The search for habitability elsewhere in the universe can arguably be reduced to the search for water. We haven’t yet found lifeforms that detach this substance from our conception of “life” itself, so we have no choice but to accept the cosmic water trail as our north star in the quest to find worlds that mirror our own.

It is for this reason that scientists jump for joy a little when they find an exoplanet likely to hold any water at all — but particularly liquid water, rather than ice or water vapor. And I’d hope at least one astronomer gleefully hopped somewhere recently, as a team of researchers just announced that a tantalizing planet outside the solar system may have a temperate water ocean about half the size of the Atlantic. Better yet, the find is thanks to the James Webb Space Telescope.

“Of all currently known temperate exoplanets, LHS 1140 b could well be our best bet to one day indirectly confirm liquid water on the surface of an alien world beyond our solar system,” Charles Cadieux, lead author of a paper on the discovery and a doctoral student at the Université de Montréal, said in a statement. “This would be a major milestone in the search for potentially habitable exoplanets.”

Dubbed LHS 1140 b, the exoplanet orbits a red dwarf star about a fifth the size of the sun and sits 48 light-years away from Earth in the constellation Cetus which, as luck would have it, translates to “the whale.” But most important about LHS 1140 b is the fact that it lives in its star’s habitable zone, otherwise known as its “Goldilocks zone.” As that nickname would suggest, this is the area around a star where it’s neither too hot nor too cold for a world to host liquid water, but rather fits the standard by which the fairy tale character Goldilocks lives. There’s also a second major win for the world.

Related: Nearby exoplanet may be rich in life-giving water, study finds

“This is the first time we have ever seen a hint of an atmosphere on a habitable zone rocky or ice-rich exoplanet,” Ryan MacDonald, a NASA Sagan Fellow in the University of Michigan’s Department of Astronomy, who aided the analysis of LHS 1140 b’s atmosphere, said in the statement. Per Macdonald, the team might have even found evidence of “air” on it.

To the former bit of that statement, however, you may notice MacDonald suggests the exoplanet could be either rocky or icy. This brings us to some backstory.

LHS 1140 b lore

Though it has been making headlines now due to the new study involving JWST data, LHS 1140 b has actually been on planetary hunters’ radars for some time. In fact, experts had already theorized that this could be a water world in the past, and even shared similar sentiments about how it could offer humanity the first-ever direct evidence of exoplanetary liquid water. None of that is new. Cadieux himself has touted the world’s promise previously, and an army of telescopes has investigated it in solid detail, including the now-retired Spitzer telescope, the Hubble Space Telescope and the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS).

However, there was something missing until now: the James Webb Space Telescope’s keen eye.

It was necessary because, for a long time, there was something like a gap in the literature about LHS 1140 b. Basically, the trouble was that scientists couldn’t quite confirm whether the exoplanet is a mini-Neptune — a planet less massive than our original Neptune, but one that still has Neptunian characteristics — or a super Earth. A super Earth is a world that’s larger than Earth, but still either rocky or water-rich. The latter typically sounds the “potential habitability” alarm, and the JWST, scientists had imagined, could be the one to set it off.

This appears to have been an accurate inference. As the team’s statement on the study suggests, their work not only “strongly excluded” the mini-Neptune scenario, but also confirmed the world may have a nitrogen-laced atmosphere like Earth does. “While it is still only a tentative result, the presence of a nitrogen-rich atmosphere would suggest the planet has retained a substantial atmosphere, creating conditions that might support liquid water,” it says.

It is certainly worth noting that LHS 1140 b isn’t exactly fully alone in its exhilarating characteristics; there are also a variety of other habitable-zone exoplanets scientists are drawn to. The most obvious are probably the seven worlds of the TRAPPIST-1 system, a planetary lineup that looks almost disturbingly similar to our solar system’s structure. The septet of orbs resembles our octet (bye, Pluto) and some of them are in the habitable zone like Earth is.

However, a very interesting JWST study actually complicated the search for habitability in TRAPPIST-1 quite recently. It revealed that the system’s anchor star is incredibly active in such a way that it could skew our observations, making us believe a world in the system is habitable when it really isn’t. Even the JWST has its limitations. So, to that end, LHS 1140 b does have a few special embellishments.

