World

D-Day deception Operation Fortitude: The World War Two army that didn’t exist

Getty Images

Getty ImagesEighty years after D-Day, a look at the biggest deception operation of World War Two – the invention of an entirely fake Army group in England, with the film industry creating dummy tanks and decoy aircraft that fooled the Nazis.

The upcoming 80th anniversary of D-Day is a good time to recall the heroism and courage of the men who landed on the beaches of Normandy on 6 June 1944, the event that turned the tide of World War Two against Hitler’s regime.

But behind their success lies the little-known contribution made by men and women from the film industry. They helped deceive the enemy into thinking that the invasion was going to happen in the Pas-de-Calais, across the shortest stretch of English Channel. And even after the Normandy landings, the German High Command continued to believe that they were nothing but a diversion and that a second, bigger invasion was still to come. How did that deception, Operation Fortitude, come about?

The story goes back to autumn 1940, when Colonel John Turner began to construct decoy airfields to confuse the Luftwaffe as to the size of Britain’s fighter defences. Turner had been Director of Works and Buildings for the Air Ministry, helping to construct new RAF airfields in the rapid mobilisation before war. He retired in 1939 but was called out of retirement to head a new top-secret department to build fake airfields and line them with dummy aircraft.

Alamy

AlamyAir Marshall Sir Hugh Dowding, the Head of RAF Fighter Command, was opposed to Turner’s work. He did not want resources diverted into decoys – he needed real fighters and real airbases. Dowding said he wanted “substance” not “shadows”.

However, the Air Ministry told Turner to carry on. But the problem Turner had was that the aircraft manufacturers made dummy aircraft that were far too over-engineered and complex for machines that simply had to look right to a passing reconnaissance aircraft at 20,000 feet. They were also very expensive. Turner needed to find a new supplier for his dummies. Enter Norman Loudon.

At the beginning of the 1930s, Loudon, a Scottish businessman, had bought a mansion west of London with 70 acres (30 hectares) of land. In 1932 he opened a film studio in the grounds of the Shepperton mansion. He built two large sounds stages, equipped them with the latest audio technology and built dressing rooms, wardrobes, workshops and all the paraphernalia for film making. Recognising that the transition to the Talkies was now permanent, he called his studios Sound City.

The Shepperton studios soon proved successful and by 1939 had doubled in size. Sound City attracted some of the finest film-makers of the day, such as producer Alexander Korda, director Anthony Asquith and film editor David Lean. A team of talented film technicians including designers, set dressers and carpenters had grown up to service the regular throughput of production. But the coming of war brought a major downturn in British film production. Technicians were called up and finance for movie production crashed.

Alamy

AlamyDuring 1940, after meeting Loudon, Turner realised the film industry was experienced in making sets that were entirely artificial but looked real on camera. Maybe they could build his dummy aircraft? Spotting a business opportunity to create work for the technicians who looked to Shepperton for their livelihood, Loudon bid for and won the contract to build 50 dummy Wellington and 100 Blenheim aircraft. The cost was one third of that charged by aircraft manufacturers. The RAF were delighted, Turner got his dummies and Loudon found valuable war work for his film technicians.

Meanwhile, 2,000 miles away, a new unit was created by the British Army in Cairo. Known simply as A-Force, it was led by another pioneer of deception, Lieutenant-Colonel Dudley Clarke. Clarke was a lively individual, a good raconteur and had the rather sinister ability of being able to enter a room without anyone noticing his arrival. He started to deceive the Italians and Germans as to Allied intentions in the see-saw Desert War fought across Egypt and Libya.

Some of his deceptions did not work but he learned from both successes and failures. He realised that for deception to be effective, it was necessary not just to make the enemy think something, but to do something – to leave their forces in the wrong place or to move troops away from the focus of a new attack. And he rapidly became skilful in the art of creating forces that did not exist, in exaggerating the Order of Battle. He invented a brigade of paratroopers and convinced the Italians that they would be used to drop behind their lines. But no airborne troops existed in North Africa. He went on to invent divisions and army corps to make it look as though the Eighth Army was much bigger than it was.

Alamy

AlamyAt the battle of El Alamein in October 1942, Clarke and his fellow-deceivers convinced the enemy that the thrust of the Allied attack was coming from the south of the battlefront. Trucks covered with tarpaulins that made them look like tanks from the air were drawn up, creating what appeared to be tank tracks in the sand. They laid what looked like a pipeline to an imaginary fuel depot in the south, in fact made from old oil drums. The Germans put two armoured divisions in the south to meet this apparent threat. When the battle came, Montgomery attacked from the north of the battlefront. The battle still took 10 days of heavy fighting but outmanoeuvring the enemy undoubtedly helped bring victory.

