World

How should a world No 1 be? Iga Swiatek and Naomi Osaka have an idea

Long before Iga Swiatek was Iga Swiatek, the intermittently outspoken tennis wrecking machine and world No 1, and back when Naomi Osaka was just starting to become Naomi Osaka, a barrier-breaking icon of sports and culture, the teenager and the twentysomething had a frank chat about Swiatek’s future.

Swiatek, 18 at the time and still a high school student saddled in the bottom half of the top 100, was doing homework in player lounges still. She told Osaka she was thinking of going to college. She wasn’t sure pro tennis was the right path for her, at least not yet.

Osaka, who had hit and played against Swiatek, told her she was wrong. She said that she was a “really good” tennis player, better than most. Go to college, if you want, she said, but make no mistake, if you want to be a professional tennis player — it’s right there for you.

And how. Osaka has joked that it might have been the worst advice she ever gave someone, at least as far as her career was concerned. Not long after that chat, Swiatek won her first French Open, the first player from Poland to become a Grand Slam singles champion. A year and a half after that, she became the world No 1 for the first time, and a folk hero in her country.

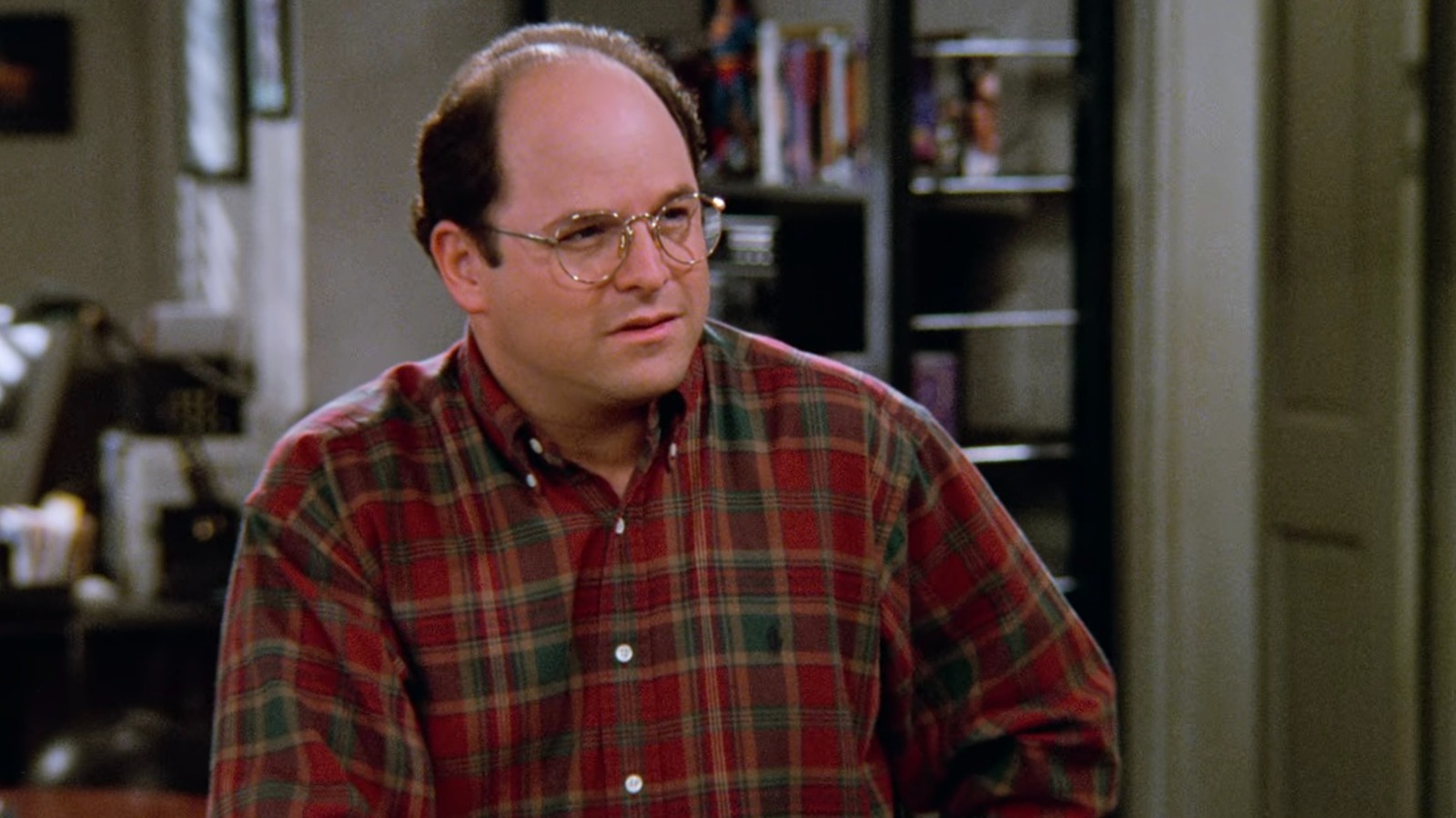

Swiatek and Osaka delivered a classic on Philippe-Chatrier (Dan Istitene/Getty Images)

They have been the friendliest of rivals ever since, so similar but so different. One is a child of Eastern Europe’s post-Cold War era, the other a half-Japanese, half-Haitian woman raised largely in America.

