Jobs

Growth In Government Jobs Points To Recession

ronniechua

By Ryan McMaken

Last week, we looked at the weakness of the job market that belies all the happy talk from the administration about employment. For instance, we noted the fact that full-time employment is in decline, as is temporary work. We can couple this with the fact that the total number of employed persons in this economy has gone nowhere in eleven months.

On top of all this, another indicator of the lackluster jobs economy is the volume of government job growth compared to private sector job growth.

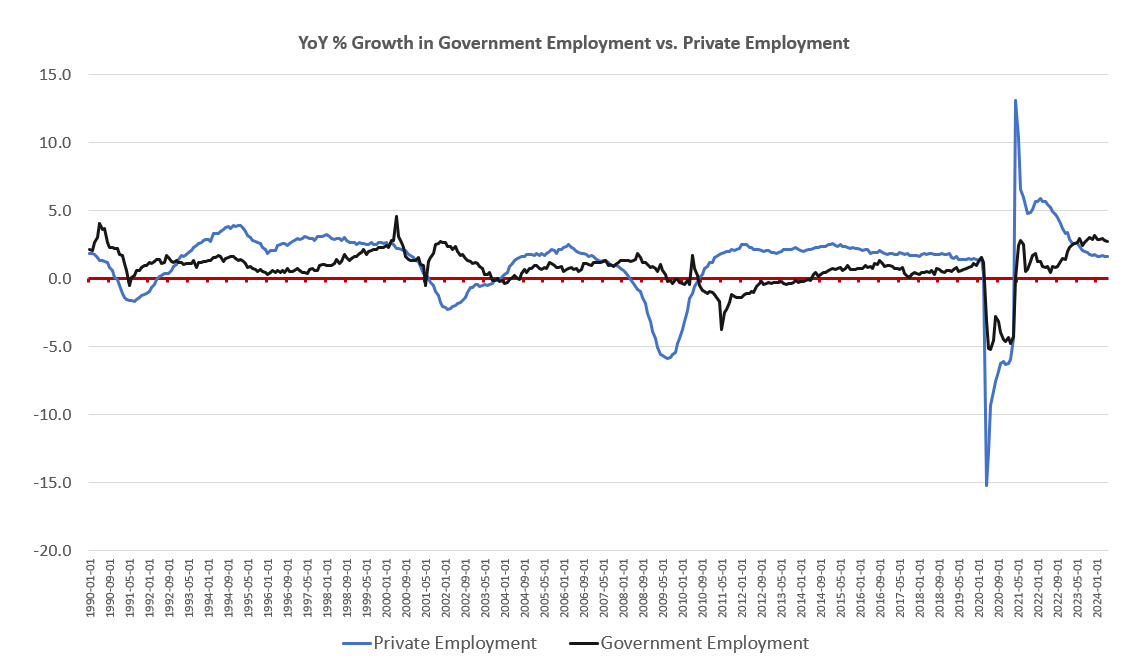

There are a couple of ways to look at this. The first is to look at growth in government jobs versus growth in private employment over time. In this case, we see that since March of 2023 government employment has been growing faster than private employment.

Last month, for instance, government employment was up 2.7 percent, year over year, while private employment was up 1.6 percent. Growth in government jobs has been outpacing private employment (year over year) for the past fourteen months. We can see this in the graph:

Another thing jumps out at us when we look at the graph. Namely, periods when government jobs grow faster than private jobs are periods with weakening economic conditions.

For example, we find that government employment outpaced private employment in 1990 in the lead-up to the early-1990s recession. We find a similar trend develop during 2000, as the dot-com bust approached.

The trend again appeared in late 2007 right before the Great Recession began. Notably, we also find that overall job growth remained positive as this trend developed. Actual overall job losses came only after several months of government employment outpacing private employment.

Essentially, the current trend in this metric points to the US now being in recession or headed towards one soon. Another way to view this trend is to look at what proportion of new jobs created are government jobs.

