Microsoft

Here at Ars, we’ve been around long enough to chronicle every single time that Microsoft has tried to get Windows running on Arm-based processors, instead of the Intel and AMD-made x86 chips that have been synonymous with Windows for more than three decades. The most significant attempts happened in 2012 with Windows RT, which looked like Windows 8 but couldn’t run any x86 Windows apps; and in 2017 when Windows 10 Arm PCs arrived with rudimentary x86 emulation.

The main PC company backing each of those Arm efforts was Microsoft itself, which launched the original Surface to showcase Windows RT and the first Surface Pro X during the Windows 10 era. Since then, Microsoft has periodically refreshed the Arm version of the Surface tablet while continuing to sell Intel versions. A couple of PC OEMs put out Windows RT tablets, and most of them took a stab at one or two Windows 10-into-11-era Arm PCs. But there was never a big unified push that made it clear that the entire consumer PC ecosystem had bought into Arm.

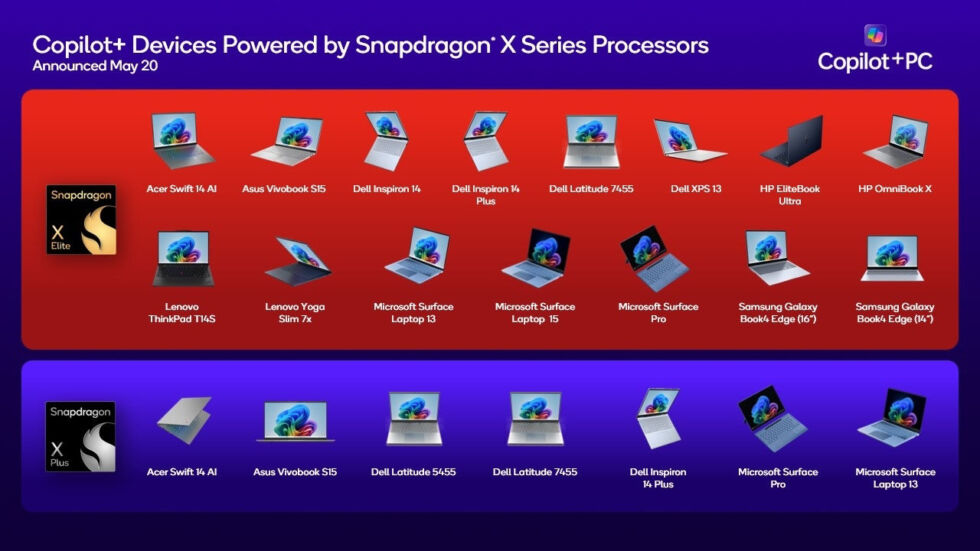

This week’s announcements felt different—yes, there was a new Surface Pro and Surface Laptop from Microsoft leading the charge (and the new Surface Pro is the first Surface Pro ever to ship Arm as the default option for most people). But the Surface launch was accompanied by a major wave of systems from essentially every major PC OEM, suggesting at least some level of elevated enthusiasm for the Snapdragon X series that didn’t exist for older Arm chips.

From Lenovo, you’ve got the Yoga Slim 7x and ThinkPad T14s Gen 6, variants of the company’s main consumer and business laptops. Dell is offering a version of its flagship XPS 13 laptop, plus a pair of laptops in each of its workhorse Inspiron and Latitude families. HP has a consumer OmniBook and a business-class EliteBook and has taken the opportunity to overhaul its entire laptop lineup to boot. Acer has the Swift 14 AI; Asus has the Vivobook S 15; Samsung has the Galaxy Book4 Edge.

For comparison, a total of four non-Surface devices launched with the first wave of Windows RT, and Samsung’s didn’t even launch in the US. By the spring of 2013, Acer’s CEO was saying that there was “no value” to Windows RT. Qualcomm had a grand total of three launch partners for the first wave of Snapdragon 835 PCs to launch with Windows 10 in late 2017. Each of those companies launched a single laptop apiece (anyone who bought those systems would be hosed four years later by Windows 11’s supported processor list, which didn’t support the 835).

Qualcomm

It could be that all of these companies’ enthusiasm is actually for the “Copilot+ PC” label, which denotes a Windows PC with a neural processing unit (NPU) fast enough to power Recall snapshots and other so-called “Next Generation experiences.” Everyone is trying to cash in on the AI boom, and at least for the next few months, these Arm-based Snapdragon PCs are the only ones that are going to be able to earn that label while Intel and AMD play catch-up. The upside of tying the two together is that Windows-on-Arm could rise along with Copilot+ if it succeeds; the risk is that consumer disinterest in either Copilot+ or the Snapdragon chips could drag down both initiatives.

But whatever the reason, a big wave of hardware from all the PC OEMs is another thing that makes this particular Arm Windows push feel different from the ones before. The others, as we have written elsewhere, have better app compatibility, a larger selection of native apps, and chips that claim to be unambiguously better than what Intel and AMD are doing, though we’ll need to do more testing before we know whether the expected performance and battery life improvements pan out in real life.

In the past, you sort of had to go out of your way to find and buy a Windows PC that happened to have an Arm chip in it, and you would probably notice that it didn’t do some of the same things as a “normal” PC. This wave of Arm announcements is a preview of what the future of Windows might look like—a broad mix of hardware using multiple chips and multiple instruction sets from multiple companies, but with all of that essentially hidden from most users by a familiar operating system and apps.