World

How Apple Rules the World

Businessweek | The Big Take

The world’s most valuable company is loved, and feared, because of the fanatical control it maintains over the iPhone. How long can that last?

The legacy of the 1984 Super Bowl is an underdog story, but not the one on the field. During the third quarter, as 80 million football fans watched the Los Angeles Raiders pull away from the Washington Redskins, the defending champions, a commercial showed a column of uniformed men with gray faces and shaved heads marching into a theater. There a looming Big Brother figure on a giant telescreen shouted about the “glorious” unification of society into a “garden of pure ideology.” That was until a young woman sprinted forth and hurled a sledgehammer through the screen, silencing the dictator. “You’ll see,” a narrator intoned, “why 1984 won’t be like 1984.”

It’s a damn good ad. Source: Apple

This ad, for Apple’s first Macintosh, would go on to become one of the most famous commercials of all time. Its director, Ridley Scott, reframed computers from boring business tools into statements of identity. Co-founder Steve Jobs and other early Apple executives saw themselves as rebels and artists. Steve Hayden, who helped conceive the ad and worked closely on it with Jobs, says the Mac “was supposed to be an empowering device” that put technology in the hands of regular people instead of corporations and governments. Four decades later, the disruptive power of personal computing has gone from revelation to cliché, and Apple is widely understood to have helped democratize information by defining the PC and its successor, the smartphone.

One side effect of this influence, however, is that Apple is no longer the plucky rebel taking on the evil empire.1 These days, critics argue, Apple is the one using technology to entrench its power, and the face of Chief Executive Officer Tim Cook is the one looming from the telescreen.

Apple Inc. is worth $3.4 trillion, more than any other company in the world. Its 2023 revenue (almost $400 billion) makes it about as big as the entire economy of Denmark or the Philippines. And though most of the business, as you’d expect, revolves around selling iPhones, it’s also grown far broader. Last quarter, Apple’s sales from digital services alone reached $24.2 billion, more than the combined revenue of Adobe, Airbnb, Netflix, Palantir, Spotify, Zoom and Elon Musk’s X.

Amazingly, these figures understate the company’s influence and power. Through its App Store, Apple tightly controls enormous platforms for digital communication, mobile finance, social networks, music, movies, transportation, news, sports and pretty much anything else that happens in 1s and 0s, which is to say, everything. This software ecosystem, Apple’s own version of the garden of pure ideology, is accessible only to those who comply with the company’s rigorous store policies and related “Human Interface Guidelines,” its content standards, and its tolls. When money crosses through this system, as it does constantly, Apple gets as much as 30%. Every time you wave your iPhone or Apple Watch at a credit reader in the real world, Apple gets a small cut of those transactions, too.

For companies of a certain size, there’s no real way to get out of paying what’s become known as the “Apple tax.” That’s partly because Apple customers are loyal, but it’s also because there’s really only one other smartphone app store, on Google’s Android platform, and it imposes similar fees and restrictions. And even Google pays Apple, turning over a cut of the ad revenue it generates on the iPhone as part of a deal that kept Google as the default search provider on Apple’s mobile web browser. The payments have amounted to $20 billion per year.

There was a time when buying a computer meant paying for a piece of hardware you owned outright. Now it means purchasing an extremely expensive device (at least $1,000 for the most advanced iPhones) and then spending hundreds of dollars on subscriptions and other add-ons that are optional but increasingly seem required. There’s AppleCare+ for when you crack the screen, iCloud to store your photos, plus monthly charges for songs, fitness classes, TV shows and video games. Magazines, too: You can read this article on Bloomberg.com, but you can also get it by subscribing to Apple’s news service.2 After reading this article on your iPhone, you might turn back to your work on a MacBook, stream Apple-produced films on an Apple TV player, read a book on your iPad, or go for a run with an Apple Watch and a pair of AirPods. Later you can even strap on an Apple Vision Pro headset so you never have to experience reality unmediated by a designed-in-Cupertino filter.

