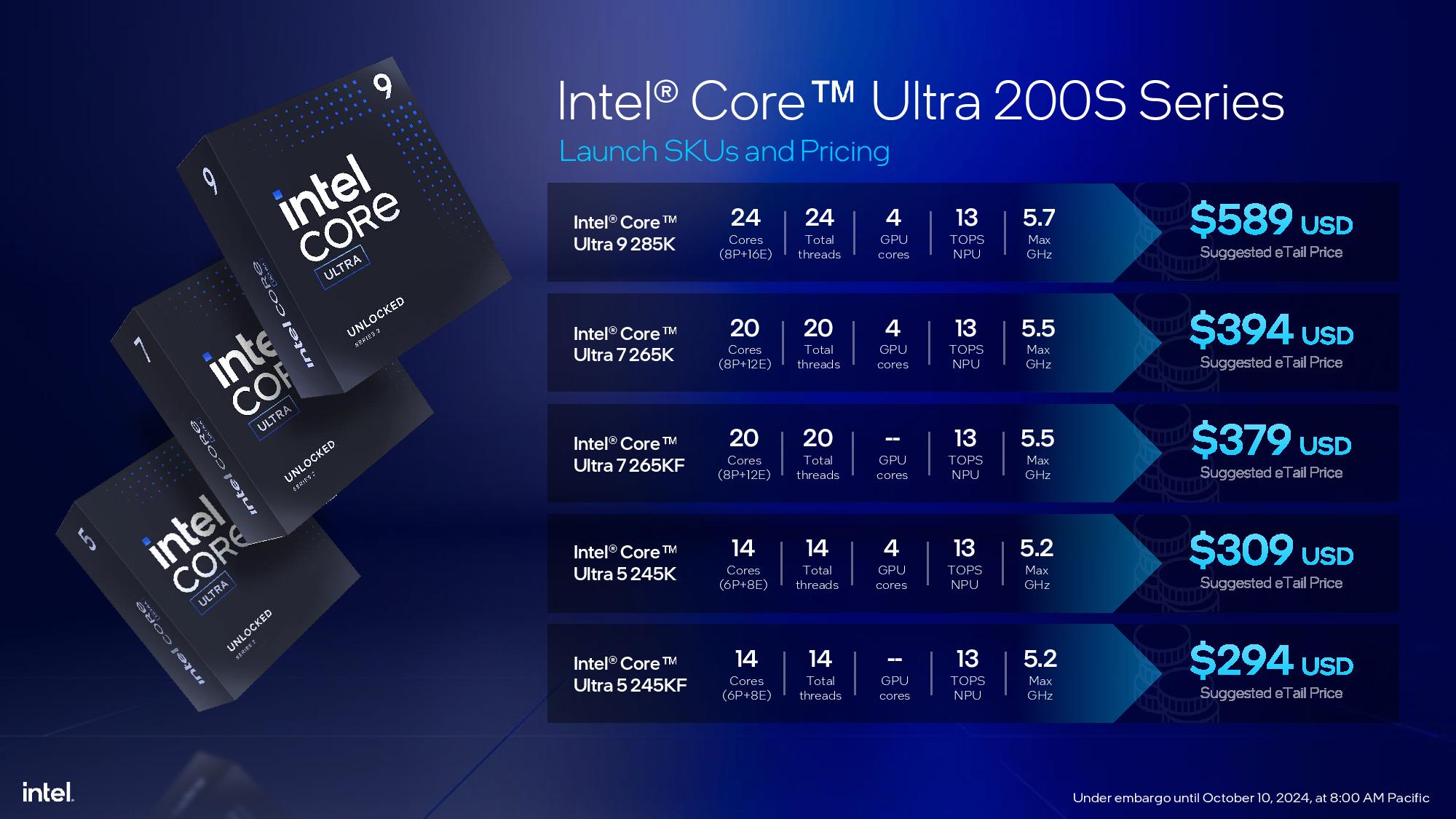

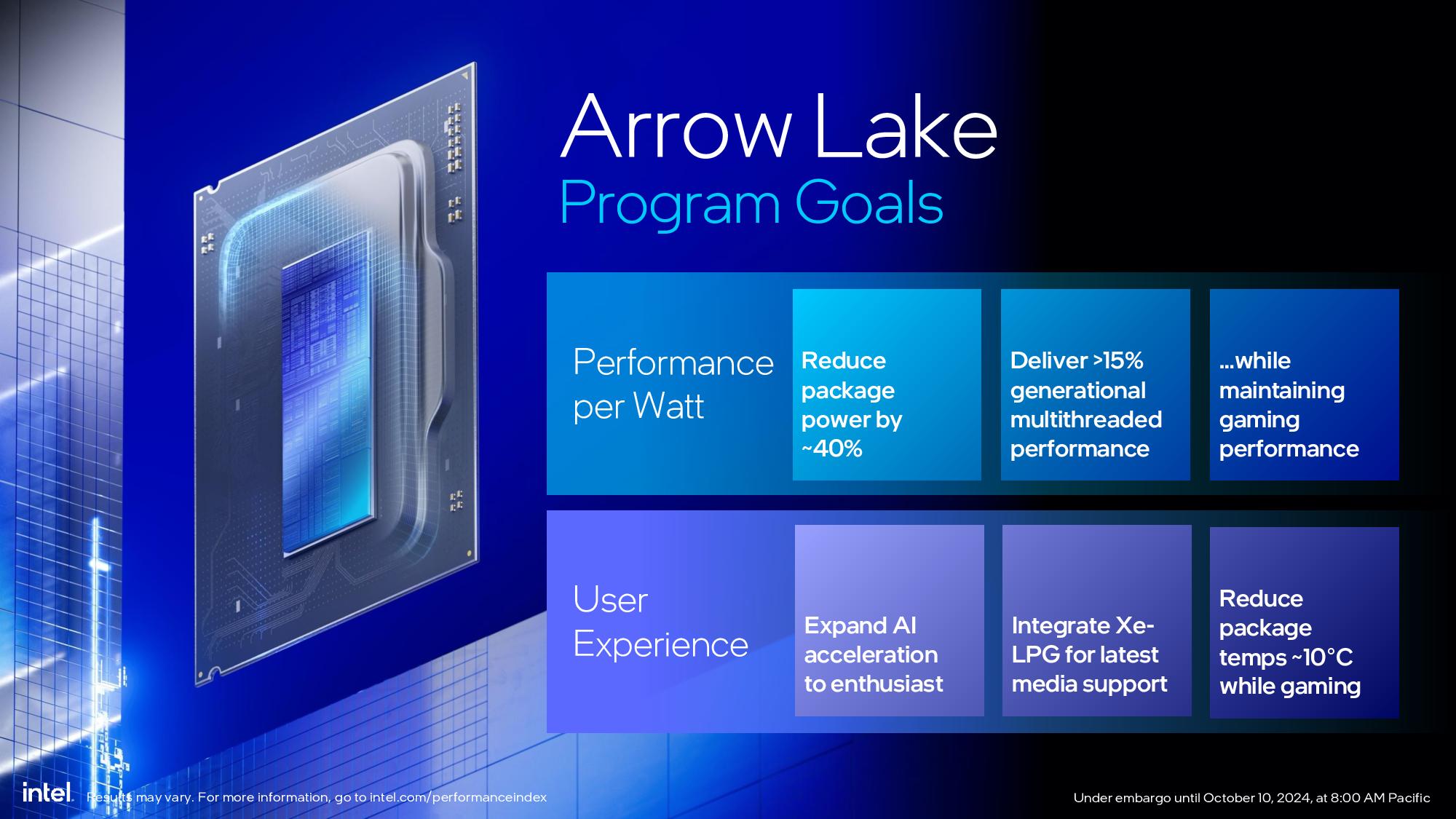

Intel announced the first five models of its Arrow Lake desktop processors, otherwise known as the Core Ultra 200S series, with prices ranging from the $294 14-core Core Ultra 5 245KF to the flagship $589 24-core Core Ultra 9 285K. The chips will come to market on October 24, 2024. Intel says Arrow Lake brings up to 15% more multithreaded performance, 5% more single-threaded performance, drastically reduced power consumption, and the first dedicated AI accelerator (NPU) in a mainstream desktop chip.

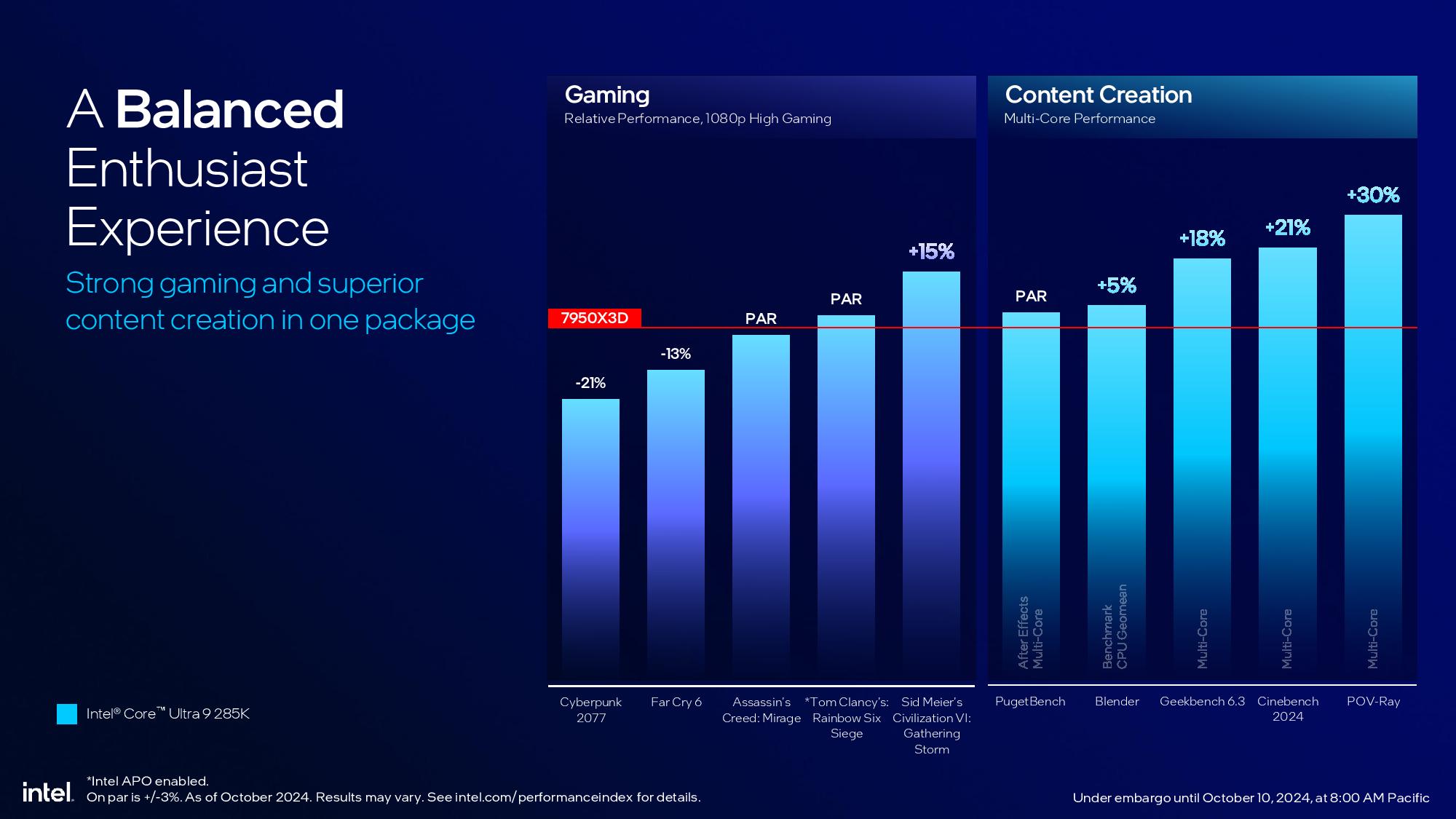

Surprisingly, things aren’t as positive on the gaming side of the equation. Intel says its new flagship Core Ultra 9 285K matches AMD’s flagship Ryen 9 9950X in gaming. However, according to our testing, Intel’s own current-gen 14900K flagship is 8 to 10% faster than the Ryzen 9, meaning Intel’s new Core Ultra 9 285K flagship could be slower in gaming than its own current-gen halo part. Additionally, Intel says that AMD’s fastest gaming-optimized chip, the Ryzen 7 7800X3D, is 5 to 7 percent faster than the Core Ultra 9 285K, but based on our 7800X3D tests and the relative positioning, the gap could be much larger.

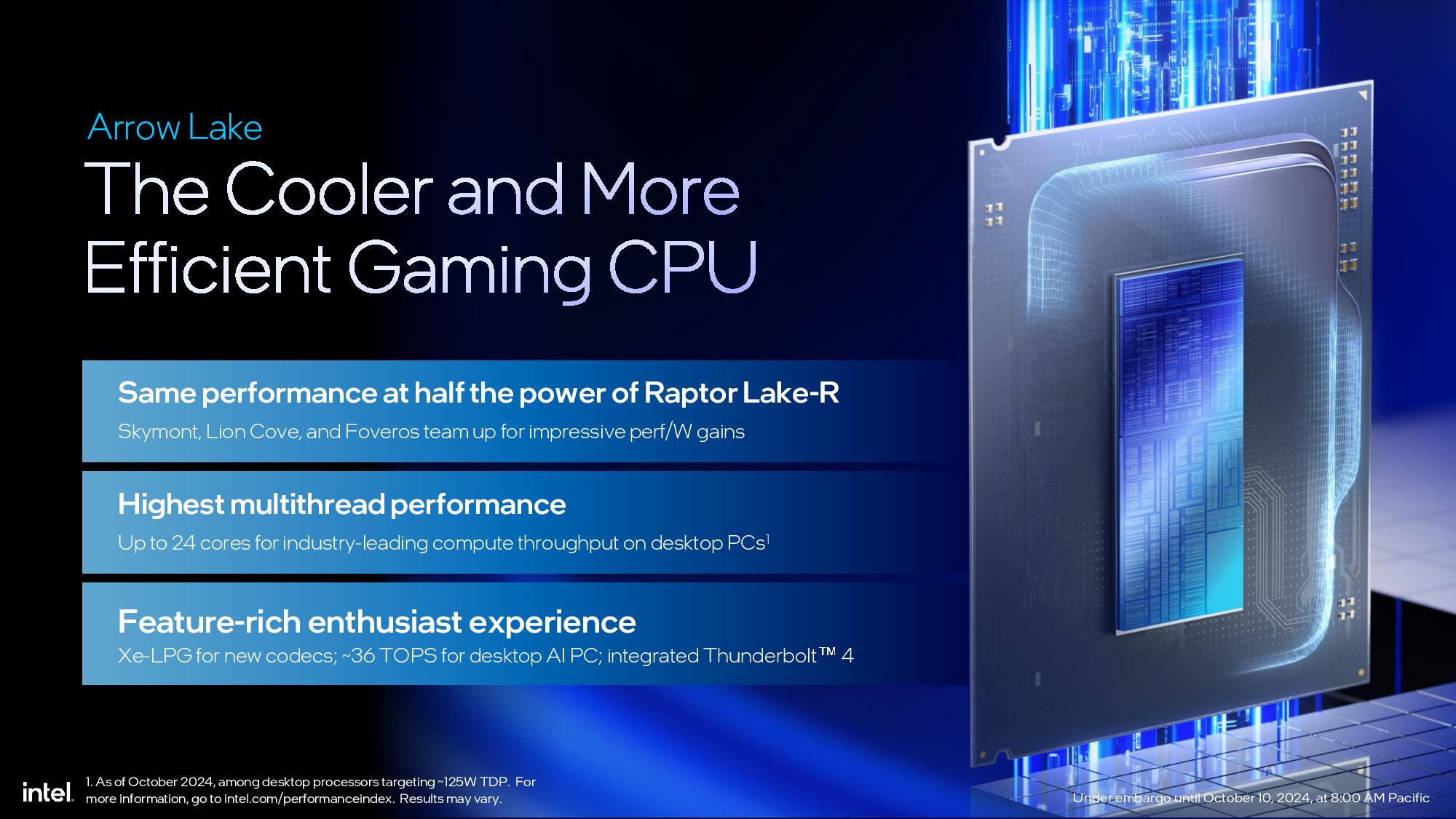

Of course, our testing will tell the final tale, and the mid-range processors could offer a stronger value proposition. After AMD’s lackluster gen-on-gen gaming improvements with its mainstream Zen 5 chips and Intel’s lower predictions for the new Ultra 9, Intel’s new lineup makes it look like we’ll have to wait for the looming AMD Ryzen 9000X3D processors for any (potential) gains in top-tier gaming performance this year. That leaves Arrow Lake’s higher performance in productivity applications and drastic power reductions. Intel claims up to a 165W decline in total system power in gaming, resulting in 10C lower operating temperatures on average as the key Core Ultra 200S key selling points.