Both have wrestled with the idea that being the world’s top tennis player is more than just a sports calibration. It brings fame, wealth and privileges, but also obligations and responsibilities that make anyone who holds the title search for the right way to exist as the world No 1. As tennis enters a transitional moment, emerging from two decades of cross-cultural gold dust largely sprinkled by three men and two sisters, the question of not just which player dominates camera lenses and microphones, but how she should do it is coming into view once more. The answers, like the game itself, are never easy.

Through the afternoon and early evening of Wednesday on Court Philippe-Chatrier, Swiatek and Osaka dueled for the kind of three-hour, roller-coaster of a battle between four-time Grand Slam champions that begged for it to be a final rather than a second-round contest. Osaka started edgy, then found her groove and took over, commanding the court for most of the final two and a half sets. She came within a point of beating Swiatek on the court that she is making her living room in the same way her idol Rafael Nadal did, only to fall victim to a tight arm in the crucial moments, dropping the final five games as Swiatek prevailed 7-6(1), 1-6, 7-5. It raised hopes that Osaka’s comeback from pregnancy, childbirth and maternity leave is just starting to get rolling, that these two will be doing what they did Wednesday a whole lot more down the road.

“There are moments that I could have stepped in a lot more, and I could have done better, but it’s all part of the process,” Osaka said philosophically, less than an hour after the match. She’d had a quick cry once she walked off the court, then thought better of life, knowing that she’d be holding her daughter back at her Paris landing spot before too long.

Swiatek said she was thrilled to be facing this version of Osaka once more, somewhat awed that it had happened just 10 months after Osaka had given birth.

“I have big respect for her coming back, because of the things that she struggled with” she said. “Another thing, she’s a mother.”

GO DEEPER

Naomi Osaka, The Comeback Interview: A tale of pregnancy, fear and a ballerina

Osaka had been on a different path by the time Swiatek ascended to the top of the game. Ambivalent about the demands of professional tennis, her fame, still growing into her existence as a lightning rod in the discussion of violence against people of color in America. Prone to waves of depression and anxiety, she wasn’t sure how tennis was going to fit into her life, or how to use her platform most effectively. She took one long break, and then another.

Osaka after victory over Victoria Azarenka in 2020 (Al Bello/Getty Images)

Osaka is outspoken on civil rights issues. In 2020, at the end of a summer of notorious police violence against Black Americans, she had brought the sport to a standstill in late August when she announced she would not play her semi-final of the Western & Southern Open. Following the police shooting of Jacob Blake that produced a broad work stoppage of sports in America, she explained her decision on social media.

“I don’t expect anything drastic to happen with me not playing, but if I can get a conversation started in a majority-white sport I consider that a step in the right direction,” she wrote.

“Watching the continued genocide of Black people at the hand of the police is honestly making me sick to my stomach.”

At the U.S. Open that year, she wore a mask with the name of a different victim of police violence for her walk onto the court for each of her seven matches. When she won it, she lay down in the middle of Arthur Ashe and stared at the stars.

Eight months later, battling depression and anxiety, she endured a tumultuous summer, causing a stir at the French Open when she opted not to appear at news conferences, saying it was harming her mental health. Tournament organizers threatened to default her.

She withdrew instead and went on hiatus, appearing next at the Tokyo Olympics, where she lit the torch, a symbol of Japan attempting to embrace multi-culturalism. The weight of it all was a lot. When she lost early at the U.S. Open, she took an indefinite leave and questioned whether she wanted to keep playing. She played on and off in 2023, before getting pregnant with Shai, and returning to the tour at the start of this year.

GO DEEPER

Naomi Osaka and the cruelty of tennis comebacks

Swiatek has watched all this and taken cues from Osaka, as well as learning from her.

As soon as Russia invaded Ukraine, she began playing in a yellow-and-blue pin, the colors of Ukraine. She has helped raise millions of dollars for humanitarian relief for the war’s victims in Ukraine, as a neighbor and ally.

Mostly behind closed doors, she has been battling with leaders of the WTA Tour to try to claw back an element of freedom for top players to play when and where they want to that, something they partly lost this season. In Madrid, she said she had tried to pull back on politics and focus on her tennis, but keeps finding herself lured back in. On Wednesday, she touched another third rail — lightly scolding the French crowd for yelling during points, which she knows she may come to regret. No one likes to be scolded, especially when most players embrace the enthusiasm that makes Roland Garros what it is. Osaka said though the crowd was great, turning the heat of the spotlight squarely on Swiatek.

No surprise there. This is what happens to players at the top of the sport, and then they have to figure out what to do about it.

“I knew that I should be more focused and not let this distract me, but sometimes it’s hard,” Swiatek said later.

She was talking about the mid-point noise. She could have been talking about a lot more.

(Top photo: Tim Clayton/Corbis via Getty Images)