Investors, as a general rule, have no problem with this kind of dominance, as Apple’s soaring stock price over the past decade makes clear. Regulators, on the other hand, have some questions. In March the US Department of Justice filed a sweeping antitrust complaint accusing Apple of anticompetitive practices that have essentially locked consumers and partners into its ecosystem, extracting ever larger sums from both groups. The antitrust complaint is long, and complex, but it boils down to a point that will be familiar to the company’s critics. As one former executive, who like other ex-employees spoke on condition of anonymity for fear of retaliation, puts it, “They’re starting to become Big Brother.” Apple, as in similar antitrust cases filed in other countries, has denied wrongdoing and has said its success comes from creating innovative products that are easy and fun to use, especially together.

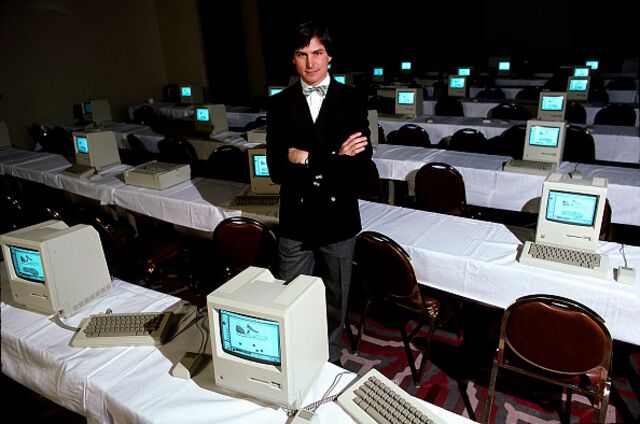

Jobs with the original Macintosh. Photographer: Michael L Abramson/Getty Images

“We bring the same pioneering, adventurous spirit to that mission we always have, and we only make products that empower people and enrich their lives,” a company spokesperson said in a statement. “People choose Apple products because they love them, they trust them, and they use them every day.”

The US proceeding gained greater urgency in August, when a federal judge ruled against Google in a separate case that hinged, in part, on its default search agreement with Apple. (Google has said it will appeal.) Taken together, the two cases raise questions about how we look at some of the world’s most successful tech companies. How did businesses that were once widely seen as counterweights to corporate dominance find themselves in positions of otherworldly power and influence? And how did Apple, which has long considered itself an advocate for free expression, get accused of the same Orwellian tactics it once mocked? Does Apple’s power derive from the strength of its beloved products or from the way the company designed those products to lock out competitors?

The answers have implications for Apple shareholders. The company is facing disputes with a growing list of partners, including banks, filmmakers, car manufacturers, app developers and customers who’ve begun to doubt that Apple is still the creative force they fell in love with years or decades ago. The implications for the rest of us non-shareholders are just as significant. More than ever, and very much by design, we’re all living in Apple’s world.

Ironically, Apple’s early success came from its openness. Although the Mac ran on an operating system that theoretically limited what outside developers could do, in the heyday of the floppy disk, there were few restrictions and little oversight. Aldus Corp. founder Paul Brainerd, whose PageMaker software is credited with saving the $2,495 Mac from being dismissed as an expensive toy, says he doesn’t even remember seeing a copy of Apple’s original Human Interface Guidelines back then. “An Apple sales rep showed up at our office with two Macs in his truck and said, ‘Here, take these and do whatever you want with them,’ ” recalls Brainerd, who soon coined the term “desktop publishing.”3

Jobs, who championed firm control over Apple’s integrated hardware and software,4 was pushed out in 1985, the year of PageMaker’s release. When he returned 12 years later, he desperately needed developers to make things for the new iMac, and the company’s control stayed loose for a while. At an Apple event in New York a month before the iMac’s release in 1998, Jobs bragged that the company had amassed 177 third-party apps. By the standards of today’s Apple, this was minuscule; at the time, Jobs called it a “huge” milestone.