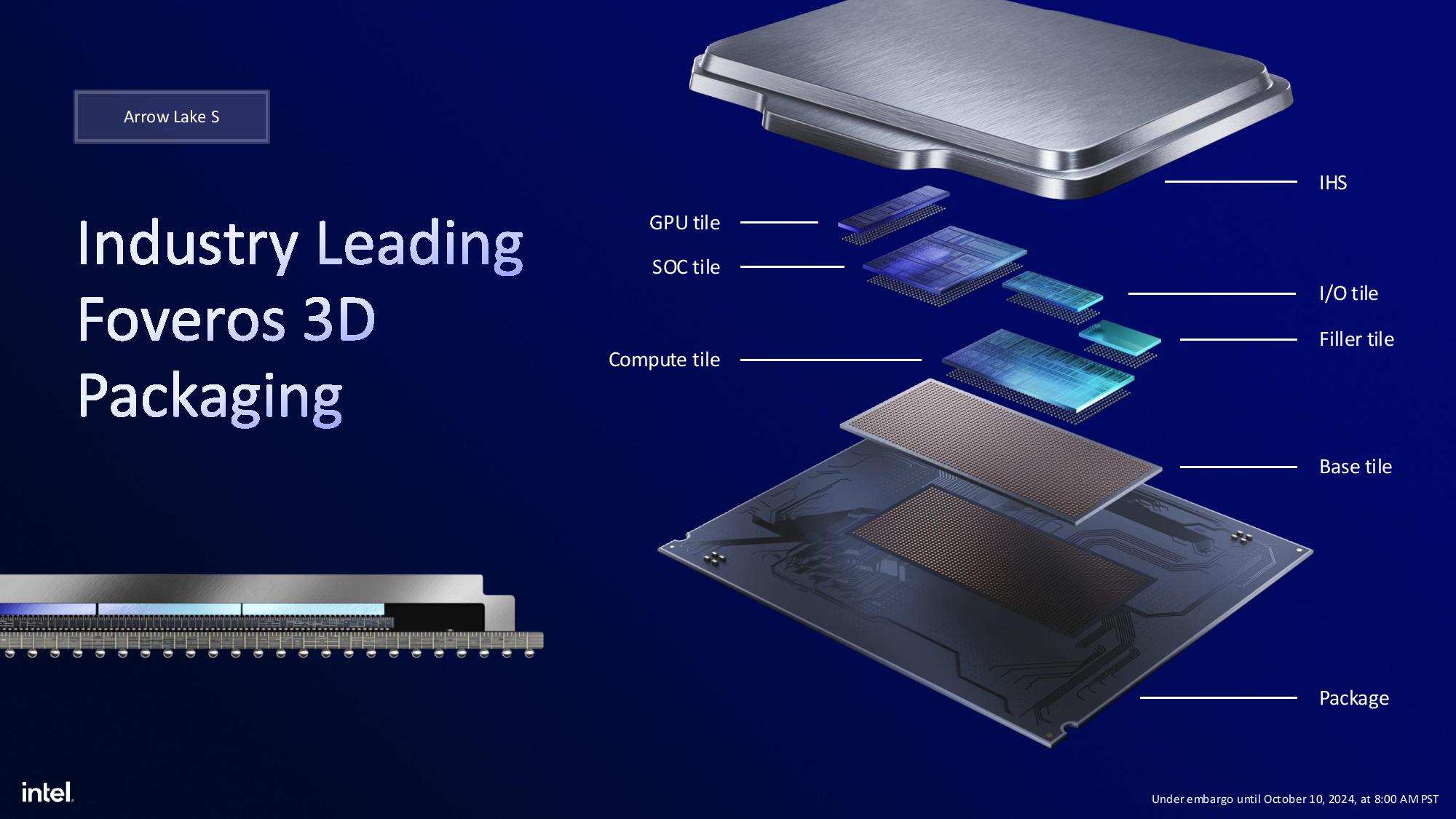

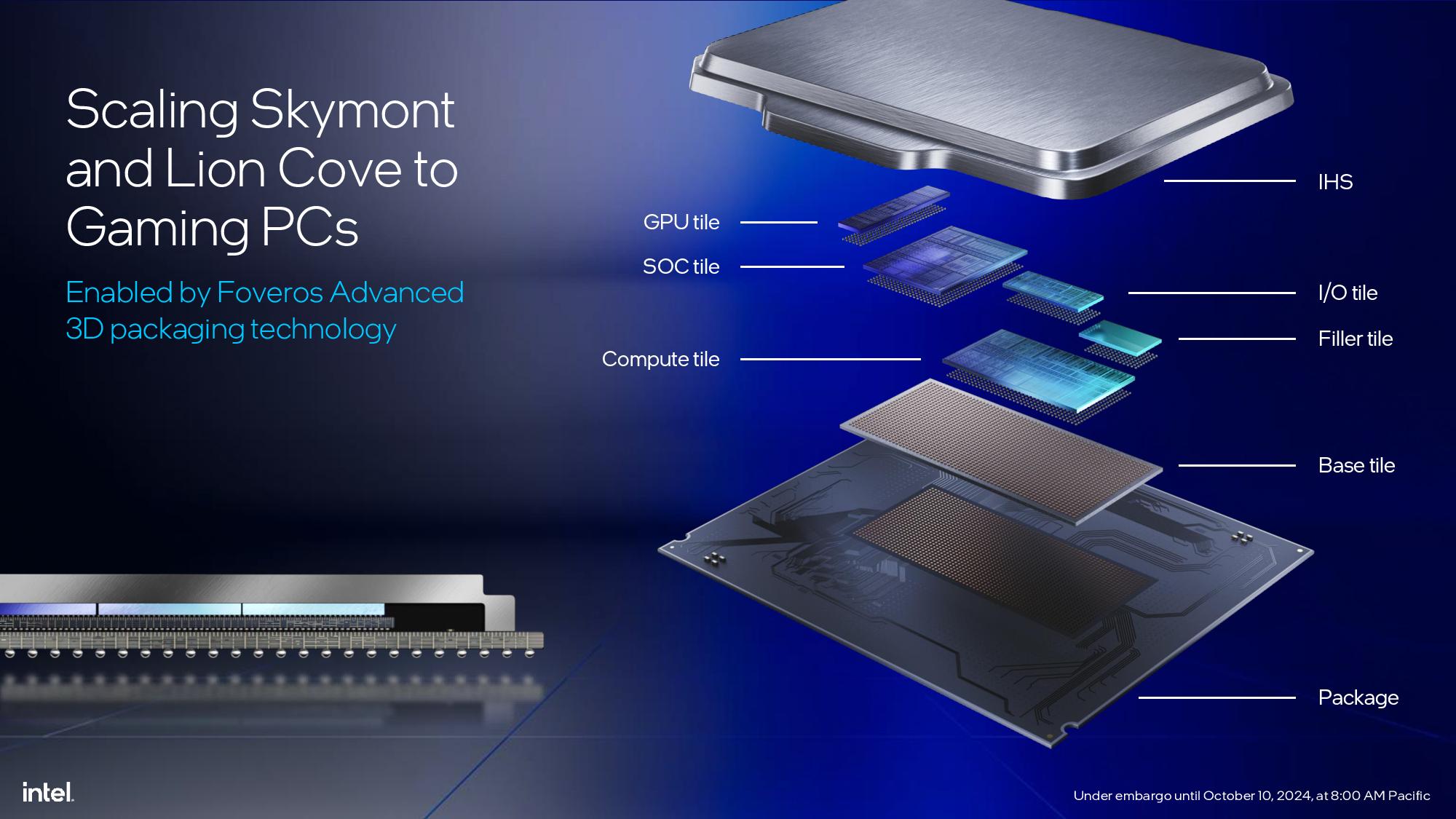

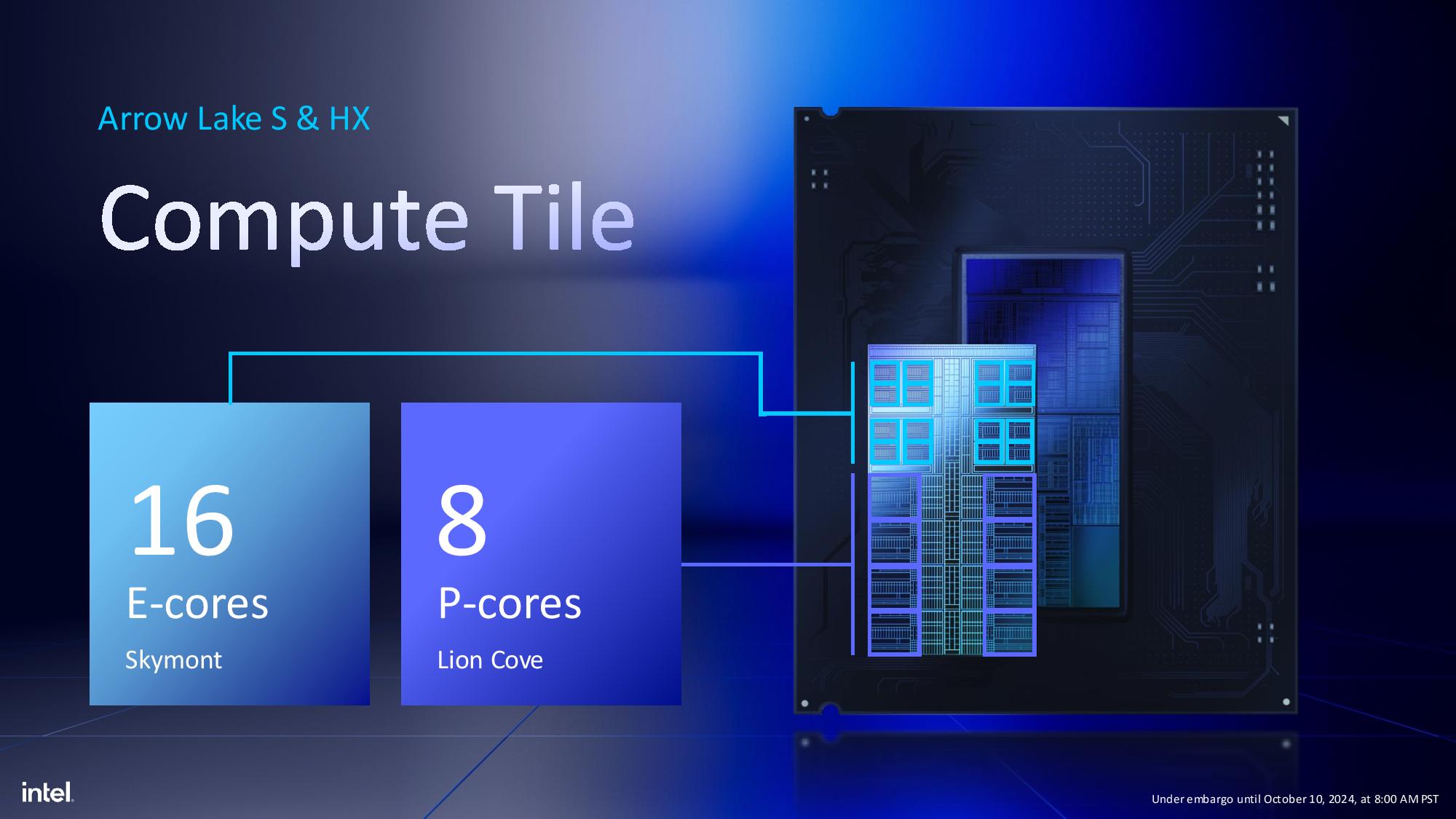

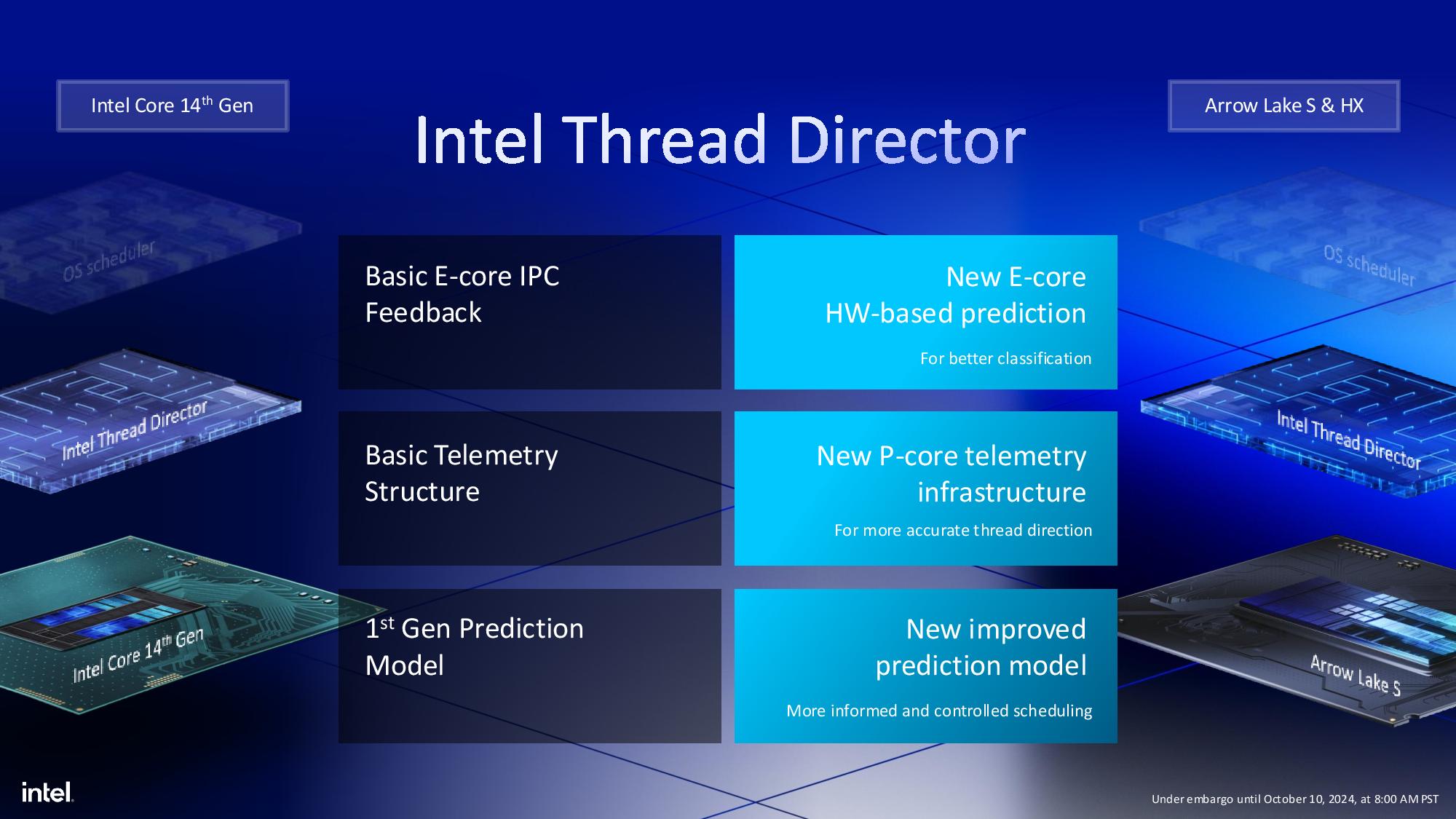

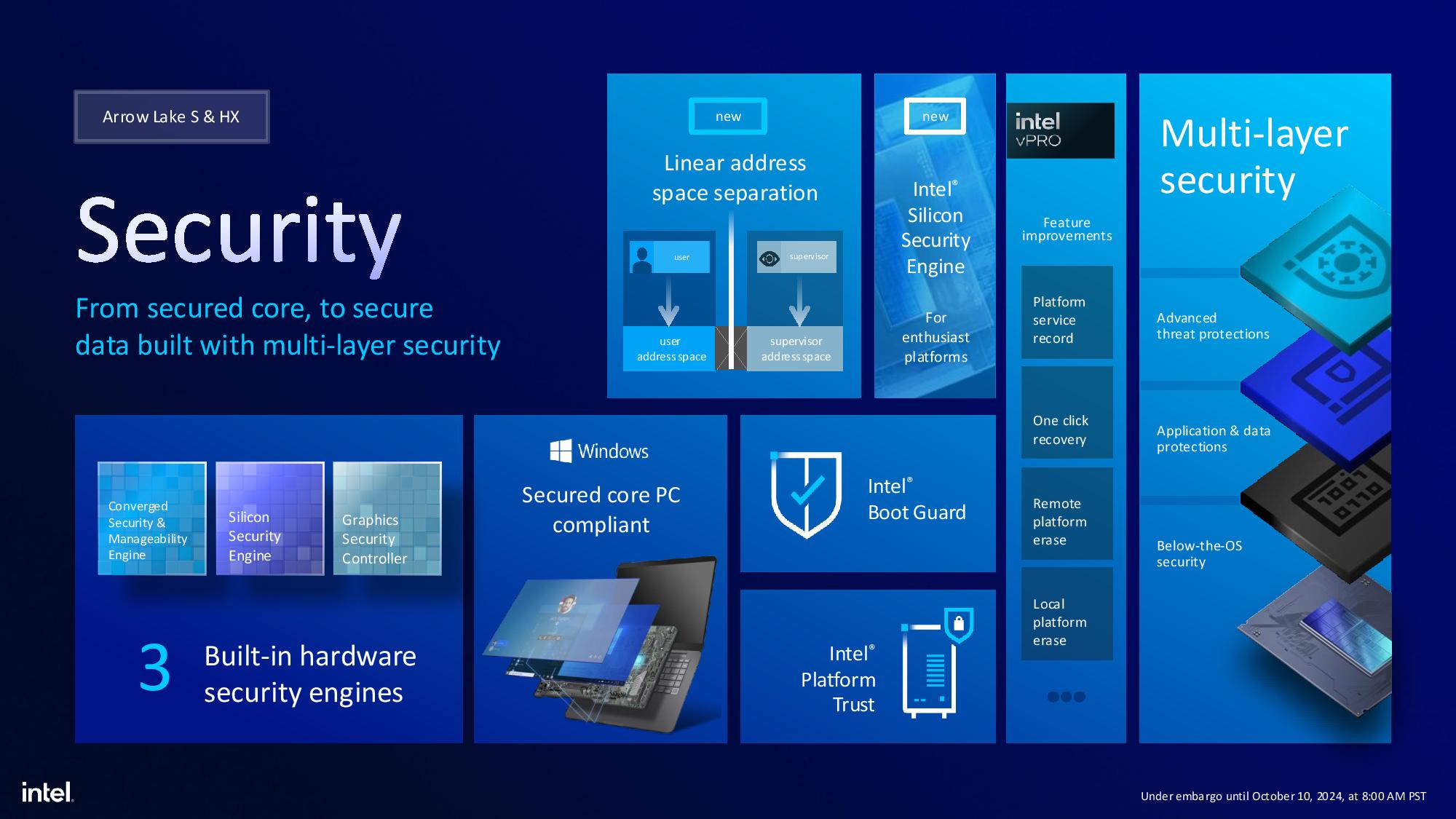

The Core Ultra 200S series has plenty of other innovations, too. Arrow Lake has new architectural design elements for desktop PCs, including a five-chiplet design that leverages cutting-edge Foveros 3D packaging in tandem with a radically redesigned compute tile that intersperses Skymont E-core clusters among the Lion Cove P-cores. Intel also discarded Hyper-Threading and support for both DDR4 and DDR5 memory like it had with the prior-gen Raptor Lake processors, instead going with only DDR5 while adding support for the new CUDIMM DDR5 modules that boosts easily attainable memory overclocking speeds to DDR5-8000 (and beyond). Intel also has new overclocking knobs for enthusiasts and a new 800-series chipset.

Besides these desktop parts, Intel announced that its Core Ultra H and HX series for enthusiast-class laptops are coming to market in the first quarter of 2025. There’s a lot of ground to cover. We’ll start with the SKUs and move directly to the performance claims, then cover the new architectural components.

Intel Arrow Lake Core Ultra 200S specifications and pricing

Intel has switched to the same ‘Core Ultra’ branding it uses for the mobile market but uses the ‘S’ suffix to differentiate the desktop models. Intel begins the series at ‘200S’ instead of ‘100S,’ which a representative said “makes sense” without elaborating. Considering the Core Ultra 100-series was Meteor Lake, we assume it was a reference to Arrow Lake having more in common with the Lunar Lake 200-series parts.

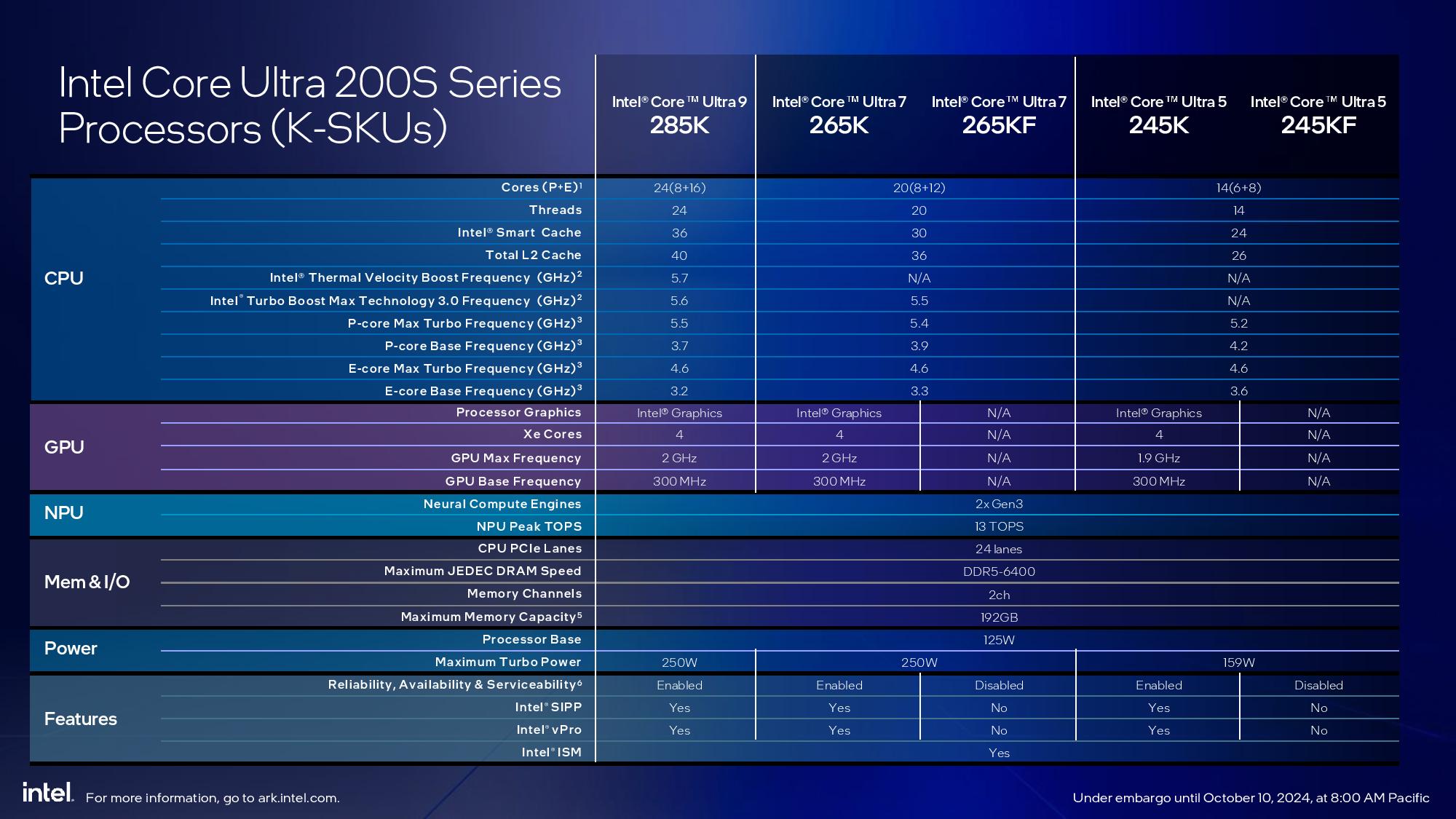

The five Arrow Lake SKUs slot into the Ultra 9, 7, and 5 families with 24, 20, and 14 cores, matching their prior-gen counterparts. However, the P-cores no longer support Hyper-Threading so the total thread counts are lower. Intel says it has actually increased performance in multi-threaded workloads despite the removal of Hyper-Threading. Intel has the standard overclockable K-series models along with two KF-series chips that come without the integrated graphics engine, so you can save some cash on the two lower-end models if you plan to use a discrete GPU. Intel doesn’t have a KF option for the Ultra 9 285K, but a representative said that could be an option in the future.

Intel’s Ultra 9 weighs in at $589, matching the launch day pricing of its previous-gen 14900K counterpart. The $394 Ultra 7 265K debuts for $15 less than the previous-gen Core i7-14700K it replaces, while the $309 Core 5 245K is $10 less than the prior-gen Core i5-14600K. These chips line up against the same competing AMD Ryzen 9000 processors as their prior-gen counterparts did, as outlined in the above table (detailed specs are also in the prior album).

Intel dropped peak clock speeds across the board, with the Ultra 9 weighing in at 5.7 GHz, 300 MHz less than the prior gen, while the Ultra 7 and 5 get 100 MHz reductions in boost speeds. However, Intel has adjusted P-core base clocks upward by 500 to 700 MHz. The E-cores have also seen 200 to 600 MHz improvements in boost clocks, and 600 MHz to 1 GHz improvement in base clock speeds.

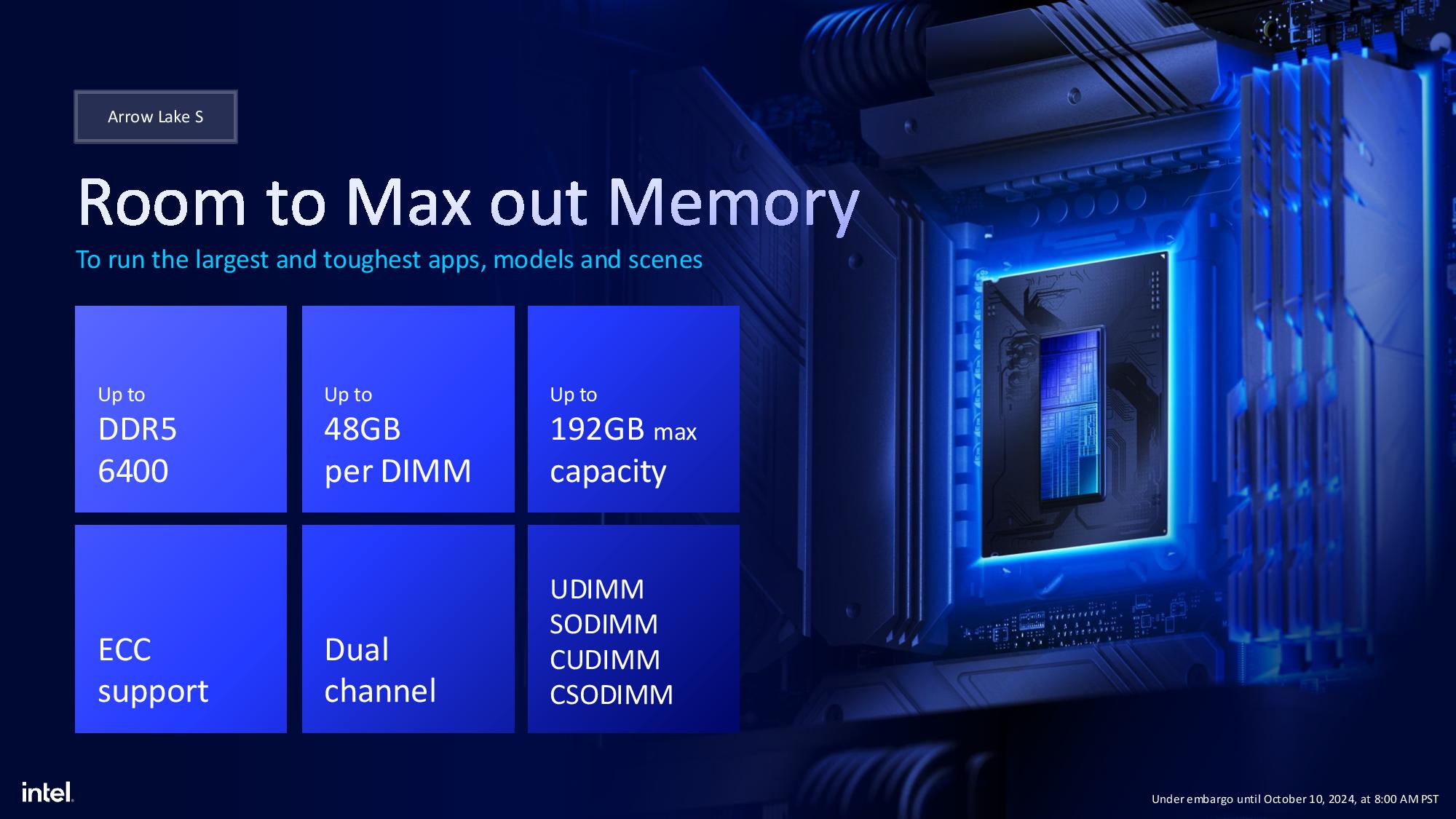

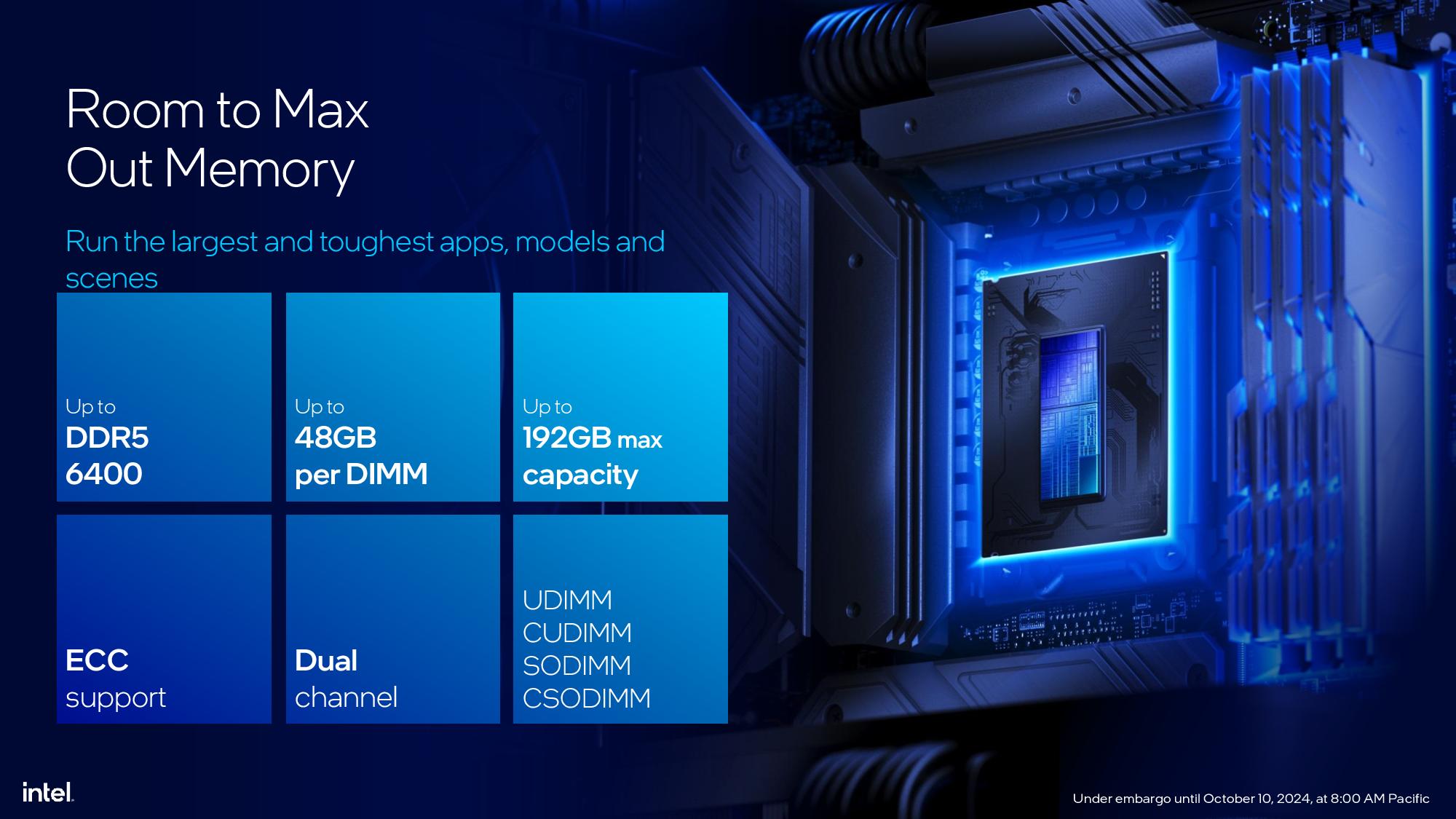

Intel supports up to 192GB of DDR5-6400 with DDR5 CUDIMMs, a new type of DIMM that comes with an integrated clock redriver that boosts easily-attainable stable clock frequencies by stabilizing the data eye. Intel also points to much higher overclocking headroom with CUDIMMs and says DDR5-8000 appears to be the sweet spot. We’re awaiting more detailed memory specs, such as the base memory frequency with standard DDR5 DIMMs and clock speeds based on the number of DIMMs per channel (as before, the processors support dual channel). Arrow Lake does support ECC memory, but it won’t be supported on consumer platforms — instead, that’s reserved for enterprise systems.

