Jobs

How Bad Was the July Jobs Report?

After arguing for over a year that it was time for the Fed to start lowering rates to avoid an economic slowdown, I feel a need to give a bit of pushback against all the folks who are now rushing to agree with me. To be clear, I absolutely think the Fed should lower rates, and the sooner the better (a between meetings reduction would be fine by me), but the talk of an economic collapse and impending recession are more than a bit over the top.

First, let’s catch a breath and look at the actual numbers. The unemployment rate for July was 4.3 percent (4.25 percent going to the next decimal). That is still low by historical standards, but it is up by nearly a percentage point from the 3.4 percent rate hit last April. More importantly, it is up from a rate 3.7 percent in January. An increase in the unemployment rate of 0.6 percentage points in six months is definitely cause for concern.

But there is reason to believe that weather may have played some role in this increase. While a note from BLS said that there did not find clear evidence of a weather effect from Hurricane Beryl in response rates, that doesn’t mean that the hurricane had no effect on the data. Most obviously, 461,000 people reported that they had a job but were unable to work due to the weather. That compares to 83,000 in June and 55,000 in July of 2023.

Another 1,089,000 reported they worked fewer hours than normal. That compares to 206,000 in June and 164,000 last July. In a similar vein, the number of people who reported being on temporary layoff increased by 249,000 in July, accounting for more than 70 percent of the reported rise in unemployment. This would support the view that the hurricane played a considerable role in the rise in unemployment in July.

It’s also worth noting that not everything in the household survey for July was not bad. Most importantly, the employment to population ratio (EPOP) for prime age workers (ages 25 to 54) actually rose 0.1 pp in the month to 80.9 percent, tying the peak for the recovery. We don’t usually see EPOPs for this group of workers rising in a recession.

The data from the establishment survey is also mixed rather than uniformly bad. The 114,000 jobs created for the month is low compared to what we have been seeing, but it’s not clear that it is much lower what we should be expecting. The last economic projections from the Congressional Budget Office before the pandemic showed job growth of just 250,000 a year from 2023 to 2025, as the retirement of the baby boomers was expected to sharply limit job growth.

Even the projections from June of this year show the economy adding just 1.8 million jobs, or 150,000 a month, between the second quarter of this year and the second quarter of 2025. The July figure is obviously somewhat below this number, but the 170,000 average for the last three months is comfortably above it.

These qualifications of the bad news in the July report should not be taken as questioning whether the labor market is weakening. It clearly is, and that is supported by a large amount of other data, such as the drop in the job opening, hiring, and quit rates in the JOLTS data. We also have private data sources such as Indeed and ADP that tell a similar story. And, we know that wage growth has slowed almost back to the pre-pandemic pace in the Average Hourly Earnings series, the Employment Cost Index, and the Indeed Wage Tracker.

A Weaker Labor Market Is Not a Recession

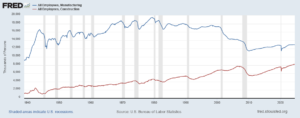

However, it is important to distinguish between saying we are seeing a weaker labor market and we are on the cusp of a recession. The economy is still creating jobs at a respectable pace, even if it may not be rapid enough to keep the unemployment rate from rising. It is especially worth noting that the two most cyclical sectors, construction and manufacturing, are still adding jobs, although very slowly in the latter case. In prior recessions, these sectors began losing jobs before the official start of the recession.

The two sectors together lost 110,000 jobs in the six months prior to the 1990 recession, 237,000 jobs in six months before the 2001 recession, and 360,000 jobs in the six months leading up to the Great Recession. In the last six months, these sectors have added 133,000 jobs. If we are on the edge of a recession, it clearly is going to look very different from prior recessions.

It is also worth noting that this is not just an issue of correlation. There is a logic whereby job loss in these sectors led to a recession. These sectors tend to pay more than the overall average, both at an hourly rate (this is less true today for manufacturing, as the wage premium has been seriously eroded) and also because these jobs have considerably longer average workweeks.

When there is substantial job loss in these sectors, it translates into less purchasing power in the economy, leading to the sort of cascading effect that gives us recessions. We are clearly not on this path at present.

We also can look at weekly filings for unemployment insurance. These always rise sharply before the start of a recession, as shown below. (I have not included the pandemic recession because it would wreck the scale of the graph.)

There has been a modest rise in the number of weekly claims since the lows hit in 2022, but the most recent four-week average of 238,000 is still low by historical levels and even below levels hit last summer. In short, it is hard to look at these data and see an economy on the brink of recession.

The Fed Should Still Lower

As Chair Powell has repeatedly noted, the Fed has a dual mandate for stable prices and full employment. It seems as though the Fed has maintained a single-minded focus on the price stability part of the mandate for the last year, even as inflation has slowed sharply and the labor market has weakened. At this point it is hard to justify a 5.25 percent federal funds rate.

Expectations of inflation are now slightly above 2.0 percent, which means that the real federal funds rate is over 3.0 percent. That is seriously contractionary. Through most of the period prior to the pandemic, the real rate was close to zero and often negative.

An excessively contractionary policy from the Fed may not push us into recession any time soon, but it could mean hundreds of thousands of people are being denied jobs due to a weak labor market. And millions of people who might otherwise leave jobs for better ones, or push for higher pay at their current job, are being denied this opportunity. And high mortgage rates continue to take a huge toll on the housing market.

We don’t have to start yelling that the sky is falling. None of the data supports that story. But the labor market is clearly weaker than it has to be, and the Fed can help to turn it around with an aggressive set of rate cuts in the second half of this year.

This first appeared on Dean Baker’s Beat the Press blog.