As the company’s products became more popular, its relationships with developers started to change. In the early 2000s, Apple thwarted other companies’ attempts to build their own digital stores to sell music directly to the iPod. This kept things simple for the customers buying songs from iTunes at 99 cents a pop and arguably helped make the iPod a hit. It also ensured that Apple collected about 30% of sales. The 30% “tax” became the norm in the iPhone era—not only for music, but also for any piece of software sold through the App Store. In Apple’s view, this commission was more than reasonable given the costs of running the vast marketplace. And Brainerd says 30% is a pittance compared with the cuts that physical retailers took on his packaged software back in the day.

With this virtual storefront, Jobs was able to make more of Apple’s guidelines mandatory. Starting in 2008, software creators had to submit every mobile app and update to Apple’s review team before they could offer it to iPhone users, a process Apple saw as key to maintaining the device’s quality and security. Large groups of employees sitting at iMacs were each expected to assess 30 to 100 apps a day, rejecting software that was crappy, scammy, obscene or otherwise objectionable. If they screwed up and approved something Jobs felt they shouldn’t, the CEO himself would scold the review team, according to its then-head, Phillip Shoemaker. Four former app reviewers who worked for Apple during the 2010s say its regulations seemed arbitrarily enforced and bent to suit its financial interests. Apple says that reviewers base decisions on Apple’s guidelines, not subjectivity, and that the App Store has dramatically lowered the barriers for developers to reach consumers and earn money.