Despite Arrow Lake’s claimed lower operating power consumption, the chips still come with similar maximum TDP ratings of 250W for Ultra 9 and 7 (3W less than Raptor Lake), and 159W (22W less) for the Ultra 5. Intel says the lower power consumption occurs during normal workloads with an up to 40% reduction in package power consumption, which we’ll expand on below. Intel also increased the maximum CPU temperature (TJMax) to 105C for Arrow Lake, a 5C higher limit.

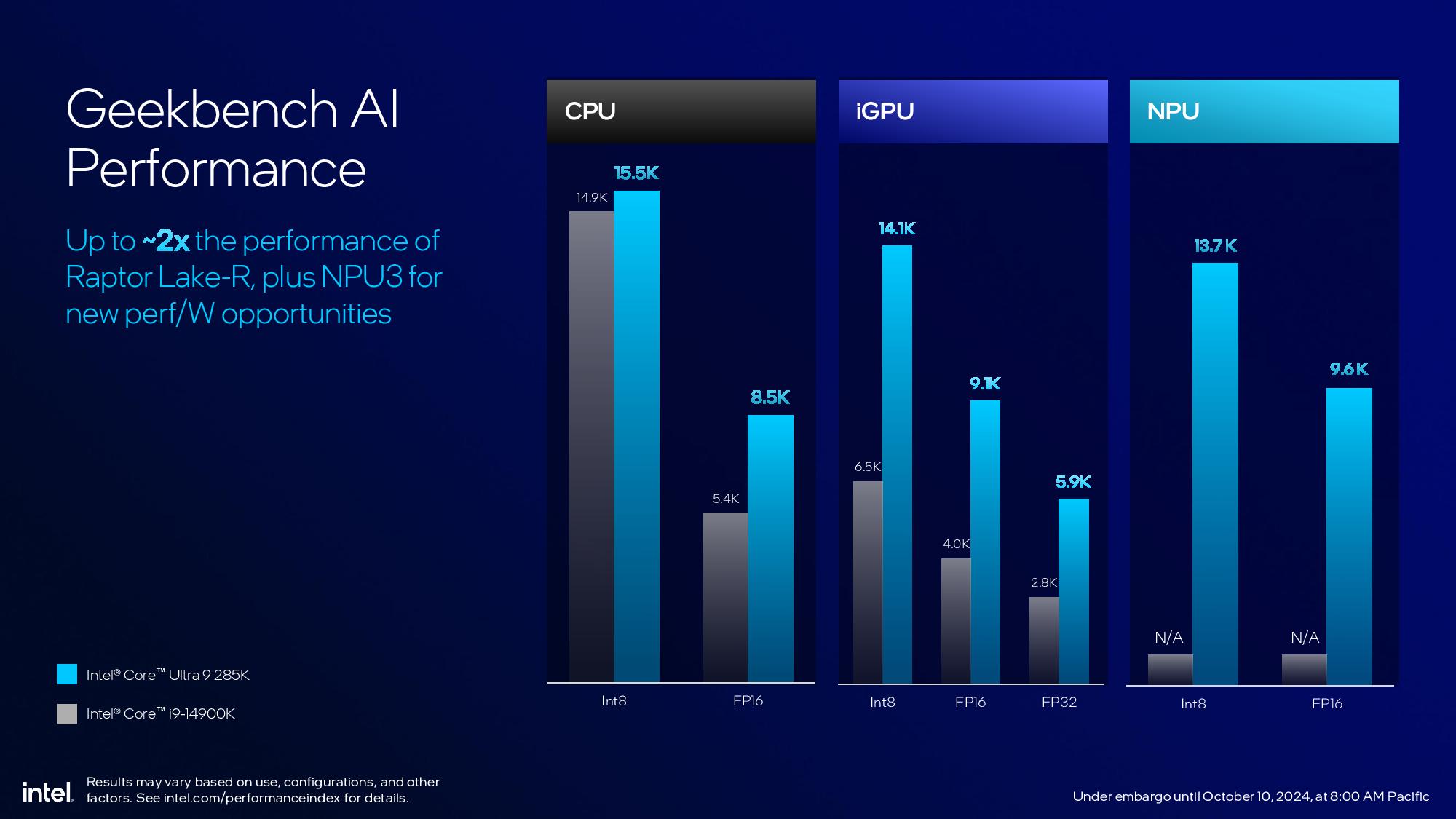

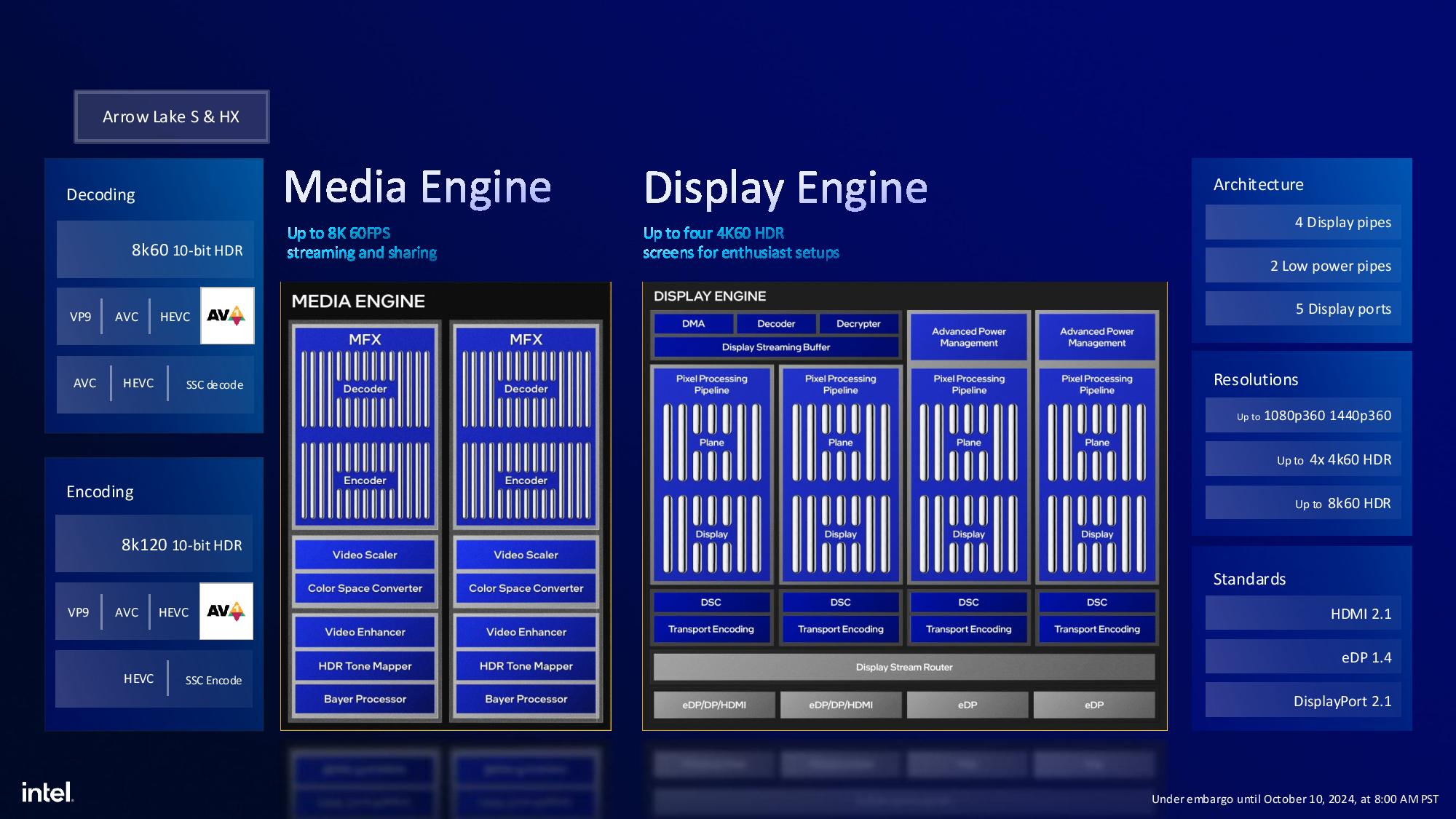

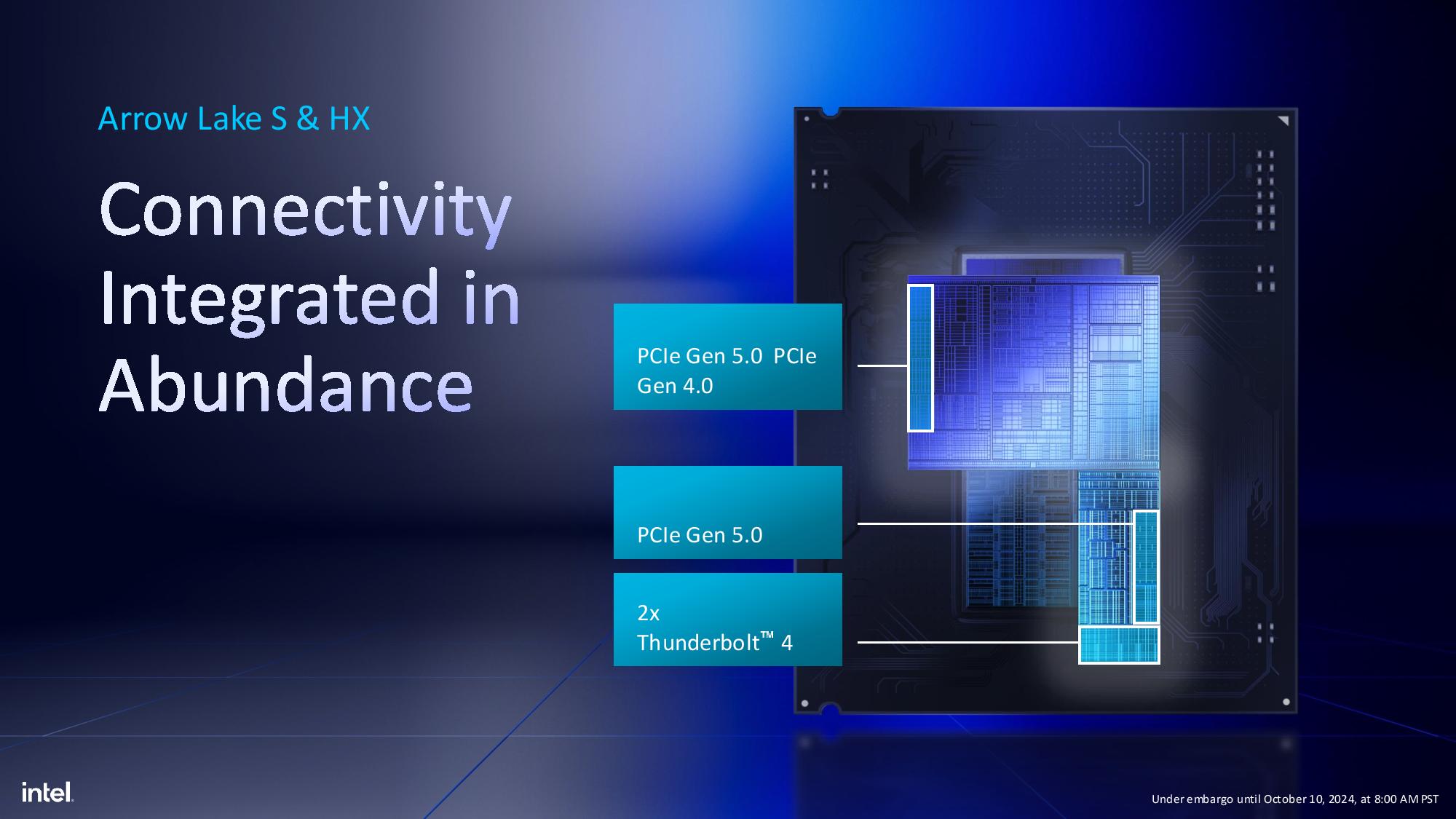

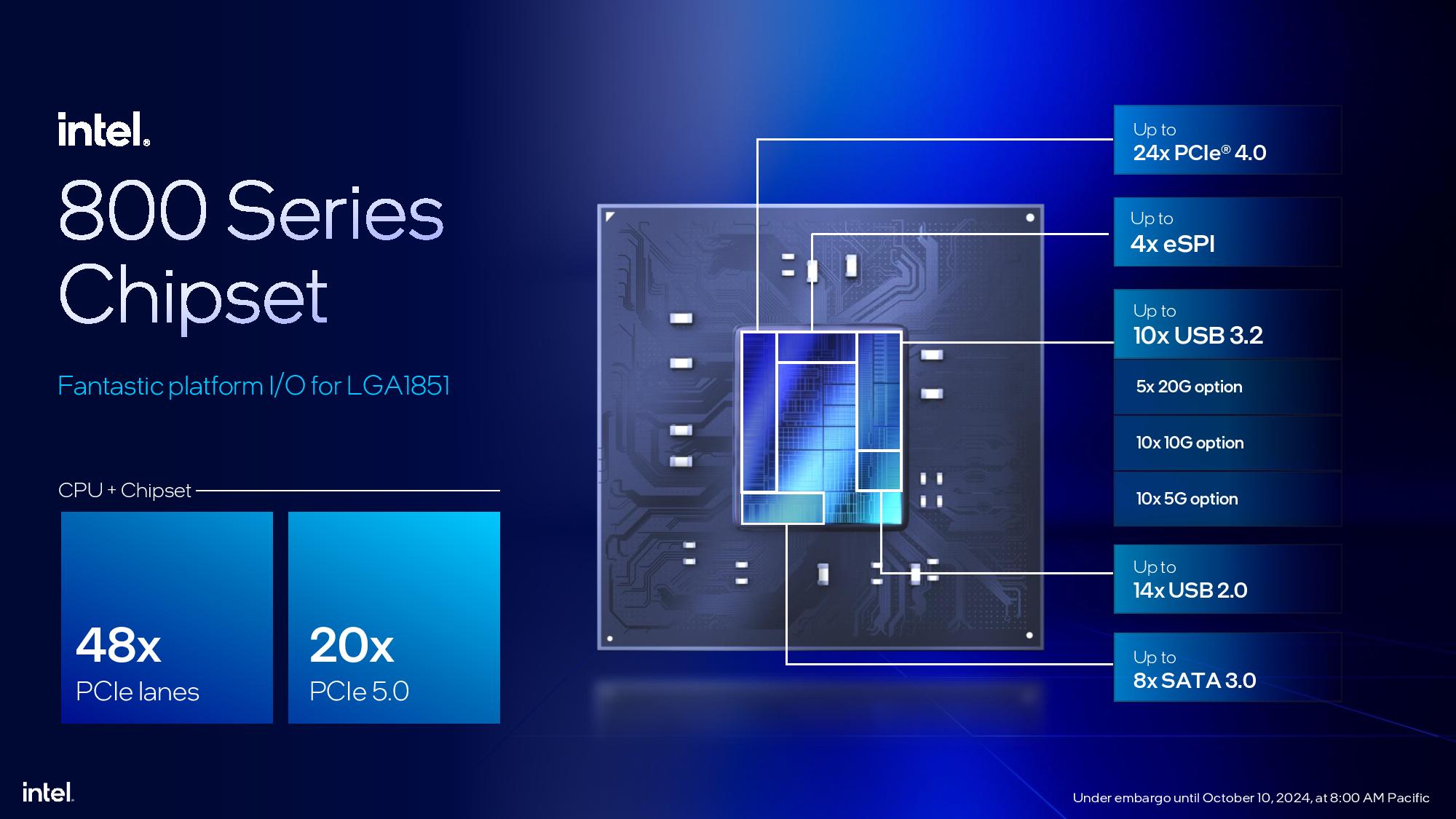

All three K models come with 24 lanes of PCIe 5.0, with an additional 20 lanes of PCIe 4.0 provided by the chipset. The Ultra 9, 7 and 5 all come with the same Xe-LPG graphics engine with 4 Xe cores as the Meteor Lake chips, not the newer Battlemage Xe2 engine found in Lunar Lake, with the Ultra 9 and 7 sporting a 2.0 GHz graphics boost clock, while the Ultra 5 drops to 1.9 GHz. Intel says the iGPU offers twice the performance of the graphics on the 14th-gen processors.

