World

How Lore Segal Saw the World in a Nutshell

Lore Segal, who died on Monday, spent the last four months of her life looking out the window. Her world had been shrinking for some time, as a hip replacement, a pacemaker, deteriorating vision, and other encroachments of old age had made it difficult to leave her New York City apartment, even with the aid of the walker she referred to as “my chariot.” But now, after a minor heart attack in June, she was confined to a hospital bed at home. There, she could study the rooftops and antique water tanks of the Upper West Side—a parochial vision for some, but not for the Viennese-born Segal, who once described herself as “naturalized not in North America so much as in Manhattan.”

Of course, she was an old hand at seeing the universe in a nutshell. It was one of her great virtues as both a writer and a person, and her affinity for tiny, telling details had drawn me to her work long before I became her friend. I also loved her freshness of perception. In Segal’s 1985 novel, Her First American, Ilka Weissnix, newly arrived in this country, disembarks from a train in small-town Nevada and has what must be one of the very few epiphanies ever prompted by a glue factory. “The low building was made of a rosy, luminescent brick,” Segal writes, “and quivered in the blue haze of the oncoming night—it levitated. The classic windows and square white letters, saying AMERICAN GLUE INC., moved Ilka with a sense of beauty so out of proportion to the object, Ilka recognized euphoria.”

To some extent, this euphoria must have stemmed from Segal’s own history as an immigrant. She left Vienna on the Kindertransport in 1938, then lived in Britain and Santo Domingo before making landfall in the United States in 1951. Her books are full of people who have been dislodged from one place and set down in another. The challenges of such displacement are obvious. But it can be a gift for a writer, dropped into a glittering environment whose every detail is, to use Segal’s favorite word, interesting.

She also possessed extraordinary empathy. Segal was quite specific about what this meant, and resisted the idea of being seen as a victim, even when it came to her narrow escape from the Third Reich’s killing machine. “Sympathy pities another person’s experience,” she once wrote, “whereas empathy experiences that experience.” It was getting inside other people that counted, even if our grasp of another human soul was always partial.

Her empathetic impulse accounted for a hilarious comment she once made to me about her television-watching habits: “I don’t like to watch shows where people feel awkward.” Because this is the modus operandi of almost every post-Seinfeld TV show, it must have really cut down Segal’s viewing options. I think what bothered her were scenarios specifically engineered to bring out our helplessness in social or existential situations. She found it hard to hate other people and couldn’t even bring herself to dislike the water bug that lived in her kitchen.

I’m not suggesting that Segal was some sort of Pollyanna. She was well aware of our capacity for cruelty and destruction—it had, after all, been shoved in her face when she was very young. But her fascination with human behavior on the individual level seemed to insulate her from received thinking on almost any topic. “Contradiction was her instinct, her autobiography, her politics,” Segal wrote of her doppelgänger, Ilka, who reappeared in Shakespeare’s Kitchen more than 20 years after the publication of Her First American. “Mention a fact and Ilka’s mind kicked into action to round up the facts that disproved it. Express an opinion and Ilka’s blood was up to voice an opposite idea.” Everything had to be freshly examined; everything had to pass the litmus test that is constantly being staged in a writer’s brain.

Segal also brought this approach to ideological truths, few of which made the grade. It’s fascinating to me that a writer so allergic to ideology managed to produce one of the great Holocaust narratives and one of the great American novels about race—projects that might now be hobbled by questions of authenticity and appropriation. For Segal, the glut of information, and the ethical exhaustion that resulted, turned contemporary existence into a minefield, and politics was no way out. Decency was, but that took enormous work and concentration.

“To be good, sane, happy is simple only if you subscribe to the Eden theory of original goodness, original sanity, and original happiness, which humankind subverted into a fascinating rottenness,” she wrote in an essay. “Observation would suggest that we come by our rottenness aboriginally and that rightness, like any other accomplishment, is something achieved.” In all of her books, in every word she wrote, Segal struggled for that very rightness. I would say she achieved it too, with amazing frequency.

I cannot think about Lore Segal’s work without thinking about my friendship with her. For years and years, I read her books and admired her from a distance. It was only in 2009 that I finally met Lore, as I will now call her. Her publisher was reissuing Lucinella, a madcap 1976 novella that somehow mingles the literary life with Greek mythology: Zeus turns up at Yaddo, the prestigious artists’ colony, in a notably priapic mood. I was asked to interview her at a bookshop, and we hit it off at once.