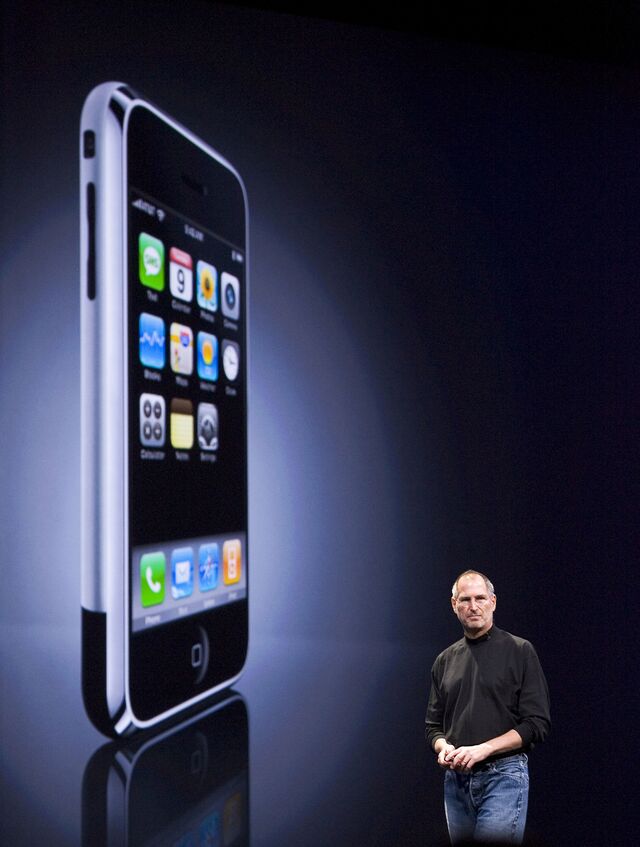

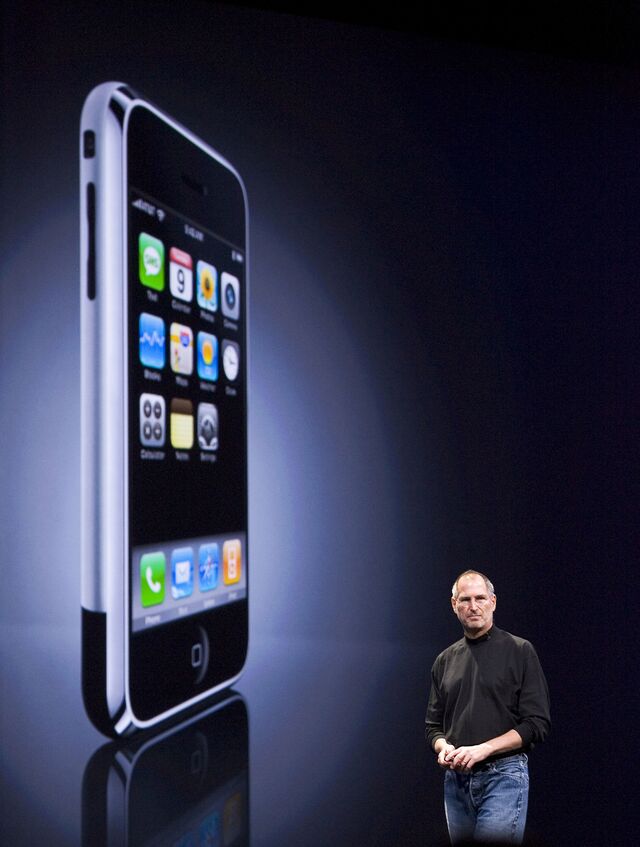

Jobs at Apple’s 2007 Worldwide Developers Conference in San Francisco. Photographer: Kim Kulish/Corbis/Getty Images

As Apple’s lists of rules grew longer, training for new reviewers sometimes stretched to two months or more. They became oddly precise in certain ways (no more “fart, burp, flashlight and Kama Sutra apps,” the company ordered at one point, citing a glut) and vague in others (it frowned on apps that were “complex or less than very good”). Apple also barred novel ways to add in-app purchases or subscriptions that would have allowed developers to circumvent the 30% fee. Rejection emails to developers tended to be opaque, with scant information on how to correct software issues. Apple says that its review team fields more than 1,000 calls per week from developers to help them resolve compliance issues and that there’s an appeals process for those who feel they were unfairly rejected.

Jobs’ exacting standards and his penchant for showmanship—embodied by his ironic use of the phrase “one more thing” to tease the biggest news at launch events—led to results. By the time he died in 2011, the App Store was a massive economy unto itself. It listed more than 500,000 apps for the iPhone and iPad. That year, Apple sold 72 million iPhones and 32 million iPads, and its market value rose to about $400 billion, almost double that of Microsoft Corp. If you’re under 40, it’s tough to appreciate what a dizzying reversal that was. For a generation, Apple computers had been the underdog, the niche province of kids, graphic designers and Bill Gates haters. Five years before Jobs’ death, on the eve of the iPhone’s announcement, Microsoft was still worth four Apples. Now the underdog was king.

Jobs’ successor was chosen to lock in those gains. Tim Cook wasn’t a design guru, and he wasn’t seen as having much interest in the creative side of the business. He apparently hadn’t shared Jobs’ disdain for the beige sameness of the average PC, either. Cook was a process guy and a cutter of costs. He’d been the one in charge of Apple’s hardware supply chain, a role he’d trained for by doing the same at Compaq and, before that, at IBM, the computing superpower that Apple implicitly framed as Big Brother in its “1984” ad.

To Jobs and his lieutenants, Cook got results somewhere between genius and miracle worker. He slashed warehouse inventory from a month’s worth of stock to a day’s worth, eliminating the costly risks of overproduction. He transformed Apple’s supply chain into a built-to-order powerhouse that rivaled Dell, then the gold standard of efficiency. He negotiated with the Taiwan-based manufacturer Foxconn to assemble the company’s devices in China for far less money than they would have cost if they’d been made by Apple workers elsewhere.

All these things worked out for Apple, allowing it to manufacture high-end phones cheaply while it effectively swallowed the majority of global smartphone-industry profits. The company’s suppliers, on the other hand, experienced something akin to the “Walmart effect”—the term coined to describe the dislocation created by dumping an enormous amount of business on a small company or community, sometimes with disastrous results. Foxconn employees, most of them young migrants, decried exceedingly low wages and long hours in what they and human-rights advocates described as labor camps where workers slept 10 to a room. During the first half of 2010, at least 10 Foxconn workers took their own life. “I feel empty inside,” a worker told Bloomberg News at the time. “I have no future.”

