Fashion

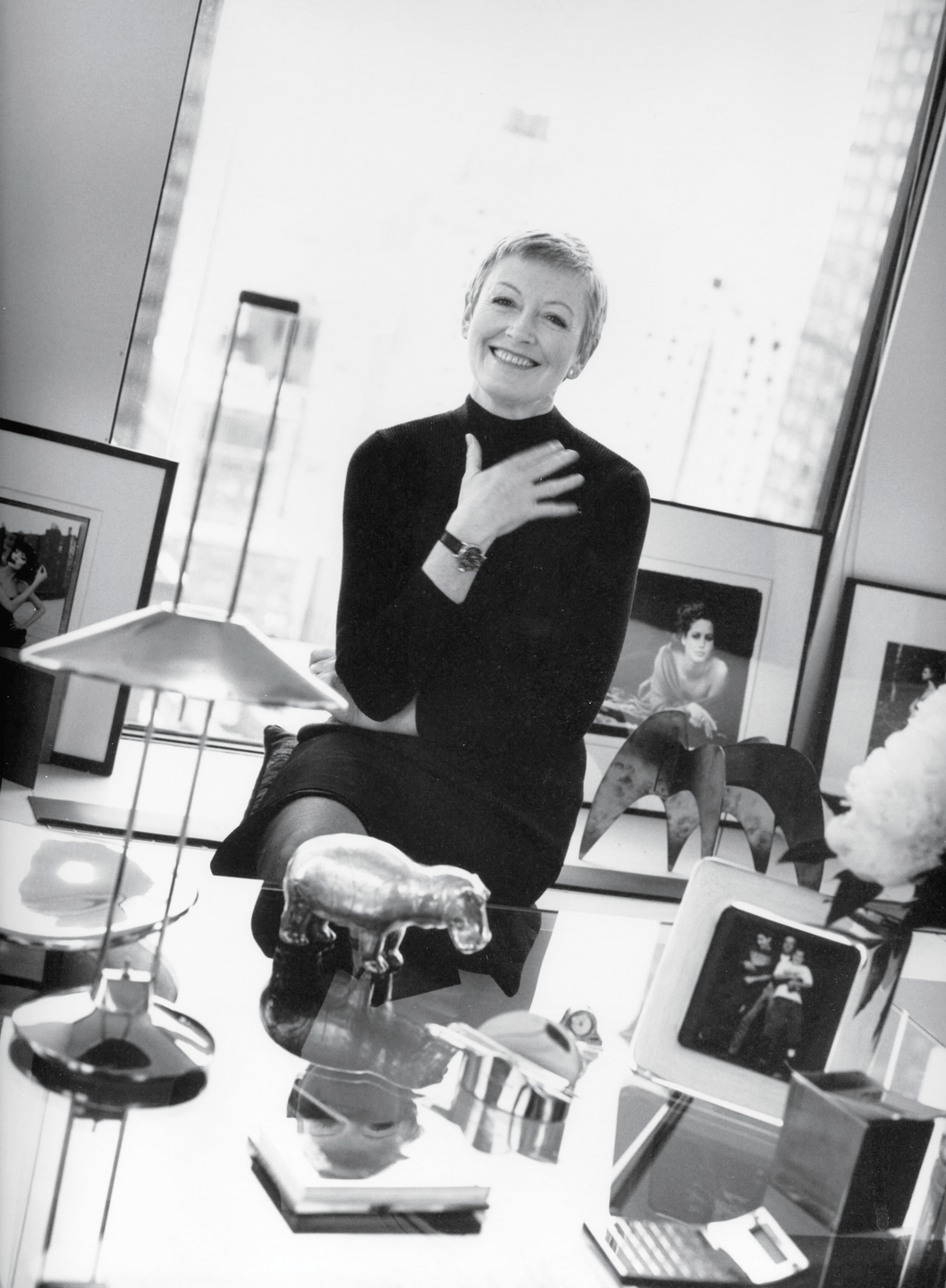

My Mother’s Work at Harper’s Bazaar Was About Much More Than Fashion

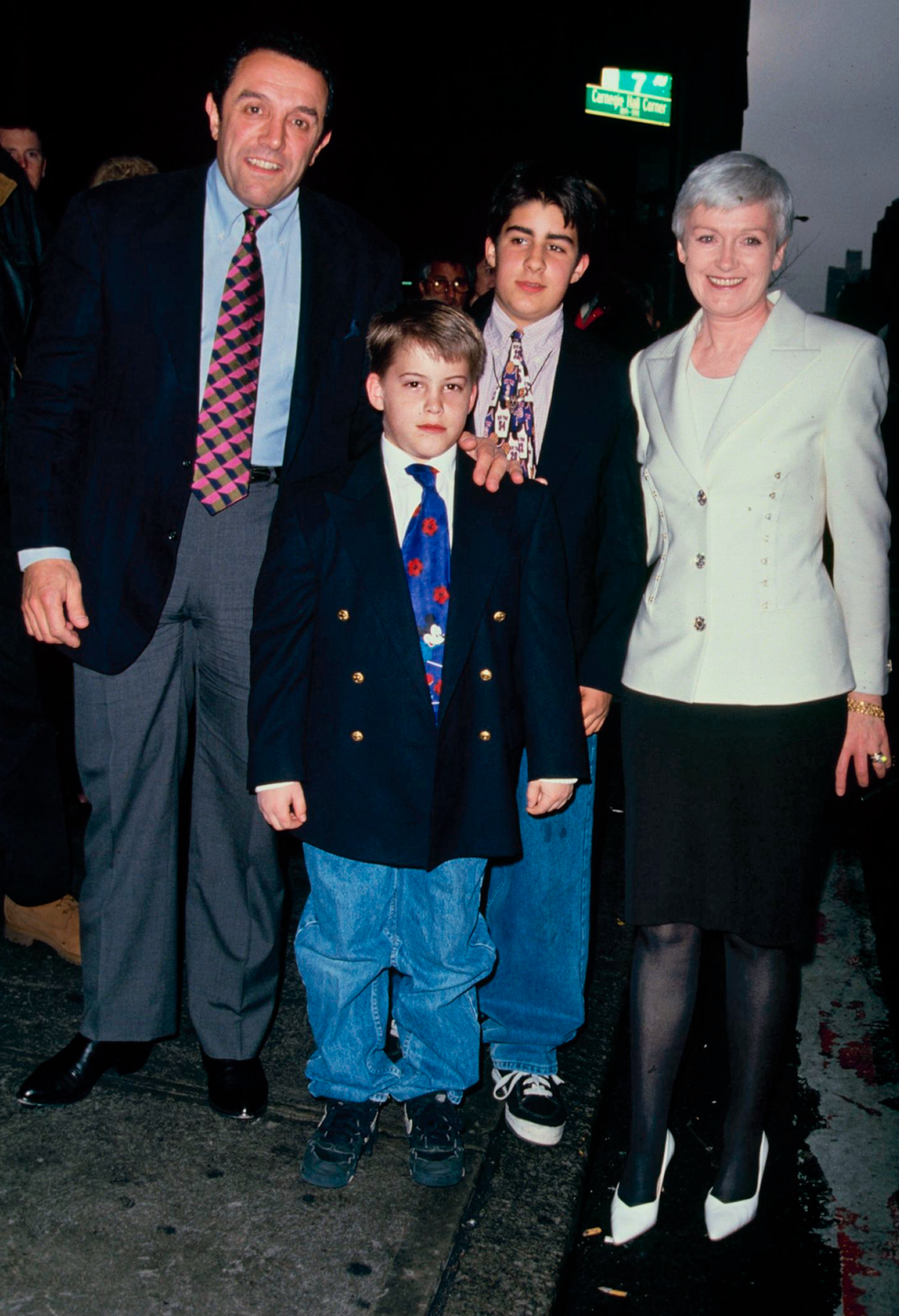

I was seven years old when my family moved to New York from London. It was January of 1992, and my mother had just been named editor in chief of Harper’s Bazaar. She’d been the editor of Vogue in the U.K., where both my parents were from. She loved that job, having started out at the magazine two decades earlier as an assistant. We had family and friends in London. One of my earliest memories involved presenting flowers to Princess Diana. She and our mom had gotten to know each other during her time at Vogue. Looking back now, it all seems a bit surreal. But even as a kid, I had this strong sense that it must have taken a pretty special opportunity for her and our dad to leave all that behind and move with me and my older brother, Rob, who was 11 at the time, across an ocean and around the world. The opportunity to come to the U.S. and reimagine a magazine like Bazaar was one she couldn’t pass up.