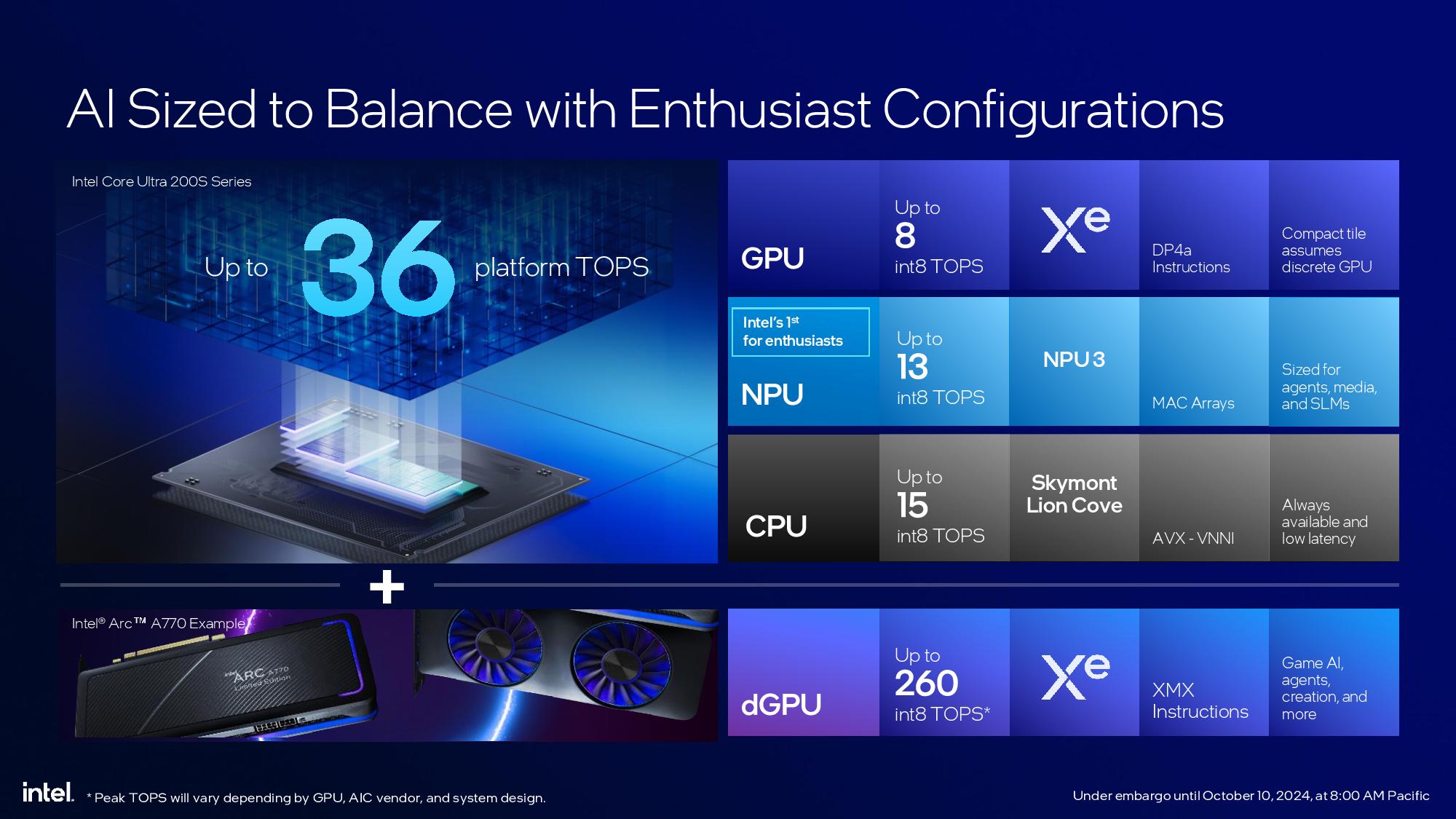

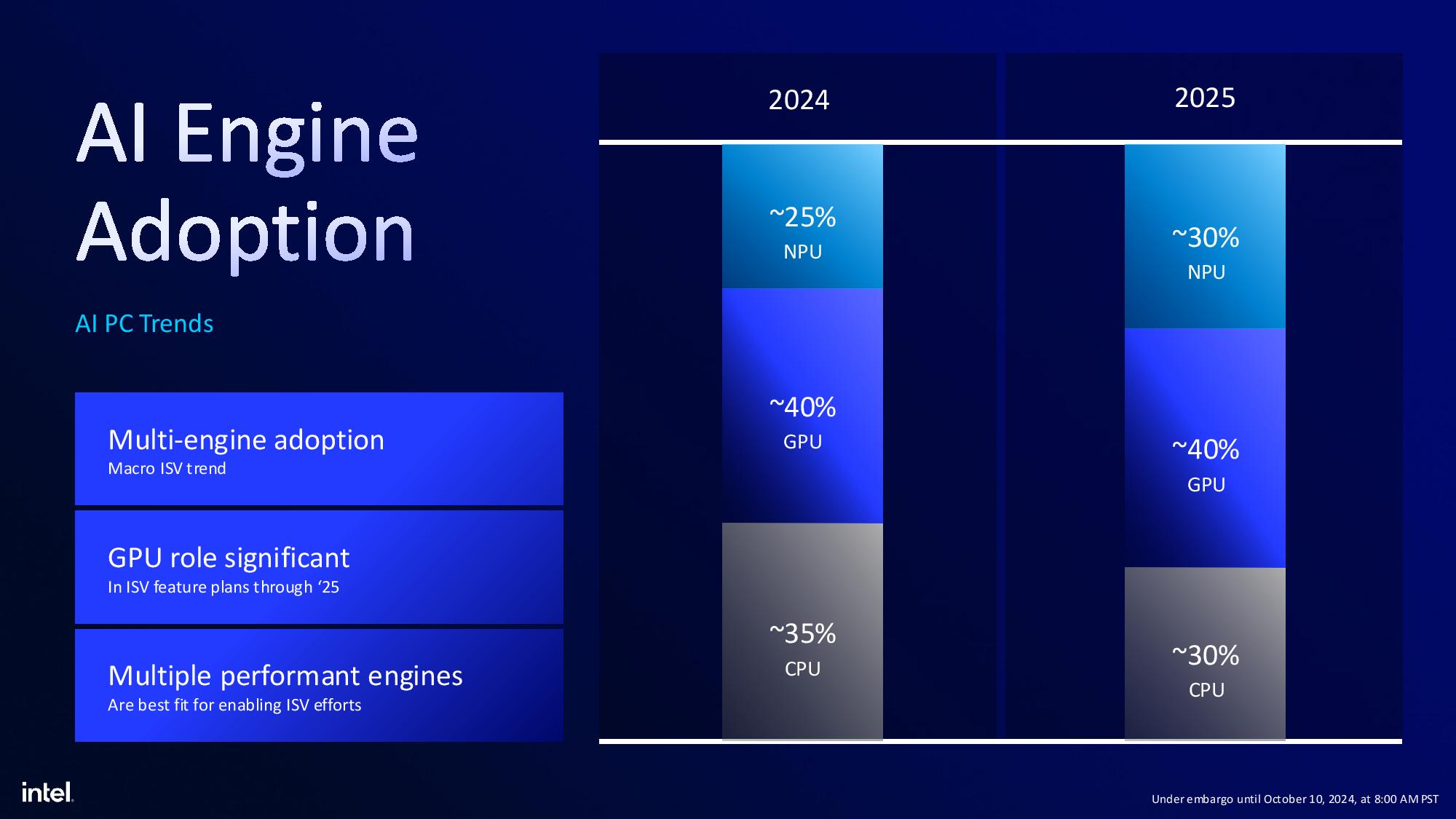

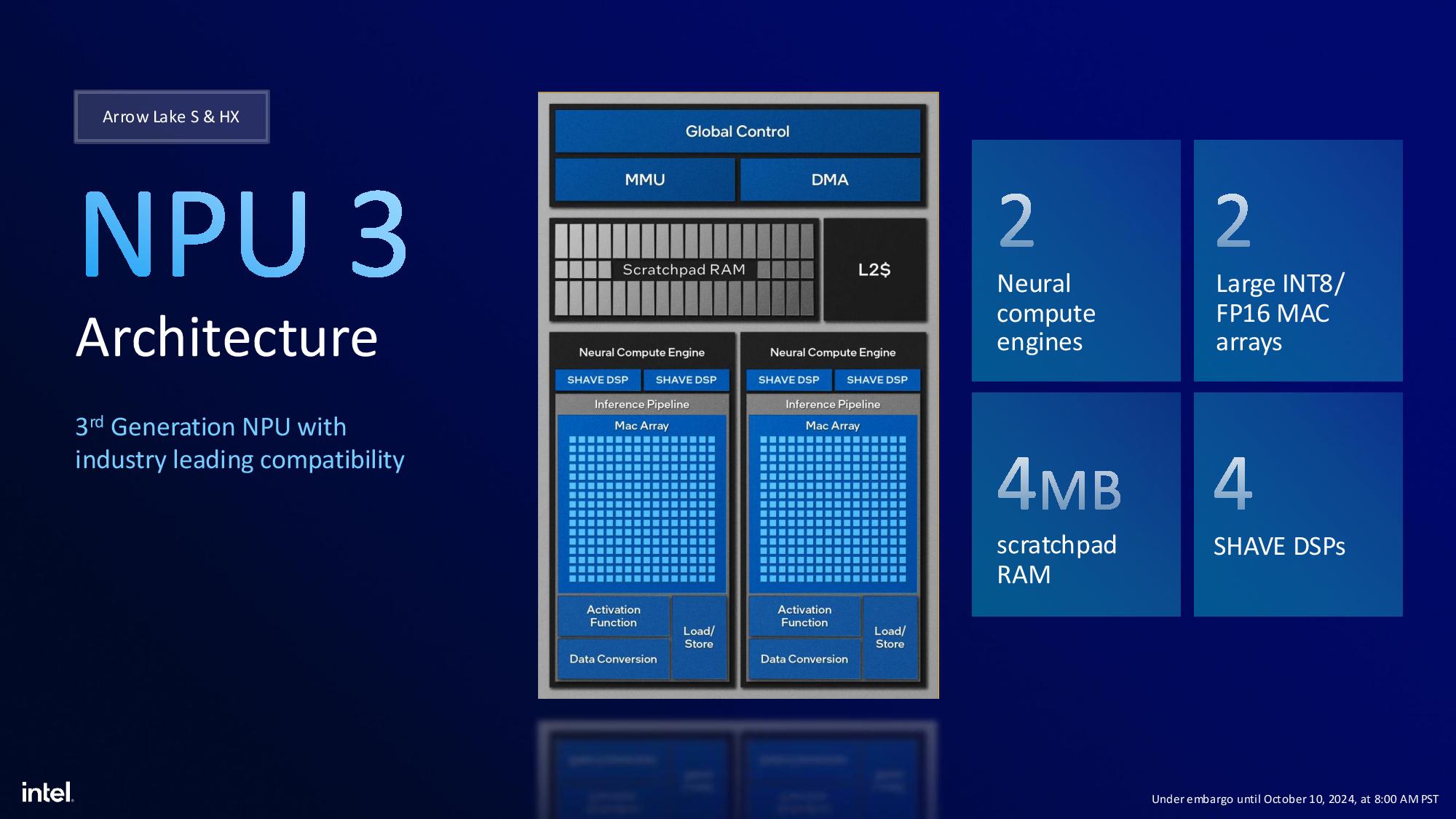

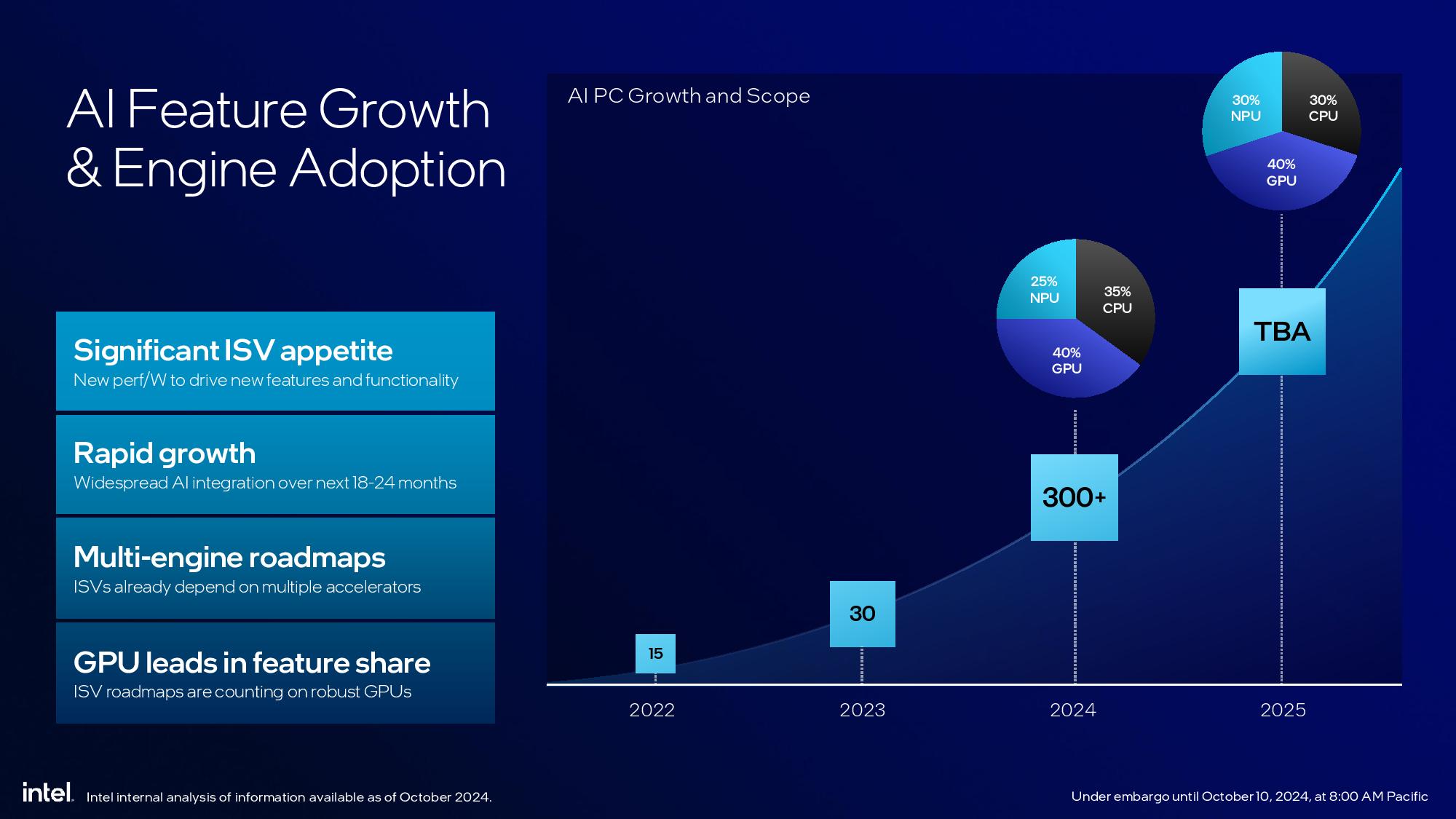

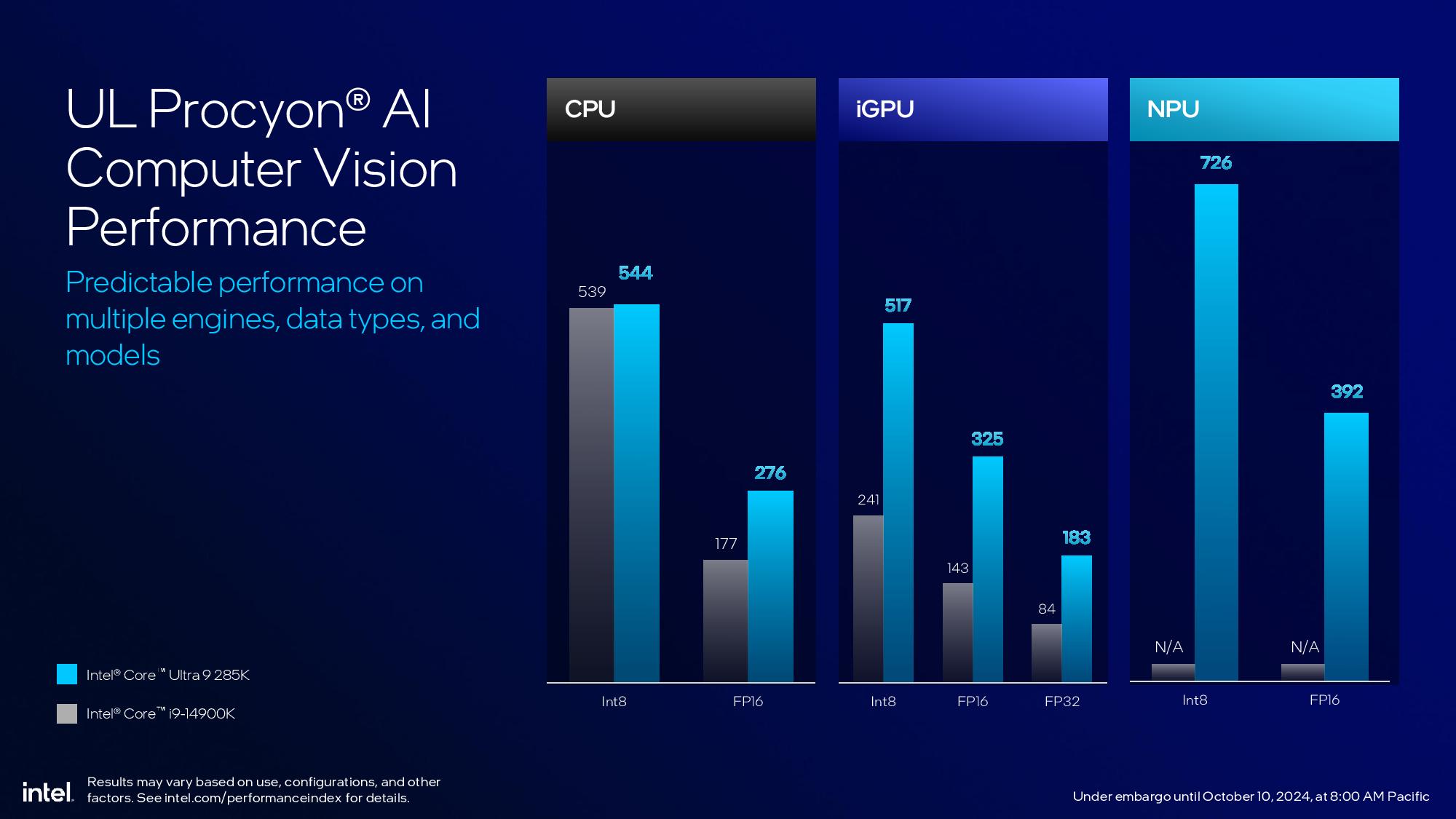

The chips also feature the same NPU engine for AI acceleration as Meteor Lake, not Lunar Lake. This engine provides up to 13 TOPS of INT8 throughput, which doesn’t meet Microsoft’s CoPilot+ requirement of 40+ TOPS. Intel says it decided to go with the smaller engine to balance the die area requirements — a larger engine would chew into the space available for other additives, like cores and cache. Frankly, considering most desktop interested in AI will have a dedicated GPU they can leverage, the presence of a relatively low performance NPU hardly seems to matter. Increasing power efficiency for AI workloads on a desktop while drastically cutting potential performance — an RTX 4060 as just one example offers 242 TOPS of compute — just isn’t a critical factor.

The chips drop into the LGA 1851 socket, so they are not compatible with existing motherboards. Existing coolers should be compatible with the requisite mounting hardware, but the need for a kit could vary by vendor. Unlike AMD, Intel won’t commit to using the LGA 1851 socket for future processor generations, simply saying that it doesn’t comment on potential future products. That could mean that LGA 1851 will end up as a single generation socket.

Intel Arrow Lake Core Ultra 200S gaming benchmarks

Here we can see Intel’s gaming performance claims against AMD’s Ryzen 9000, but as always, view these vendor-provided benchmarks with caution. Intel used its Application Optimizer (APO) software for these tests, so results will be lower without that software enabled. We provided the test notes in an album at the end of the article. We’ll also explain the cause of the lower-than-expected gaming benchmarks in the architecture section.

Intel says its new flagship Core Ultra 9 285K matches AMD’s flagship Ryzen 9 9950X in gaming, but AMD’s chip is about 10% slower than Intel’s current-gen Core i9-14900K, so the new flagship Core Ultra 200S series should be slower in gaming than Intel’s prior-gen 14900K flagship. Making matters even more challenging for Intel, AMD’s fastest specialized gaming chip, the Ryzen 7 7800X3D, is 15 to 20% percent faster in gaming than the 9950X in our own tests. However, Intel says the 285K will only lag the 7800X3D by ‘5 to 7%,’ which doesn’t add up based upon real-world testing of the 7800X3D and its relative positioning to the 9950X.

As you can see, the 285K trails the 9950X by up to 13% in Cyberpunk 2077, and also trails in four other titles. Intel’s benchmarks show the 285K matching 9950X in six titles while beating it in four additional titles. However, the large +28% advantage in Total War: Warhammer III is in the Mirrors of Madness benchmark that stresses the CPU cores in an almost synthetic type of workload. The size of this single outlier also influences the average performance heavily, so we could see the 285K come in lower overall than the 9950X in various reviewer test suites.

Intel also provided a very narrow selection of five gaming benchmarks against the 7950X3D, showing that it significantly lags in two of the benchmarks while having a 15% advantage in one title. We expect the deltas will be in the 7950X3D’s favor in a larger range of titles. In the same slide, Intel points to its strong performance advantage over the 9950X3D in a range of heavily-threaded productivity workloads, like Blender and Cinebench, as a proof point of its balanced level of performance.

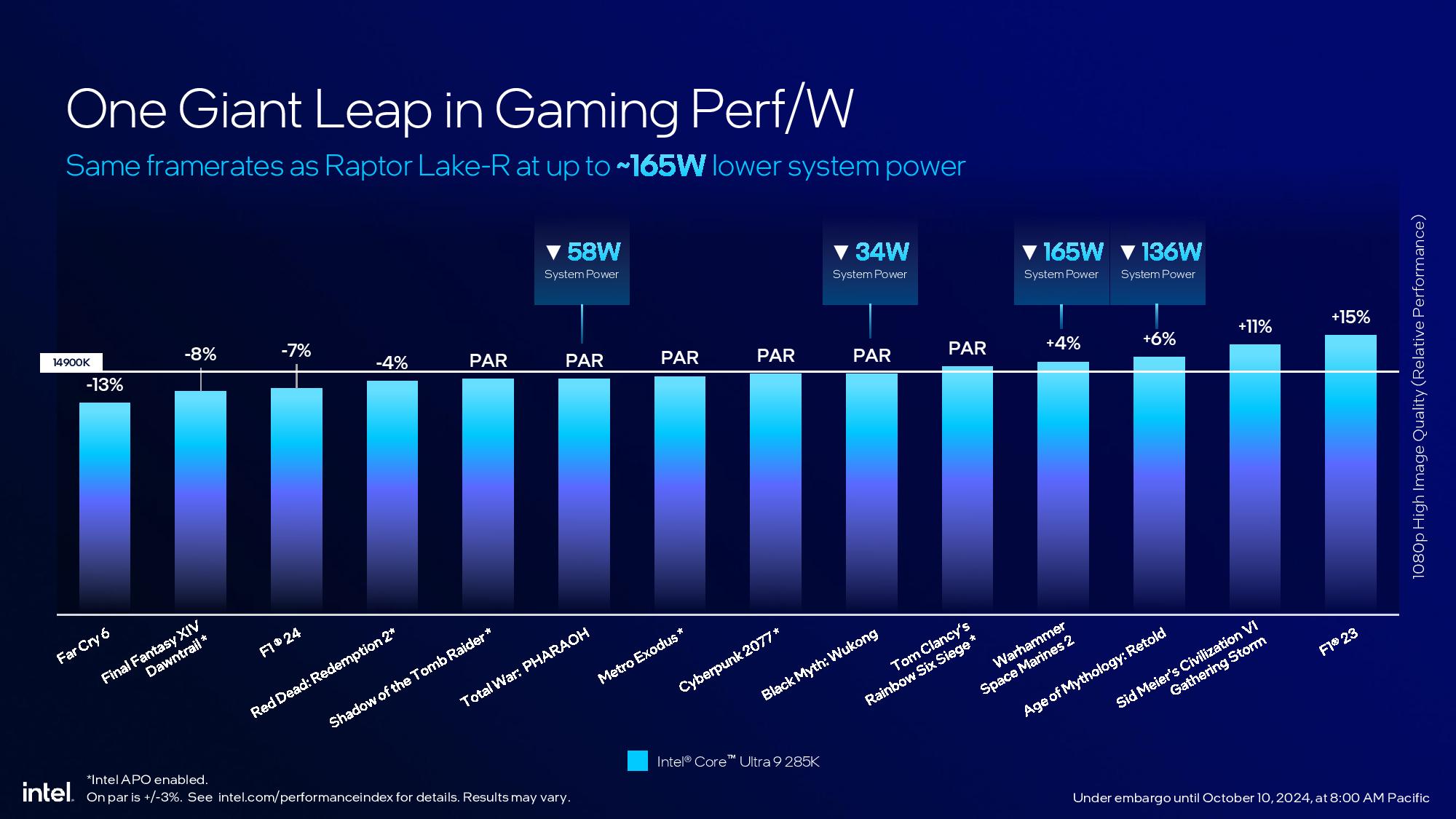

Intel also teased the Ultra 7 265K as offering roughly 5% less performance than the 14900K, but at up to 188W lower power consumption and 15C lower temperatures (geomean). Intel didn’t provide any benchmarks to substantiate those claims. Intel is also keen to point out its lower power consumption metrics in gaming, which we’ll cover below, but only included comparisons to its own prior-gen chips, not AMD’s Ryzen 9000.