Foxconn raised salaries, created a hotline and installed suicide prevention nets, and Apple proclaimed the crisis resolved. In the years that followed, though, criticism from labor activists became a regular occurrence.5 Apple’s defenders argued that the complaints about Foxconn may have said less about Apple than about life in China for poor workers. On the other hand, Apple wasn’t always so obsessed with paying the lowest possible wages. The original Mac was assembled in Fremont, California.

Foxconn and its shareholders have found the Apple partnership tremendously profitable,6 though less important suppliers have griped about tactics they consider indifferent at best and predatory at worst. The most infamous of these was GT Advanced Technologies Inc. In 2013 it signed a deal with Apple to open a factory in Mesa, Arizona, to manufacture sapphire as part of an effort to make iPhone screens ultradurable. Within a year, the company was broke. In a bankruptcy declaration, a GT Advanced exec blamed Apple for a “classic bait and switch strategy” and dictatorial pricing that left it bearing all the risk, allegedly once demanding that the team put on their “big boy pants and accept the agreement.” The sapphire screens never came, and Apple, which disputed GT Advanced’s characterization and blamed the company for mismanagement, moved on. (GT Advanced later settled, without admitting wrongdoing, an SEC lawsuit that charged it with misleading investors. Apple settled a class action brought by GT investors while denying wrongdoing.)

In the decade that followed, a pattern emerged. Apple would sign a long-term deal with the supplier of a key component while working, in secret, to design an in-house replacement that would eventually render that supplier irrelevant. In 2017, for instance, the company told Imagination Technologies Ltd., which provided designs for iPhone graphics processors, that it was now building its own version of the chip, known as a graphics processing unit, or GPU. Imagination claimed the substituted chip infringed on its patents and amounted to theft. Apple eventually agreed to a new license deal, but by the time that happened, Imagination’s share price had collapsed and it had been sold to a China-backed private equity firm.

Three years later, Apple revealed it was winding down a long-term partnership with Intel Corp., choosing instead to use what it called “Apple silicon.” These chips were designed in-house and manufactured by Intel’s rival, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. The decision was understandable, and other big tech companies were taking similar steps. Intel had repeatedly delayed its next-generation chip and fallen behind TSMC. But Apple’s move coincided with a tailspin from which Intel has yet to fully recover.

This chain of events had geopolitical implications. Intel is the last American semiconductor company that makes its own state-of-the-art chips rather than outsourcing production to factories in Taiwan or South Korea. So Apple wasn’t simply imposing its supply chain methods on its partners. It was, to some degree, imposing its model on the US semiconductor industry, a key component of America’s economy and its national security.

In August 2020, Epic Games Inc., the studio behind the megahit Fortnite, introduced the world to a new character: the Tart Tycoon.7 He wore a slick suit and a scornful expression and had a head shaped like a Granny Smith. That the avatar was an obvious stand-in for Cook might have gone unnoticed, if not for the way Epic chose to introduce him: a shot-for-shot parody of Apple’s famous Super Bowl ad.

In the parody, which Epic posted on social media, the Tart Tycoon appears on a telescreen similar to the one imagined by Ridley Scott. “For years they have given us their songs, their labor, their dreams,” he thunders. “In exchange we have taken our tribute, our profits, our control.” Instead of a hammer, a Fortnite character runs in and destroys the screen using a rainbow-colored pickax in the shape of a unicorn. “Epic has defied the App Store Monopoly,” the text crawl reads, inviting gamers to “join the fight to stop 2020 from becoming 1984.”

Like many of Apple’s loudest critics, Epic CEO Tim Sweeney had been a fan of the company since childhood, and was also one of the original iMac developers that Jobs touted in 1998. But in recent years, Sweeney had been pressing Cook and other executives to allow software companies to open their own app stores on the iPhone, which would let Epic get around Apple’s content restrictions and high fees.

