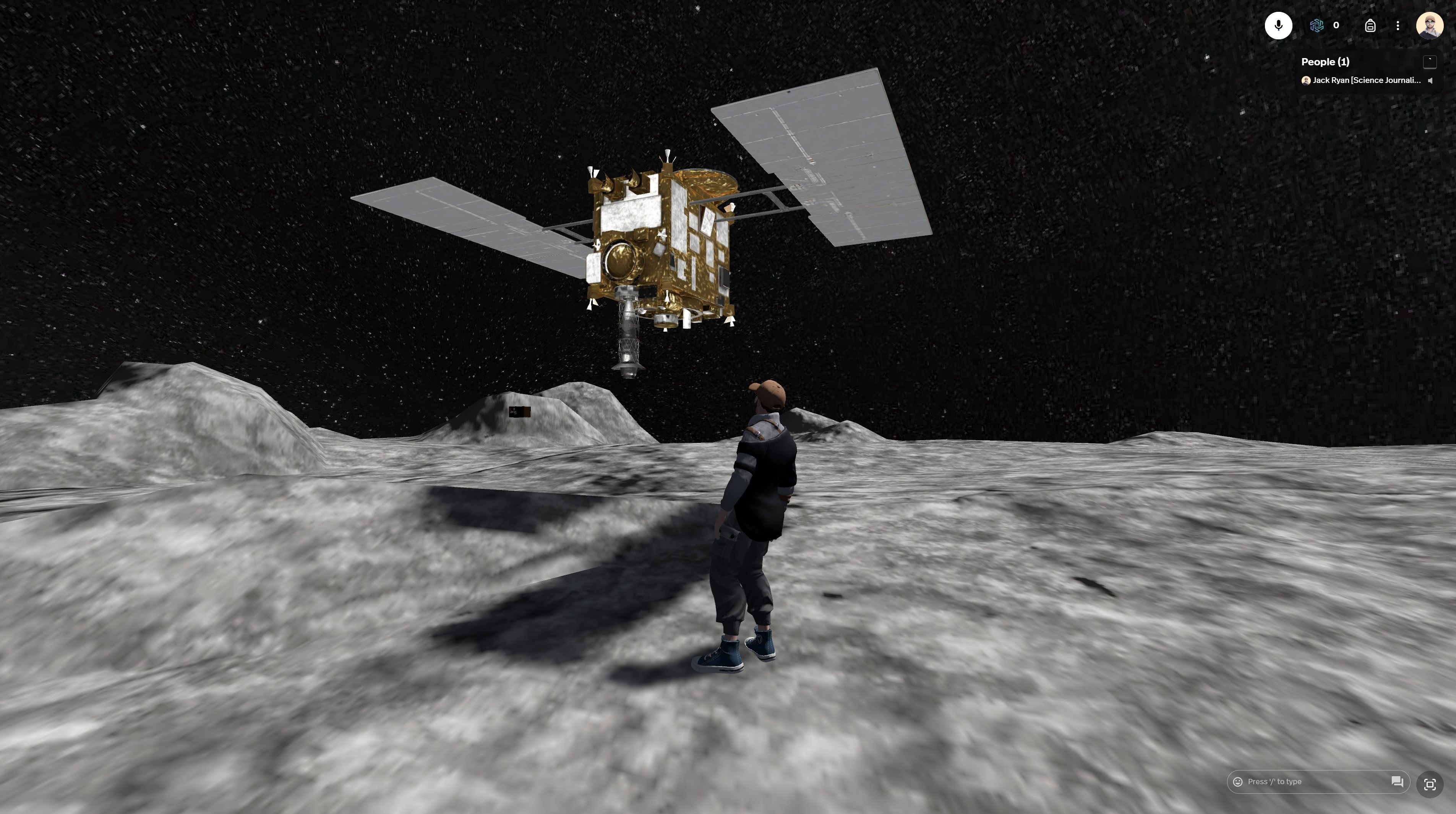

I’m standing so close to JAXA’s Hayabusa2 asteroid lander that I could reach out and touch it. Instead, I jump on top of it. Then I strike a pose. When I leap off, I float for a moment in the low gravity before touching down gently on the surface of Ryugu, a craggy, gray world devoid of life and color.

The “I” in this situation is my avatar, a digital approximation of myself that has a more consistent beard length and isn’t constantly rubbing sleep from its eyes. The Hayabusa2 spacecraft I stood on, and the asteroid beneath, are digital avatars too, recreated in virtual reality.

The VR experience I was in forms part of the 2024 Astronomical Society of Australia’s Annual Scientific Meeting, where the country’s astronomers come together to present new research, share results and mingle. This year’s meeting, in June, was almost entirely online, making use of the platform Spatial to provide attendees access to the conference in VR.

A digital venue, featuring poster halls, exhibition halls, meeting rooms and a lecture theater, was built by The Future of Meetings, an international collaboration working to make meetings more sustainable and accessible.

Related: Asteroid Ryugu holds secrets of our solar system’s past, present and future

I was initially a little trepidatious about attending the conference in VR. I’m a VR skeptic, having worked as a video games journalist and seen the up-and-down (mostly down) hype surrounding this technology. But as a space tragic and someone who stood on top of a dirt hill in Coober Pedy, Australia as samples from Ryugu came hurtling back to Earth in 2020, I would also describe myself as bloody excited to stand on an asteroid.

So, during the conference, I booted up Spatial, ran my avatar through the Exhibition Hall and plunged him through a portal to Ryugu and the spacecraft that visited it in 2018. It kind of felt like I was playing Super Mario 64 and had jumped through a portrait.

