Sports

Jimbo Fisher envisions coaching return, but timing and situation are key in current college football climate

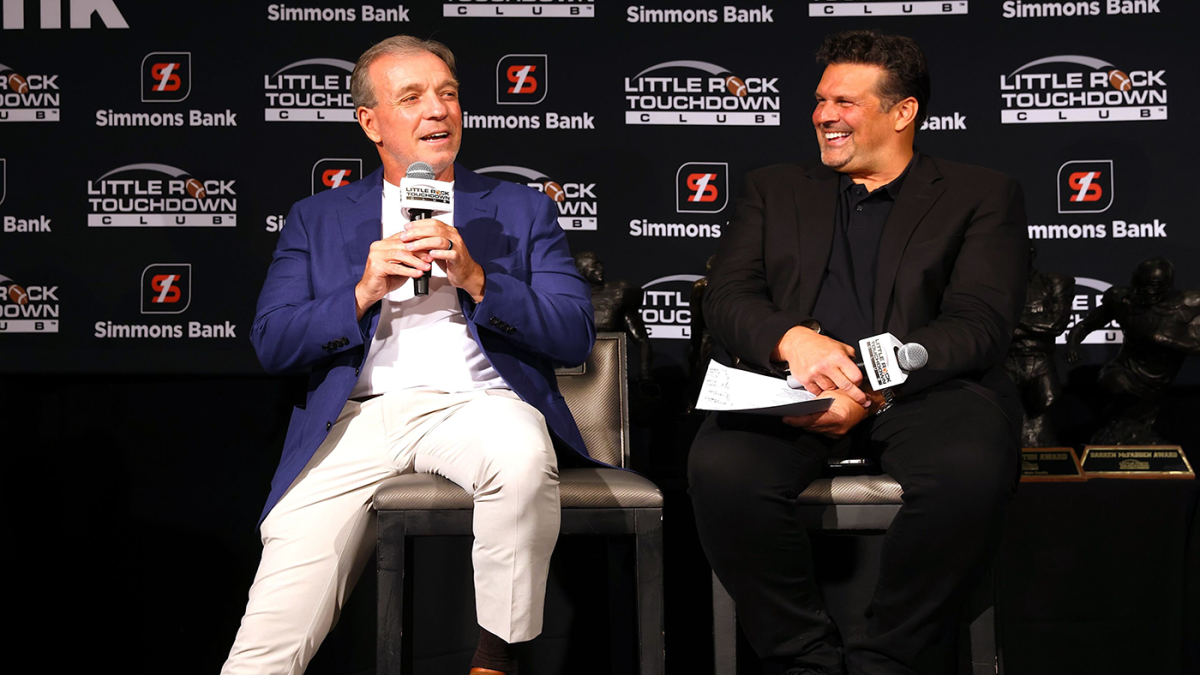

LITTLE ROCK, Ark. — Jimbo Fisher is practically glowing as he talks about a recent trip to southern Colorado, the beauty of the outdoors and how relaxing it was to lay in bed on a Monday night in the middle of the college football season.

The avid hunter shows a reporter a photo from his latest excursion and his latest kill: a giant elk he took down with three shots from a.300 Winchester Magnum rifle from a distance of 280 yards. “Never moved over 5 yards, then went down,” he says, scanning the iPhone screen with his eyes, reliving the moment tucked far away in the mountains and fields of the Colorado countryside.

“I didn’t care who got a first down, who was on the injury report,” Fisher said earlier during an appearance in front of several hundred football fans at the Little Rock Touchdown Club in Arkansas. “I was thinking I could be in practice right now. We would have just finished corrections from the week before, so I would have been mad. I would have been worrying who was working, who was doing what or I could be skinning this (elk). I like where I’m at. It wasn’t bad, at least for one fall anyway.”

Fisher is itching to get back into coaching, but he’s not pushing the issue right now as his first year outside of the sport since he was a player in 1988 inches toward October. “For one year I want to see my family, do nothing, hunt a little bit and take time,” Fisher told CBS Sports. “I’ll do some radio at home, and then decide what I want to do after that.”

Fisher was fired in November 2023, six seasons into his stay at Texas A&M, and is set for life with a $76 million buyout, the highest in the sport’s history. He underwhelmed fans and bosses at the school, where he was expected to deliver a national championship just as he did at Florida State in 2014. Instead, Fisher’s teams averaged nearly five losses outside of the pandemic-shortened 2020 year when the Aggies went 9-1 and finished No. 4 in the polls.

He’s watching games, keeping tabs on players across the sport and making notes for a weekly appearance on SiriusXM Radio, but he’s also preparing for the opportunity to lead another program. Friends deliver him game film, and he calls coaches across the country to bend their ears about X’s and O’s.

“To say (I’m) out is not true, you know what I’m saying?” Fisher said. “It’s gotta be the right situation, right time and a good thing. I never coached for money in the first place. I made money. I just happened to get tapped on the shoulder and got opportunities, but at the same time, there’s still a lot I think I can give the game and still coach.”

Fisher knows what many will think when he mentions money. “Well, you just got $70 million. Yeah, yeah, it’s easy for you to say.” Earlier in the day, he waxed poetic about his first decade in the sport as an assistant at Samford and Auburn, where he says he never made more than $57,000 annually on one-year contracts. At LSU under Nick Saban, he got his first big break, a two-year contract starting at $120,000.

