Bussiness

Osgood Perkins Gets Into the Family Business

“I don’t like upsetting anybody,” says Osgood Perkins, who’s earning a reputation for stylish, unsettling, and semi-autobiographical horror movies, “but I think horror presents the best opportunity for the full range of imagination.”

Photo: Courtesy of Osgood Perkins

The Hollywood Forever Cemetery may sound like an atmospheric location for a stroll with the industry’s most in-demand horror director, but in practice, the place is dishearteningly bucolic. When I meet up with Osgood Perkins there on a warm July afternoon, the sky is clear, the grass is eye-poppingly verdant, and peacocks roam the grounds, letting out occasional bellows. The cemetery is an oasis of manicured serenity on a bedraggled stretch of Santa Monica Boulevard, and while it’s still an active burial ground, it’s also a music venue, an outdoor movie theater, and, because of the number of celebrities interred there, a sightseeing destination. Vibes-wise, it’s as far from the gloomy Pacific Northwest setting of Longlegs, Perkins’s new film starring Maika Monroe as an FBI agent pursuing a serial killer (played by an indescribably upsetting Nicolas Cage), as you can get. None of this stops a trio of goth girls from conducting a DIY photo shoot near the entrance, bright Los Angeles sun be damned.

It isn’t until we’re ambling past Mickey Rooney’s crypt, which is, like many of the gravesites, adorned with a picture of its resident, that it occurs to me there are other reasons why Hollywood Forever Cemetery might feel like a ghoulish meeting place to Perkins. While his father, Psycho star Anthony Perkins, isn’t buried at Hollywood Forever, it would make sense for the child of a screen legend to have a more complicated relationship with a site that advertises its perpetual grip on public figures in its name. But when I bring it up, he waves my concerns away. “Please — it’s kitschy! Isn’t it kitschy?” Perkins mentions bringing his son to the similarly starry Pierce Brothers Memorial Park in Westwood to kill time while his wife was at an appointment nearby. “We were walking through with a ball, and I was playing with him. I looked down and realized I was standing on John Cassavetes. I was like, ‘Hey, bud.’” Perkins has arrived at a place of equanimity about death that belies the slow-simmering, obliquely personal nightmares he’s spent the last decade turning out for the big screen.

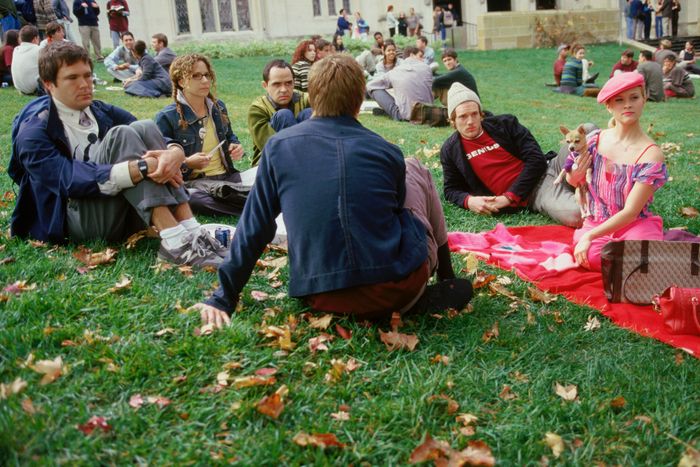

Perkins is 50, and tall, and dresses in layers like someone who’s been spending the last year-plus in Vancouver shooting three features back-to-back rather than an L.A. native. He’s disarmingly frank as we walk through graves — admitting to finding Christopher Nolan’s work boring, sharing a story about Jordan Peele telling him that the downside of being given the budget and freedom to make something like Nope is that then “it has to be the best fucking movie ever made.” He has a square-jawed handsomeness that would be noteworthy anywhere but in the movie industry, where it’s just the bar to entry. When he was making a go at being an actor in the early 2000s, his biggest role was one of comic relief. He was in Legally Blonde, not as Elle Woods’s love interest but as her stiff-necked classmate “Dorky” David Kidney — so memorably awkward that Elle has to give his romantic prospects a boost by pretending that he jilted her after a night of passion. Perkins just made a movie featuring a reigning scream queen, an iconic wild man, and enough sickening dread about evil seeping into the everyday to make it the fright phenomenon of the summer, but to some viewers, he’ll always be best known for that part in a chipper Reese Witherspoon rom-com. “It cut a wide swath, and it’s a good movie,” he says. “People recognize me for that at least five times a week.”

Osgood Perkins as Dorky Dave (left) in Legally Blonde.