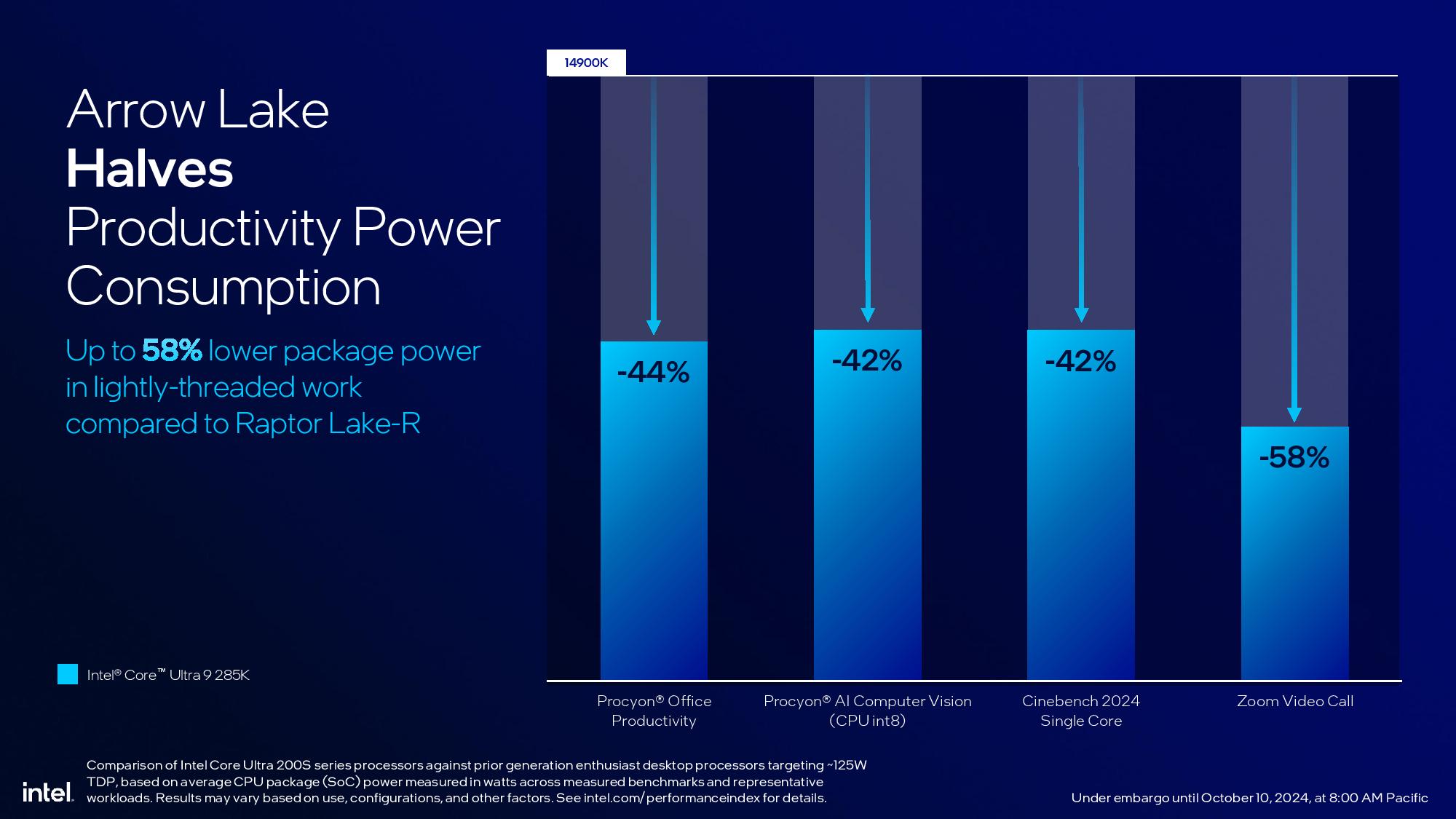

Intel Arrow Lake Core Ultra 200S power consumption improvements

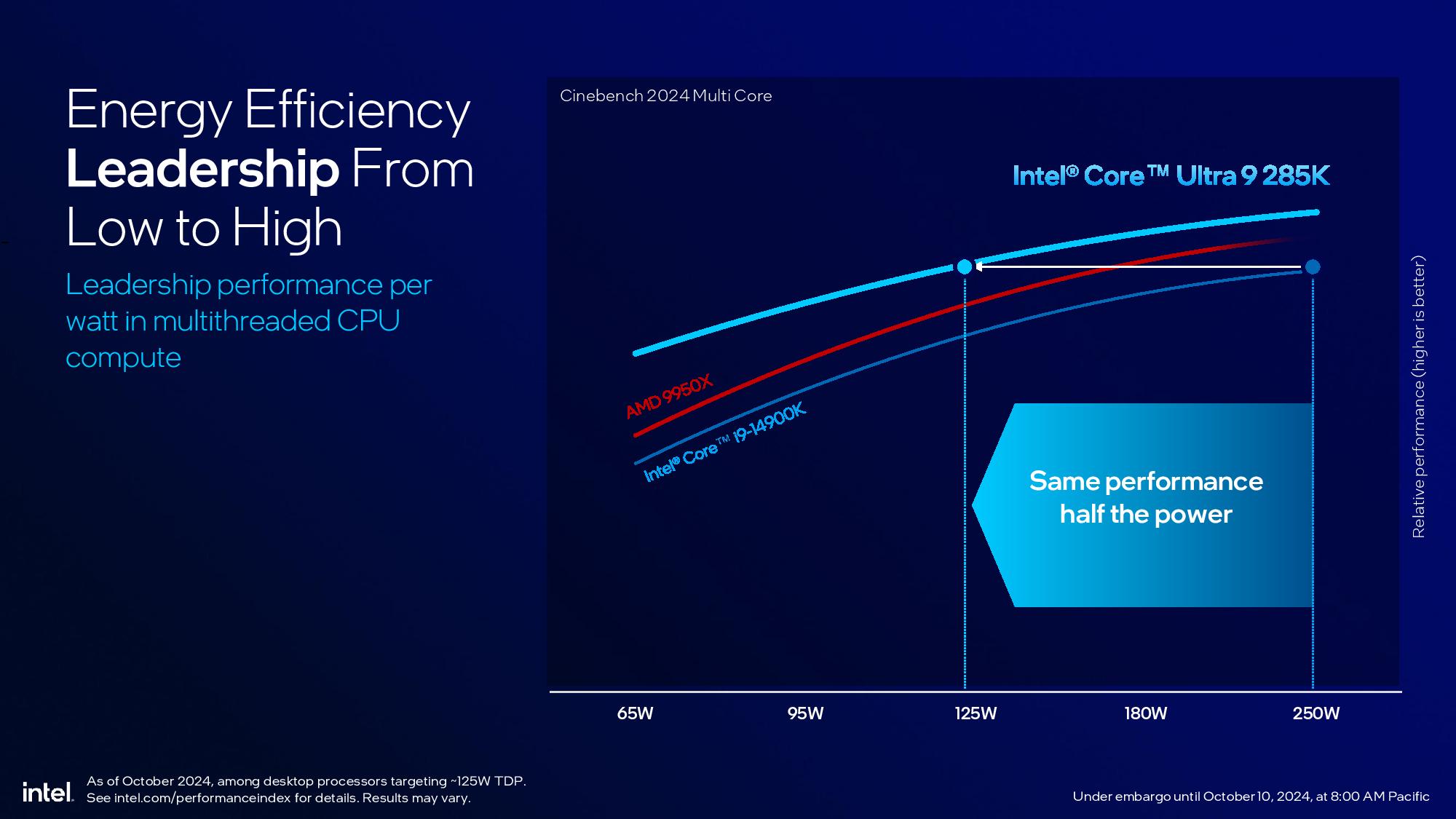

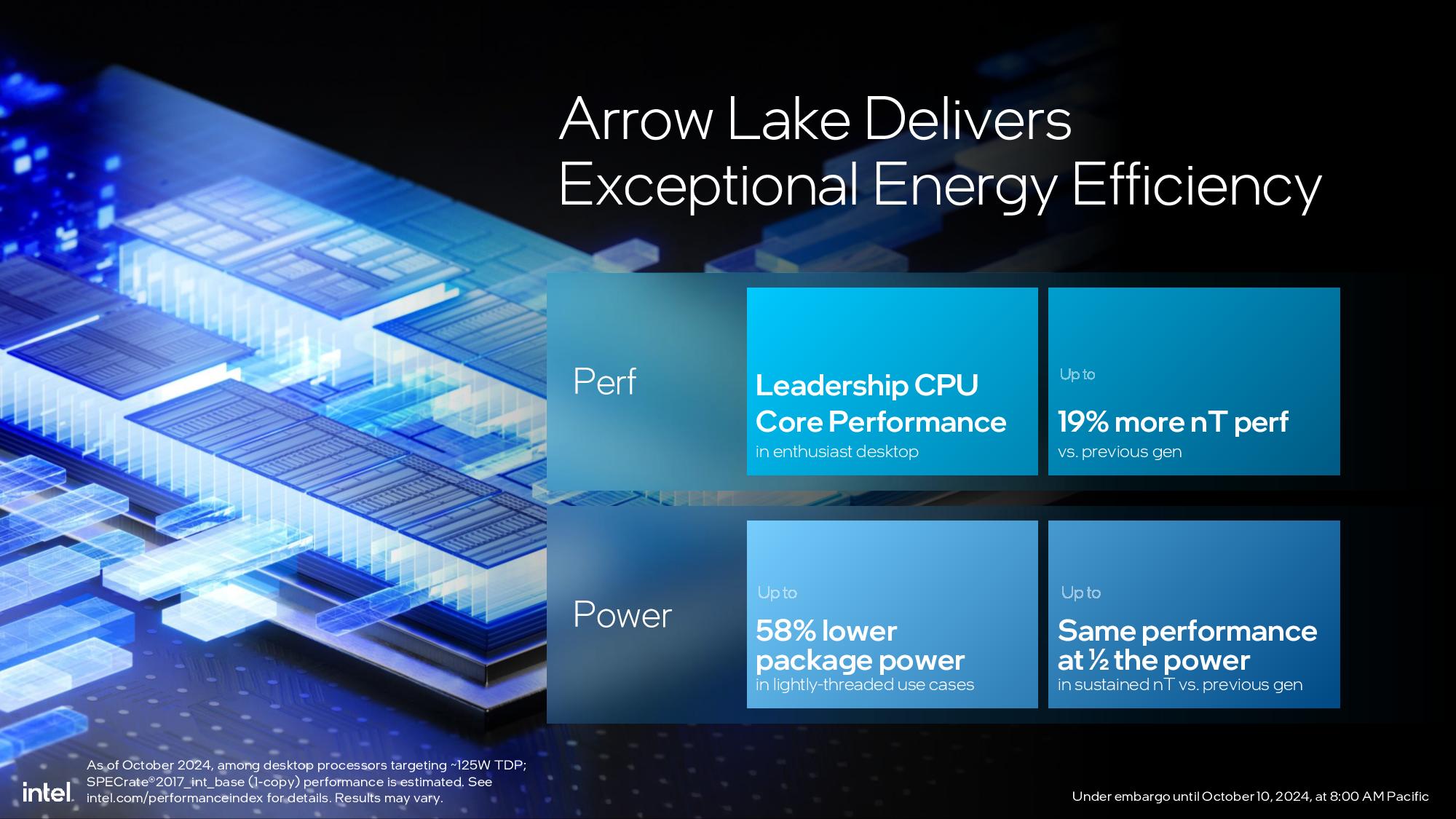

Overall, Intel claims the Core Ultra 9 285K lowers the CPU package power consumption by up to 58% in lightly-threaded workloads over the 14th-gen models. Intel used several productivity workloads to illustrate the lower package power consumption, but some of those benefits will also be applicable to games as well. Intel says it pairs the lower power consumption with up to 19% more performance in multi-threaded workloads, and can deliver the same level of performance at half the power consumption of the 14900K.

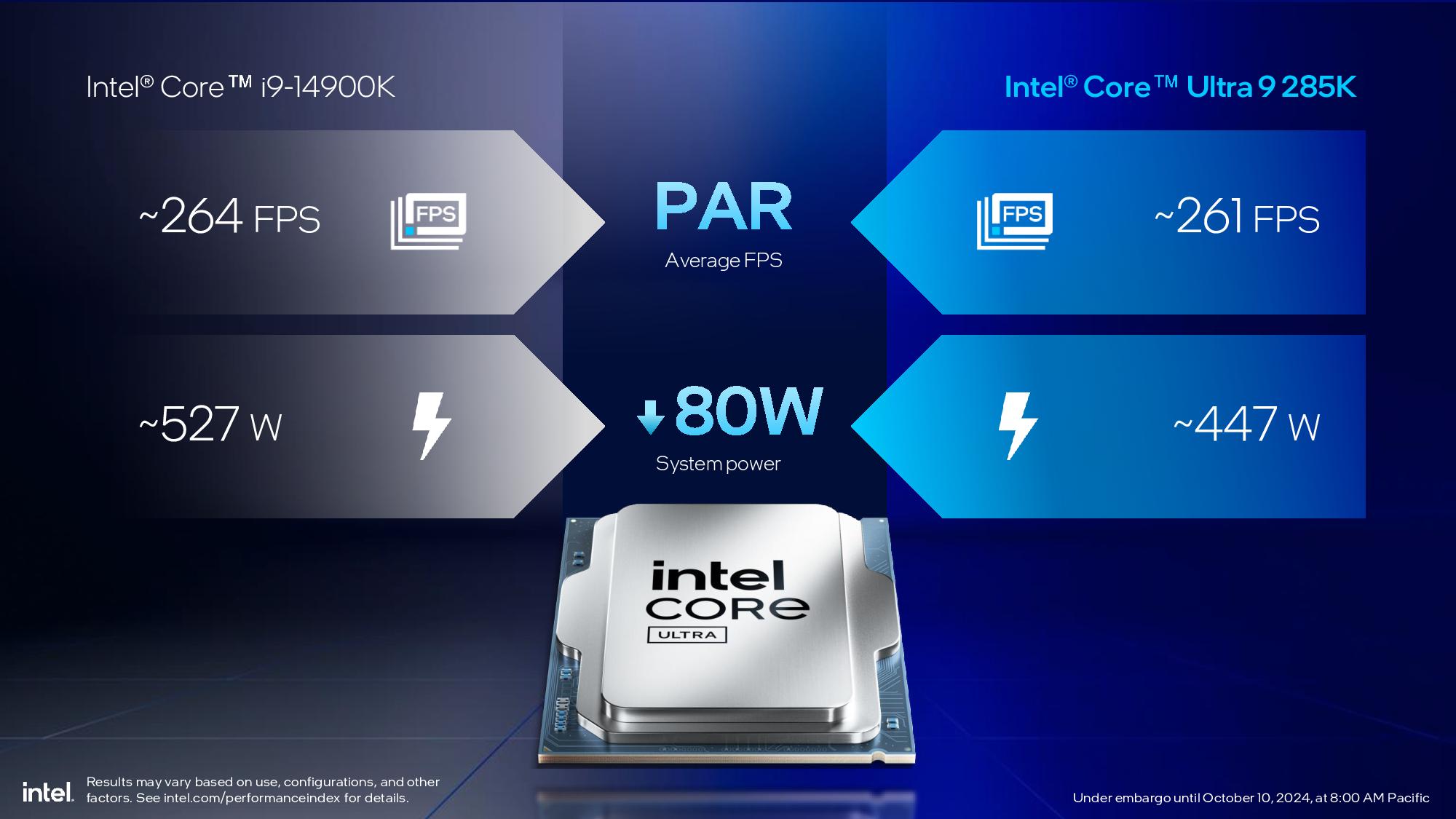

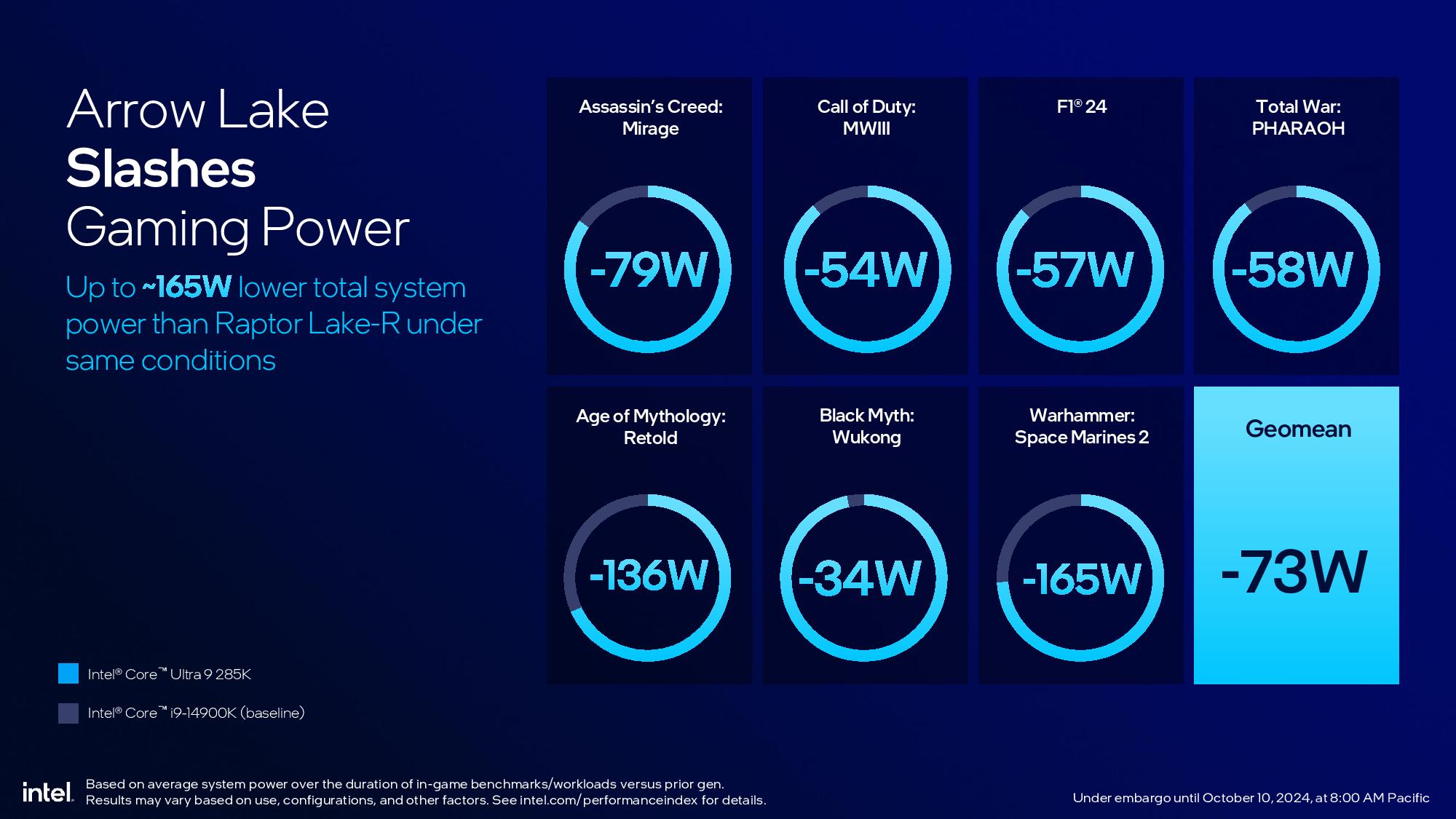

For gaming, Intel presented a range of games with the Ultra 9 285K compared to the 14900K, showing similar performance yet with drastically lower power consumption values when measured as a complete system. For the system power measurements, Intel used values from an entire system, comparing like-for-like with a prior-gen 14900K with a Z780 motherboard against Core Ultra 9 285K system with an 800-series motherboard, citing up to 165W less power consumption in Warhammer 40,000: Space Marine 2. Again, Intel’s performance claims of performance parity against the 9950X don’t entirely line up here, as the 14900K is roughly 10% faster than the 9950X, yet Intel shows the 285K matching the 14900K in these benchmarks.

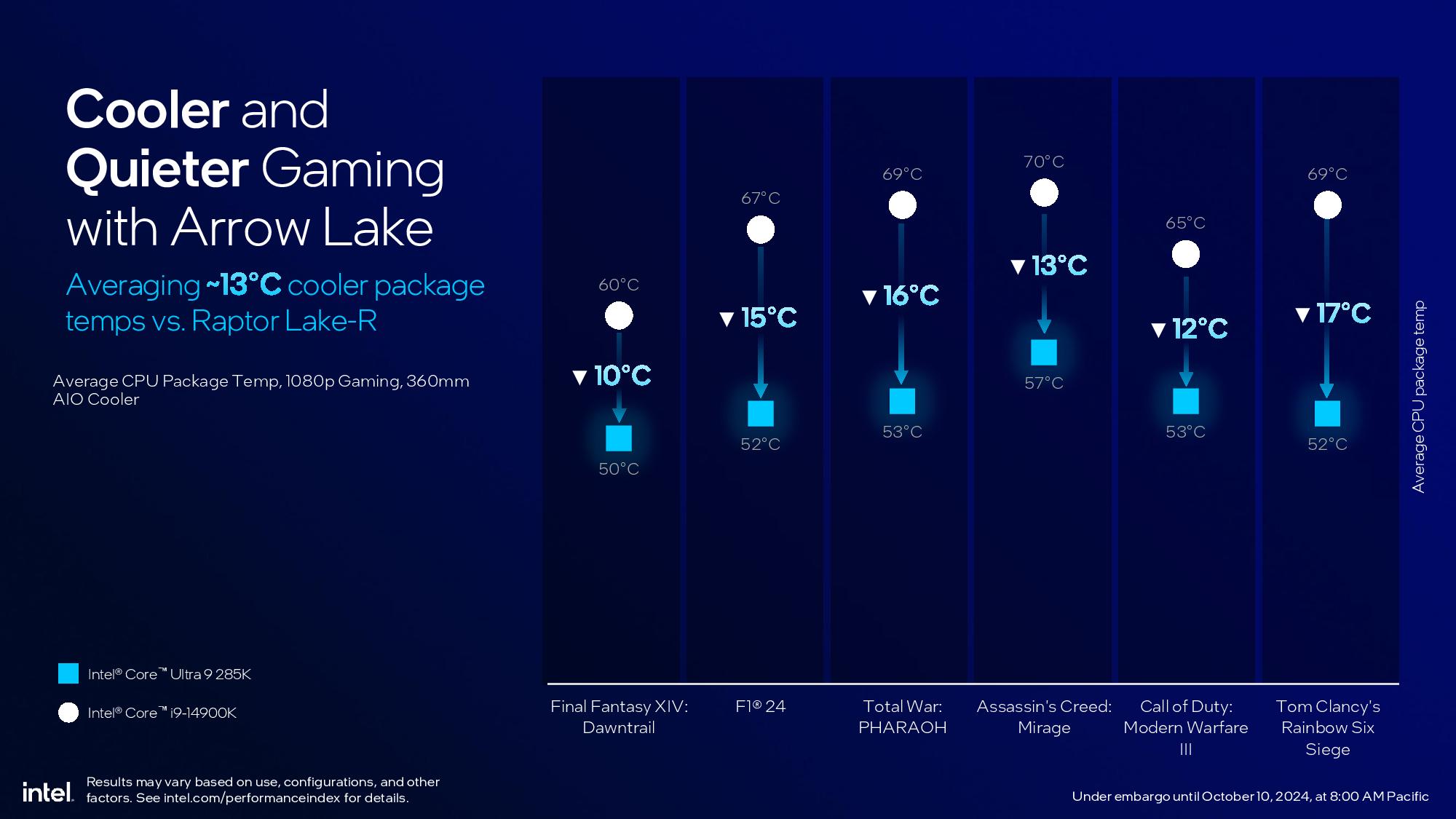

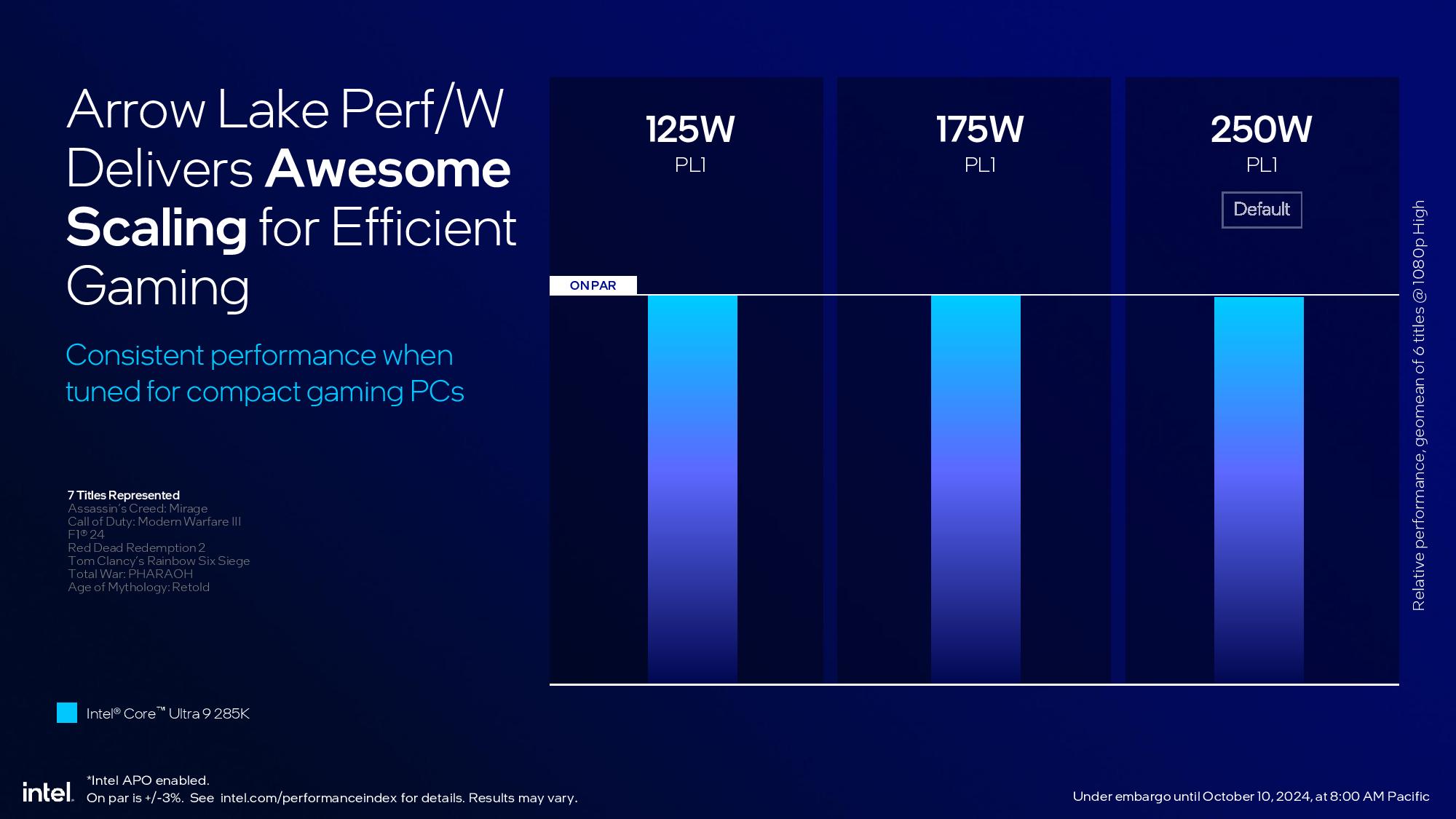

Across seven titles, Intel says the 285K delivers a geomean of 73W less power consumption than the 14900K. This correlates with up to 15C lower CPU package temperatures during gaming, which will then ease cooling requirements. The company also claims the Ultra 9 285K delivers the same gaming performance (across seven titles) at 125W as it does at 250W, but presented all of its other benchmarks with the 250W power limit.

Perhaps most importantly, Intel avoided gaming power consumption comparisons to AMD’s Zen 5 Ryzen 9000 lineup, which AMD also positions as being far more power efficient than the company’s Zen 4 products. For Intel to make power efficiency a convincing selling point it will have to show a tangible lead over the Ryzen processors. Intel did point to a power efficiency advantage over the Ryzen 9 9950X in multi-threaded productivity applications, but we’ll have to wait for independent benchmarks to see how the chips compare in gaming.