“I would have still been coaching today. I never dreamed I’d be able to make that much money,” Fisher said. “From great advice from Bobby Bowden, I fell into that because I had success, and people tapped me on the shoulder and asked me for an opportunity. I would have never coached for money. I would have coached for the $30,000, $40,000, $50,000, $60,000 (that) high school coaches, junior high school coaches coach today. … Whatever level you coach at doesn’t make you a better coach because you’re getting paid more money. It’s the love of the game, and the interaction with the people and the kids and the families. I never dreamed I’d be able to make that. I’m a coal mining kid from West Virginia.”

Most of Fisher’s conversations with CBS Sports, and during his appearance at the Little Rock Touchdown Club, dealt with the evolution of college athletics, mainly how money has introduced more inequity into football. He’s concerned that parity will soon be washed away as the blue bloods in the sport draw the best players to their campuses with their deep pockets tied to NIL collectives. And soon, the introduction of revenue-sharing in the sport as soon as the fall of 2025 when schools can disperse as much as $22 million to athletes across all sports will further alter the landscape.

“People don’t realize that Alabama, Georgia and all of them ain’t got that money,” Fisher told CBS Sports. “They’re not like Ohio State, Texas. There’s a difference within your own conference, in my opinion. Maybe you make it $16 (million) or $18 (million) so the other mid-level schools have a chance. I just hate taking the Big 12 out of this, the ACC. I mean, it’s crazy to me. You think of the national championship between Miami, FSU, Clemson … it’s still a shame to me.”

Again, Fisher knows what you’re thinking. Isn’t this the same guy who signed the best recruiting class ever in the history of 247Sports with oil money fueling Texas A&M? He’s still fuming nearly three years after a message board poster alleged Texas A&M had a $30 million NIL fund. The rumor went viral through the traditional media, leading to a narrative that carried over into coaching circles — and even prompted a verbal spat between Nick Saban and Fisher after the Alabama coach told Tide supporters in May 2022 that the Aggies “bought every player” to secure the No. 1 recruiting class.

“The BroBible story that we spent $35 million on a recruiting class, my God, I wish I had $35 million,” Fisher said at the Little Rock Touchdown Club. “Not true.”

Fisher later told CBS Sports the overall NIL budget for A&M’s 20 athletics teams in 2021-22 was under $1 million. When stories of multi-million dollar NIL deals spread like wildfire online, Fisher said his phone lit up with calls from players and families.

“‘Where’s my money?'” was the general question, he said. “Why I came out and went against it as much as anything was because families were calling and saying, ‘Coach, I wasn’t bought.’ It was the families of the kids they were talking about. You don’t think about that avenue of it because they kept getting questions, too. That’s why I made the statements I made.”

USATSI

Fisher worries that the next wave of NIL and revenue sharing will lead to further consolidation of power, both within the sport and within athletics departments. “What I fear is there’s only gonna be like three or four male sports and about five or six women’s sports, and that’s it.”

Meanwhile, he says, smaller schools — even those within the Big Ten and SEC — could become feeder systems for the blue bloods. Already, he believes, some players at Group of Five schools view games against big-time opponents as a tryout that results in a bigger payday and a new opportunity at a different school. “You become a glorified junior college,” he said. “That’s sad to say, but that’s the only way I can look at it.”

He wants to see a salary cap, much like the NFL, in college football, but the only way for that is to form a player’s union with antitrust exemptions from the government. He also sees a growing problem with game officials in college football, and how it seems officiating practices vary from conference to conference. He wants a centralized, national training facility for officials and a national organization that pays referees like a full-time job rather than a fun side gig on the weekends.

“Here’s what bothers me,” he said simply. “No one has stepped up and wants to do what’s right for college football. There needs to be a commissioner.”

Fisher’s beliefs are common among coaches, though few share their issues to the public out of fear of ridicule.

Doesn’t the unequal budgets for NIL at schools affect how Fisher will approach the job market should he return to coaching?

“Whether it’s one of those schools or the SEC, the Big 12, it doesn’t matter to me,” he told CBS Sports. “If we can have some relevance and have some kind of ability to match some of that stuff, then you go with it. You’ll figure it out as you go. But still, I just miss the game. You miss the relationships and practice and all that stuff.”

As for what he’s seen this season as an observer, Fisher has been impressed by Alabama, Georgia, Miami, Penn State, Ohio State and Tennessee. He’s especially fond of Tennessee quarterback Nico Iamaleava and Miami’s Cam Ward. No. 1 Georgia and No. 4 Alabama meet this week in Tuscaloosa with the Tide opening as home underdogs for the first time since 2007. “It’s gonna be a donnybrook,” Fisher said, adding that whichever team’s receivers step up will be the winner in a one-possession game.

Fisher is still deeply entrenched in the game. The question is whether he will be on a sideline next year.

“If it’s the right situation and the right thing, yeah, probably so to say it 100 percent. But I know myself, and I’m still young enough to feel good and in great shape,” he said. ” I also think sitting back a year, getting perspective on some things, catch your breath, it’s been good. Yeah, I probably do.”

For now, Fisher is doing just fine, splitting time at a ranch outside College Station, Texas, and at his home in Tallahassee, Florida. He’s traveling the countryside, hunting big game and watching his stepson play football on Friday nights.

As his mentor, Bobby Bowden, once told him: if he’s wanted, somebody will eventually tap him on the shoulder.