Travel

How Horror Movies Play on Our Travel Nightmares

We all have our vacation horror stories: canceled flights, bedbugs, food poisoning, several midwinter nights spent in a remote Irish hostel with a pair of horny German exhibitionists. Okay, perhaps that one is a little more personal. All of these experiences feed on how helpless we can feel while traveling, entirely at the mercy of conductors, cooks, and concierges, oftentime struggling to speak languages we don’t entirely grasp. You leave your home, and give yourself over to the new, the unfamiliar—and, if a certain genre of movie is to be believed, to the terrifying.

This dual experience—of discovery and horror—is at the heart of this summer’s Speak No Evil. Adapted by director James Watkins from a 2022 Danish film of the same name, it begins in sunny Italy, where the American couple Ben and Louise Dalton (Scoot McNairy and Mackenzie Davis) have traveled with their daughter Iris (Alix West Lefler). Awkward and shy, the couple find themselves taken in by Paddy and Ciara, a charismatic, daring, sexy British pair played by James McAvoy and Aisling Franciosi, who are vacationing with their mute son Ant. The parents get along, the kids get along, and when the Daltons have to return to their lonely London apartment, the come down is palpable.

Which explains why, when they receive an invitation to visit Paddy, Ciara, and Ant at their farm in the rural west country, the Daltons accept. Yes, it’s in the middle of nowhere, sure they have no cell service, and okay, Paddy immediately starts to push social boundaries, skulking around the house, eavesdropping on their private conversations, making off-color jokes, and pressuring the vegetarian Louise to take a bite of their prize roast goose. But isn’t that why they’ve gone on a trip in the first place? We travel to experience these exact breaches in normalcy, the changes in diet and manners and expectations that come with arriving in a place which is new to us. Even as the discomfort ramps up, the liberal, polite, Daltons do their best to not to judge, and for a time they even allow themselves to enjoy the provocations, drinking too much, shooting guns, and confessing to strangers what they would not tell their own friends—a choice which their hosts are willing and ready to exploit.

The specifics of Paddy and Ciaras diabolical plan take a while to come into focus. But Watkins (and his Danish predecessors) mine plenty of horror out of the social transgressions and alienating experiences familiar to anyone who has traveled beyond their domestic comfort zone. In opening ourselves up to new experiences, the narrative goes, we risk allowing danger to slip by in a form we do not recognize. By the time we do, it’s already too late.

This is the basic premise of the genre we might call Travel Horror. A group of people, often American, almost always young, head off for excitement in parts unknown. Their destination might be a cave, a jungle, a resort, a city—or, in the case of Speak No Evil, a creaky old farmhouse a short drive from the English coast. They encounter wonders, have new experiences, maybe even indulge in the sort of delights, carnal or otherwise, which they would never dare in their everyday lives. Yet this pleasure is all set-up for the second-act turn, when the seeming idyll is revealed as distraction, a hunting blind thrown up around extremes of terror and pain our characters could never have imagined.

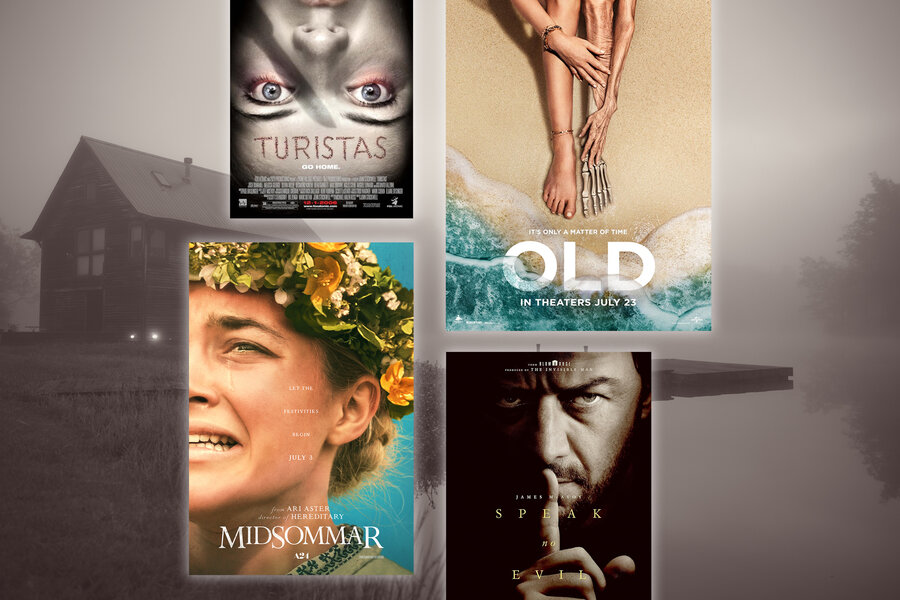

Hostel and imitators like Turistas set the mold: foreign settings, duplicitous locals, drinks and drugs and horrible violence.

