Bussiness

Monitoring Minneapolis Police: The business behind overseeing court-ordered reforms

Monitoring Minneapolis Police: The business behind overseeing court-ordered reforms

The Minneapolis Police Department (MPD) is facing an unprecedented challenge: two sets of court-ordered reforms.

Last year, the city entered into a settlement agreement with the Minnesota Department of Human Rights after an investigation found MPD engaged in a pattern or practice of race discrimination.

A similar, federal investigation is expected to result in a separate consent decree, overseen by the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ).

The critical piece of both agreements is the independent monitor, a position that holds tremendous power and influence. The monitor, typically a group of individuals, will track MPD’s progress on the reforms and will ultimately recommend to the court when the oversight should be lifted.

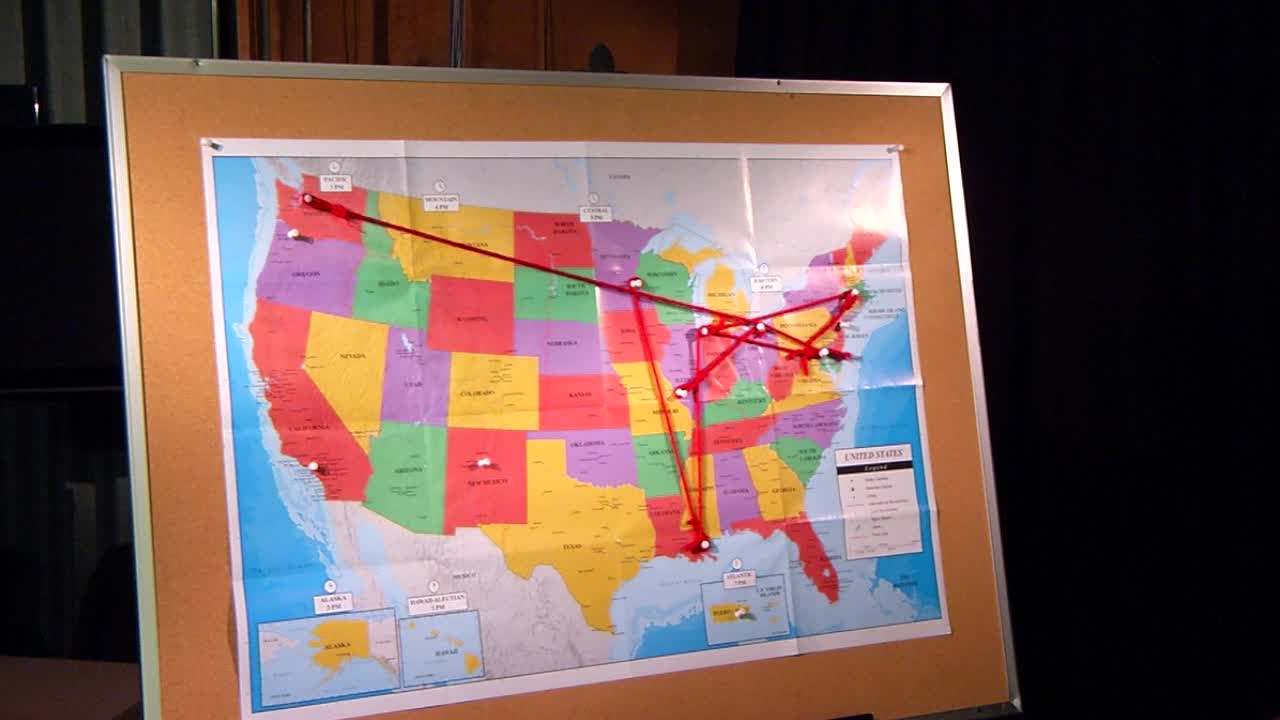

Despite a growing need for monitors, a review of federal consent decrees across the country by 5 INVESTIGATES shows a small number of people doing this work in multiple cities.

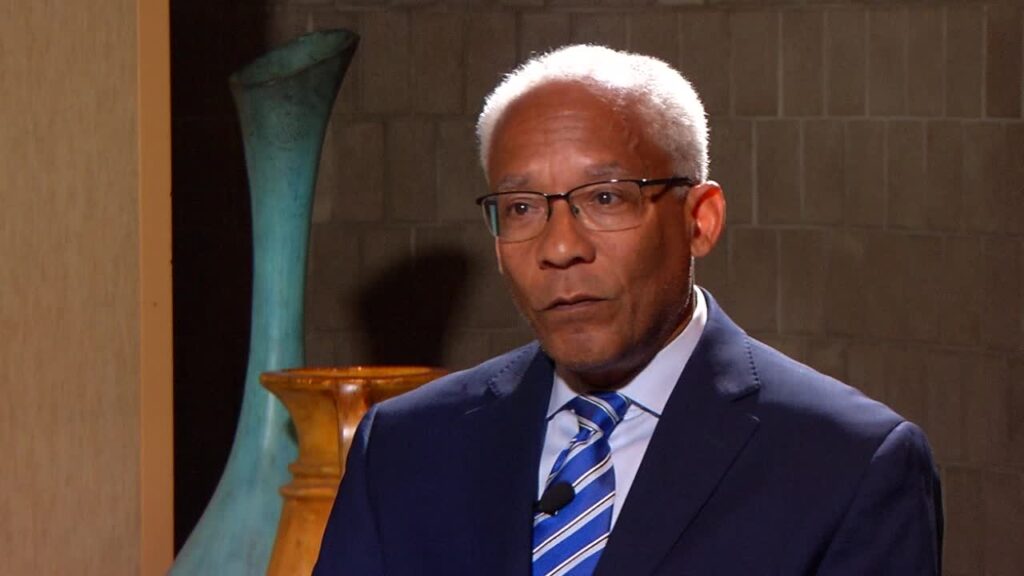

Among them – David Douglass, the man chosen to lead the oversight of Minneapolis Police.