“The star LHS 1140 appears to be calmer and less active,” Macdonald assured, “making it significantly less challenging to disentangle LHS 1140 b’s atmosphere from stellar signals caused by starspots.”

Brace yourself for even more specs

The excitement about LHS 1140 b is pretty contagious. There’s so much to say about it.

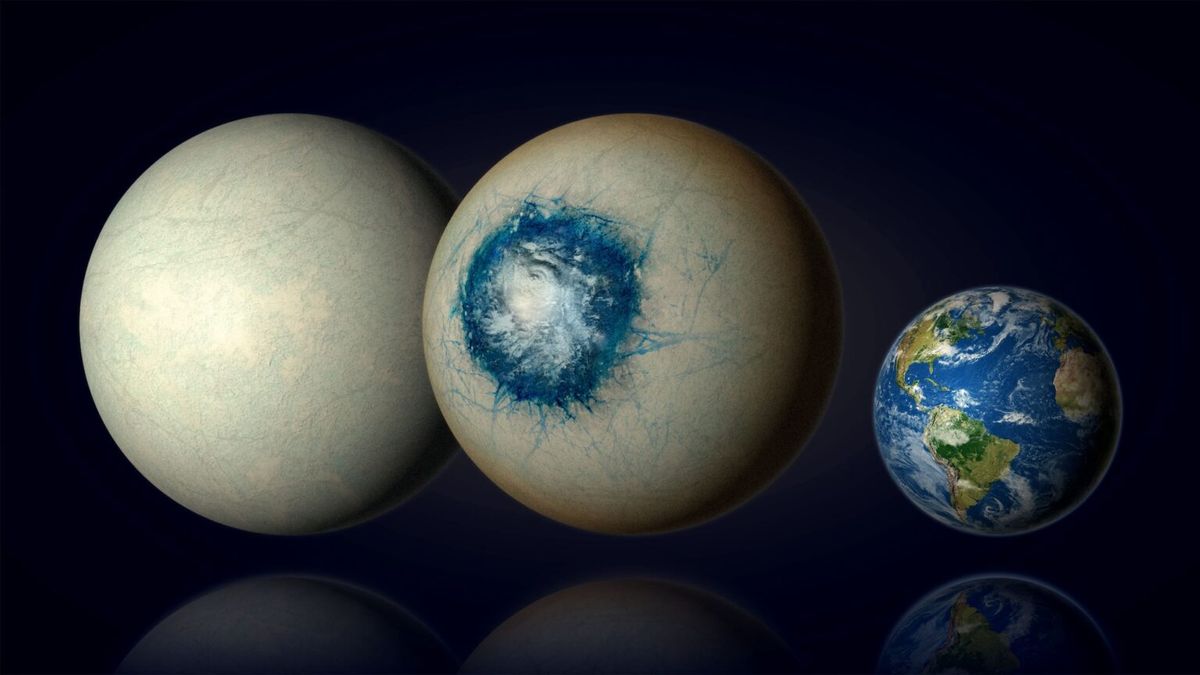

For example, the JWST data further suggests the exoplanet’s mass might be made of between 10 percent and 20 percent liquid water — and, it paints a fantastical picture of what the planet might look like in simple terms. It could look like a snowball, essentially, that orbits its star while rotating in such a way that one side always faces that star. It’s kind of like the moon’s orbit around Earth; we can’t ever see the far side of the moon because the moon rotates at the same rate it revolves around Earth. One side never faces us, and the other always does.

Similarly, this would mean that, if the JWST’s illustration of the LHS 1140 b scene is correct, the side of the planet always facing its sun would be exposed to lots of heat. This would be the part of the snowball that’s “melted” into a liquid ocean.

Voila.

“Current models indicate that if LHS 1140 b has an Earth-like atmosphere, it would be a snowball planet with a bull’s-eye ocean about 4,000 kilometers [2,485 miles] in diameter,” the statement says, adding that the surface temperature of the ocean may very well even be a “comfortable” 20 degrees Celsius (68 degrees Fahrenheit).

Alas, though the team assures that far more work must be done, especially with the JWST, in observing the nuances of LHS 1140 b — it is always nice to have a lead to follow when searching for needles in a vast haystack. And, as MacDonald puts it: “this is a very promising start.”

A pre-print version of the study can be viewed on arXiv.