This suggestion went against the App Store’s official terms, but it wasn’t totally out of the question. Apple already had a secret deal with Amazon.com Inc. to halve its sales commission to 15% in exchange for introducing Prime Video on Apple TV, and it had privately warned Netflix Inc. that it would kill a similar arrangement unless the streaming giant stopped testing the removal of in-app subscription purchases intended to avoid Apple’s fees entirely.8 Apple had also allowed Tencent Holdings Ltd. and its 900 million-user messaging app, WeChat, to create internal “mini programs”9 that could order food or call a taxi, fudging its own rules. Apple says that it doesn’t play favorites and that rules related to premium video streaming and mini programs were ultimately enforced uniformly. In late 2020, Apple announced it would allow any developer with less than $1 million in revenue to pay a 15% commission instead of the standard 30%.

Epic didn’t have WeChat-level clout, but Tencent was an investor in Epic and Fortnite was a blockbuster. So, before taking his concerns public, Sweeney attempted to negotiate. In June he sent an email to Cook and several deputies requesting that Apple allow competing app stores from Epic and other developers to make software distribution as open as it is on PCs. After Apple objected, he sent another email, at 2:08 a.m. Cupertino time on Aug. 13, declaring that Epic would “no longer adhere to Apple’s payment processing restrictions” and instead launch its own commerce system within Fortnite. In other words, Sweeney unilaterally decided to stop paying the Apple tax. Apple responded by booting Fortnite from the App Store. Within hours, Epic posted “Nineteen Eighty-Fortnite.” It also filed a 65-page lawsuit.

A federal judge ultimately ruled that Epic breached its contract with Apple and that the App Store was lawful as is, provided Apple made one important adjustment. Epic and other developers should be allowed to link to their own payment systems on the web and thus get around some of Apple’s fees. But when Apple later added this functionality, it also introduced new rules and fees that made the external purchase option pointless. Any developer adopting this new system would have to agree to share its website transaction records with Apple, submit to audits and pay a 27% commission on any payments that happened outside the iPhone. The number seemed significant. Credit card processing fees generally run about 3%, which meant Apple had effectively replaced its 30% tax with one that added up to the same number, but with a lot more paperwork. Epic cried foul, arguing in a legal filing that “Apple’s so-called compliance” was “a sham.” Both companies are back in court.

A member of Epic Games’ legal team enters federal court in 2021. Photographer: Ethan Swope/Getty Images

Sweeney (left) exiting the courthouse in Oakland, California. Photographer: David Paul Morris/Bloomberg

Nevertheless, Epic’s lawsuit symbolized a turning point in Apple’s relationships not only with software makers but also with the partners on which its entire ecosystem depends. A few, such as Spotify Technology SA, were furious enough about the built-in advantages of rival Apple services that they became vocal critics of what they alleged were anticompetitive practices. At the same time, in many other corners of Apple’s empire, powerful partners were beginning to grumble behind the scenes. Apple says that the vast majority of its partners have thrived as a result of working with the company and that its high standards are intended to deliver the best products for its customers.

Apple Card. Source: Apple

One disgruntled partner was Goldman Sachs Group Inc., which had joined with Apple two years prior to introduce the Apple Card, a titanium credit card that promised to disrupt consumer finance. According to a former senior manager at the investment firm, the Goldman team found their counterparts at Apple exceedingly arrogant in haggling about everything from legal compliance to marketing. When the card was unveiled, it featured a slogan about how it was “created by Apple, not a bank,” upsetting Goldman execs. “People were like, ‘What do you mean you made this thing by yourself? ’Cause you don’t know how to make a f—ing loan or do regulations,’ ” the manager recalls. “It felt like we were just a vendor, and Goldman Sachs is not used to being treated like a vendor.” A Goldman spokesperson declined to comment.

A similar dynamic was playing out in Detroit. Apple CarPlay, the software used to show iPhone apps on vehicles’ screens, was initially regarded as a nice amenity for drivers. Eventually, however, some automakers began to worry that Apple was trying to wire itself irrevocably into all their cars. In 2022, Apple announced that CarPlay was expanding into the speedometer, climate controls, oil gauges and other areas. People familiar with General Motors Co.’s thinking say Apple rarely listened to product feedback, treating GM’s cars like a distribution hub for its software. Alan Wexler, GM’s senior vice president for strategy and innovation, told Bloomberg Businessweek earlier this year that the next-generation CarPlay risked turning its vehicles into “an iPhone you’re driving.” Apple says CarPlay is optional and free for automakers to integrate.