It was a big transition for all of us. I remember our first two or three months in New York, we lived in a hotel. The food was different. So was the weather. My brother and I had to learn about new sports, like baseball and basketball, and make new friends.

Our mom wanted to make sure that we stayed connected to our family in England, but at the same time she also wanted us to become fully engaged with the new one we found forming around us in New York. The fashion world is small, so we were very lucky to have people around us like our mom’s friend Grace Coddington, whom she’d worked with at British Vogue. Grace herself had relocated to the States after becoming creative director of the American edition. Our mom also knew Patrick Demarchelier, who was one of the first photographers to sign on with her to shoot for Bazaar. He, his wife, Mia, and their sons, Gustaf, Arthur, and Victor, were incredibly welcoming to us all—as were the editor in chief of Esquire at the time, Terry McDonell, and his family.

Our parents were always very open and honest with us about everything. My brother and I were both adopted, which is something we’ve known our whole lives. Before our family made the move to New York, they discussed the idea with us: why they wanted to do it, how we felt about it, what excited us or made us feel uneasy about it. Even though we were young, they were always very up-front with us about things that might affect us, and I always felt like they made a real effort to involve us in the decisions they were making for us and for our family.

That openness and honesty proved especially important when they told us that our mom had been diagnosed with ovarian cancer. It was December 1993, or just under two years after we’d moved. It also came during what should have been a celebratory time for our mom. The response to her reinvention of Bazaar had been overwhelmingly positive, and she’d more than settled into life in the U.S. She had even struck up a friendship with the nation’s new first lady, Hillary Clinton, who’d moved into the White House just months after our mom debuted her first issue.

Back then, there wasn’t really much of an internet to speak of—and very little information about ovarian cancer in general. The existing research really couldn’t explain what caused it or who was most at risk, though my mom suspected that fertility treatments she’d received in England in the ’70s—which were ultimately unsuccessful—may have played a role in the development of her disease. Our parents told us that her cancer was Stage III, that she was going to begin receiving treatment, and that there would be challenges ahead.

Most of our understanding of what ovarian cancer was, though, came from what we saw with our own eyes. Over the next five and a half years, we witnessed all the ebbs and flows in our mom’s battle with the disease. But through it all, our parents never tried to hide from us how she was feeling. Whenever she was in the hospital, we would visit her every day.

