Fashion

Natavan Aliyeva: Bold heritage meets sustainable fashion in Baku

To understand what makes Natavan Aliyeva the hottest designer in Baku right now, you first need to forget everything you think you know about Baku. Forget Hamida Omarova, Muslim Magomayev or Rustam Ibrahimbekov; forget black leather jackets, trench coats, eight-sided flat caps and summer slippers. Forget Richard Sorge in Sabunchu and Tahir Salahov in the Black City.

The Baku of Aliyeva, the designer of NATAVAN, is not that Baku. Instead, it is the Baku you might recognize if you were gripped by the latest series of gritty Azerbaijani crime thriller “Scorpion Season.” It is the city we glimpse through the eyes of experienced detectives, a city of teahouses and fast cars, a city where glamour means everything and Botox rules, a city where every street corner hums with a different language, not a melodious Vagif Mustafazadeh soundtrack.

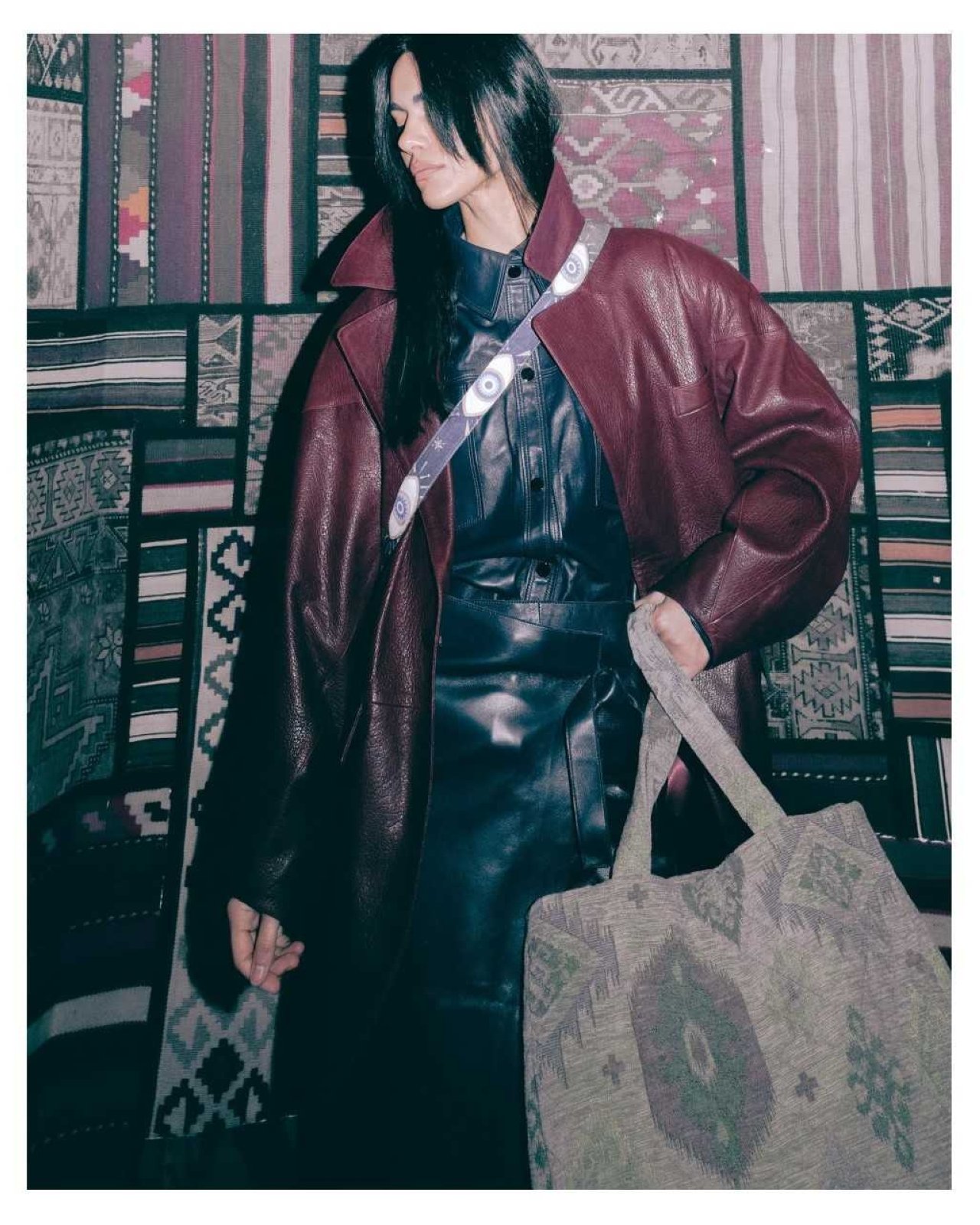

A few days ago, Aliyeva showed her new collection on a makeshift catwalk marked out on Baku’s cobbled streets, models walking between stalls loaded with floral ornaments, piles of Azerbaijani rugs inside the Inner City walls. As a venue, it was about as far from the tropes of fashion week – glitzy hotels, luxuriously neutral all-white pavilions – as it is possible to get. The models wore kelaghayis and bandanas, slogan T-shirts and knitted cardigans.

“I don’t think elegance is relevant at the moment,” says Aliyeva, cheerfully. It is the week after the show and she is holed up in her cozy Baku studio, trying to fend off a heat wave in the brief lull before buildup for her next show. “NATAVAN is about the street and on the street, I don’t think elegance is what people are aiming for. So, opt for stylish, yet comfortable clothing that allows for movement.” At this show, which Aliyeva styled personally, the models were dressed early and spent time chatting before the event began. As a result, the clothes looked slightly lived in.

“We do things differently here. If we look at history, corsets promoted superficial indulgence in fashion as well as the obvious health risks, including damaged and rearranged internal organs, and compromised fertility. As a result, when we put on clothing, we must pay attention to its components since it often enters our body, which can impact our overall health.”

The articulate tastemaker doesn’t fit the mold of the flamboyant fashion designer. She’s dressed down, wearing one of her signature blazers. Natavan Aliyeva’s meteoric rise as a fashion designer can be credited to her interpretation of her Azerbaijani heritage through design.