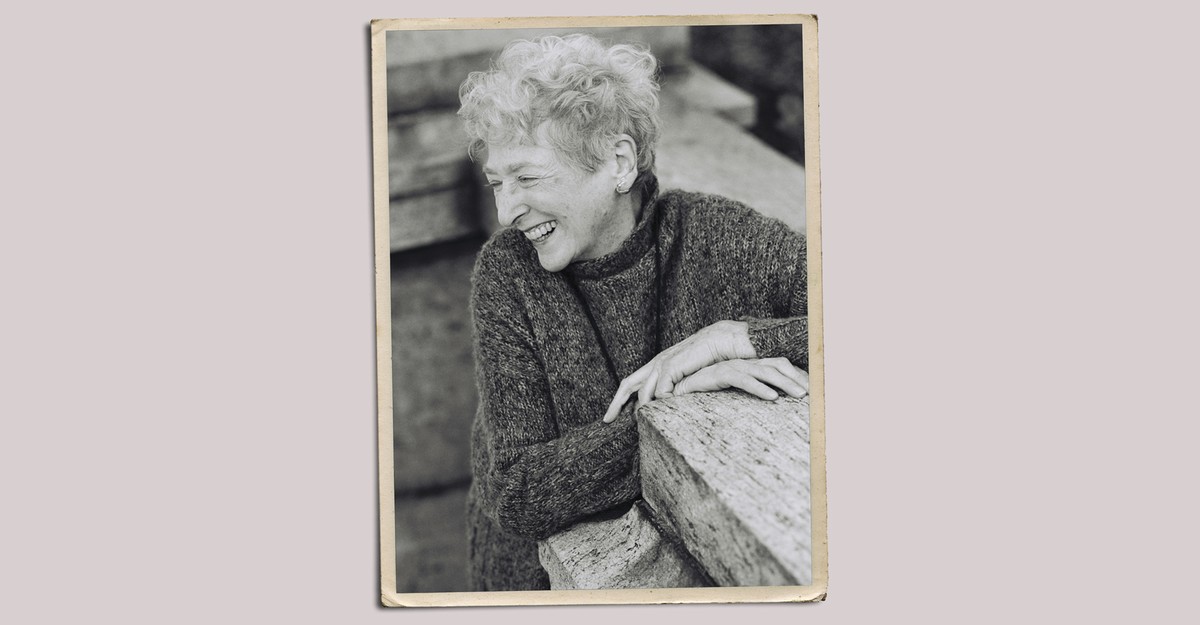

This small, witty, white-haired person, whose voice still bore the inflection of her Viennese childhood, was a joy to be around. She laughed a lot, and made you laugh. Her marvelous capacity to pay attention made you feel larger-hearted and a little more intelligent—it was as if you were borrowing those qualities from her. In her apartment, with its grand piano and Maurice Sendak drawings and carefully arranged collections of nutcrackers and fin de siècle scissors, we spent many hours visiting, talking, joking, complaining. We bemoaned the slowness and blindness and intransigence of editors (even during the years when I was an editor). We drank the dry white wine I’d buy at the liquor store three blocks away, and Lore always pronounced the same verdict after her first sip: “This is good.”

In time, she began sending me early drafts of the stories that would eventually make up most of her 2023 collection, Ladies’ Lunch. As her vision worsened, the fonts grew larger—by the end, I would be reading something in 48-point Calibri, with just a few words on each page. I was flattered, of course, to function as a first reader for one of my idols. I was touched as well to discover that she was still beset with doubts about her work. “Wouldn’t you think that age might confer the certainty that one knows what one is doing?” she lamented in an email a couple of years ago. “It does not. It deprives.”

We saw each other, too, at meetings of our book group, which Lore had invited me to join in 2010. In more recent years, we always met at Lore’s, because it had become harder and harder for her to bundle herself and her walker into a taxi. Only a few weeks before she died, the group met one last time, at her insistence. She had chosen a beloved favorite, Henry James’s The Ambassadors, and was not going to be cheated out of the conversation.

We sat around her hospital bed, with her oxygen machine giving off its periodic sighs in the background. Lore, peering once more into the microcosm of James’s novel and finding the whole world within it, asked the kind of questions she always asked.

“Are the characters in this novel exceptional people?” she wanted to know.

“Of course not,” replied another member of the group. “They’re absolutely typical people of the period, well-heeled Americans without an original thought in their heads.”

This did not satisfy Lore. She felt that Lambert Strether, sent off to the fleshpots of Paris to retrieve his fiancée’s errant son, had been loaned some of James’s wisdom and perceptive powers (exactly as I always thought I was borrowing Lore’s). “Live all you can,” Strether advises, with very un-Jamesian bluntness. And here was Lore, living all she could, sometimes resting her head on the pillow between one pithy observation and the next. It was the capacity to feel, she argued, that had been awakened in the novel’s protagonist. Empathy, rather than analysis, was Lore’s true currency to the very end.

I visited her just a few more times. She was fading; the multicolored array of pills and eye drops on the table grew bigger and more forbidding; the oxygen machine seemed louder with just the two of us in the room.

“I hope I’ll see you again,” I said, the last time I left. These are the sort of words usually uttered at the beginning of a friendship, not at the conclusion. “But whatever happens, I’ll be thinking of you.”

Out the door I went, and boarded the elevator, in whose creaking interior I shed a few tears, and as I strolled up one of those Upper West Side streets mounded with the trash bags that Lore had so eloquently described (“the bloated, green, giant vinyl bags with their unexplained bellies and elbows”), I found myself asking: Why do we cry? How do we cope with loss? What, precisely, is sadness? These were the questions that Lore would ask—the questions she had been asking her entire career. Her books constitute a kind of answer, at least a provisional one. I will be reading them for the rest of my life and, exactly as I promised Lore on my way out the door, thinking of her.