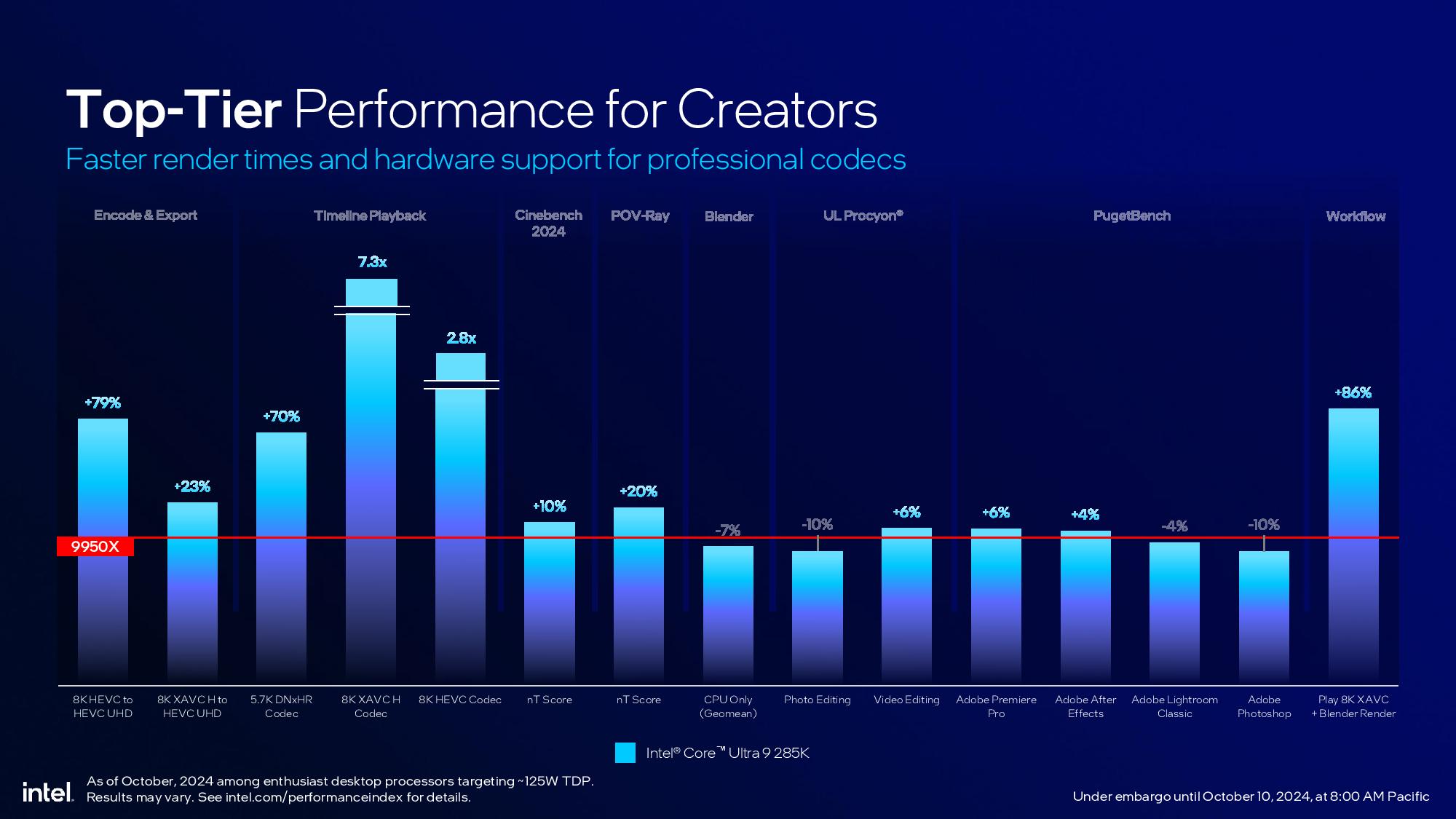

Intel Arrow Lake Core Ultra 200S productivity benchmarks

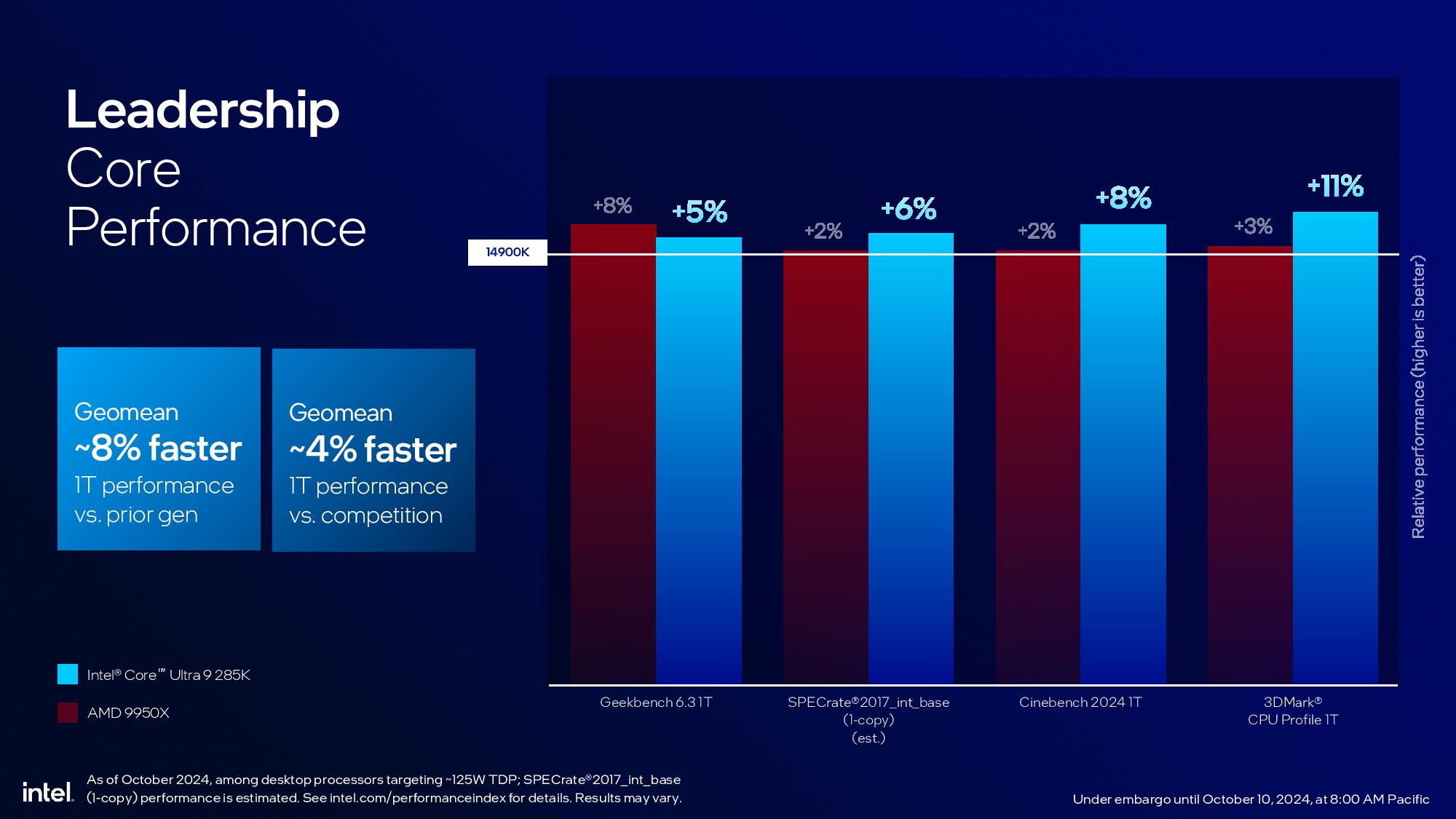

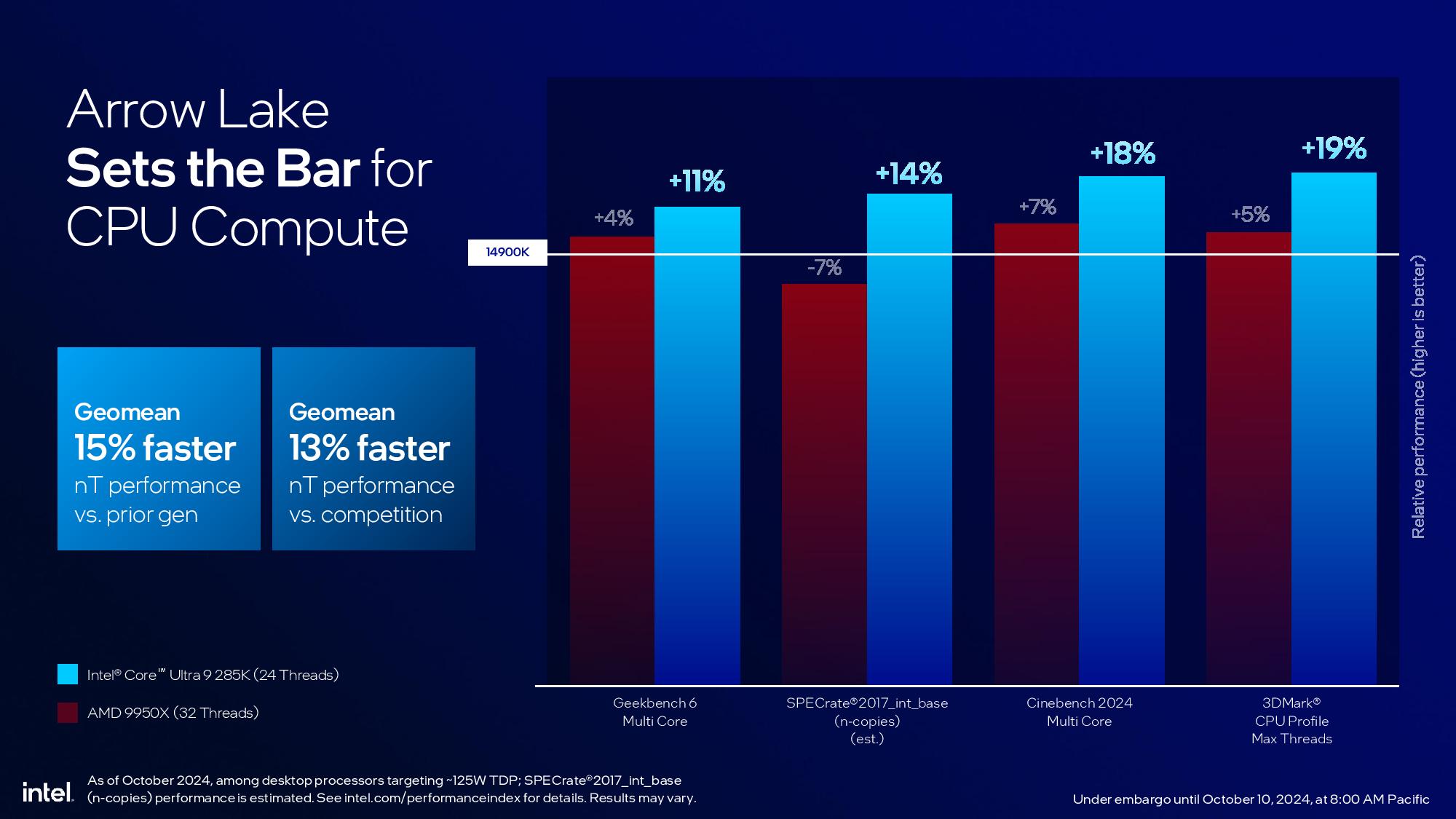

Intel was more forthcoming with productivity application benchmarks. As you can see across a wide range of benchmarks above, Intel highlights the 285K has faster performance in multi-threaded workloads than the 9950X, despite the fact that it removed Hyper-Threading from the Core Ultra series. If true, that means Intel provides more performance with 24 threads than Ryzen does with 32 threads. Overall, Intel claims a 15% gen-on-gen improvement in threaded work, and a 13% advantage over the 9950X.

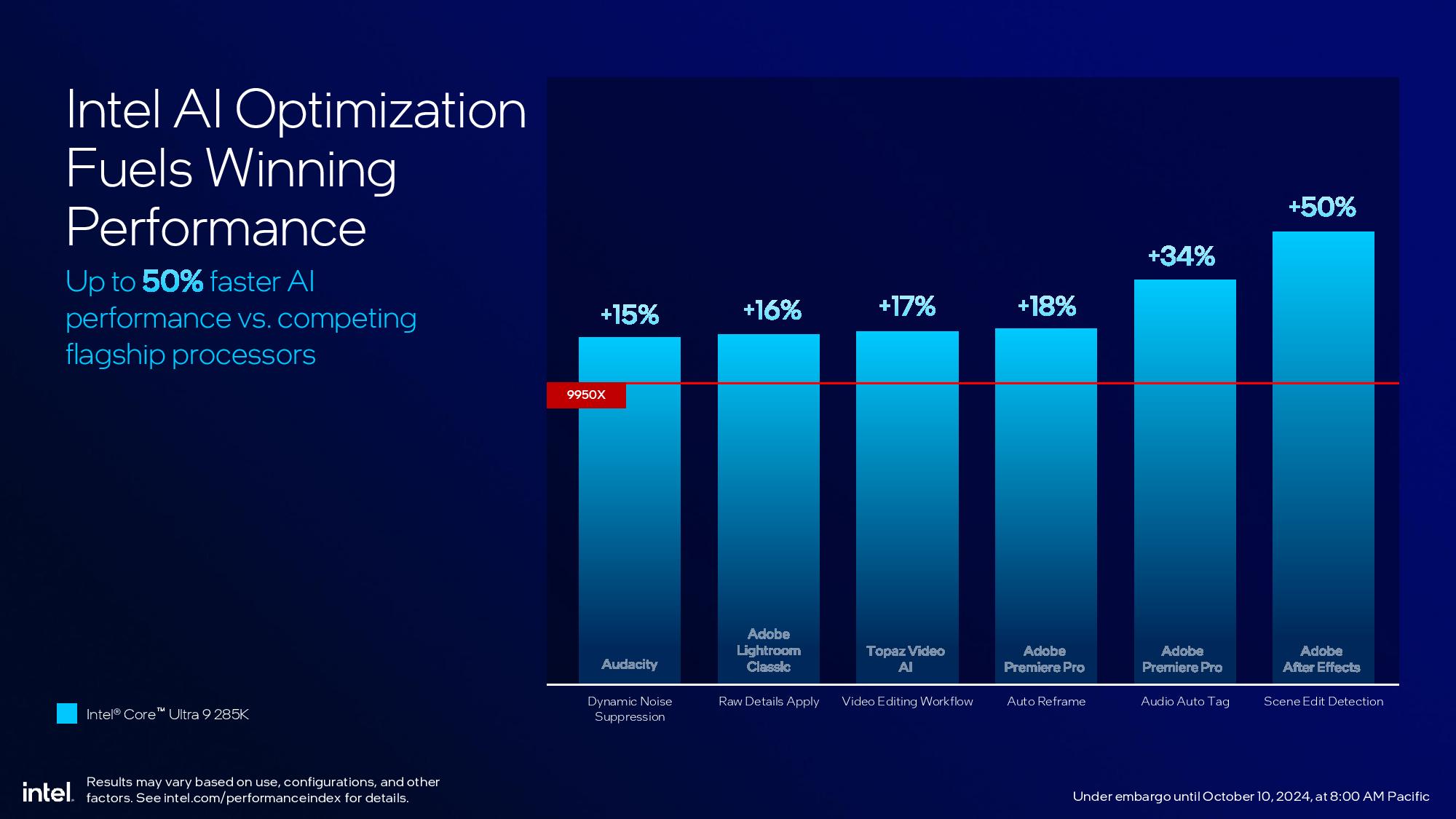

Intel also says the processor delivers up to 36 TOPS of total INT8 performance in AI workloads, with 8 TOPS from the GPU, 13 TOPS from the NPU, and 15 TOPS from the CPU. Notably, Intel chose the Xe-LPG graphics engine instead of the newer Battlemage architecture, so the iGPU supports DP4a and doesn’t come with the more performant XMX (matrix) engines.

Intel Arrow Lake Core Ultra 200S architecture

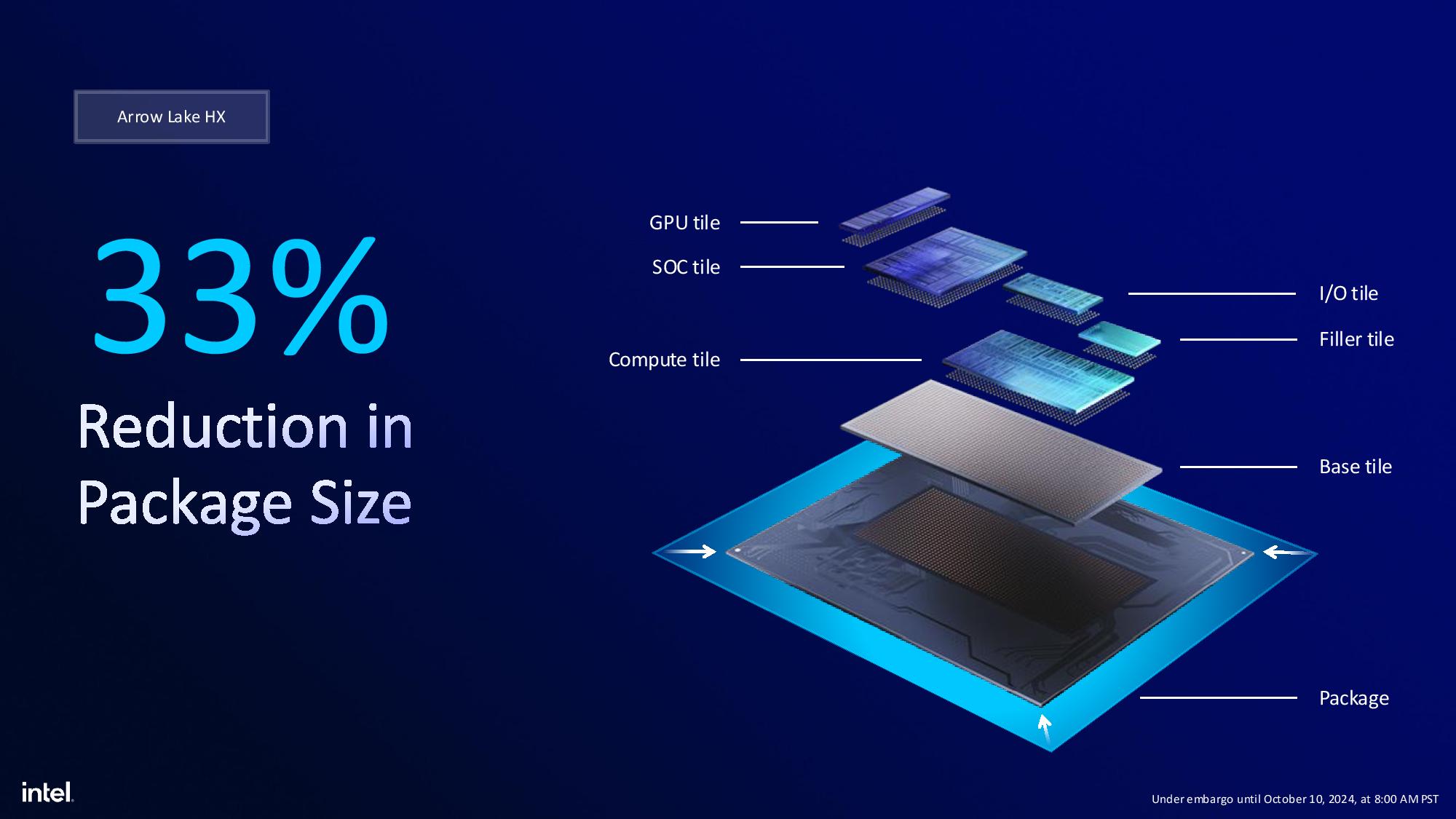

Intel used a very similar package design to its five-tile previous-gen Meteor Lake laptop processors instead of the newer Lunar Lake design. However, Intel roped in the newer Lion Cove P-core and Skymont E-core microarchitectures for the compute tile instead of the Redwood Cove and Crestmont cores used in Meteor Lake. The Arrow Lake design employs a compute tile (chiplet) fabbed on the TSMC N3B process node, a GPU tile with the N5P node, while the SoC and I/O tiles use TSMC’s N6 process. Intel uses Foveros 3D packaging to mount those tiles to an underlying base tile fabbed on the Intel 1227.1 process node (22nm FinFET). There’s also a ‘dummy’ filler tile to provide mechanical rigidity.

Intel’s decision to split the memory controller and PHY into their own tile (I/O tile) was to improve yields, but this creates memory latency issues that contribute to the lower gaming performance. Intel does offer the option to overclock the tile-to-tile interface, but we’ll have to see how that plays out in real-world testing.

