World

Footballers to compete in 50°C heat at 2026 World Cup, study warns

The 2022 World Cup was held in Qatar between November and December, with many matches scheduled at night to avoid the extreme heat. The next World Cup, set for 2026, will take place in Canada, the United States, and Mexico, between June and July. However, a biometeorological report published in Scientific Reports warns that many of the venues in 2026 face a high risk of excessive heat. In three of the venues, extreme heat stress could persist well into the afternoon, potentially reaching temperatures of up to 50ºC (122ºF). In the context of climate change, the report’s authors argue that measures will be needed to protect players from decreased performance or, in the worst case, health issues. Looking ahead to 2030, the World Cup will be held during the summer in countries like Morocco, Portugal, and Spain, which are also known for their high summer temperatures.

A few years ago, the International Federation of Association Football (FIFA) introduced several measures to safeguard players’ health under extreme weather conditions. The most well-known of these is the hydration break, where players pause the game for three minutes to rehydrate and replenish the water and salts they have lost. These breaks can be activated after 30 minutes into each half of the match if the temperature reaches 32ºC (89.6ºF). However, this temperature is not measured by a conventional thermometer, but by a more complex instrument that calculates the Wet Bulb Globe Temperature index (WBGT). The WBGT combines temperature, relative humidity, wind, and solar radiation into a single value, which is considered to more accurately reflect the perceived heat — how the body experiences it. Despite this, the authors of the new report argue that the WBGT index does not fully capture the thermal stress experienced by players.

“Although FIFA recommends using the WBGT index to determine safety standards during a soccer match, it is considered an imperfect measure of the heat load of athletes, as it tends to underestimate the level of heat stress,” says Marek Konefał, a sports physiology researcher at the University of Wrocław in Poland and senior author of the Scientific Reports study. “The WBGT does not incorporate the most important factors specific to sport, namely the production of specific metabolic heat, the specific clothing worn by athletes and the effects of body movement on relative air velocity,” he adds.

What’s more, this index does not accurately reflect the additional heat load caused by environmental factors like high humidity or insufficient airflow, which interfere with the body’s primary cooling mechanism — sweating. For these reasons, Konefał and his colleagues have proposed an alternative indicator: the Universal Thermal Climate Index (UTCI). In addition to incorporating all the factors included in the WBGT, the UTCI adds parameters that better model the human body’s response to heat.

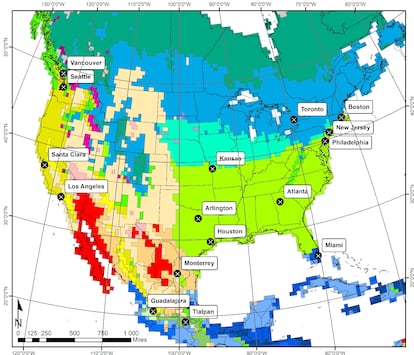

Based on the UTCI, 10 of the 16 planned World Cup venues could put players at risk of extreme heat stress, with the most dangerous matches expected to take place in Arlington and Houston (both in Texas) and Monterrey, Mexico. The highest levels of heat stress will occur between 14:00 and 17:00 local time in all venues, except for Miami, which will move its time slot earlier to between 11:00 and 12:00. One of the key factors contributing to heat stress will be dehydration. According to climate data recorded by the European Copernicus system in June and July since 2009, the greatest risk period will again be in the early afternoon. On the fields in Arlington, Houston, and Monterrey, players could lose more than a kilogram of sweat (essentially water) in just one hour. The mildest locations will be Vancouver, Seattle, and Tlalpan. The first two are located far to the north, while the latter is situated more than 2,200 meters above sea level.

“UTCI values do not correspond to exact air temperature data, as they reflect the combined impact of air temperature, humidity, wind speed, solar radiation, physical activity, and clothing on the human thermoregulatory system and the heat exchange between the body and the environment,” Konefal explains.

According to his calculations, three venues — Arlington, Houston, and Monterrey — could experience UTCI temperatures of 49.5°C until as late as 18:00, which would cause extreme heat stress for the players. However, Konefal does not believe these venues should be excluded from the tournament, but rather suggests matches be scheduled at safer, more suitable times. He also emphasizes the need for air-conditioned facilities throughout the stadiums and concludes with a thought that could prove timely for future World Cups: “Given the increase in global temperatures, perhaps the World Cup should be moved to spring or autumn.”

Pedro Antonio Ruiz, a personal trainer and professor at the Faculty of Sports Sciences at the University of Murcia, recalls that in conditions of high temperature and humidity, “we generate a lot of heat, but the humidity prevents us from dissipating it.” This is expected in many of the World Cup venues. “When both thermal conditions coincide, the risk of dehydration and even heat stroke increases exponentially, as it is normal for players to lose between 2-3% of their body weight during a match,” he explains.

Thermal stress begins at 24º-25ºC (75.2ºF-77ºF), “but playing at the 35ºC [95ºF] that will occur in many of these cities is crazy,” adds Ruiz. While tournament officials are taking precautions, such as extending cooling breaks and scheduling matches with heat risks in mind, Ruiz fears that high temperatures and humidity will remain a challenge even in the later hours, from 20:00 to 22:00.

Another issue that Ruiz emphasizes is the altitude. With two venues situated at higher elevations — Tlalpan (2,240 meters) and Guadalajara (1,566 meters) — ”a period of acclimatization will be needed; arriving the day before the match will put you at a disadvantage,” he says. This is because players or teams not accustomed to exercising at altitude, where oxygen levels are lower, “will compensate for the reduced O₂ in the air by breathing more intensely, leading to a forced decrease in performance during the match,” he explains. For Ruiz, holding World Cups in two or three countries is not inherently problematic from a health perspective. However, “the combination of countries complicates matters; while the three are contiguous, they have different climatic zones.” In fact, the 16 venues are spread across nine distinct climatic zones.

David Jiménez Pavón, head of the MOVE-IT research group at the University of Cádiz in Spain, further explains the physiological effects of high temperatures and relative humidity: “Performance is significantly reduced due to changes in different physiological elements. Even if athletes maintain high levels of hydration during physical activity, there is usually not enough time to achieve the required hydration ratio.” To keep the body temperature in balance, “an accelerated process of sweating, hemoconcentration, and an elevated heart rate occurs… in short, anaerobic metabolism is triggered more,” he adds. This, in turn, “generates more lactic acid, which is clearly linked to the onset of fatigue earlier in performance.”

Jiménez advocates for prior testing of players’ physical condition: “It would be highly advisable for athletes and footballers to undergo thermal stress performance tests to assess how they individually respond and adapt to these physiological challenges in high-level competition.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/70-year-old-aunt-solo-travel-devices-tout-110183be0ec9417d8cfc243204980446.jpg)