Photo: MGM/Everett Collection

Perkins’s onscreen career technically began at the age of 6, when he was enlisted to play young Norman Bates in flashbacks in Psycho II. His memories of the experience are fuzzy, but he recalls being afraid to be there because “the set felt real to me … it was obviously scary.” That childhood gig was just for fun, a way to accompany his dad to work, but when he did drift into acting later, he appeared in small roles in Secretary and Not Another Teen Movie, with Legally Blonde being his peak. “Coming out of it afterwards, as an adult, I never believed myself as an actor,” he says. Instead, it’s the hours he spent ingesting music videos on MTV in the company of his musician brother Elvis, then futzing around with his friends and a camcorder as a teen, that he sees as more formative. When Perkins, after selling a few screenplays, made his directorial debut with A24’s The Blackcoat’s Daughter in 2015, his brother would compose the score.

An undertaker’s knot of a film involving a possible demonic possession or mental breakdown at a snowy Catholic boarding school in upstate New York, The Blackcoat’s Daughter wasn’t a hit for the then-fledgling distributor that picked it up. But it attracted attention from discerning genre fans for its cunningly fragmented timeline, which teased the nature of the relationship between a terrific Kiernan Shipka as a tormented schoolgirl and Emma Roberts, in a separate story thread, as an escapee from a mental hospital. Horror fans love to bicker over “elevated horror,” the label given to films like The Babadook, Hereditary, and It Follows to describe their art-house sensibilities and, according to detractors, to denigrate mainstream entries in the genre. The Blackcoat’s Daughter both did and didn’t fit into this subset. It was elegantly made, something that has held true for all of Perkins’s films, with a deliberate build and an unsettling use of negative space in its shots of a school emptied out for winter break. But while it played like a shriek of sublimated grief, its terrors weren’t metaphors for something else — they existed on their own terms.

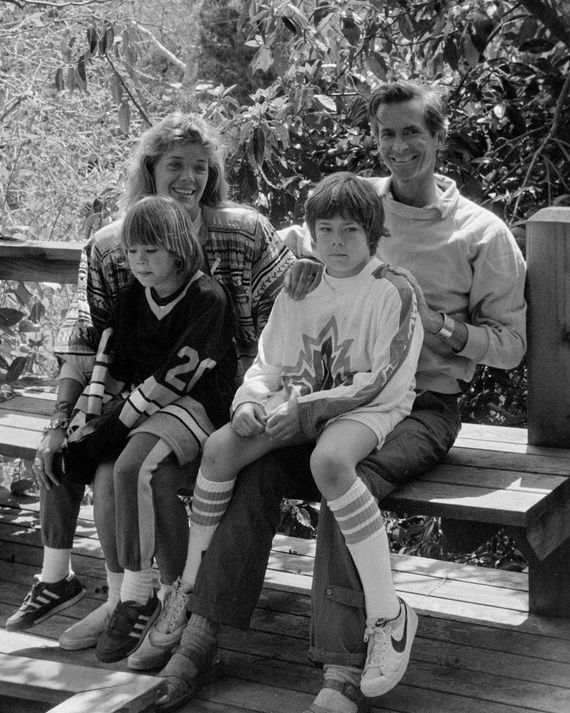

The Perkins family.

Photo: Jacky Coolen/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images

Every interview with Perkins contains a summary of his family history that serves as a concentrated dose of near-operatic tragedy. His father, Anthony, died from AIDS-related pneumonia in 1992 and had only been involved with men until undergoing conversion therapy and marrying Berry Berenson at the age of 41. Berenson, a photographer, actor, and model who was the granddaughter of designer Elsa Schiaparelli and who remained married to Anthony until his passing, died on September 11, having been a passenger on American Airlines Flight 11. It’s not surprising to learn that Perkins regards his horror filmography as a kind of indirect autobiography. His second feature, the haunted-house film I Am the Pretty Thing That Lives in the House, was dedicated to his father. It starred Ruth Wilson as a live-in aide who moves into the remote home of an author with dementia, and whose efforts to piece together what actually happened there in the past can be read as an excavation into the nature of someone who’s no longer around.

Longlegs, on the other hand, is about Perkins’s mother. “Mothers can craft stories,” he says as we loop along a lake and he looks toward the looming Cathedral Mausoleum, home to the remains of Peter Lorre and Rudolph Valentino. (For all his dry affect and working-director gear, with scruff and a baseball cap, Perkins still gives the occasional gleam of matinee-idol drama.) “They can tell their kids a version of what’s going on in their life or in the lives of their parents. And it’s done compassionately, protectively. And it’s not great.” In Longlegs, Agent Lee Harker (Monroe) gets assigned to investigate a series of murders with supernatural implications that are revealed to have a connection to details she never understood about her own childhood. In the character of Lee’s mother, Ruth (Alicia Witt), who raised her daughter alone and whose religiousness contains an off-key note, Perkins sees something personal about the domestic mythology his own mother wove. “My father was a homosexual man, or at least a bisexual man, who had a life that wasn’t reconcilable with his family life. For us, growing up, we just weren’t given that language. We weren’t given that access. Instead, there was a narrative put on things about what the family was like and how we were together and how my dad was. The challenge of rectifying what I felt I understood and what I was being told is the genesis for the mother that chooses to be complicit in a story.”