These films allow viewers to indulge alongside the characters, serving up beautiful vistas and prurient sights and the sense that, away from our homes, the normal rules do not apply—in both directions. In Eli Roth’s Hostel, a group of shithead backpackers hop between nightclubs and brothels. Their hedonistic existence comes to a screeching halt when they arrive at a Slovakian hostel which is in fact a front for a sadistic torture ring. This group, the Elite Hunting Club, serves up faceless backpackers like our heroes to wealthy Europeans, who pay great sums to torture and maim total strangers. Roth presents eastern Europe (with the Czech Republic subbing in for Slovakia) as a lawless zone where foreigners indulge and are punished, and only the viewer emerges whole.

Hostel and imitators like Turistas set the mold: foreign settings, duplicitous locals, drinks and drugs and horrible violence. The nature of the threat might change—The Ritual’s forest monster, Wolf Creek’s sadistic serial killer, the pharmaceutical resort and the beach that makes you Old—but it is usually rooted in a tourist’s incomplete perception of the place they’re visiting. What seems beautiful is revealed to be ugly, an initial sense of calm gives way to panic, and hospitality is only too late recognized as a cover for brutality. Sometimes that horror remains foreign; in others, like the masterful prologue of The Empty Man, it infects the visitor, and they carry it home. But the threat is always out there; had they simply stayed home, there would be no story to tell.

Needless to say, these stories about a fear of the foreign, of true horror ready to strike in faraway countries, are pretty xenophobic, and often outright racist. It makes sense that so many of them arose with the torture porn genre in the early 2000s, when a post-9/11 America took upon itself the mantle of world-crusader. Whether European businessmen or Brazilian organ-theft gangs or the Albanian sex traffickers from Taken, innocent Americans are forever under threat. 2014’s Indigenous takes place in the Darien Gap, a mountainous stretch of Panama through which hundreds of thousands of migrants are forced to trek. When the film was made, this number was much lower. Yet there is something wilfully blind about a movie set in a real, deadly place, whose victims are not desperate migrants, but dumb white tourists menaced by (sigh) the chupacabra. There are exceptions, like Ari Aster’s Midsommar, which mocks and mutilates its backpacker protagonists before rewarding Florence Pugh’s Dani for her willingness to assimilate. But even here, the strange Scandinavian pagan cult still crowns an American, a fairy tale ending made no more complex for all its perversity.

In this way, Travel Horror isn’t so far off from the wish fulfillment fantasies offered by movies like Eat, Pray, Love and Under the Tuscan Sun. These stories center around well-to-do types who, having grown dissatisfied with their comfortable lives, set out into the world in search of deeper meaning. On the course of their journey they meet wise locals, discover new traditions, fall madly in love with new places and people, and emerge self-actualized, richer for their experiences (and still, it’s implied, just plain rich), better versed in the wisdom of the world.

Yet this is not an exchange: the traveler does not give anything of his or herself to the places they have visited, and is not asked to come to any uncomfortable conclusions vis-a-vis the people around them. While ostensibly xeno-philic, this engagement with foreign countries and cultures is no more complex. Here, the entire vast swathe of the human and natural world is reduced to a stage on which the wealthy westerner can act out their journey of self-discovery, flattening the great variety of the world’s cultures into a set of readily-graspable anecdotes and mantras.

These are different kinds of horror stories, positing a foreign other which we contact to change ourselves, for good or ill, on a terrain where we discover things about ourselves: our capacity for love, for pain, for the heightsand depths of human nature. Strange as it sounds, these genres validate the visitor, transforming them into the main character, no matter how little they understand the place they’re visiting. The only difference between massage and dissection is how deep they get into the tissue. Without the tourist, it’s implied, there would be no world, no culture, no life, a self-centered, myopic view shared, it’s safe to say, by many travelers.

Speak No Evil can’t help arriving in a similar place. As the evil plan comes to light, the Daltons act almost flattered by the scheming of their hosts—all that villainy, for us? The entire ecosystem of this little corner of rural England seems to run on the ill-gotten gains filched from visitors, a metropolitan’s bug-eyed nightmare of the hinterlands as full of parasites sucking the city-dwellers dry. There’s no choice but to burn it all down and return back home—a different kind of travel horror story, if not exactly the one the film means to tell.

Robert Rubsam is a freelance writer and critic. His work has been published in the New York Times Magazine, the Washington Post, the Baffler, the Atlantic, the Paris Review, and Vulture, among other places.