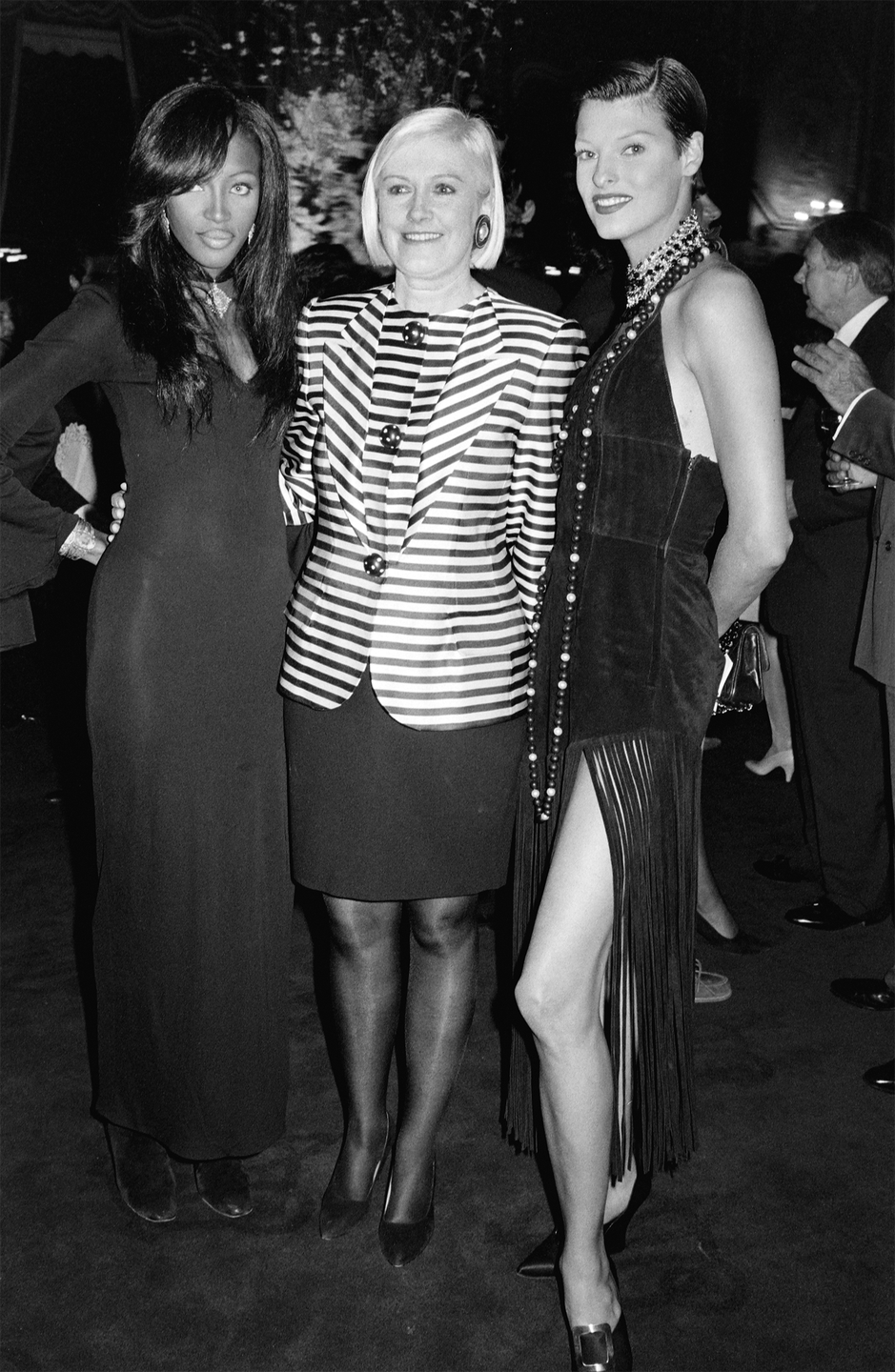

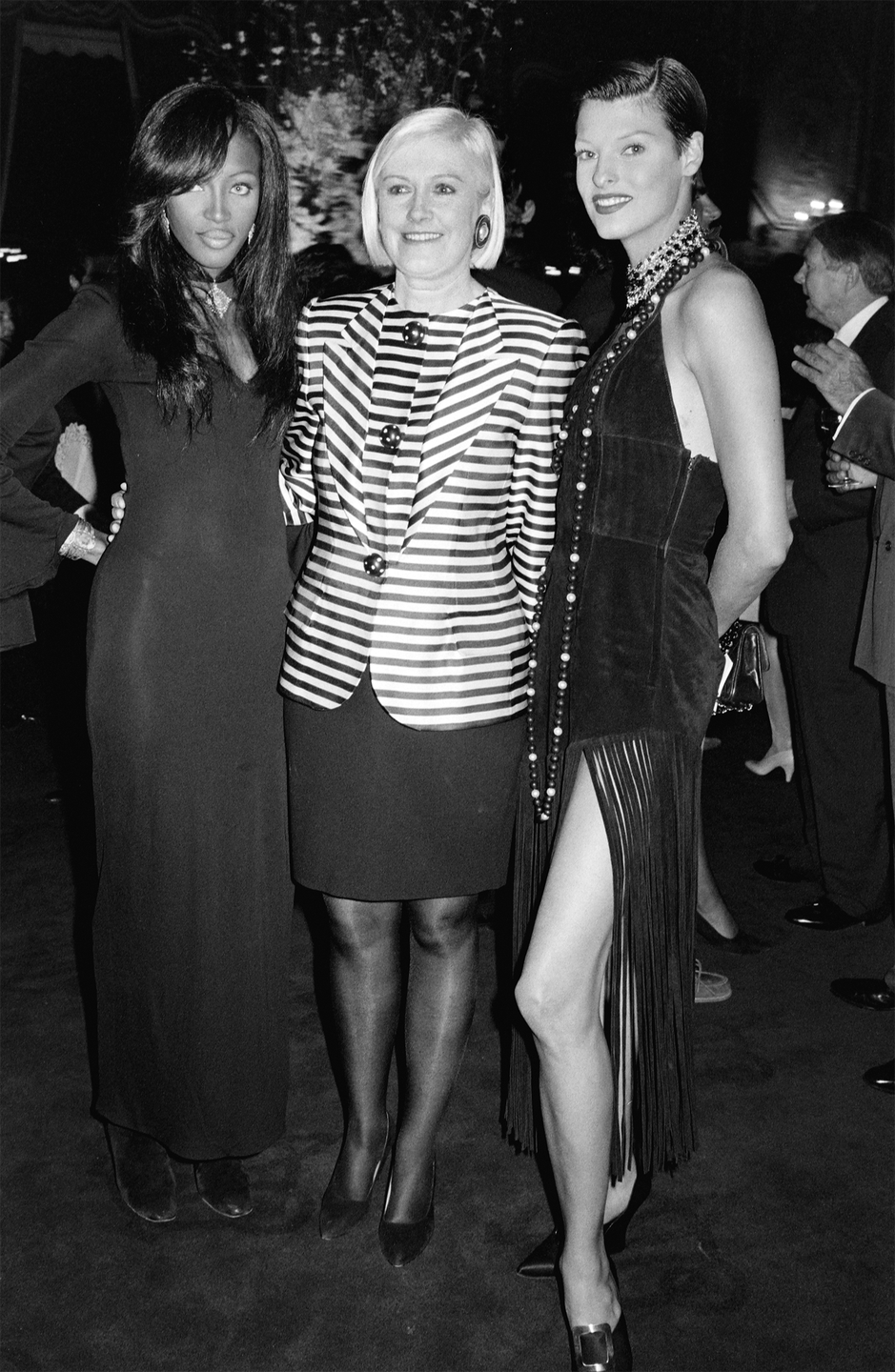

Our mom also refused to let her illness define her or stop her from doing things that were important to her. Even when she was in the hospital, she would hold meetings with the Bazaar team, going over fashion boards and making decisions. Working with people who inspired her—with people she trusted—was one of the things that she loved. In some ways, I think it actually kept her going. She was fighting for us as a family and trying to be there for us, but having that job meant so much to her. Not many people get to do something they love, and watching the way she seemed to understand and appreciate that has always stayed with me.

She was also very conscious of her time with us. We always had family dinners on Sunday, which is a very European thing, and she never let her job or her illness interfere with being a parent. She loved doing things like going on family vacations and hosting cocktail parties. Obviously, there were limitations because of her health, but I can’t remember ever hearing her say, “I can’t do that today.” She would find a way or find the energy to be a part of things—to be there as a leader, as a mother, and for the people in her life.

Our mom realized that as the editor of Bazaar, she had the ability to make a difference in other people’s lives. Not long after she started treatment, she began sharing what she was going through in real time with the magazine’s audience in her editor’s letters and a series of features on the latest science around ovarian cancer. Bazaar also became a place where she was open and honest—about what she was experiencing, the questions she had, the answers she sought, the uncertainty she faced. I can’t speak for my mom, but I think she felt that talking about things—even very difficult things, like an illness—helped give other people the space to talk about them. It was also a way of letting those people know that whatever they were going through, they weren’t going through it alone.

