World

Fundamental Tactics: How To Handoff | Sailing World

Illustration by Kim Downing

We are on port coming into the windward mark, and I know that the rules are not in our favor. “The starboard layline is crowded; it’s going to be messy,” my tactician tells me. I take a quick look ahead and to leeward to size up the situation, and indeed, it does look dense. Oh, boy. I return my focus back to sailing fast, absorbing what I just saw. Getting closer, my tactician paints the picture. “You have three boats to worry about: Bow 72 is short of layline, then bow 54 is on a tight lay, and 16 is overstood.”

I take a longer look to leeward, identifying those three boats as he continues, “It looks like you will cross 72, likely you will have to duck 54, then tack below 16.” Followed by, “It’s yours.”

“It’s yours” is a simple and clear explicit handoff from our tactician to me, the driver. Now it’s mine to execute. It needs to be mine, because in these moments, things are happening quickly, requiring split-second decisions with no time for our tactician to micromanage. Besides, the driver is the only one who can possibly know what can and cannot be done within the inches that are necessary for success.

“Copy” is the required response, but it alone is not quite enough. “Copy, I’ll get past 72 and 54, then tack below 16” confirms that I indeed got the message, putting our whole team at ease. But if I missed something, it gives a chance for my tactician to correct me.

The explicit “It’s yours” and “Copy” handoff routine is peppered throughout the race as necessary, but during starts and mark roundings, the driver always takes the lead. These are implicit handoffs because it is always that way.

For starts, this implicit handoff begins at the warning and remains for the rest of the sequence. Because speed is not our primary concern during the sequence, I have plenty of bandwidth to focus on positioning and boat-on-boat tactics. Although ultimately it’s my responsibility, and I know I will have to make quick decisions, there is plenty of time for conversation. We constantly discuss things such as our distance to the line, finding just the right place to make the final tack, and how best to defend our hole. It’s a careful balance, and the tactician needs to know when I need to be left alone to execute without distraction, and when it is appropriate to interject. For example, when we are on the starboard-tack final approach to the line, if all is going to play, the tactician is mostly quiet. But if my time and distance are off, or someone is trying to poach our hole, the tactician better chime in and help.

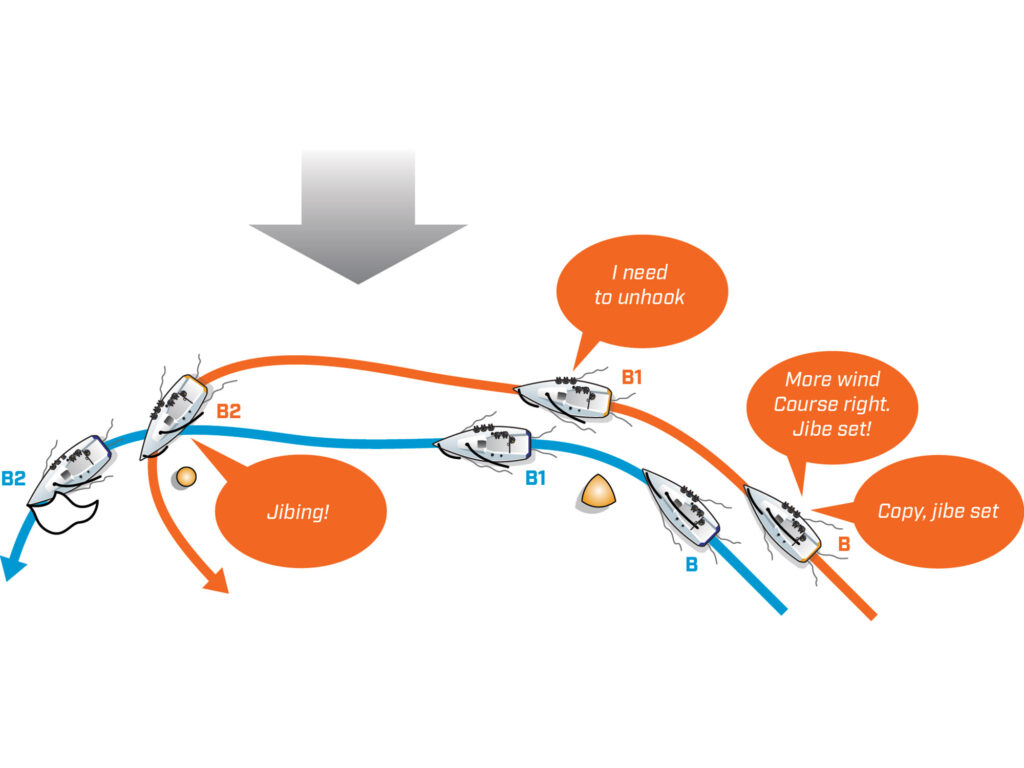

At marks, the handoff happens just as we are about to round the mark. Unlike the start, where there is conversation, there is usually no time and I need to be left alone. To do that, I need to know the plan from my tactician well ahead of time. For example, before we enter the fray at the windward mark, I need to know if we want to do a straight set or jibe set.