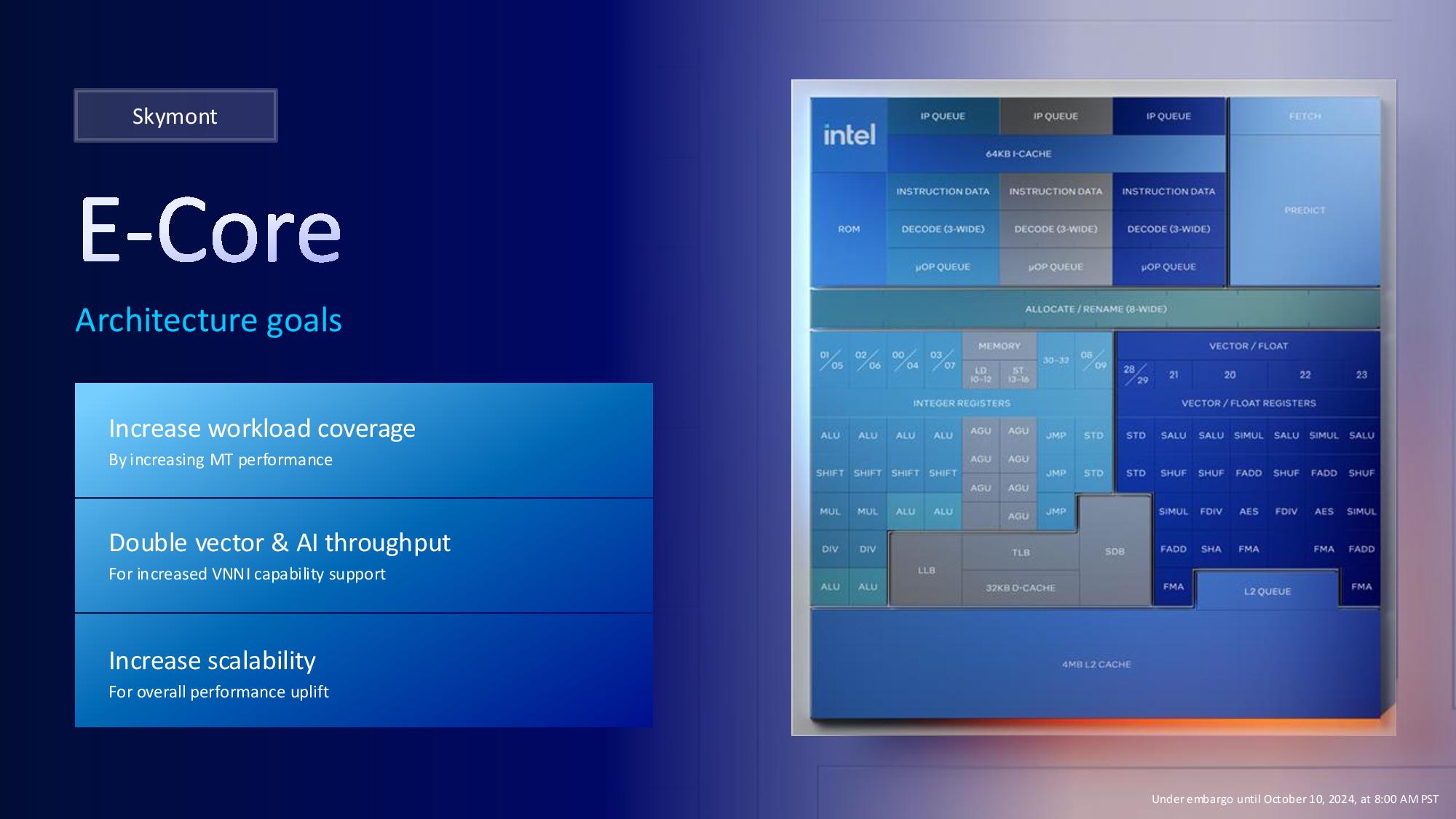

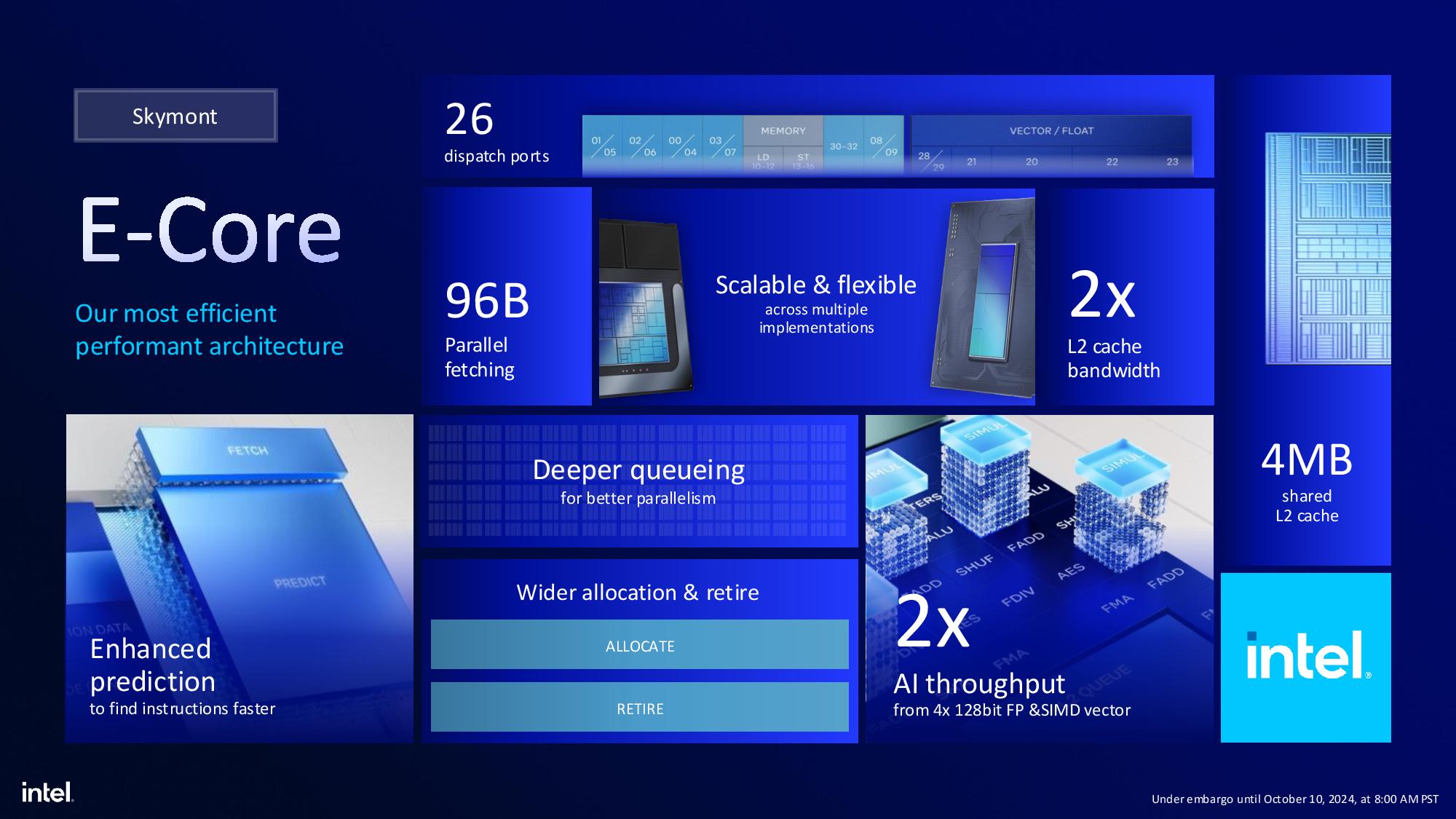

Intel also redesigned its core layout, which now has quad-core E-core clusters interspersed among the P-cores. Intel used to place all the E-cores in their own dedicated block, but says it spread the cores out to reduce hotspots for this design. Intel also connected the E-cores to the 36MB L3 cache, so they now share L3 with the P-cores for the first time. The P-cores and E-cores still have their own dedicated L2 caches, with 3MB for the P-cores (a .5MB increase over the prior gen), and 4MB of L2 shared among each E-core cluster. Intel says the totality of the new design yielded a 33% reduction in package size and said the design allowed it to quickly port innovations from Lunar Lake to Arrow, thus resulting in launching the two chips a mere month apart.

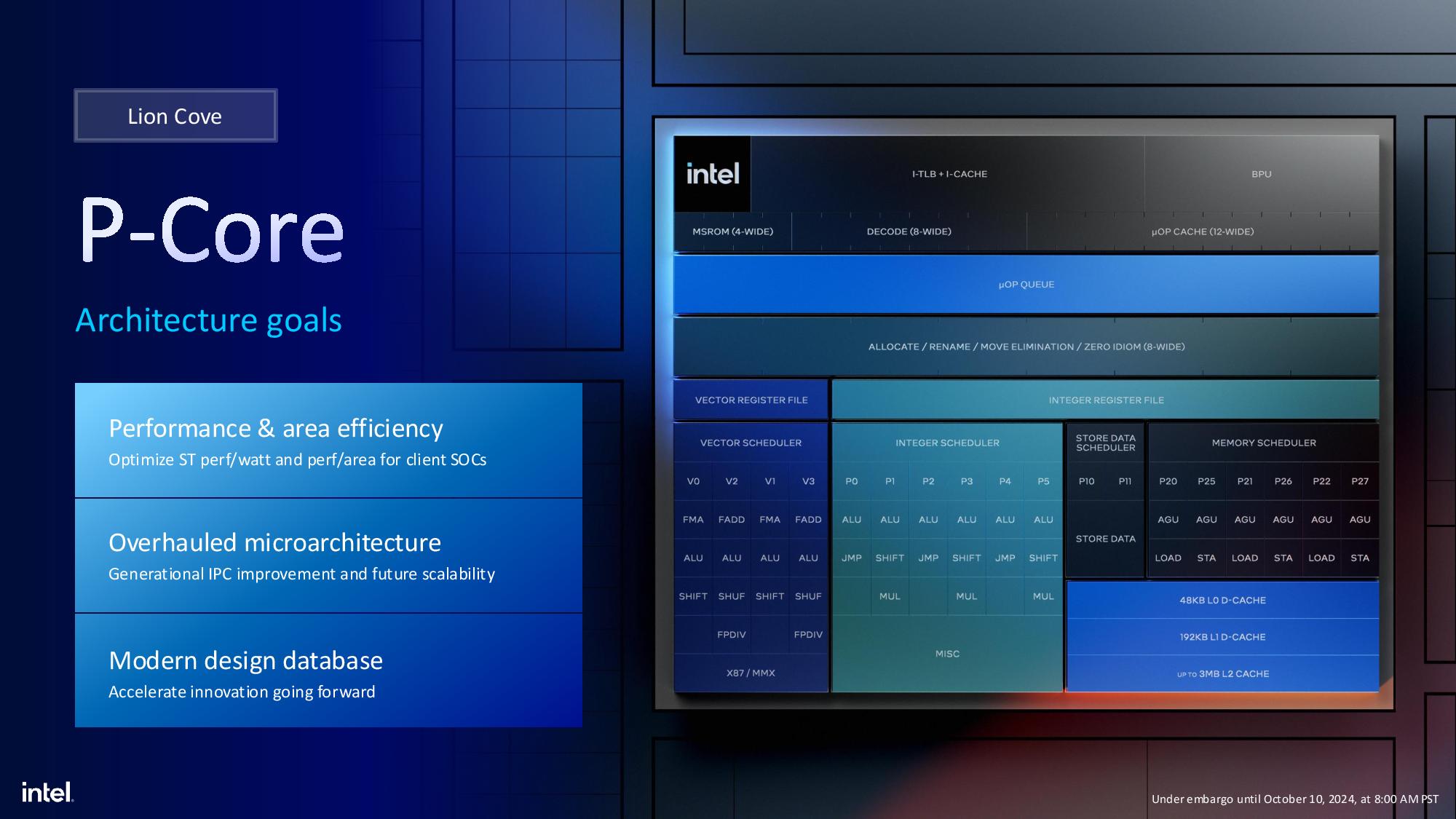

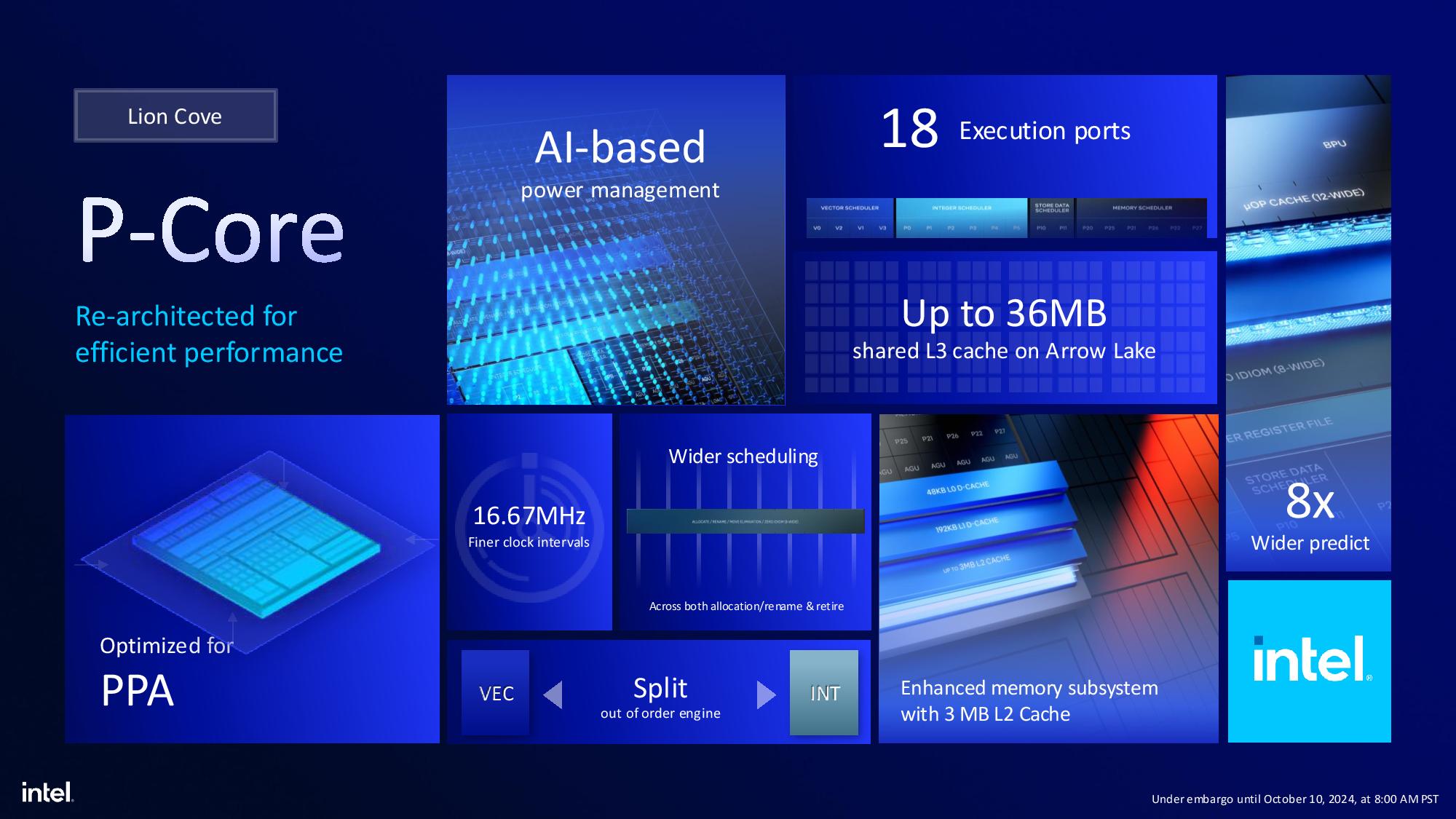

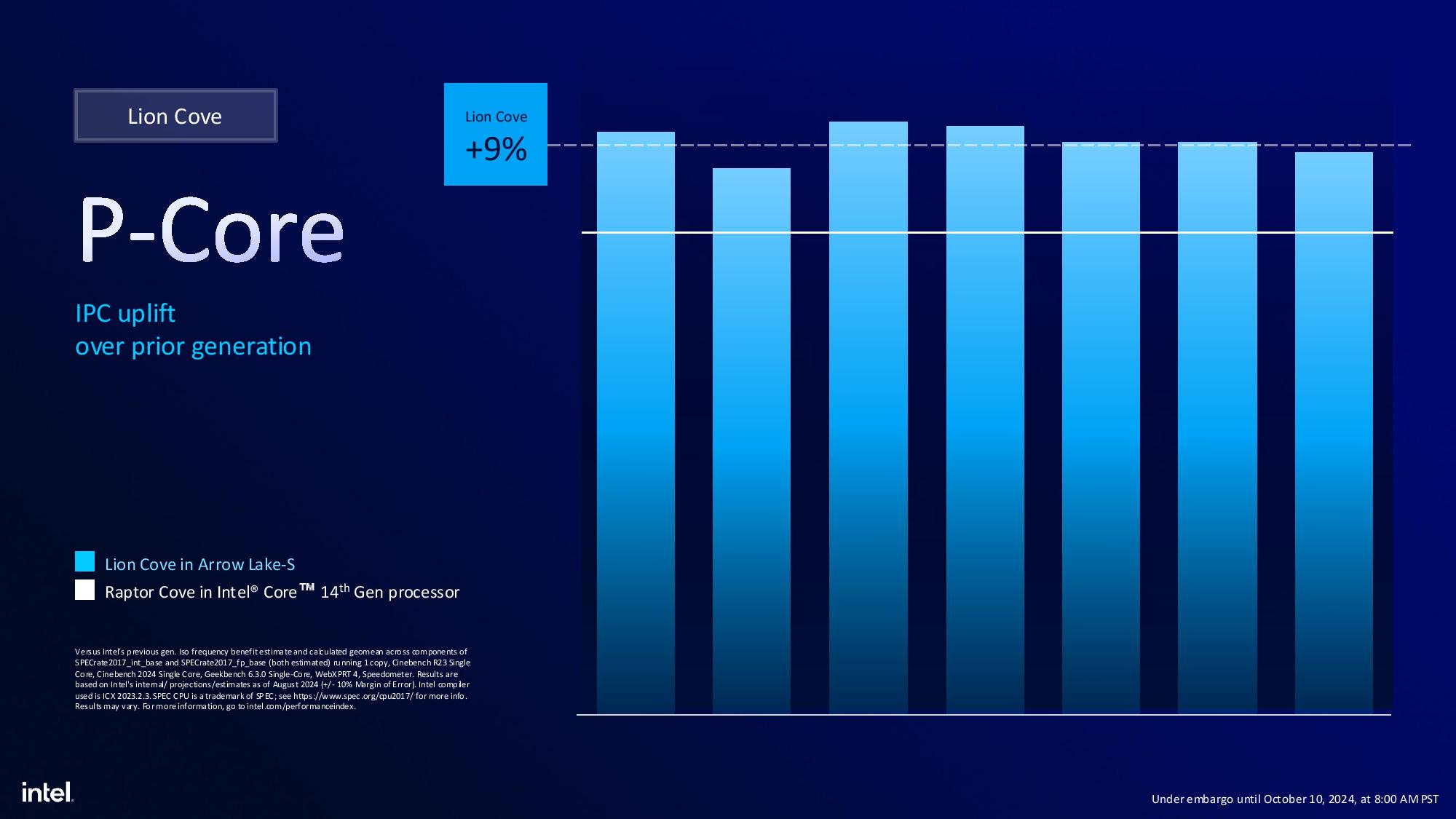

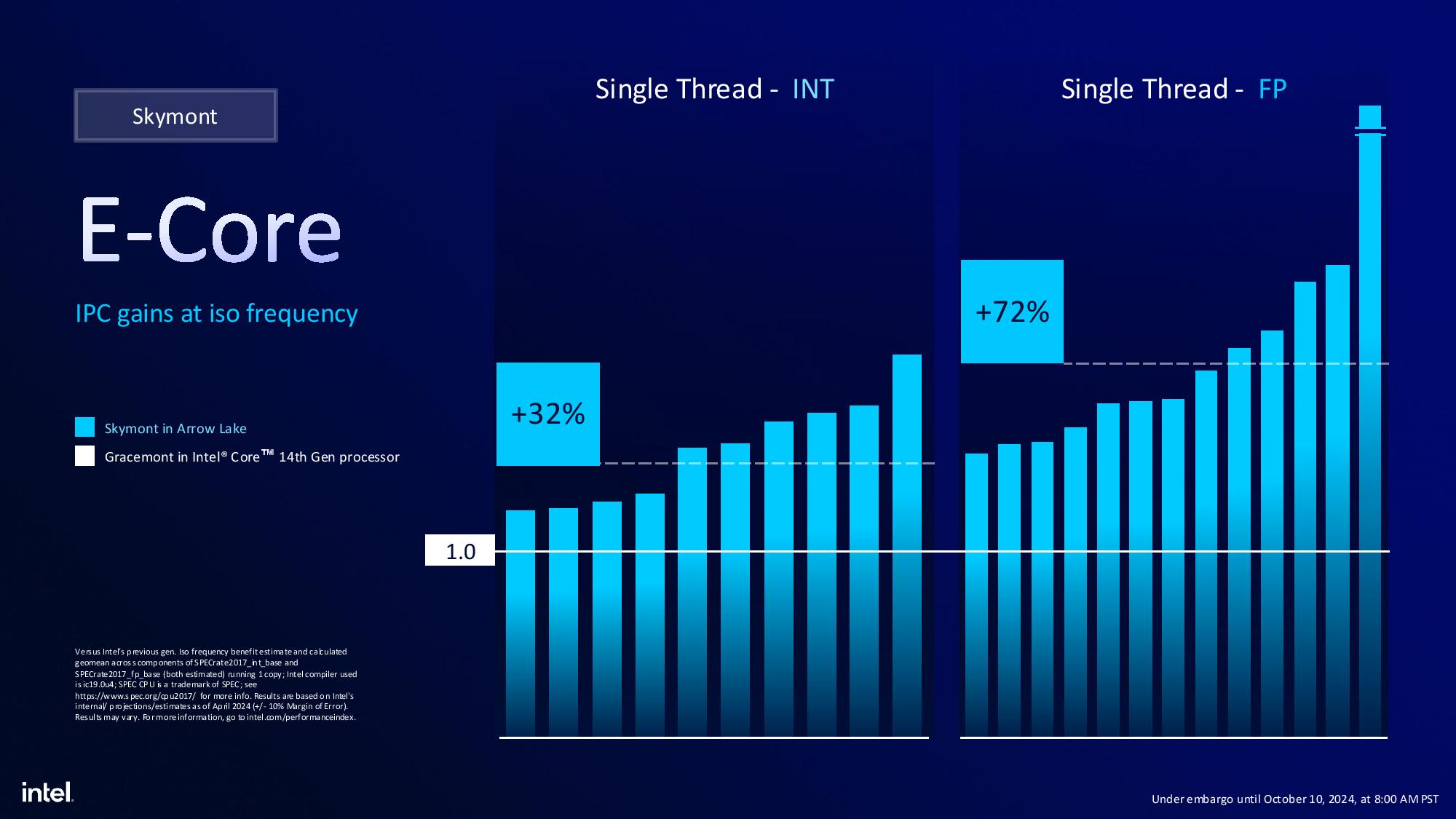

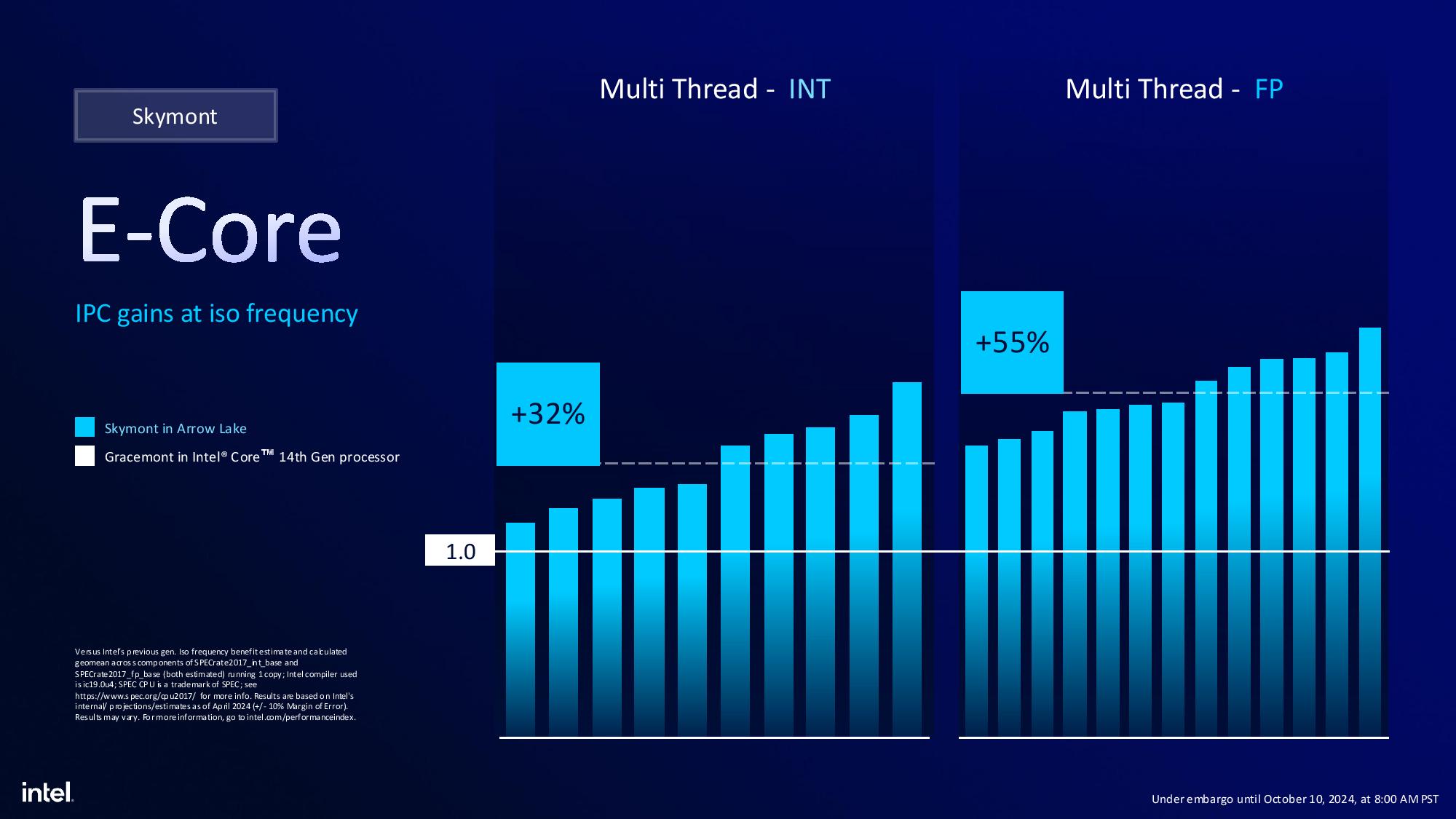

We’ve included the slides detailing the advances of the P-core and E-core architectures, but we’ve already covered these microarchitectures in-depth in our Lunar Lake deep dive. Overall, we’re looking at a 9% increase in IPC over Raptor Lake (lower than the 14% cited with Lunar Lake because Intel did that comparison to Meteor Lake), a 32% increase in integer IPC, and a 72% increase in floating point IPC for the E-cores.

