Fitness

Cycling Towards Confusion: Is there room for iFIT Fitness Services and iFIT Safety Glasses?

by Dennis Crouch

In its initial decision, the TTAB dismissed iFIT’s opposition to ERB’s I-FIT FLEX registration — finding no likelihood of confusion because the goods were in separate markets. iFIT is a major manufacturer of exercise equipment like treadmills and stationary bikes and holds several trademark registrations for IFIT marks covering fitness machines, online fitness training services and content, software, and some ancillary products like apparel. ERB Industries applied to register I-FIT FLEX for protective and safety eyewear sold at hardware stores such as Home Depot. Although the two brands are at-times sold in the same online store (Amazon.com and Walmart.com) this type of overlap was not sufficient for the TTAB. In its decision, the TTAB rejected iFIT’s relatedness argument using an analogy to racecar drivers and chemists. The TTAB reasoned that while some racecar drivers and chemists may use safety glasses, that doesn’t mean safety glasses are related to racecars or to chemicals like ammonia.

iFIT appealed the Federal Circuit, and most recently Federal Circuit granted a remand request from the USPTO who acknowledged potential deficiencies in the TTAB’s factual findings on the relatedness of the parties’ goods and services and in the weight given to the similarity of the marks in light of the Federal Circuit’s recent decision in Naterra International, Inc. v. Bensalem, 92 F.4th 1113 (Fed. Cir. 2024).

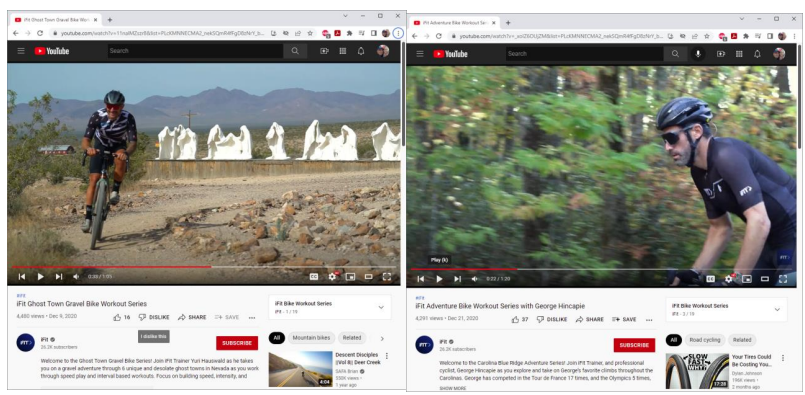

Although iFIT does not sell safety glass – or even sunglasses, it still argues that its cyclist customers were an overlapping customer group who bought both parties’ products to use together, i.e. using safety glasses while cycling. Specifically, iFIT contends that it actively markets its fitness training services and exercise equipment to cyclists. It presented evidence that cyclists discuss in online forums purchasing inexpensive safety glasses, even from hardware stores, to use while cycling. iFIT also submitted images from its own marketing materials showing iFIT cycling instructors wearing safety glasses while providing cycling-related training sessions. According to iFIT, this demonstrates that the same consumers, namely cyclists, are purchasing both iFIT’s fitness services and ERB’s safety eyewear, and then actually using the safety glasses in conjunction with the fitness services. Therefore, iFIT maintains that the TTAB erred in finding no meaningful overlap between the parties’ respective customer groups.

In its briefing, iFIT particularly focused on DuPont factors: fame, relatedness of goods/services, and overlap of customers.

- Regarding fame, iFIT argues its extensive evidence of sales, advertising, market share, and media attention conclusively establishes the fame of the IFIT mark. I do have to admit here that I’ve never heard of this brand…

- On relatedness, iFIT contends the TTAB ignored evidence showing iFIT’s fitness training services are not limited to indoor training on its machines but encompass outdoor training for cyclists. It argues ERB’s broad “safety eyewear” description encompasses all safety glasses including those used by cyclists, so cyclists represent an overlapping customer group who buys iFIT’s training services and ERB’s glasses to use together while cycling, making the goods related.

- On overlapping customers, iFIT reiterates that the evidence conclusively shows cyclists are a key overlapping customer group for the parties’ products. It argues the TTAB improperly focused only on potential overlap among indoor cyclists and disregarded evidence of overlap with outdoor cyclists.

In the end, the Federal Circuit will probably vacate the TTAB’s decision and remand for further proceedings consistent with its rulings on the legal errors regarding fame and the weight given to key factors. On remand, if fame is established and given more weight along with mark similarity, it will be a much closer case and harder to justify a finding of no likely confusion. But the TTAB could still reach the same ultimate conclusion depending on how it reweighs the evidence on relatedness and overlapping consumers. The Federal Circuit’s decision will provide important guidance on the proper treatment of fame evidence and the weight to be given to mark similarity in the likelihood of confusion factors.

The briefing cites to Naterra International, Inc. v. Bensalem. In that case, the Federal Circuit similarly vacated and remanded a TTAB that had found no likelihood of confusion between Naterra’s BABY MAGIC mark for toiletry products and Bensalem’s BABIES’ MAGIC TEA mark for medicated tea. The Federal Circuit found that the TTAB erred in its analysis of several of the DuPont factors for assessing likelihood of confusion.

- TTAB failed to properly consider evidence that several third-party companies sell both baby ingestible products and baby skincare products under the same brand. The court stated this type of “umbrella branding” evidence was relevant to assessing the relatedness of the goods under the second DuPont factor.

- TTAB’s conclusion that the trade channels were dissimilar was not supported by substantial evidence, as it ignored Bensalem’s admission that the parties’ products were sold in similar trade channels.

- TTAB should have weighed the similarity of the marks factor more heavily in favor of confusion, as the marks were highly similar and the generic term “TEA” in Bensalem’s mark did not sufficiently distinguish them.

The Naterra decision obviously is relevant to the iFIT v. ERB dispute. Like in Naterra, iFIT argues the TTAB failed to properly weigh evidence showing the relatedness of the goods, namely evidence that consumers in the overlapping class of cyclists purchase both iFIT’s fitness training services and ERB’s safety eyewear to use together during cycling. iFIT also contends, like in Naterra, that the TTAB ignored key evidence regarding the overlap in trade channels. Additionally, just as the Federal Circuit instructed in Naterra, iFIT asserts the TTAB should have weighed the strong similarity of the marks heavily in favor of confusion. iFIT goes on to argue that its case is even stronger. Unlike in Naterra where fame was not established, here iFIT maintains there is extensive evidence proving its mark is famous and that the TTAB erred in discounting that evidence.