Ted Lasso, Season 1. Source: Apple TV+

By this point, Apple’s cultural influence reached well beyond tech and into Hollywood. Apple TV+, the premium streaming service, had produced one bona fide phenomenon, the fish-out-of-water sitcom Ted Lasso. Throughout the rest of the division, though, artist types began to lodge complaints that would have sounded eerily similar to any iPhone developer, describing a company willing to massively overspend or shutter projects for reasons that seemed arbitrary, unclear or just plain weird. A producer of one of the company’s shows says the entire effort has felt empty and self-interested, like “an in-house branding exercise for the richest company in the world that only made sense in a zero-interest-rate environment.”

Apple killed a sitcom co-created by Cord Jefferson, now an Academy Award-winning screenwriter,10 because Cook apparently held a grudge against the defunct blog Gawker, a former employer of Jefferson’s and the inspiration for the show. It cut ties with comedian Jon Stewart because of creative differences over how to cover topics that touched on Apple’s business. This spring, Stewart, now back on The Daily Show, interviewed Federal Trade Commission Chair Lina Khan, who’s been leading the Biden administration’s antitrust crackdown.

In a previous segment, Stewart had performed a monologue gently mocking tech executives for making outlandish claims about artificial intelligence. To Khan, he said his bosses at Apple, which has been aggressively trying to add AI features to its devices, had rejected the idea outright. “Why are they so afraid to even have these conversations out in the public sphere?” Stewart asked. Khan suggested Apple’s market dominance was the problem. “It just shows one of the dangers of what happens when you concentrate so much power and so much decision-making in a small number of companies,” she said.

Stewart noted that he’d tried to interview Khan while he was still at Apple but had been shot down on that idea, too. “Apple asked us not to do it,” he said. Then the comedian deadpanned, “Having nothing to do with what you do for a living.”

Eleven days before Khan appeared on The Daily Show, her counterparts at the DOJ filed a lawsuit that sought to dramatically constrain Apple’s power. According to people involved in the case, prosecutors had been investigating Apple since 2019, interviewing the company’s partners—including executives from GM and Goldman—and amassing a trove of internal documents. They’d also attended every day of the Epic trial, listening for potential evidence for their own investigation and for insight into possible legal strategies.

Part of what had weakened Epic’s case, as the federal prosecutors understood it, was that Google’s app store has comparable platform fees and rules but many more people use it. That is to say, it wasn’t clear Apple even had a monopoly on the app store market. (Epic had sued Google, too, and a jury ruled in its favor in December 2023. Google is appealing the verdict.)

In crafting its case against Apple, the DOJ widened the aperture, focusing on the ways Apple’s controls over its ecosystem have enabled it to dominate what the complaint described as the “performance smartphone market,” where the government claimed its share of US revenue is more than 70%. There’s no universally accepted “performance smartphone market,” as Apple countered in its response.11

Moreover, the lock-in effects that the Justice Department case targets just happen to be the very thing Apple consumers most love about its products—that they feel safe and dead simple to use. But the DOJ’s ultimate point was that Apple’s integrated hardware, software and App Store suppress competition by making it almost impossible to leave for rival equivalents. Simply migrating your life from an iPhone to an Android device is hard enough while keeping your personal data and purchased content. Never mind if you’ve paid for a gaggle of other expensive Apple devices and subscriptions, too.

The DOJ complaint, filed in March, also targeted the role Apple had played in allegedly hamstringing its competition to create that situation. For instance, Apple limits the ability of third-party smartwatches to stay continuously connected to the iPhone in certain situations, making them work slightly less slickly than an Apple Watch. In mobile messaging, non-Apple text messages are displayed in green bubbles, whereas those sent through its own hardware show up in blue, creating a social stigma for non-iPhone users. (A genre of memed TikTok videos begins with the prompt “He’s a 10, but he uses an Android phone. What’s his new rating?”12) The lawsuit will take years to litigate, but the DOJ’s successful case against Google shows how high the stakes are. The government is considering asking a judge to break up the search giant and could do the same to Apple if it prevails.