Intel Arrow Lake Core Ultra 200S overclocking and 800-series chipsets

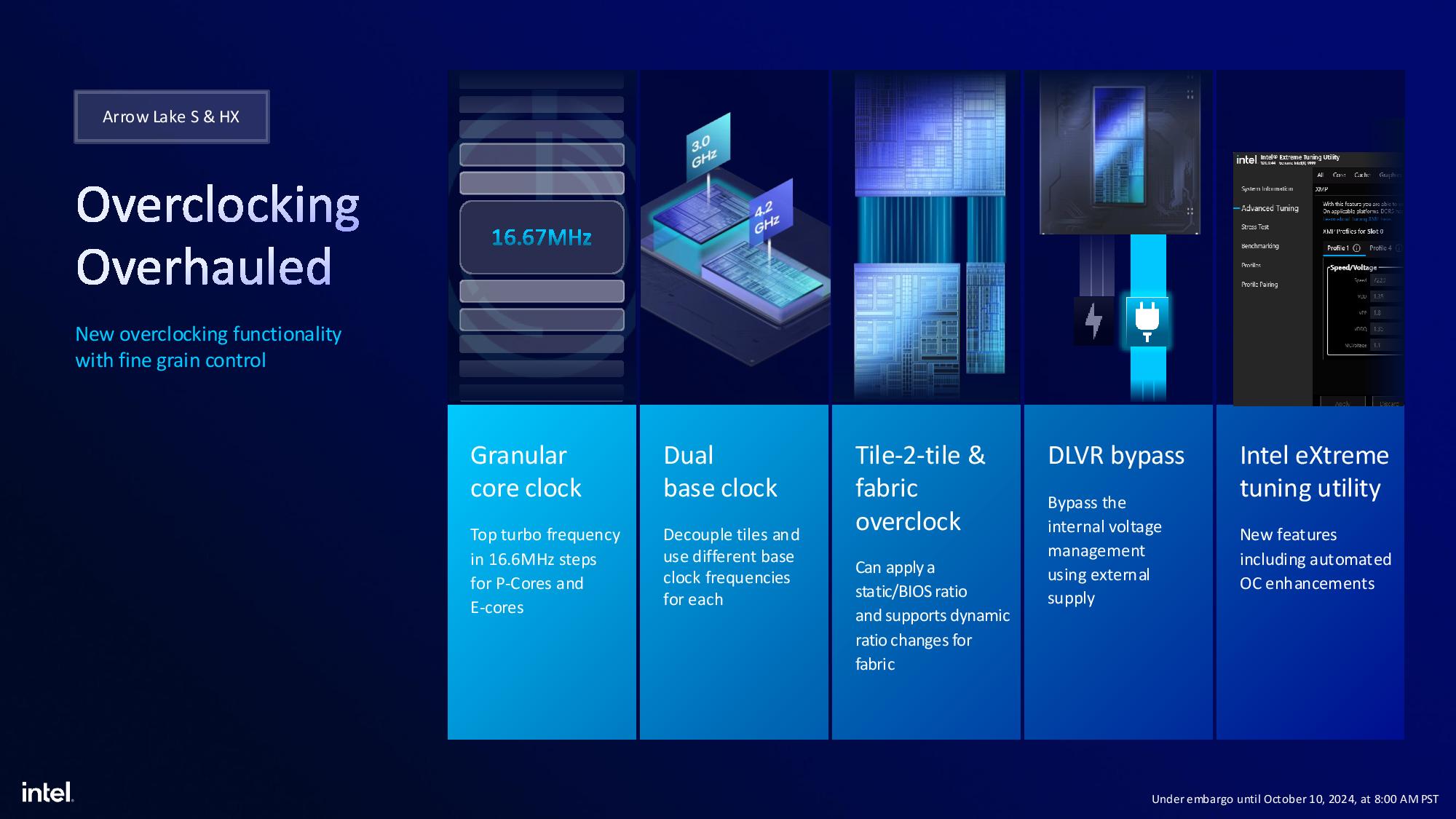

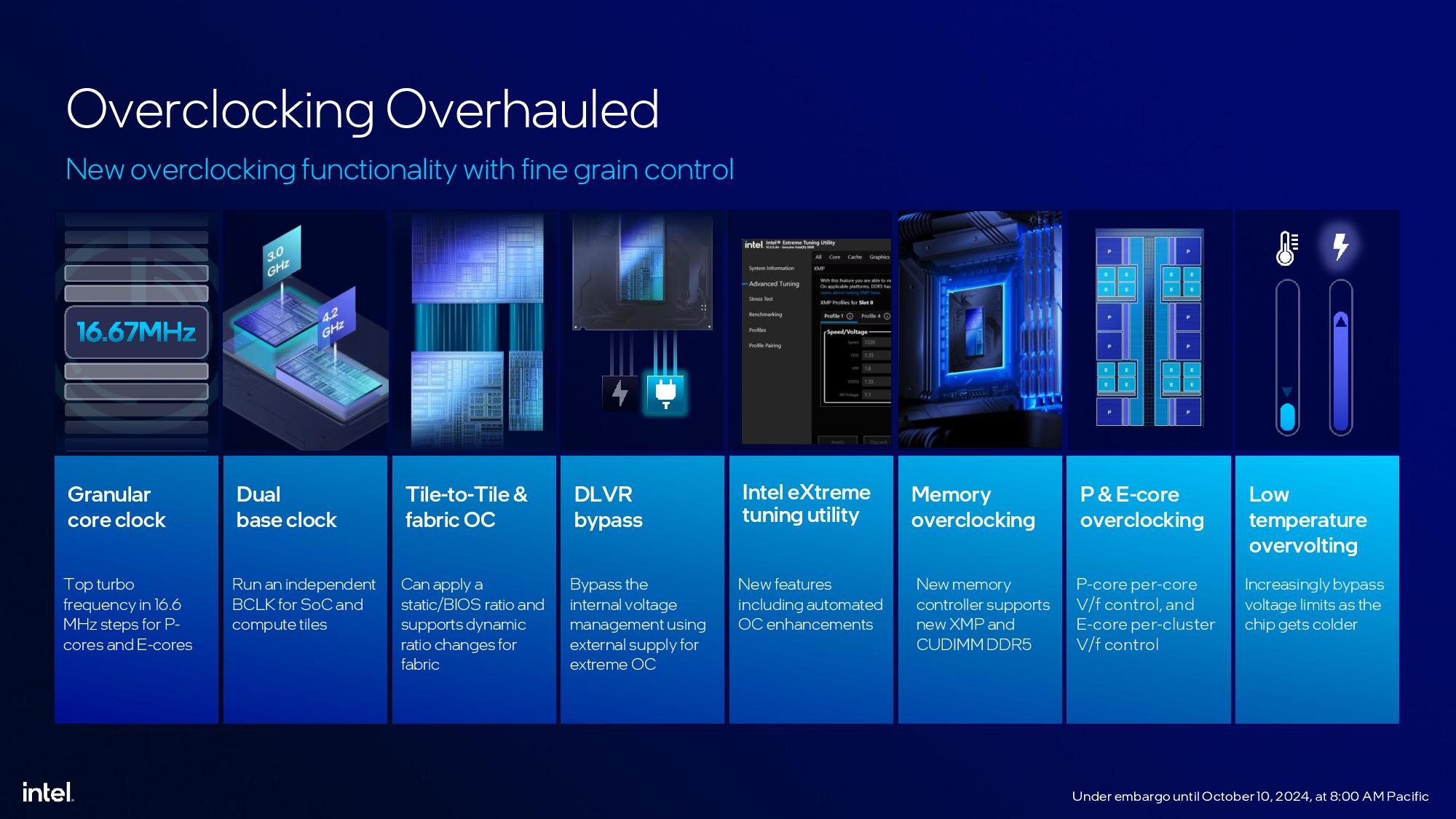

Finally, we have details on the 800-series chipsets and overclocking. The tile-based architecture brings several new overclocking features, such as the ability to overclock the tile-to-tile interface, which could help at least partially address memory latency issues that stem from the remote I/O tile. Intel increased clock granularity and now allows increasing or decreasing the clock rate in 16.6 MHz increments.

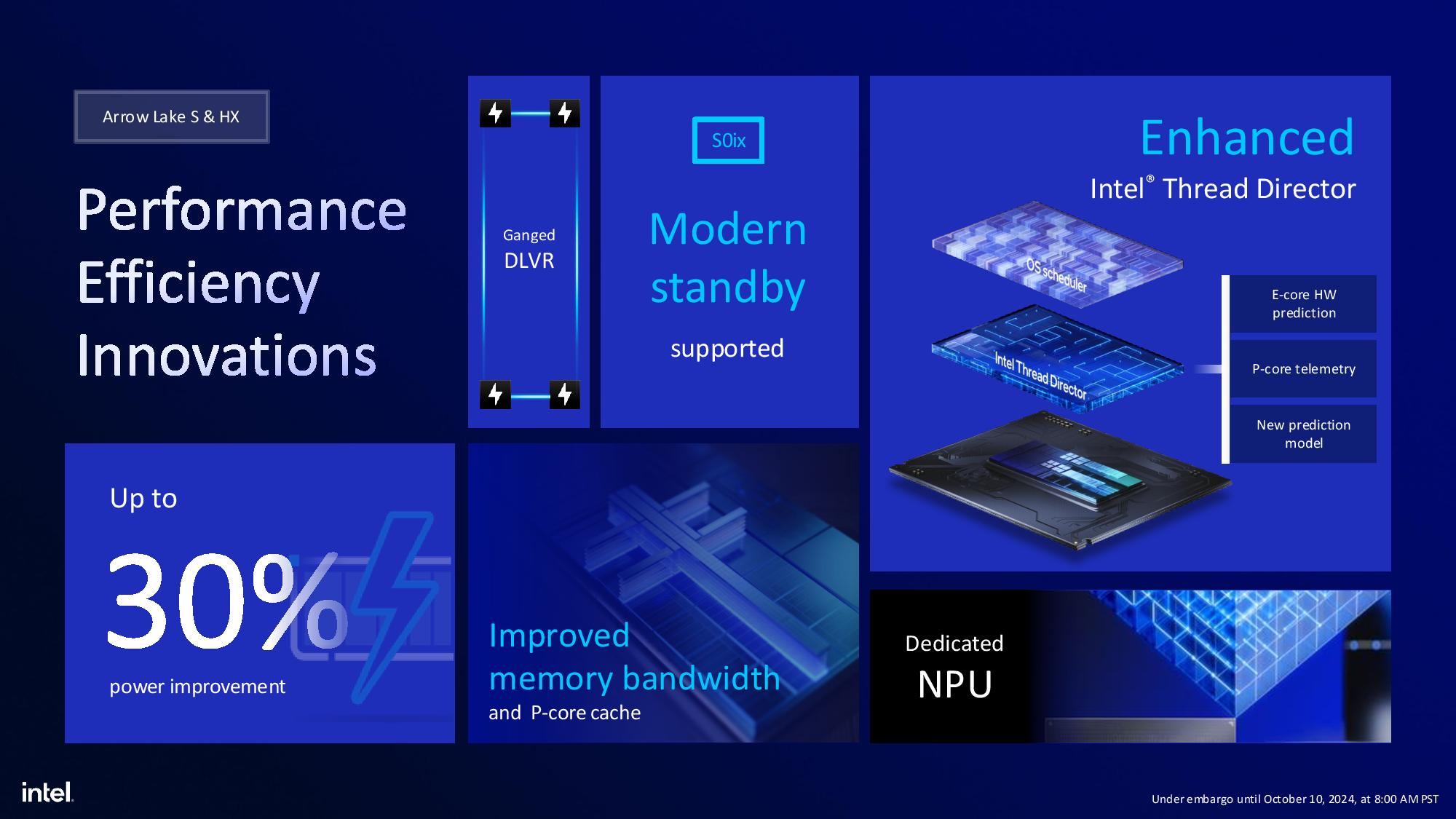

Arrow Lake also has two adjustable base clocks due to the tiled architecture. The compute tile and SoC tile each have their own adjustable base clock. Intel employs a DLVR power delivery subsystem for the processor to provide granular per-core control of voltage, but overclockers can disable this feature to improve overclockability.

On the topic of core overclocking, Intel says that the P-cores will not have much frequency headroom — the chip is designed to expose peak performance with the out of box settings. However, the E-cores should have more headroom for tuners. Intel also has a one-click AI-driven overclocking feature in XTU, just as it has had in the past.

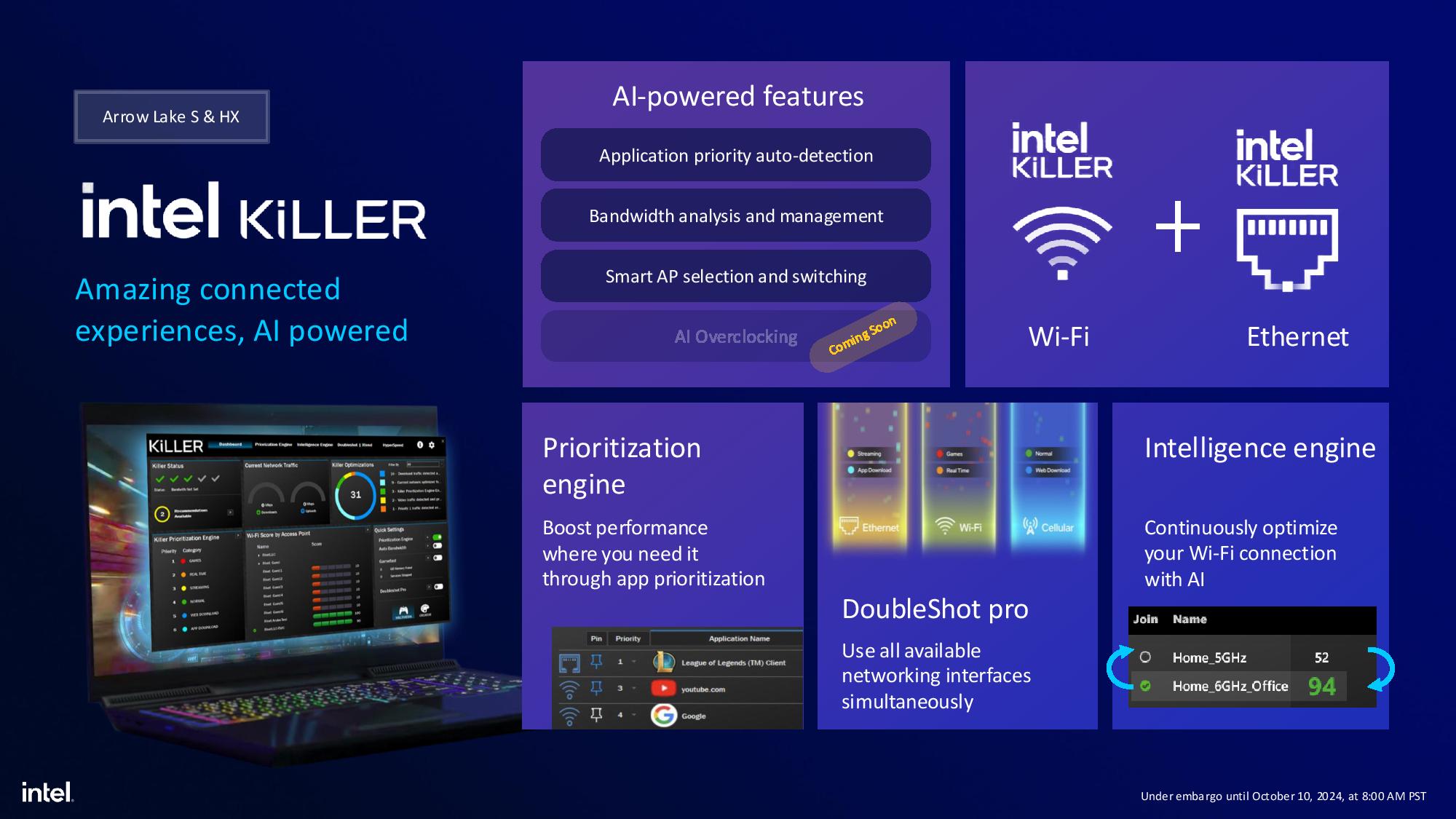

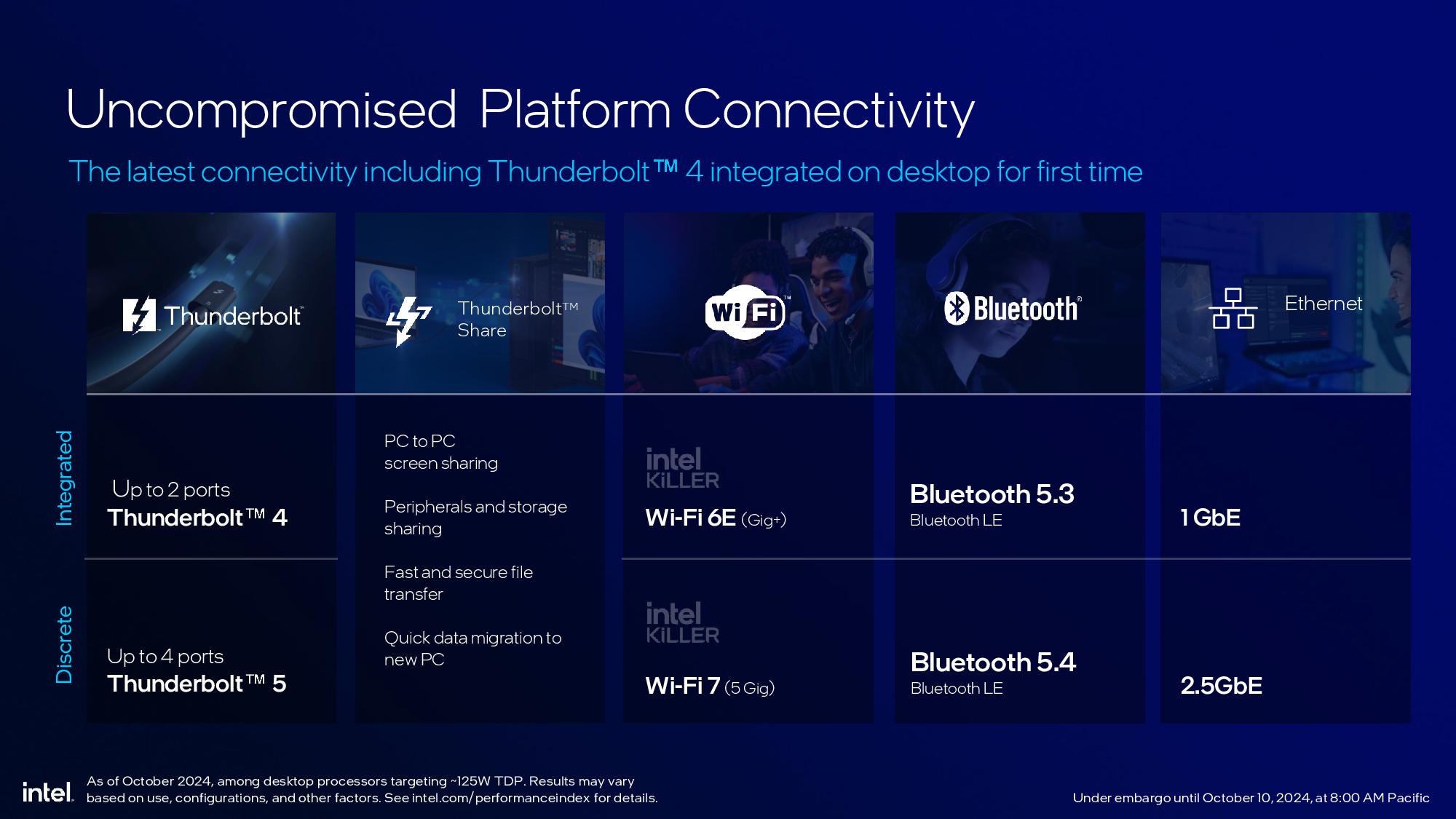

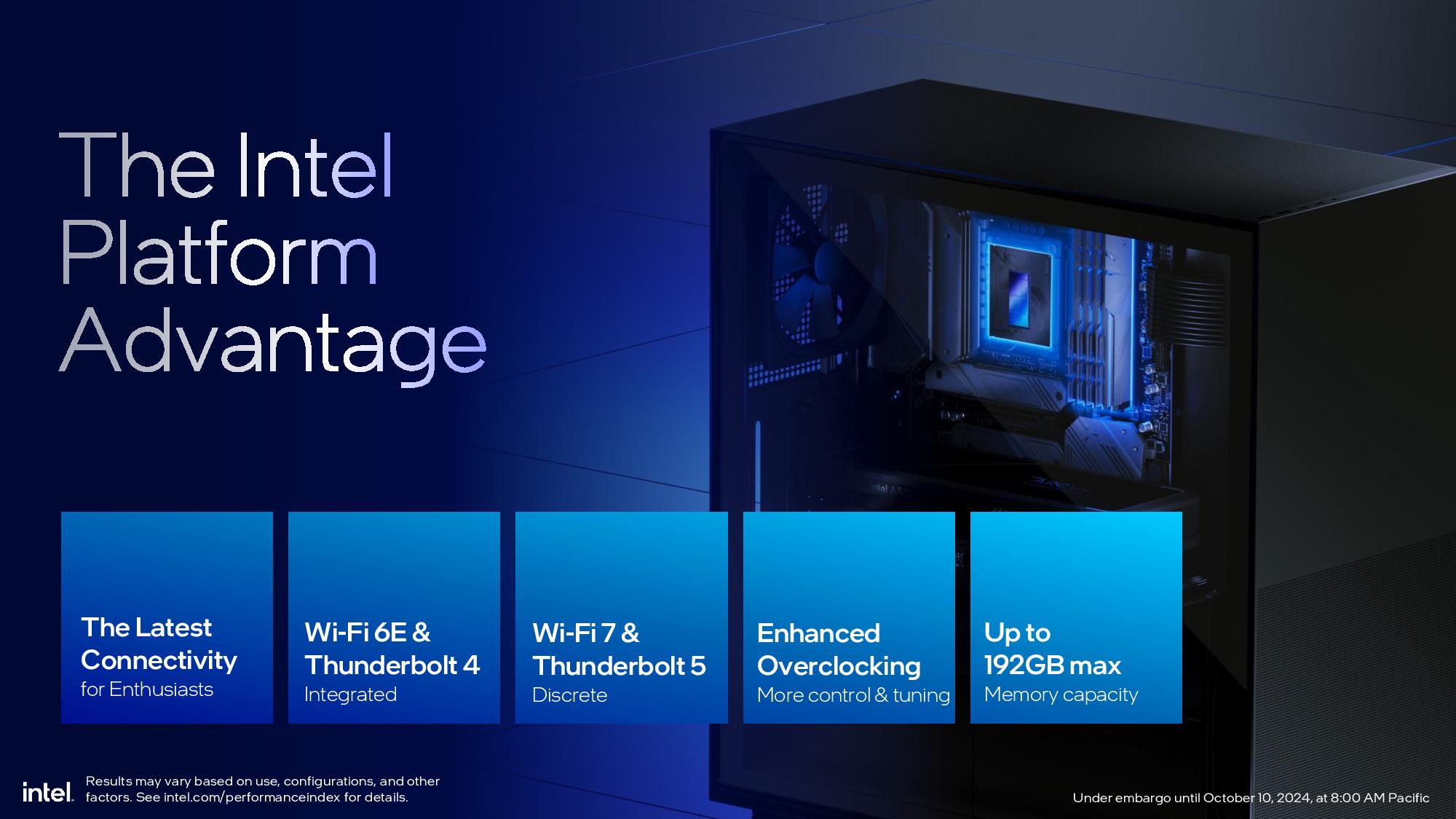

The 800-series is largely a refresh from the 700-series chipset. The chipset provides 24 PCIe 4.0 lanes, a robust complement of USB interfaces, Thunderbolt 4, 1GbE, along with built-in Wi-Fi 6E and Bluetooth 5.3. Support for Thunderbolt 5, Wi-Fi 7, 2.5 GbE, and Bluetooth 5.4 will come from discrete chips on selected motherboards.

Thoughts

Intel’s gaming benchmarks are somewhat questionable, especially in regard to whether or not the Arrow Lake processors are faster than Intel’s own current-gen models. Given those disparities, it’s also hard to determine the relative positioning compared to AMD’s Ryzen 9000 series — it’s possible the Ryzen 9 model is faster than intel’s flagship, if only by a small margin. That could breathe new life into AMD’s Zen 5 lineup, but it could also mean that Intel’s current-gen Raptor Lake Refresh chips might remain the chips to buy for gamers for quite some time.

Intel makes the case that drastically improved power consumption in gaming will be a big draw for enthusiasts. We’re skeptical, and we’ll have to see how Arrow Lake compares to Ryzen 9000. Intel avoided those comparisons, but we’ll be sure to provide the insight with our review.

Intel does appear to have made inroads in performance in productivity applications, and that will definitely attract the more productivity-minded among us. As always, the proof will be in the shipping silicon. If tradition holds, reviews will go live on October 24.