United States: It was believed to infiltrate the city of Austin’s computer network in 2020.

CrowdStrike was also assigned to investigate a hack of Sony Pictures in 2014. Two years later, it was part of a probe into the hack of the Democratic National Committee, including Hillary Clinton’s emails.

Nevertheless, the latest incident is causing bipartisan outrage in Congress and a call for hearings and new oversight of cyber vulnerabilities.

Events such as this remind “Battlestar Galactica” fans of how the television show’s ship was deliberately disconnected from that civilization’s version of the internet. As a result, it survived the attack of the Cylons, sentient robots out for payback against humans.

In the real world, the outage we just experienced might well be the way World War III begins, using cyberattacks to hinder an adversary’s infrastructure, satellites and military capabilities.

All the major powers and many other nations invest heavily in cyber warfare. The United States established a Cyber Command in 2010. It’s a unified institution composed of the cyber warriors from the Air Force, Army, Navy and Marines.

China, too, has invested heavily in cyber strategies, including using between 50,000 to 100,000 people in a “hacker’s army” for espionage, potential sabotage and the ability to incapacitate the cyber capabilities of adversaries should war come.

It’s enough to make one unplug from the internet and read physical newspapers and books, lead a quiet life. But that’s not now how most of us are wired. We live in an interconnected world, like it or not. And the Seattle area is at the heart of the battle to keep it safe and operating.