“You can never go wrong with a kelaghayi,” says Aliyeva. “These fine silk headcovers have been produced in Azerbaijan for generations. It provided warmth during cold weather and shielded the wearer from the heat in hot weather.” This rationale – and the rhythms of following nature in her early developmental years – is what Aliyeva credits her appreciation of the earth and its resources to: “Azerbaijani national dress is closely connected to nature. From the design to the color scheme, there is a fundamental element of nature portrayed. It’s iconic, timeless, and it still inspires fashion designers even today.”

Aliyeva was born in 1983 in Baku. The stern Soviet aesthetic of her childhood was obliterated in 1989, with the fall of the Iron Curtain: unexpectedly, there was rock music, “Terminator 2,” Vogue magazine, a mix of contrasting visuals. “My Russian mother played a big role in my life,” Aliyeva says. “She loved everything about Azerbaijani culture: Carpets, local cuisine and traditions. As I have got older, I have recognized the importance of our culture as a source of pride and identity.”

“Taking risks is something I became accustomed to as a child and it’s embedded in the DNA of my brand,” she says. “In the fashion world, you need to take risks to survive.” NATAVAN has shown womenswear during haute couture week, adapting and evolving as the designer sees fit. Early on, buyers from Toronto who visited the designer’s showroom in the Inner City inquired about the brand’s minimum order. They were informed that there was no minimum order, only a maximum one. The brand’s strategy was to create buzz by ensuring that demand would exceed supply. The tactic raised eyebrows across Baku, but it proved successful.

Right now, Aliyeva has an obsession with sustainable fashion. “Just take a look at what’s happening all around us,” she says. “The impact of fast fashion on our planet is enormous. We are moving towards individualism so sustainable fashion that can make a real difference is key in any consumer’s journey.” The latest show also addressed in trademark blunt fashion the issue of Aliyeva’s creative debt to the legacy of her mentor Vyacheslav Zaitsev, known as the “Soviet Christian Dior” by the Western media. “He played a decisive role in my career. During my exam, he complimented me for the use of national motifs in fashion design,” she says.

In step with the zeitgeist, Aliyeva is as keen on technology as she is on authenticity. Digital accessories are being trialed on the computer screen, with a view to installing a part of her showroom that is purely digital. I ask her how she thinks this new technology will change fashion and she laughs. “We can’t escape technology and our dependence on it. We often say that a mobile phone is like an extension of our limb. But I think pretty much everything is going to change.”