When it came to planning for D-Day, the biggest amphibious operation ever launched, the need for a detailed deception plan was even greater. When discussing the invasion with Joseph Stalin at Tehran, Winston Churchill used the phrase, “In wartime truth is so precious that it should always be attended by a bodyguard of lies.” This perfectly summed up the Allied view of deception.

General Montgomery, since Alamein a keen supporter of deception, was put in charge of the 21st Army Group, effectively making him commander of land forces on D-Day and beyond. His chief deception officer, Lieutenant-Colonel David Strangeways, insisted that the only way to make the Germans keep a large army, their 15th Army, in the Calais region was to convince them that a complete Army Group was forming in Kent, Essex and Suffolk, preparing to invade along the Pas-de-Calais. But how could the deceivers drum up an army of 300,000 men who did not exist?

There were many elements to the deception campaign known as Operation Fortitude. Double agents, German spies who had been sent to Britain and had been turned by MI5, sent back misinformation to their German minders. They played a major role. There were scientific deceptions, too, sending false signals to indicate flotillas of ships or squadrons of aircraft were somewhere they were not.

Getty Images

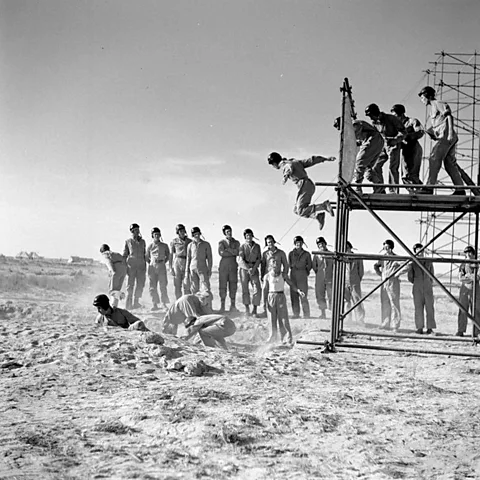

Getty ImagesBut to create a phoney army, the deceivers started with a name, the First US Army Group, known by its acronym as FUSAG. Once again, the Shepperton film technicians were put to work building dummy tanks for this pretend army. Consisting of rubber and canvas around a metal frame, they could be inflated in 30 minutes. Hundreds were produced and lined up in vast assembly areas, just like in the south-west where the real army was gathering for the real invasion. They designed large landing craft made out of canvas and wood that floated on empty oil drums. Each craft took 30 men six or seven hours to assemble. Two hundred and fifty were “launched” along the south-east coast from Dover to Great Yarmouth. Unfortunately, although moored with a heavy anchor, they had a tendency to flip over in strong wind. Companies of the Worcestershire Regiment were put on standby to rush in to turn them back upright as quickly as possible.

Additionally, a fake fuel depot was built just along the coast from Dover. Made from wooden boards, scaffolding and old sewer pipes from bomb sites, it looked unimpressive from the ground. But, crucially, from 20,000 feet it looked like the real thing.

Some existing US and Canadian divisions were allocated to FUSAG and several new divisions were invented to create the numbers involved. A complete US Army Signals unit was instructed to send phoney radio messages up and down the chain of command with details of training exercises and mock beach landings. The Germans did not need to decipher all these messages. They could see from the volume of radio traffic generated that what appeared to be a large army was gathering in south-east England. By the end of May, a week before D-Day, German Intelligence calculated that 79 Allied divisions had assembled in the UK. In fact, the number was only 52.

Imperial War Museum

Imperial War MuseumBut every army needs a commander and in a final brilliant coup de theatre, General George S Patton was put in command of FUSAG. Doubtless he would have preferred to be commanding real troops preparing for the actual invasion, but he threw himself into this new role.

As a great showman, he would turn up to make speeches and inspect imaginary infantry and armoured units. Everywhere he went, he was accompanied by photographers and his new command soon leaked out to the enemy. As the Germans thought he was one of the best generals the Allies had, they fully believed he would command the spearhead of the invasion of Europe.

When the D-Day landings took place in Normandy, they took the Germans by complete surprise. But they were quick to react and, within a few days, reinforcements had arrived from south and west France to do battle. The six-week struggle to break out from Normandy was long and hard. Yet crucially, the German 15th Army remained in the Pas-de-Calais awaiting what the German High Command was convinced would be a second major invasion.

While the decisive battles in the west were being fought out in Normandy, more than 150,000 German troops sat twiddling their fingers 200 miles (321km) away around Calais. The deception campaign, Operation Fortitude, had succeeded magnificently.