Jobs

Don’t Worry About Manufacturing Jobs. Worry About Manufacturing Productivity

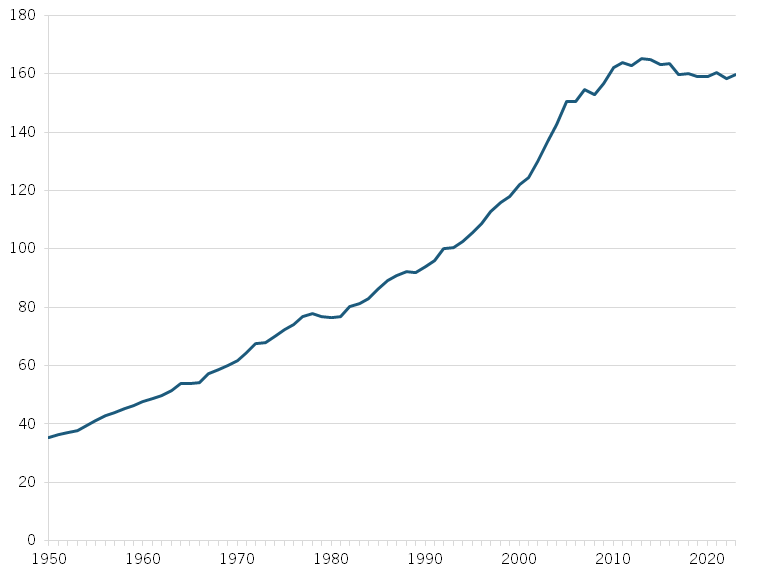

If figure 1 showed something like rates of obesity, air pollution, or violent crime, then we’d be celebrating the decline we’ve experienced since 2011. But it is a graph of the change in labor productivity in U.S. manufacturing, which grew steadily throughout the post-war era until 2010, and since then has slid. Let me say this again: U.S. manufacturing is becoming less productive.

Figure 1: Manufacturing sector labor productivity index (1992 = 100)

Does anyone think this is a problem? Anyone? Certainly, neither presidential candidate appears to care, as all we have heard from them on this issue is crickets. And the economic pundits tell us we’re in the midst of an automation boom that is disrupting the labor force: The Rise of the Robots! The Second Machine Age! The World Without Work! But it’s more like the decline of the robots, the first machine age, and a world with inefficient work. The Washington Post’s Catherine Rampell has argued that in recent years technological advances have led to huge productivity gains in manufacturing. Yeah, maybe not.

Without more detailed analysis, it’s not possible to determine the exact causes of the productivity stagnation we’re experiencing in manufacturing. It does not appear to be related to overstating output in computers and electronic equipment (although, that has been a problem), because we see the same decline in non-durable manufacturing productivity (figure 2).

Figure 2: Non-durable manufacturing sector labor productivity index (1992 = 100)

It does not seem likely that it is a measurement problem, either. After all, measuring quality-adjusted output is generally seen as harder in non-manufacturing, which has seen much higher productivity growth. Moreover, if it were a measurement issue, then what changed so decisively around 2011?

It is possible that the explanation is compositional—if more productive firms or industries are losing market share faster than less productive ones, so the less productive firms are dominating the picture. But it makes no sense that highly productive firms in a particular industry would lose market share. It is possible that highly productive sectors like aerospace could be growing slower or even declining faster than less productive sectors like textiles. But this would be an odd trend, because economic theory suggests that the United States should be more likely to lose less productive sectors to low-wage nations like China than to lose highly productive sectors.

Maybe it is technological stagnation. But if so, then it is odd that the overall non-farm business sector saw 28 percent productivity growth from 2008 to 2024, while manufacturing saw just 1 percent productivity growth.

Indeed, in the late 1980s, MIT economist Robert Solow famously said we see computers everywhere but in the productivity statistics. He might well say today that IoT, 3D printing, robotics, and AI are showing up everywhere except in the productivity statistics, because they seem to have produced more excitement than output. I remember speaking on a panel about a decade ago with an MIT professor who confidently predicted we would soon be producing virtually everything with 3D printing. It hasn’t turned out that way.

Maybe one reason for the stagnation in manufacturing productivity is that, according to the National Science Foundation, just 23 percent of U.S. manufacturers were engaged in process innovation, which improves how things are manufactured.

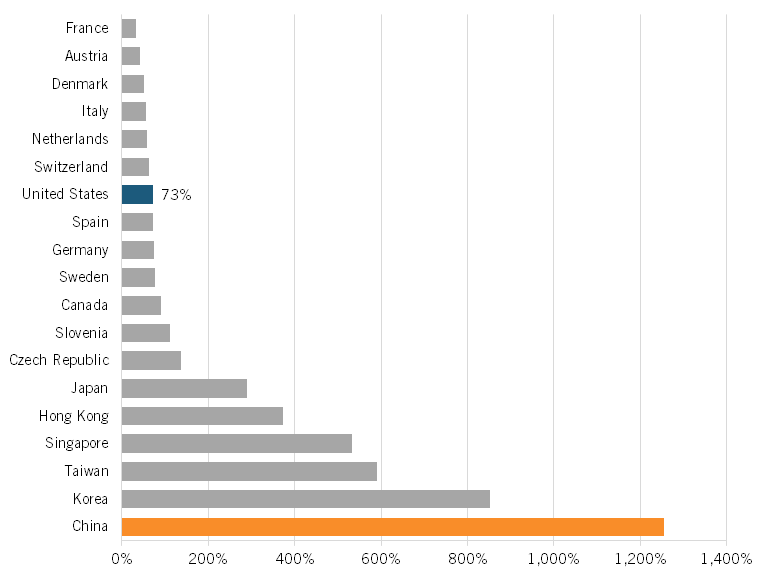

And, as ITIF has found, China leaves the United States in the dust when it comes to robot adoption, both in number of robots adopted per 10,000 workers and in wage-adjusted expectations. In fact, as figure 3 shows, China installs 12 times more manufacturing robots than would be expected given its wage levels, while the United installs only 73 percent as many as we would expect. At this rate, we could see Chinese manufacturing productivity exceed America’s in a decade.

Figure 3: Actual robot adoption as a share of expected adoption after adjusting for wage levels, 2022

And, frankly, the level of support that the U.S. government provides to incentivize manufacturing technology adoption is pitiful. Japan invests 55 times more in manufacturing support for small and medium-sized enterprises than does the United States, while Germany invests 6 times more. The equivalent U.S. program, NIST’s Manufacturing Extension Partnership program, has been starved for funds for at least a decade.

This all matters for two main reasons. First, real wages cannot grow faster than productivity growth. Second, without productivity growth (or a serious decline in the value of the dollar), U.S. manufacturing will increasingly find itself at a competitive disadvantage.

So, what to do? Four things:

1. Wake the heck up and take this challenge seriously.

2. Congress should institute a temporary 25 percent investment tax credit lasting six years to spur a surge of investment in new machinery, equipment, and software in the United States.

3. Establish a network of five or six automation institutes across the nation that focus on helping U.S. manufacturers automate work and boost productivity.

4. The Department of Commerce should support a research project to investigate the sources of U.S. manufacturing stagnation. (Something that is its job anyway.)

Oh, and one other thing: Stop whining about potential job losses. As one Swedish trade union official said to me once: “In Sweden, the unions don’t worry about companies investing in new technology. We worry about them holding onto old technology—because, if they do that, then they are likely to go out of business.”

Amen. Let’s get to work.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24100829/226345_Nest_Doorbell_wired_JTuphy_0006.jpg)