Osgood Perkins’s horror films Longlegs and The Blackcoat’s Daughter. From left: Photo: NeonPhoto: Petr Maur/A24/Everett Collection

Osgood Perkins’s horror films Longlegs and The Blackcoat’s Daughter. From top: Photo: NeonPhoto: Petr Maur/A24/Everett Collection

Longlegs is Perkins’s fourth film as a director — after I Am the Pretty Thing That Lives in the House, he directed Gretel & Hansel, a dark take on the fairy tale, from a screenplay by Rob Hayes for United Artists. It is, by design, his most accessible to date, a sleep-ruiningly creepy affair that starts off in the vein of Silence of the Lambs, then reveals itself to be something weirder and more warped. The film taps into multiple sources of American dread over the decades, from the Zodiac killer to the Satanic panic, while offering up one hell of a bogeyman courtesy of Cage, whose full appearance was cannily withheld from press materials but who bursts onscreen early in the film in a jolting opening sequence. If Longlegs manages to capitalize on the buzz it’s been accruing, it could mark the start of a major run for Perkins, who already has two more features in the can, with A24 rival Neon onboard to distribute both. One of them is Keeper, a single-location thriller starring Tatiana Maslany that he will only sum up as “grown-ups horror in a house.” The other is The Monkey, in which Maslany will also appear, and which has been slated for a release in February. An adaptation of the 1980 Stephen King short story about a cursed toy that causes people to die, it’s both the biggest thing Perkins has directed to date, with a budget in the $10–$11 million range, and the most autobiographical.

Osgood Perkins on the set of Longlegs.

Photo: Neon

As we take a break from the sun at a marble table so low that when we sit, our knees are around our ears, Perkins tells me that when he was first approached about The Monkey, there was a script attached that he “found really dopey.” “It was so about trauma. It was about a character who has had a trauma. And it was so phony to me.” He started to think, as he always does when writing, about taking the story away from the genericizing of experience and looking for the emotional truth he could apply from his own life. “What was true for me is the very literal thing that both my parents died in fucking crazy ways.” Where I Am the Pretty Thing That Lives in the House is about his father, and Longlegs about his mother, The Monkey is about him and his brother. It’s not a direct analogy — the siblings in the movie are twins, unlike Oz and Elvis, and they’re both played by Theo James in your typical Hollywood glow-up. But The Monkey is about struggling with how to cope with the loss of a parent, and it happens to be — and this feels key to understanding Perkins — a comedy. “That everybody, including yourself, dies is such an absurd thing. Even for people like me, who’ve been through death plenty, the notion that we all die is still fucking nuts. But what are you going to do about it? Not get out of bed?”

The Monkey will be R-rated, but Perkins has been thinking about it as the kind of movie you see too early as a kid — the way he saw The Amityville Horror and Salem’s Lot on the TV with his babysitter. Childhood’s a hugely impressionable time, even when you’re not being brought on the set of Psycho II to re-create the abusive early years of a murderous character played as an adult by your own father. Perkins has been considering that from the side of a parent now, especially since he gave his own teenage daughter small parts in Longlegs and The Monkey, more as a shared activity than a way of introducing her to acting. “I think for her, there’s a certain normalcy to it that I also felt, which is that some people’s dads are mechanics, some people’s dads are stockbrokers, and some people’s dads direct movies,” he says. “As my daughter would say, it’s not that deep.” He’s even been dabbling in acting again himself, turning up in bit parts in Nope and in the episode of the Peele-produced reboot of The Twilight Zone that Perkins directed. He’s at home in the genre, and while his next movie doesn’t have to be horror, he thinks it probably will be. “I don’t like upsetting anybody,” he says, “but I think horror presents the best opportunity for the full range of imagination,” containing “everything that we don’t understand, everything that we can’t see, everything that we don’t know, everything that lies beyond.”

We pry ourselves off the low marble stools and walk over to the grave of Maila Nurmi, better known as Vampira, a pioneering horror-movie host in the ’50s who also starred in Ed Wood’s Plan 9 From Outer Space. Someone’s left what looks like fan art featuring the character on her tombstone, which is low to the ground and modest by Mickey Rooney standards but is nevertheless emblazoned with a sketch of Nurmi in her signature black mermaid dress. Perkins props it up next to her name and smiles. “She was a friend of my dad’s, early on in Hollywood,” he says. “And I just think this sort of sexy-horror kitsch is really great. It’s a happy coagulating of different ideas.”