Immediately, I dropped onto the surface of the asteroid. The Ryugu model was created by OmniScope, a start-up founded by astronomer Sasha Kaurov to create virtual worlds for science outreach, using real imagery captured by Hayabusa2. It isn’t a perfect replica but it certainly recapitulates the area surrounding the spacecraft’s landing zone — the shadowy plain that provided JAXA with a spot to touchdown and grab material back in 2019.

Elizabeth Tasker, a professor at JAXA and part of the agency’s outreach team, noted that it’s hard to establish whether the topology of Ryugu is to scale. However, she said, the models of Hayabusa2, as well as its lander and rovers, are to scale.

There’s not a lot to do in Ryugu World except marvel at the space, but that’s kind of the point. This isn’t a video game. It’s a tool. Particularly in space and planetary science, the appeal is obvious: Using data and real-world observations, we can visit places we will never be able to reach physically.

Tasker conducted a tour of the exhibit in Spatial during the ASA meeting, and pointed out particular aspects of the Hayabusa2 spacecraft — features that wouldn’t be quite as simple when presented in a PowerPoint slide. The digital 3D model provides a way to get up-close with the spacecraft and examine finer details, such as where its target markers and small carry-on impactor were stored during operation.

The Ryugu surface is not a complete asteroid, though. You can’t walk from one side to the other.

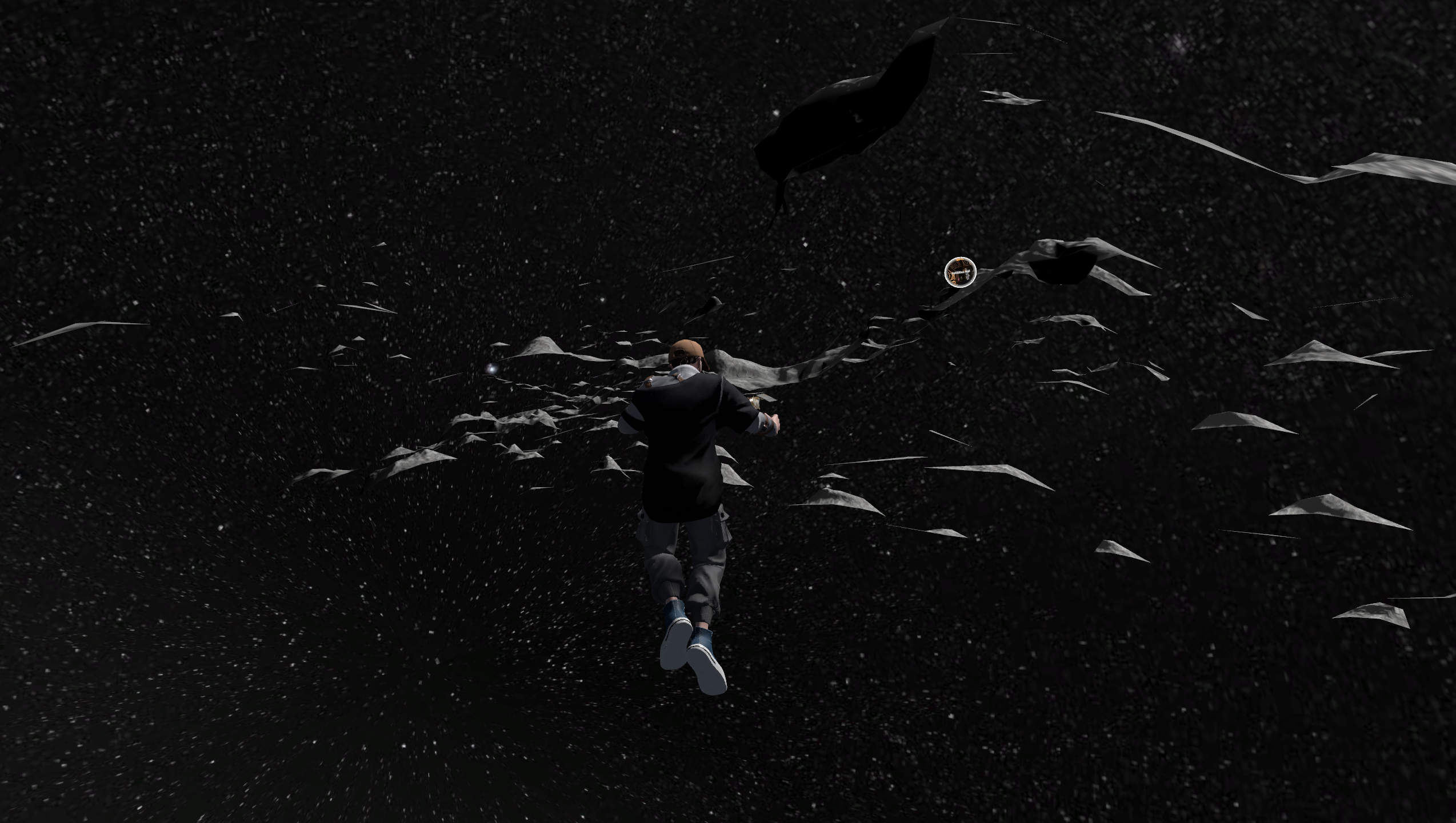

“I did mention at the end of the tour that it was possible (and quite easy in the low gravity environment) to run off the end of the asteroid scene and fall into space,” Tasker said. “This was supposed to be a warning, but promptly resulted in at least one person heading for their (virtual) demise! Fortunately, after falling for a short time, you are reborn back on the asteroid surface.”

Standing on the VR surface of an asteroid, something happens in your brain that makes the experience sticky. I’ve written more words about Ryugu’s surface, its chemistry and importance in planetary science than most, but being able to stand on it, even digitally, provided a real “oh, damn” moment — an appreciation of the difficulty in landing on a tiny rock, floating millions of miles from the Earth.

Of course, when I was finished, I jumped off the edge.