In March, the city signed a contract with Douglass’ nonprofit, Effective Law Enforcement For All, to serve as the independent evaluator overseeing the settlement agreement with the state.

Douglass is also the deputy monitor currently overseeing the federal consent decree between the U.S. Department of Justice and the New Orleans Police Department.

In an interview with 5 INVESTIGATES, Douglass said his work in New Orleans is winding down.

“We are all here and committed to devoting as much time as it’s necessary to get this work done,” he said.

However, the specialized nature of monitoring police departments under consent decrees, paired with the small pool of candidates, has prompted criticism that the niche business is a “cottage industry.”

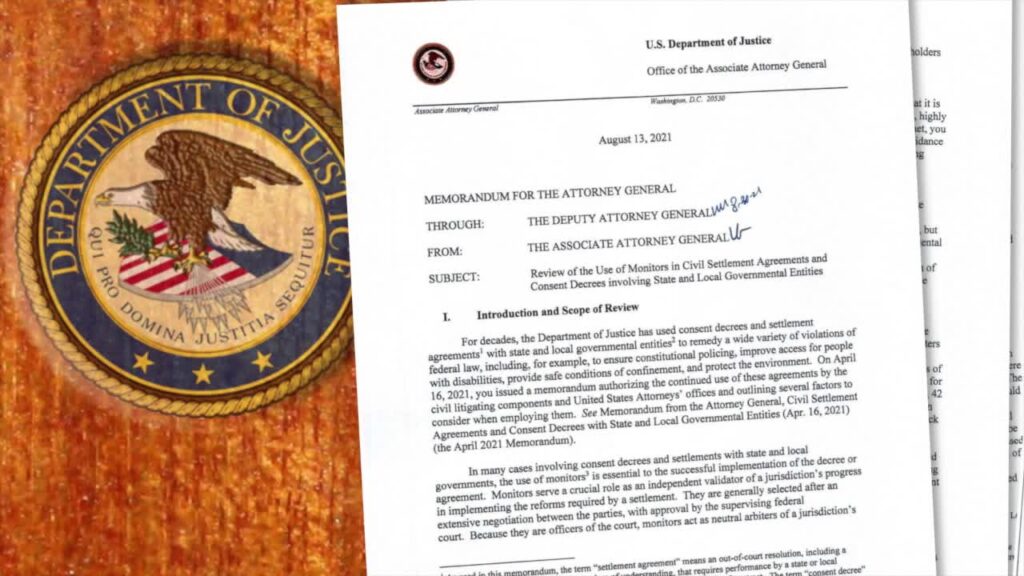

In 2021, U.S. Attorney General Merrick Garland ordered a review of the use of monitors in consent decrees and other settlement agreements.

During the review, stakeholders urged the department “to do more to dispel the perception that monitoring is becoming a cottage industry, closed to outside voices,” according to a memo published months later.

Douglass said he doesn’t believe monitoring is a cottage industry.

“There is a monitor because the Department of Justice has identified a need,” he said during the interview. “To the extent that there is a need, then the need should be addressed. And I don’t know that I’m particularly troubled if there is an industry designed to eliminate decades – and in some sense, in some instances – centuries of policing that hasn’t been safe and effective for large segments of the community.”

DOJ recommendations

The DOJ memo laid out recommendations for using monitors in future consent decrees, including restricting the lead monitors’ participation in multiple consent decrees.

“Jurisdictions should not be deprived of subject matter experts whose unique knowledge makes them an asset to multiple monitorships,” the memo reads. “But the person serving as the lead monitor should be solely committed to the jurisdiction they are serving.”

When asked if anyone from the City of Minneapolis or state Department of Human Rights raised concerns about his continued involvement in New Orleans, Douglass said it was discussed, but that he wouldn’t characterize it as a concern or issue.

He said cities benefit from the experience monitors bring from other consent decrees and pushed back on the justice department’s recommendation.

“I don’t think there should be arbitrary rules about it,” he said. “I think each monitor should be judged on their track record.”

Christy Lopez agrees.

Lopez worked for two decades in the Civil Rights Division of the U.S. Department of Justice. She led multiple high-profile investigations of police departments, including in Ferguson, Missouri, after the death of Michael Brown.

“When people identify a monitor or monitoring team that they have confidence in, city leaders, DOJ, they want to go back to that same person or that same team,” she said.

But Lopez said consent decrees are expensive for cities, and the concern that a monitor may prolong their work to make more money is justified.

“I have seen a couple of monitors take that approach, and I try to call them out when I can,” she said.

Time is money

Last year, 5 INVESTIGATES analyzed consent decrees in a dozen other cities and found those mandates last an average of nine and a half years before the oversight is lifted.

Contract and invoice data show those cities have spent anywhere from $9 to $12 million on monitoring fees.

In its contract with ELEFA, the City of Minneapolis capped the budget at $1.5 million per year.

Douglass said the best way a city can reduce cost is for a city to work quickly to implement the reforms and sustain that work.

“We’re very committed to achieving change as quickly as we can, but it’s more important that we do it in the right way so that’s lasting,” he said. “If the city does its part, I think it can be out in four or five years.”