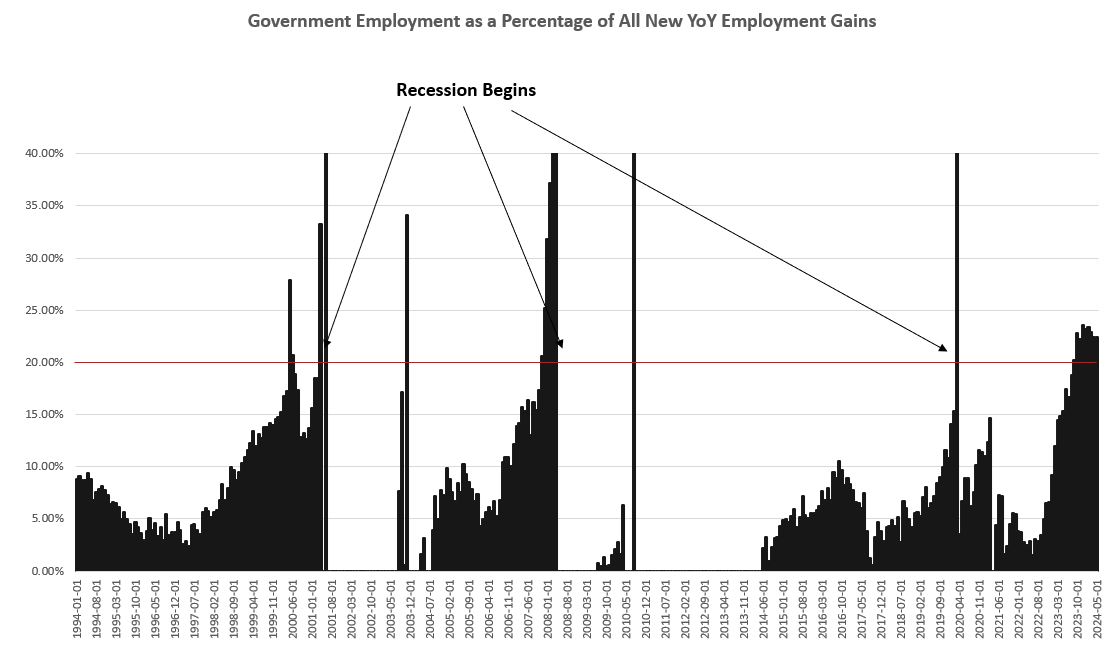

In this case, we find that government jobs have made up more than 20 percent of newly created jobs for the past nine months. Or conversely, we can say that less than 80 percent of new jobs are private jobs.

This is significant because when we look at historical trends, we find that in periods where private employment fell below 80 percent, the economy was headed toward recession. This is true in every recession for more than 35 years.

Most recently, it was clearly the case in the run-up to the Great Recession, as can be seen in the graph. In 2008, we find that government jobs grew quickly as a proportion of all new job growth as the recession approached in 2008.

A similar trend appeared in the run-up to the dot-com bust as well. With growth in government employment now up over twenty percent of all job growth in recent months, it is reasonable to suspect an approaching recession.

Of course, whatever the timing of the next recession may be, it is clear the jobs economy is hardly “strong” as claimed by the Biden Administration and its supporters.

Rather, one-fifth of all new job growth – assuming one even believes the questionable establishment survey numbers – are government jobs that are paid for by new private sector workers.

This “job growth” is largely government spending enabled by immense new government deficits that are now being racked up. (The federal government now admits this deficit will reach around two trillion dollars this year.)

This reminds us of Daniel Lacalle’s description of the economy as one where the private sector is in recession while the government sector is in a boom. Immense government spending – spending financed by debt, of course – drives up GDP numbers, but, as Lacalle points out, this GDP growth hides deterioration in saving and investment.

In other words, the private economy is facing rising prices and deteriorating capital while the government sector keeps spending wildly. The fact that government employment is an increasingly prominent part of total job growth should not surprise us.

Editor’s Note: The summary bullets for this article were chosen by Seeking Alpha editors.