In many ways, that impulse is what led our mom to join the Ovarian Cancer Research Fund—now known as the Ovarian Cancer Research Alliance, or OCRA. She’d learned about the organization from her oncologist, Peter Dottino. Back then, OCRF was for the most part focused on funding medical research into ovarian cancer. But my mom, who became president of OCRF in 1997, saw an even bigger opportunity to increase awareness around the disease and help patients like her and families like us, who were living with it.

Raising money to find new treatments—and a cure—for ovarian cancer remains OCRA’s core mission. But today the organization functions on multiple fronts, supporting and advocating on behalf of patients and caregivers and focusing on improving outcomes as well as prevention.

September is Ovarian Cancer Awareness Month. While our understanding of ovarian cancer has advanced in the three decades since our mom was diagnosed, there is still no cure or reliable way to screen for it. It has often progressed significantly before any symptoms are even present. That’s why early detection is crucial. Genetic testing is now more widely available, and OCRA encourages anyone who has a first-degree relative, like a parent or sibling, who has been diagnosed with any form of cancer to be tested. (More information about OCRA’s work, as well as recommendations and resources, can be found at ocrahope.org.)

It’s been 25 years now since our mom passed away, in April 1999. It’s still always so nice to hear from people whose lives were touched by her or her work, as both an editor and an advocate. I know that her determination to talk about her own experience, inform people about the disease, and raise money for research—and her passion for trying to help others—had a profound impact. But I think it all comes down to who she was as a person—and that openness and honesty. That, for me, was what was at the heart of everything she did.

You Might Also Like