If the tactician says, “We want to jibe as soon as possible after the offset,” he’s telling me that my job is to position our boat on the inside on the offset leg so that we can pull off a jibe. “Straight set” tells me to defend high. Even though it is implicit, the handoff can begin early, such as our example where the tactician paints the picture of the crowded starboard layline, then explicitly hands off the execution well before we get to the mark.

Occasionally I will take control when something unexpected happens and there is not time for my tactician to say, “It’s yours,” let alone paint the picture. This can happen because the tactician failed to look ahead, plan, and communicate.

“If bow 54 tacks, lead them back” prevents this sort of surprise. But something totally unusual could happen, such as a boat that capsizes in front of us, or their skipper drops the tiller and spins out. Either way, I will have to make my own quick decision, with no time for a handoff.

Similarly, anyone can chime in to avoid disaster. When I hear “Crash tack!” or “Duck hard!” from any team member, I react immediately, with no questions asked. Yes, it will be a bad tack or duck. The trimmer will need to sort out the jib, and all those hiking need to struggle to the new side, but it beats the alternative.

Whether explicit or implicit, the handoff is binding and absolute; only one person can be in charge. For example, if I hear, “Duck if you can’t cross; we want to continue on port,” and I respond with, “Copy, ducking if I can’t cross,” I can’t have any micromanagement from my tactician or anyone else because it’s too distracting. Likewise, when it is not my turn, my tactician is the boss, and aside from infrequent constructive information, I need to just do my job and drive fast.

Whenever I finish my duck, round the mark, or whatever the maneuver is, I don’t say something like “Back to you” to hand back the reins. It’s not necessary because it’s obvious to all when the maneuver is done. But I do like when the tactician makes it clear that they have things in hand, like, “We are still lifted on the long tack, no traffic and no plans to tack anytime soon.” That makes it super-clear that they are back on task and puts my mind at ease.

Other team members have important strategic and tactical support roles, and it is important to acknowledge that. Someone might help the tactician look for wind in the distance, while someone else is reading the compass. A collaborative tactician is a good tactician. I have a smile on my face when I hear the team debating what to do next. But there can’t be more than one boss at a time—it’s either the tactician or the driver. Input is fine, but the rest of the team can’t confuse the situation by making calls.

Illustration by Kim Downing

In rare circumstances, I will override my tactician. I recall a scenario where the tactician could not find the new mark and insisted it must be on the right side. But I could sense uncertainty and frustration, and my gut had a strong feeling that we had been on port way too long. I recall saying, “Sorry, I just need to tack and center up while we look,” as I pushed over the helm to lead a clump of boats back. This is a touchy thing to do; it is not a good thing to undermine your tactician. My tactician has a phrase: “If you override me, you’d better be right!”

I don’t take “you’d better be right” to be literal; it’s just a phrase we use to put it in perspective. When I override, one of us will be wrong. If the mark indeed was to the right, I will be wrong. If it was more centered up, my tactician would be wrong. But neither of us should look at it that way; we both need to be empowered to make decisions and with that, to fail. Strategy and tactics are inexact, and I expect mistakes, even when we are on top of our game. The teams who move on and quickly work on what to do next are the teams who succeed.

I regularly sail a singlehanded boat and often verbally hand off to myself. That might sound silly since I am the tactician and make all the calls, as well as the driver with all the power to execute. But it is a mental cue for me. I need to shift my concentration from speed to tactics and back, which is not easy to do. Saying the handoff out loud helps me define the priority of the moment.

Sailing fast is a driver’s best contribution to tactics because, as it’s widely accepted, nothing makes a tactician look smarter than boatspeed. I am in charge implicitly at the start and mark roundings, and explicitly when handed to me at scattered moments throughout the race. The rest of the time, knowing that the tactician is fully in charge, I put my head down and go fast. I must admit, I look forward to hearing, “It’s yours,” as a welcome break from staring at my telltales. “Copy,” I’ll respond while looking around to assess the situation. I’ll finish that maneuver and then, refreshed from the break, focus once again on going fast.