World

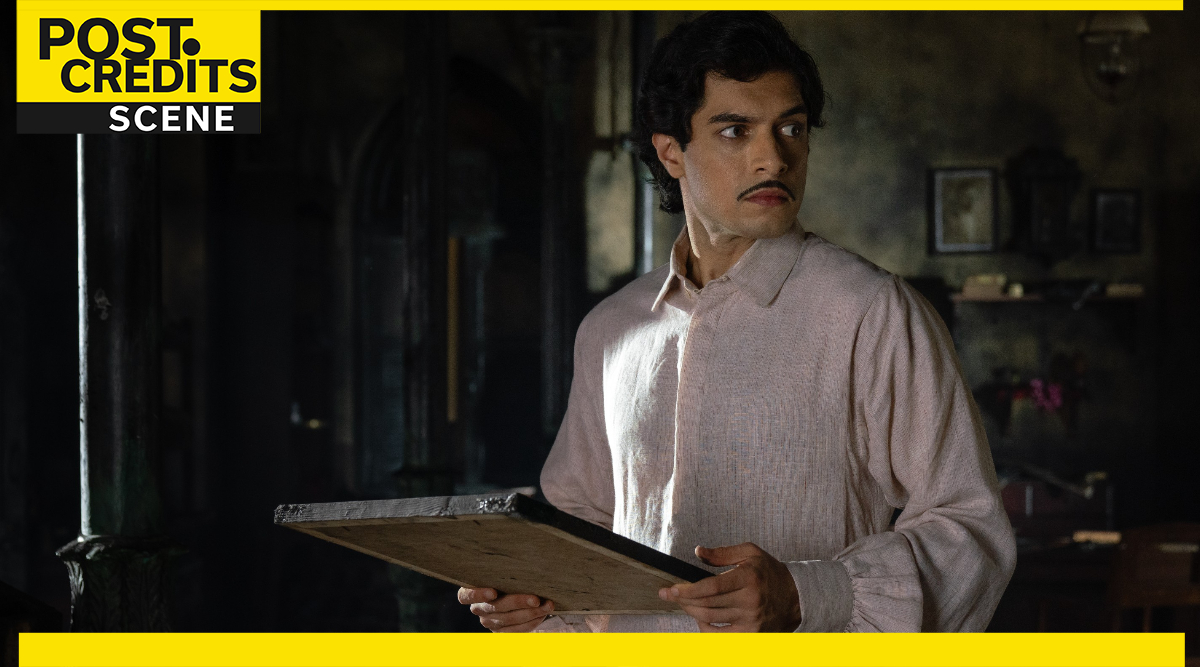

Maharaj: Junaid Khan plays the world’s biggest red flag in Netflix’s monumentally misguided period drama

Not five minutes have passed in the new Netflix film Maharaj and the young Karsandas Mulji has already announced to the world that he is a feminist. Walking home from the temple one day, the 10-year-old Karsan can’t help but ask his father why women are expected to cover their faces at all times. Later, he makes a bold speech calling for the normalisation of widow remarriage. Born in Gujarat — the film’s opening scene makes it seem like we’re witnessing the birth of Moses himself — Karsan grows up to become a journalist, operating out of ‘Bombay’ in the 1860s. His entire life, it seems, revolves around how he can make the world a better place for women. Somewhere out there, Babil Khan probably punched a hole in the wall, wondering why he wasn’t cast in this role.

But another nepo-baby beat him to it. Maharaj marks the acting debut of Junaid Khan, son of Aamir Khan. And while there would have been plenty of reasons for him to get excited about this project — it’s based on a landmark court case; it’s also technically a biopic, and its politics are seemingly above reproach — nothing about the finished film suggests that it has a single progressive bone in its body. In fact, Karsan is the biggest red flag protagonist that Hindi movies have produced since Ranbir Kapoor’s Vijay in Animal.

Shalini Pandey as Kishori in Maharaj. (Photo: Netflix)

Shalini Pandey as Kishori in Maharaj. (Photo: Netflix)

While virtue signalling is always a little suspicious — this is practically all that Karsan does — it isn’t a crime. But there’s a noticeable dissonance in what he says and what he does. He’s engaged to Kishori, a young woman played by Shalini Pandey, who is introduced with — of all things — a song and dance number. This isn’t exactly like the ‘item number’ with which Kriti Sanon’s character was introduced in another faux feminist movie, Mimi, but that doesn’t mean she isn’t leered at by at least one man. He’s the titular Maharaj, a local priest played by Jaideep Ahlawat. Claiming to have been impressed by her dance performance, the Maharaj invites Kishori to his chambers for some sort of initiation ritual. She agrees, having been brainwashed by her community into thinking that it is some kind of holy rite of passage. But the Maharaj rapes her, and that too in front of viewing public.