Even if the case is dismissed, the lawsuit still might signal that Apple’s leadership is fading. Anticompetitive behavior, after all, is sometimes a symptom of a company that’s run out of ideas. “It’s not the Apple that once pushed the boundaries of technology and design,” Spotify CEO Daniel Ek wrote earlier this year. “This is a company resting, not breaking any new ground, and turning its back on the principles that once made it the shining example of innovation.”

That charge is hardly new. For almost the entirety of Cook’s tenure as CEO, critics have suggested Apple would never release a product that could live up to the success of the iPhone. There are counterarguments: The Apple Watch and AirPods have both sold well enough to define new categories. The company’s laptops and tablets are consistently ranked as the best. But its portfolio has also succeeded in large part because many of these offerings are essentially iPhone extensions, the default options if you already live your digital life in Apple’s garden. Their success may illustrate the Justice Department’s point rather than refute it.

Earlier this year, Apple scrapped an electric-vehicle project after spending $10 billion over a decade. Its Vision Pro headset has yet to catch on with developers, perhaps because of the company’s strained relationships with partners, or with consumers, who’ve mostly ignored it because it costs $3,500. For now, the headset has two uses: as a very expensive personal movie theater and a hell of a metaphor, incorporating Apple’s meticulous control into a wearer’s every moment. It is, in that sense, the inverse of the “1984” commercial. Rather than empowering people to smash the telescreen, Apple seeks to envelop them inside of one.

Will that matter? In the short run, no. For all the regulatory pressure and public criticism, Apple’s share price hasn’t suffered. It surged to an all-time high on July 16. Apple had recently announced new AI tools and an enhanced virtual assistant coming to the iPhone. The bot’s features will be superior to those of the old Siri but more modest than those of ChatGPT. If the new Siri can’t answer a question, it will simply offer a link to OpenAI’s service. It’s a safe, incremental fix, “one more thing” in the most mundane sense.

But in the long run, it’s hard not to see a company that’s lost some of the moral authority it worked so hard to cultivate when it created the Mac. If Apple treated its early partners the way it treats its current ones, it’s possible Apple wouldn’t still exist. The first killer app arguably ever written, a spreadsheet program for the Apple II called VisiCalc, transformed the pre-Mac company from a hobbyist distraction to a PC pioneer. Co-creator Bob Frankston says if Jobs had tried to impose anything like today’s rules on the VisiCalc team, his “technical response” would have been a “middle finger raised to the sky.” Another legendary computer scientist, Alan Kay, whose work at Xerox PARC inspired the groundbreaking point-and-click interface on the original Mac, complains that the post-iMac version of the company has drifted from Jobs’ original idealistic goals. “He chose ‘conveniences for mass consumers’ versus his earlier goals of ‘wheels for the mind,’ ”13 Kay says. “The iPhone and iPad physically resemble some of my early ideas, but their use has been almost opposite to how I thought they should be used.”

Apple itself is aware of this shift in perception, even if it seems unsure how to navigate it. This past spring the company aired and then quickly stopped promoting an ad,14 “Crush,” that seemed to perfectly capture the sense among critics that Apple’s power had become destructive. “Crush” opens with a mammoth hydraulic press bearing down on a pyramid of real-life creative tools. Under the press are an upright piano, a guitar and a trumpet; an easel with bottles of paint; a clay bust; a chess set; a vinyl record player; camera lenses; and a stack of notebooks. As Sonny & Cher’s All I Ever Need Is You plays in the background, the press lowers, unstoppably and undeniably, squeezing everything inside into colorful dust. Then the press is raised to reveal Apple’s new iPad. It’s thinner than the last model. —With Leah Nylen