Karsan stumbles onto the scene — remember, the movie has already established that he’s progressive to the point of being annoying — and proceeds to shame not the Maharaja, but Kishori. It’s a shocking moment, but you wait patiently, assuming that the movie is setting up some sort of redemption arc, or, at the very least, a third-act transformation. But for redemption to be possible, there must first be an acknowledgement of a moral misstep. The problem with Maharaj — naming it after the villain should have been a tell-tale sign, by the way — is that it doesn’t seem to realise that Karsan is a terrible person at all.

“Tumse yeh ummeed nahi thi,” he tells Kishori, immediately severing all ties with her. This is his first instinct after watching her be assaulted. Karsan is apparently also the only person in the entire city who doesn’t know about the Maharaj’s misdeeds. After basically comparing her to leftover food — this is true — he begins to shame her in public. Things become so heated between them that Karsan even raises his hand to smack her on the face, stopping himself at the last moment. He’d get away with it in a court of law, but we all know that a man who contemplates hitting a woman is no different from a man who actually does. And a movie that claims to be progressive rarely ever is.

Sharvari Wagh as Viraj in Maharaj. (Photo: Netflix)

Sharvari Wagh as Viraj in Maharaj. (Photo: Netflix)

Maharaj’s muddled morality becomes obvious when a random man tells Karsan that Kishori must be given “sudharne ka mauka” now that she recognises her “galti.” The only thing that this does is to reinforce the false notion that Kishori is somehow to blame for what has happened to her. We never get a scene in which Karsan admits that he was wrong to accuse her of betraying him. And meanwhile, we’re meant to believe that his advocacy for “stree shikshan,” “ghunghat par rok,” and “vidva punarvivaah” has annoyed his conservative family to the point that they’re willing to disown him. They call it “ghatiya vichaar.”

But just when you think that Maharaj can’t get more outrageous, it falls back on the most problematic trope out there. Ashamed of the trouble that she has caused and after being disrespected in broad daylight by the man she loves, Kishori kills herself by jumping into a well. This is called ‘fridging’ — a sexist pop-culture cliché where female characters are maimed or murdered purely to serve as motivation for the male characters to evolve. Maharaj follows this trope to the tee, and Kishori effectively dies in disrepute.

After her death, Karsan resolves to write articles about the Maharaj and expose him for the creep that he is. The court case that we were promised in the opening moments of the movie is pushed to the final 20 minutes. Before that, however, he begins a new romance with Viraj, played by Sharvari Wagh. It’s like the movie itself is disrespecting Kishori’s memory; within 15 minutes of her death, it has already found a replacement. And it’s not like he ever grieved her loss in the first place.

Read more – Ae Watan Mere Watan: Heartbreaking, the worst film you’ve seen just made some strong political points

Jaideep Ahlawat as Maharaj in Maharaj. (Photo: Netflix)

Jaideep Ahlawat as Maharaj in Maharaj. (Photo: Netflix)

Sounding an awful lot like Hansa from Khichdi, Viraj barges into Karsan’s office one day looking for work. But for all his claims about wanting to empower women, when an opportunity to do so literally walks into his life, Karsan does what only a red flag would. He agrees to hire Viraj, but on the condition that she works for free. If this isn’t exploitation, what is? To make matters worse, the movie doesn’t appear to realise that this tiny detail pushes its protagonist further into irredeemable territory (as if abetting suicide wasn’t enough). True to form, Maharaj neglects to spotlight the numerous women who’ve been abused by the priest. In addition to being named after the villain, the movie chooses to present their story from a guy’s point-of-view instead. Even the climactic courtroom sequence is centred on Karsan, whom you could be fooled into thinking has secretly passed the bar exam and become a barrister, going by his pick-me attitude.

This is a particularly damaging perspective issue that Hindi movies succumb to with disappointing regularity. In fact, Shalini Pandey herself was ignored in Jayeshbhai Jordaar, another YRF movie that she should ostensibly have been the star of. But Maharaj is more like a second cousin to the Manoj Bajpayee-starrer Sirf Ek Banda Kaafi Hai — a similarly themed courtroom drama whose title alone should indicate how oblivious it was about its sexism. Let it be known that “sirf ek banda” is never enough. Bollywood must understand that the first step in empowering female characters is to stop ignoring them in their own stories.

Post Credits Scene is a column in which we dissect new releases every week, with particular focus on context, craft, and characters. Because there’s always something to fixate about once the dust has settled.